- Sampling (music)

-

This article is about reusing existing sound recordings in creating new works. For other uses, see Sample (disambiguation).

In music, sampling is the act of taking a portion, or sample, of one sound recording and reusing it as an instrument or a different sound recording of a song or piece. Sampling was originally developed by experimental musicians working with musique concrète and electroacoustic music, who physically manipulated tape loops or vinyl records on a phonograph. In the late 1960s, the use of tape loop sampling influenced the development of minimalist music and the production of psychedelic rock and jazz fusion. In the 1970s, DJs who experimented with manipulating vinyl on two turntables gave birth to hip hop music, the first popular music genre based originally around the art of sampling. The widespread use of sampling in popular music increased with the rise of electronic music and disco in the mid 1970s to early 1980s, the development of electronic dance music and industrial music in the 1980s, and the worldwide influence of hip hop since the 1980s on genres ranging from contemporary R&B to indie rock. Since that time sampling is often done with a sampler, originally a piece of hardware, but today, more commonly a computer program. Vinyl emulation software may also be used, however, and many turntablists continue to sample using traditional methods. The inclusion of sampling tools in modern digital production methods increasingly introduced sampling into many genres of popular music, as well as genres predating the invention of sampling, such as classical music, jazz and various forms of traditional music.

Often "samples" consist of one part of a song, such as a rhythm break, which is then used to construct the beat for another song. For instance, hip hop music developed from DJs repeating the breaks from songs to enable continuous dancing.[1] The Funky drummer break and the Amen break, both brief fragments taken from soul and funk music recordings of the 1960s, have been among the most common samples used in dance music and hip hop of recent decades, with some entire subgenres like breakbeat being based largely on complex permutations of a single one of these samples. Samples from rock recordings have also been the basis of new songs; for example, the drum introduction from Led Zeppelin's "When the Levee Breaks" was sampled by the Beastie Boys, Dr. Dre, Eminem, Mike Oldfield, Rob Dougan, Coldcut, Depeche Mode, Erasure and Nine Inch Nails, among others. Often, samples are not taken from other music, but from spoken words, including those in non-musical media such as movies, TV shows and advertising. Sampling does not necessarily mean using pre-existing recordings. A number of composers and musicians have constructed pieces or songs by sampling field recordings they made themselves, and others have sampled their own original recordings. The musicians in the trip hop band Portishead, for example, made some use of existing samples, but also scratched, manipulated and sampled musical parts they themselves had originally played in order to construct their songs.

The use of sampling is controversial legally and musically. Experimental musicians who pioneered the technique in the 1940s to the 1960s sometimes did not inform or receive permission from the subjects of their field recordings or from copyright owners before constructing a musical piece out of these samples. In the 1970s, when hip hop was confined to local dance parties, it was unnecessary to obtain copyright clearance in order to sample recorded music at these parties. As the genre became a recorded form centred around rapping in the 1980s and subsequently went mainstream, it became necessary to pay to obtain legal clearance for samples, which was difficult for all but the most successful DJs, producers and rappers. As a result, a number of recording artists ran into legal trouble for uncredited samples, while the restrictiveness of current US copyright laws and their global impact on creativity also came under increased scrutiny. The hip hop genre also shifted toward a wider aesthetic in which sampling was only one method of constructing beats, with many producers instead crafting wholly original recordings to serve as backing tracks. Aside from legal issues, sampling has been both championed and criticized. Hip hop DJs today take different approaches to sampling, with some critical of its obvious use. Some critics, particularly those with a rockist outlook, have expressed the belief all sampling is lacking in creativity, while others say sampling has been innovative and revolutionary. Those whose own work has been sampled have also voiced a wide variety of opinions about the practice, both for and against sampling.

Contents

Types

Once recorded, samples can be edited, played back, or looped (i.e. played back continuously). Types of samples include:

Loops

Main article: Music loopHow To Make A Sampled beat

The drums and percussion parts of many modern recordings are really a variety of short samples of beats strung together. Many libraries of such beats exist and are licensed so that the user incorporating the samples can distribute their recording without paying royalties. Such libraries can be loaded into samplers. Though percussion is a typical application of looping, many kinds of samples can be looped. A piece of music may have an ostinato which is created by sampling a phrase played on any kind of instrument. There is software which specializes in creating loops.

Musical instruments

Whereas loops are usually a phrase played on a musical instrument, this type of sample is usually a single note. Music workstations and samplers use samples of musical instruments as the basis of their own sounds, and are capable of playing a sample back at any pitch. Many modern synthesizers and drum machines also use samples as the basis of their sounds. (See sample-based synthesis for more information.) Most such samples are created in professional recording studios using world-class instruments played by accomplished musicians. These are usually developed by the manufacturer of the instrument or by a subcontractor who specializes in creating such samples. There are businesses and individuals who create libraries of samples of musical instruments. Of course, a sampler allows anyone to create such samples.

Possibly the earliest equipment used to sample recorded instrument sounds are the Chamberlin, which was developed in the 1940s, and its better-known cousin, the Mellotron, marketed in England in the 1960s. Both are tape replay keyboards, in which each key pressed triggers a prerecorded tape loop of a single note.

Musicians can reproduce the same samples of break beats like the "Amen" break which was composed, produced and mastered by the Winston Brothers in 1960s. Producers in the early 1990s have used the whole 5.66 second sample; but music workstations like the Korg Electribe Series (EM-1, ES-1; EMX-1 and the ESX-1) have used the "Amen" kick, hi hat and snare in their sound wave libraries for free use. Sampler production companies have managed to use these samples for pitch, attack and decay and DSP effects to each drum sound. These features allow producers to manipulate samples to match other parts of the composition.

Most sample sets consist of multiple samples at different pitches. These are combined into keymaps, that associate each sample with a particular pitch or pitch range. Often, these sample maps may have different layers as well, so that different velocities can trigger a different sample.

Samples used in musical instruments sometimes have a looped component. An instrument with indefinite sustain, such as a pipe organ, does not need to be represented by a very long sample because the sustained portion of the timbre is looped. The sampler (or other sample playback instrument) plays the attack and decay portion of the sample followed by the looped sustain portion for as long as the note is held, then plays the release portion of the sample.

Resampled layers of sounds generated by a music workstation

To conserve polyphony, a workstation may allow the user to sample a layer of sounds (piano, strings, and voices, for example) so they can be played together as one sound instead of three. This leaves more of the instruments' resources available to generate additional sounds.

Recordings and popular examples

There are several genres of music in which it is commonplace for an artist to sample a phrase of a well-known recording and use it as an element in a new composition. A well-known example includes the sample of Queen/David Bowie's "Under Pressure" (1981) in Vanilla Ice's "Ice Ice Baby" (1990). Some of the earliest examples in popular electronic music were from Yellow Magic Orchestra,[2][3] such as "Computer Game / Firecracker" (1978) sampling a Martin Denny melody[4] and Space Invaders[5] game sounds,[4] while Technodelic (1981) was one of the first albums to feature mostly samples and loops.[3]

On MC Hammer's album Please Hammer, Don't Hurt 'Em, the successful single "U Can't Touch This" sampled Rick James' 1981 "Super Freak". "Have You Seen Her" was a cover of the Chi-Lites and "Pray" sampled Prince's "When Doves Cry" as well as Faith No More's "We Care a Lot".[6] "Dancin' Machine" sampled The Jackson 5, "Help the Children" interpolates Marvin Gaye's "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)", and "She's Soft and Wet" also sampled Prince's "Soft and Wet".[7] Hammer's previous album and future albums would continue to sample music, although not as notable as this album did.

The Isley Brothers' song Between The Sheets is a song heavily sampled by many different artists, most notably Notorious BIG's Big Poppa, and Gwen Stefani's Luxurious.

In many cases, artists even join the original artist or receive permission to sample songs such as Coolio did for "Gangsta's Paradise". It sampled the chorus and music of the song "Pastime Paradise" by Stevie Wonder (1976). Wonder performed the song with Coolio and L.V. at the 1995 Billboard Awards. Notably, much of Coolio's album excessively sampled other artists; including "Too Hot" (contains an interpolation of "Too Hot", originally performed by Kool & The Gang), Cruisin'" (contains an interpolation of "Cruisin'", originally performed by Smokey Robinson & the Miracles), "Sumpin' New" (which contains samples of both "Thighs High (Grip Your Hips More)" performed by Tom Browne and "Wikka Wrap" performed by The Evasions), "Smilin'" (contains an interpolation of "You Caught Me Smiling", originally performed by Sly & The Family Stone), "Kinda High, Kinda Drunk" (contains interpolations of "Saturday Night" and "The Boyz in Da Hood"), "For My Sistas" (contains an interpolation of "Make Me Say It Again Girl", originally performed by The Isley Brothers), "A Thing Goin' On" (contains an interpolation of "Me & Mrs. Jones"), "The Revolution" (contains an interpolation of "Magic Night"), "Get Up, Get Down" (contains an interpolation of "Chameleon", originally performed by Herbie Hancock),[8] and the first line of "Gangster's Paradise" is taken from Psalm 23.[9]

Another example is in 1997, when Sean Combs collaborated with Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin on the song "Come with Me" for the Godzilla film. The track sampled the Led Zeppelin song "Kashmir" (approved by Jimmy Page). "I'll Be Missing You" sampled the melody and some of the lyrics from The Police's "Every Breath You Take" from 1983. The single also borrows the melody from the well-known American spiritual "I'll Fly Away." Combs went on to perform it with Sting and Faith Evans on the MTV Video Music Awards. By the late 1990s, "Puffy" was receiving criticism for watering down and overly commercializing hip-hop and overusing guest appearances by other artists, samples and interpolations of past hits in his own hit songs.[10][11] The Onion parodied this phenomenon in a 1997 article called "New rap song samples "Billie Jean" in its entirety, adds nothing."[12]

Artists can often sample their own songs in other songs they have recorded, often in differently-titled remixes. The Chemical Brothers sampled their own song "The Sunshine Underground" in their later song "We Are the Night".

Sampler

Main article: Sampler (musical instrument)Legal issues

Sampling has been an area of contention from a legal perspective. Early sampling artists simply used portions of other artists' recordings, without permission; once rap and other music incorporating samples began to make significant money, the original artists began to take legal action, claiming copyright infringement. Some sampling artists fought back, claiming their samples were fair use (a legal doctrine in the USA that is not universal). International sampling is governed by agreements such as the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and the WIPO Copyright and Performances and Phonograms Treaties Implementation Act.

Early cases

Sampling existing (copyrighted) recordings using manipulation with tape recorders goes back at least as far as 1961, when James Tenney created Collage #1 ("Blue Suede") from samples of Elvis Presley's recording of the song "Blue Suede Shoes." At the time, many artists such as Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs were experimenting with the new technology that was tape-recording by manipulating existing works such as radio broadcasts. Brion Gysin's work tended to favor his permutation poems as the vehicle for cut-ups with spliced repetition of the same series of words rearranged in every conceivable pattern, frequently utilizing snippets of speeches or news broadcasts. Burroughs preferred a much more frantic and disorganized sound that would later spawn similar disjointed collage material from modern groups such as Negativland. Burroughs would record, for instance, a radio broadcast about military action, then dub parts of the broadcast likely at random often stuttering and distorting the original work far beyond comprehension.

However, before then, the 1956 novelty hit single "The Flying Saucer", by Buchanan and Goodman, used segments of the original recordings of 18 different chart hits from 1955–56, intertwined with spoken "news" commentary in the style of Orson Welles' "War of the Worlds" radio broadcast, to tell the story of a visit from a flying saucer. After the record was issued, an agreement was reached with music publishing houses for them to take a share of royalties from the records sold. Although his partnership with Buchanan soon ended, Dickie Goodman continued to make similar records through the 1960s and 1970s, one of his biggest hits being "Mr. Jaws" in 1975.[13][14]

Simon and Garfunkel sampled themselves in using a portion of their song "The Sounds of Silence" in "Save the life of my child" from their 1967 "Bookends" album. The Beatles also used the technique on a number of popular recordings in the mid to late '60s, including "Yellow Submarine", "Revolution 9" and "I Am the Walrus." John Kongos is credited in the Guinness World Records as the first person to sample a song with his single, "He's Gonna Step On You Again". Timothy Leary sampled the Beatles and the Rolling Stones among others on his album You Can Be Anyone This Time Around in 1970.

In the early 1970s, DJ Kool Herc often looped hard funk break beats at block parties in The Bronx. However, sampling did not truly take off in popular music until the early eighties when pioneering hip hop producers, such as Grandmaster Flash, started to produce rap records using sampled breaks rather than live studio bands, which had until then been the norm.

Conventional wisdom would hold that the first popular rap single to feature sampling was "Rapper's Delight" by The Sugarhill Gang on their own independent Sugar Hill Label in 1979. However, instead of 'sampling' the existing record "Good Times" by Chic, Sugar Hill employed a house band, called "Positive Force" to record a copy of "Good Times" which was then rapped over. Doug Wimbish and other session musicians were called upon to play live music on many classic Sugar Hill records. Those sounds are not samples but live musicians.

Earliest examples of this practice include Grandmaster Flash's - "The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel" (1981) (which was made by recording vinyl manipulation on a pair of turntables and used the "Apache" break by the Incredible Bongo Bong Band amongst other famous breaks), Brother D and the Collective Effort's "How We Gonna Make The Black Nation Rise" (1984) (which sampled the beat and bass line from Cheryl Lynn's 1978 hit "Got to be Real") and UTFO's "Roxanne Roxanne" (1984). Bill Holt's Dreamies (1974) is often cited as one of the earliest examples of sampling in popular music. Later examples of sampling include Big Audio Dynamite and their 1985 album This Is Big Audio Dynamite and the single E=MC² which Mick Jones (formerly of The Clash) sampled snippets of audio from various films including works by Nicolas Roeg which make up the Roeg homage E=MC². The 1981 album by David Byrne and Brian Eno, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, used sampling extensively for the songs' vocals.

One of the first major legal cases regarding sampling was with UK dance act M|A|R|R|S "Pump Up the Volume". As the record reached the UK top ten, producers Stock Aitken Waterman obtained an injunction against the record due to the unauthorized use of a sample from their hit single "Roadblock". The dispute was settled out of court, with the injunction being lifted in return for an undertaking that overseas releases would not contain the "Roadblock" sample, and the disc went on to top the UK singles chart. The sample in question had been so distorted as to be virtually unrecognizable, and SAW didn't realize their record had been used until they heard co-producer Dave Dorrell mention it in a radio interview.

In 1987, The JAMs released 1987 (What The Fuck Is Going On?) 1987 was produced using extensive unauthorised samples which plagiarised a wide range of musical works. They were ordered by the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society to destroy all unsold copies of the album because of the numerous uncleared samples, after a complaint from ABBA. In response, The JAMs disposed of many copies of 1987 in unorthodox, publicised ways. They also released a version of the album titled "1987 (The JAMs 45 Edits)", stripped of all unauthorised samples to leave periods of protracted silence and so little audible content that it was formally classed as a 12-inch single.

2 Live Crew, a hip-hop group familiar with controversy, was often in the spotlight for their 'obscene' and sexually explicit lyrics. They sparked many debates about censorship in the music industry. However, it was their 1989 album As Clean as They Wanna Be (a re-tooling of As Nasty As They Wanna Be) that began the prolonged legal debate over sampling. The album contained a track entitled "Pretty Woman," based on the well-known Roy Orbison song Oh, Pretty Woman. 2 Live Crew's version sampled the guitar, bass, and drums from the original, without permission. While the opening lines are the same, the two songs split ways immediately following.[15]

For example:

Roy Orbison's version – "Pretty woman, walking down the street/ Pretty woman, the kind I'd like to meet."

2 Live Crew's version – "Big hairy woman, all that hair ain't legit,/ Cause you look like Cousin Itt."[16]In addition to this, while the music is identifiable as the Orbison song, there were changes implemented by the group. The new version contained interposed scraper notes, overlays of solos in different keys, and an altered drum beat.[16]

The group was sued by the song's copyright owners Acuff-Rose. The company claimed that 2 Live Crew's unauthorized use of the samples devalued the original, and was thus a case of copyright infringement. The group claimed they were protected under the fair use doctrine. The case of Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music came to the Supreme Court in 1994.

In reviewing the case, the Supreme Court didn't consider previous ruling in which any commercial use (and economic gain) was considered copyright infringement. Instead they re-evaluated the original frame of copyright as set forth in the Constitution. The opinion that resulted from Emerson v. Davies played a major role in the decision.[15]

"[In] truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before." Emerson v. Davies,8 F.Cas. 615, 619 (No. 4,436) (CCD Mass. 1845)[16]

Perhaps what played a larger role was the result from the Folsom v. Marsh case:

"look to the nature and objects of the selections made, the quantity and value of the materials used, and the degree in which the use may prejudice the sale, or diminish the profits, or supersede the objects, of the original work." Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F.Cas. 342, 348 (No. 4,901) (CCD Mass. 1841)[16]

The court ruled that any financial gain 2 Live Crew received from their version did not infringe upon Acuff-Rose because the two songs were targeted at very different audiences. 2 Live Crew's use of copyrighted material was protected under the fair use doctrine, as a parody, even though it was released commercially.[15] While the appellate court had determined that the mere nature of the parody made it inherently unfair, the Supreme Court's ruling reversed this decision, with Justice David Souter writing that the lower court was wrong in determining parody alone to be a sufficient criterion for copyright infringement.[17]

1990s

Rick James sued MC Hammer for infringement of copyright on the track "U Can't Touch This" (which sampled his 1981 song "Super Freak"), but the suit was settled out of court when Hammer agreed to credit James as co-composer, effectively cutting James in on the millions of dollars the record was earning. Hammer was also sued by Felton Pilate (who had worked with the successful vocal group Con Funk Shun) and by several of his former backers, and faced charges that performance troupe members endured an abusive, militaristic atmosphere.[18]

In 1992, Hammer also admitted in depositions and court documents to getting the idea for the song "Here Comes The Hammer" from a Christian recording artist in Dallas, Texas named Kevin Christian. Christian had filed a 16 million dollar lawsuit against Hammer for copyright infringement for his song entitled "Oh-Oh, You Got The Shing". This fact compounded with witness testimony from both Hammer's and Christian's entourages and other evidence including photos brought about a settlement with Capitol Records in 1994. The terms of the settlement remain sealed. Hammer settled with Christian the following year.[19][20]

In the early 1990s, Vanilla Ice sampled the bassline of the 1981 song "Under Pressure" by Queen and David Bowie for his 1990 single "Ice Ice Baby".[21] Freddie Mercury and David Bowie did not receive credit or royalties for the sample.[22] In a 1990 interview, Rob Van Winkle said the two melodies were slightly different because he had added an additional note. In later interviews, Van Winkle readily admitted he sampled the song and claimed his 1990 statement was a joke; others, however, suggested he had been serious.[23][24] Van Winkle later paid Mercury and Bowie, who have since been given songwriting credit for the sample.[23]

More dramatically, Biz Markie's album I Need a Haircut was withdrawn in 1992 following a US federal court ruling,[25] that his use of a sample from Gilbert O'Sullivan's "Alone Again (Naturally)" was willful infringement. This case had a powerful effect on the record industry, with record companies becoming very much concerned with the legalities of sampling, and demanding that artists make full declarations of all samples used in their work. On the other hand, the ruling also made it more attractive to artists and record labels to allow others to sample their work, knowing that they would be paid—often handsomely—for their contribution.

A notable case in the early 1990s involved the dispute between the group Negativland and Casey Kasem over the band's use of un-aired vocal snippets from Kasem's radio program American Top 40 on the Negativland single "U2".

Another notable case involved British dance music act Shut Up And Dance. Shut Up And Dance were a fairly successful Breakbeat Hardcore and rave scene outfit who like their contemporaries had liberally used samples in the creation of their music - without clearance from the individuals concerned. Although frowned upon the British music industry usually turned a blind eye to this mainly underground scene, however with rave at its commercial peak in the UK, Shut Up And Dance released the single "Raving I'm Raving" an upbeat breakbeat hardcore record which shot to #2 on the UK Singles Chart in May 1992. At the core of "Raving" were significant samples of Marc Cohn's hit single "Walking in Memphis" with some of the lyrical content changed and sung by Peter Bouncer. Shut Up And Dance hadn't sought clearance from Marc Cohn for the samples they used in "Raving" and Marc Cohn took legal action against Shut Up And Dance for breach of copyright. An out of court settlement was eventually reached between Shut Up And Dance and Cohn which saw "Raving" in its current form banned and the proceeds from the single given to charity. Ironically Shut Up and Dance were later commissioned to produce remixes for Cher's 1995 cover version of "Walking In Memphis" and were allowed by Cohn to use parts from the deleted "Raving I'm Raving" for this remix. Undeterred from earlier sampling issues they then went on to have relatively good success in the UK with a cover of Duran Duran's "Save A Prayer", entitled "Save it til the mourning after" reaching No. 25 in the UK Singles Chart in 1995.

The Shut Up And Dance case had major ramifications on the use of samples in the UK and most artists and record labels now seek clearance for samples they use. However there are still cases which involve UK artists using uncleared samples. In October 1996 The Chemical Brothers released the single Setting Sun inspired by The Beatles' Tomorrow Never Knows and featuring Oasis' Noel Gallagher on vocals - a long admirer of The Beatles' work. Setting Sun hit #1 on the UK Singles Chart on first week of release and the common consensus was The Chemical Brothers had sampled/looped significant parts of Tomorrow Never Knows in the creation of Setting Sun. The three remaining Beatles took legal action against The Chemical Brothers/Virgin Records for breach of copyright, however a musicologist proved The Chemical Brothers had independently created Setting Sun - albeit in a similar vein to Tomorrow Never Knows.

In 1997 The Verve was forced to pay 100% of their royalties from their hit "Bitter Sweet Symphony" for the use of a licensed sample from an orchestral cover version of The Rolling Stones' hit "The Last Time".[26] The Rolling Stones' catalogue is one of the most litigiously protected in the world of popular music—to some extent the case mirrored the legal difficulties encountered by Carter the Unstoppable Sex Machine when they quoted from the song "Ruby Tuesday" in their song "After the Watershed" some years earlier. In both cases, the issue at stake was not the use of the recording, but the use of the song itself—the section from "The Last Time" used by the Verve was not even part of the original composition, but because it derived from a cover version of it, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were still entitled to royalties and credit on the derivative work. This illustrates an important legal point: even if a sample is used legally, it may open the artist up to other problems.

2000s

In the summer of 2001, Mariah Carey released her first single from Glitter entitled "Loverboy" which featured a sample of "Firecracker" by Yellow Magic Orchestra. A month later, Jennifer Lopez released "I'm Real" with the same "Firecracker" sample. Carey quickly discarded it and replaced it with "Candy" by Cameo.

In 2001, Armen Boladian and his company Bridgeport Music Inc. filed over 500 copyright infringement suits against 800 artists using samples from George Clinton's catalogue.

Public Enemy recorded a track entitled "Psycho of Greed" (2002) for their album Revolverlution that contained a continuous looping sample from The Beatles' track "Tomorrow Never Knows". However, the clearance fee demanded by Capitol Records and the surviving Beatles was so high that the group decided to pull the track from the album.

Danger Mouse with the release of The Grey Album in 2004, which is a remix of The Beatles' self-titled album and rapper Jay-Z's The Black Album has been embroiled in a similar situation with the record label EMI issuing cease and desist orders over uncleared Beatles samples.

On March 19, 2006, a judge ordered that sales of The Notorious B.I.G.'s album Ready to Die be halted because the title track sampled a 1972 song by the Ohio Players, "Singing in the Morning", without permission.[27]

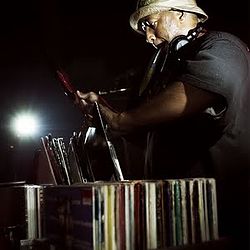

Girl Talk Producing Sample-Based Music Live

Girl Talk Producing Sample-Based Music Live

On November 20, 2008, electronic band Kraftwerk convinced the German Federal Supreme Court that even the smallest shreds of sounds ("Tonfetzen") are "copyrightable" (e.g. protected), and that sampling a few bars of a drum beat can be an infringement.[28]

Legal issues in practice

The most recent significant copyright case involving sampling held that even sampling three notes could constitute copyright infringement. Bridgeport Music Inc. v. Dimension Films, 410 F.3d 792 (6th Cir. 2005). This case was roundly criticised by many in the music industry, including the RIAA.

There has been a second important US case on music sampling involving the Beastie Boys who sampled the sound recording of a flute track by James Newton in their song "Pass the Mic." The Beastie Boys properly obtained a license to use the sound recording but did not clear the use of the song (the composition on which the recording is based including any music and lyrics). In Newton v. Diamond and Others 349 F.3d 591 (9th Cir. 2003) the US Appeals Court held that the use of the looped sample of a flute did not constitute copyright infringement as the core of the song itself had not been used.

A June 2006 case involving Ludacris and Kanye West held that their use of the phrases "like that" and "straight like that" which had been used on an earlier hip-hop track by another artist was not infringing use.

The New Orleans–based company Cash Money Records and former rapper Juvenile were taken to court by local performer DJ Jubilee (signed to Take Fo' Record Label) for using chants from his song titled Back That Ass Up. Both artist had used the same chant in each song, but Juvenile won the case because of the title's name change to Back That Azz Up, which sold 2 million copies. Because of the name change, Jubilee lacked evidence that Juvenile had stolen from him, and Jubilee could not earn Juvenile's income from his song.[citation needed]

Today, most mainstream acts obtain prior authorization to use samples, a process known as "clearing" (gaining permission to use the sample and, usually, paying an up-front fee and/or a cut of the royalties to the original artist). Independent bands, lacking the funds and legal assistance to clear samples, are at a disadvantage - unless they seek the services of a professional sample replay company or producer.

Recently, a movement — started mainly by Lawrence Lessig — of free culture has prompted many audio works to be licensed under a Creative Commons license that allows for legal sampling of the work provided the resulting work(s) are licensed under the same terms.

Spoken word

Usually taken from movies, television, or other non-musical media, spoken word samples are often used to create atmosphere, to set a mood, or even comic effect. The American composer Steve Reich used samples from interviews with Holocaust survivors as a source for the melodies on the 1988 album Different Trains, performed by the Kronos Quartet.

Many genres utilize sampling of spoken word to induce a mood, and Goa trance often employs samples of people speaking about the use of psychoactives, spirituality, or science fiction themes. Industrial is known for samples from horror/sci-fi movies, news broadcasts, propaganda reels, and speeches by political figures. The band Ministry frequently samples George W. Bush. Paul Hardcastle used recordings of a news reporter, as well as a soldier and ambient noise of a protest, in his single "Nineteen," a song about Vietnam war veterans and Posttraumatic stress disorder. The band Negativland samples from practically every form of popular media, ranging from infomercials to children's records. In the song "Civil War", Guns N' Roses samples from the 1967 film Cool Hand Luke, on the album Use Your Illusion II. Sludge band Dystopia make frequent use of samples, including news clips and recordings of junkies to create a bleak and nihilistic atmosphere. Other bands that frequently used samples in their work are noise rockers Steel Pole Bath Tub and death metal band Skinless.

Unconventional sounds

These are not musical in the conventional sense - that is, neither percussive nor melodic - but which are musically useful for their interesting timbres or emotional associations, in the spirit of musique concrète. Some common examples include sirens and klaxons, locomotive whistles, natural sounds such as whale song, and cooing babies. It is common in theatrical sound design to use this type of sampling to store sound effects that can then be triggered from a musical keyboard or other software. This is very useful for high precision or nonlinear requirements.

See also

- Amen Brother - one of the most sampled tracks of all time

- Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

- Compulsory Sampling License - would allow artists to freely sample without copyright owner's permission

- Cover version

- Hip hop production

- Interpolation

- mashup - extensive page illuminating current practices of extensive sampling and their precedents

- Musical montage - is a technique where sound objects or compositions are created from collage.

- Music loop

- Musique concrète - early development of fundamental importance in using recorded sound

- Plunderphonics - in which samples are the sole source of sound for new compositions

- Remix

- Sampler (musical instrument) - hardware and software platforms

- Sampling (signal processing) - Basic PCM theory

- Sound collage - production of new sound material using portions, or samples, of previously made recordings.

- WIPO Copyright and Performances and Phonograms Treaties Implementation Act

Sampling in other contexts

- Appropriation (art) - (Visual arts) often refers to the use of borrowed elements in the creation of new work.

- Collage - a work of visual arts made from an assemblage of different forms, thus creating a new whole.

- Cut-up technique - an aleatory literary technique or genre in which a writing is cut up at random and rearranged to create a new text.

- Found footage - a method of compiling films partly or entirely of footage which has not been created by the filmmaker.

- Papier collé - a painting technique and type of collage.

- Assemblage (composition) - a method for creating texts by explicitly using existing texts.

Footnotes

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2004). Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip Hop, p.36. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6696-9.

- ^ Mayumi Yoshida Barakan & Judith Connor Greer (1996). Tokyo city guide. Tuttle Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 0804819645. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vJbd43uxLiMC&pg=PA144. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ a b Carter, Monica (June 30 2011). "It’s Easy When You’re Big In Japan: Yellow Magic Orchestra at The Hollywood Bowl". The Vinyl District. http://www.thevinyldistrict.com/losangeles/2011/06/it%E2%80%99s-easy-when-you%E2%80%99re-big-in-japan-yellow-magic-orchestra-at-the-hollywood-bowl/. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ a b Lewis, John (4 July 2008). "Back to the future: Yellow Magic Orchestra helped usher in electronica - and they may just have invented hip-hop, too". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/jul/04/electronicmusic.filmandmusic11. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ "The Wire, Issues 221-226", The Wire: p. 44, 2002, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=qyFMAAAAYAAJ, retrieved 2011-05-25

- ^ (Posted: May 17, 1990) (1990-05-17). "MC Hammer: Please Hammer, Don't Hurt 'Em : Music Reviews". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. http://web.archive.org/web/20071121142132/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/mchammer/albums/album/214027/review/5943181/please_hammer_dont_hurt_em. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ Artist Search Results for "mc hammer" | WhoSampled

- ^ Dangerous Minds (1995) - IMDb

- ^ Coolio's Sample-Based Music | WhoSampled

- ^ Keith Farley. "Forever" – Overview. Allmusic: 1999.

- ^ Jason Birchmeier. "The Saga Continues" – Overview. Allmusic: 2001.

- ^ New Rap Song Samples 'Billie Jean' In Its Entirety, Adds Nothing. (September 1997) The Onion. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Greg Prato, Biography of Dickie Goodman, Allmusic.com

- ^ Chuck Miller, Dickie Goodman: We've Spotted The Shark Again, originally published in Goldmine magazine

- ^ a b c McLe_0385513259_7p_all_r1.qxd

- ^ a b c d 2Live Crew

- ^ Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music (1993)

- ^ MC Hammer: Biography from Answers.com

- ^ "Songwriter claims Hammer stole his song: sues him. (Muhammad Bilal Abdullah)". Jet. February 1, 1993. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-13360829.html.

- ^ Weitz, Matt (February 26, 1998). "Hammered". Dallas Observer. http://www.dallasobserver.com/1998-02-26/news/hammered/.

- ^ Hess, Mickey (2007). "Vanilla Ice: The Elvis of Rap". Is Hip Hop Dead?. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 118. ISBN 0275994619.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2000). "Legends of the Fall: Behind the Music". Science Fiction, Children's Literature, and Popular Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 100. ISBN 0313308470.

- ^ a b Stillman, Kevin (February 27, 2006). "Word to your mother". Iowa State Daily. http://www.iowastatedaily.com/news/article_766d27d2-dc56-5ff3-9040-47e44d46094f.html. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ^ Nick, Adams (2006). "When White Rappers Attack". Making Friends with Black People. Kensington Books. p. 75. ISBN 075821295X.

- ^ Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc., 780 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1991),

- ^ Superswell.com: "Horror Stories of Sampling"

- ^ Staff reporter (2006-03-18). "Judge halts Notorious B.I.G. album sales". USA Today. Associated Press. http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/news/2006-03-18-rap-sampling_x.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-24. "A judge halted sales of Notorious B.I.G.'s breakthrough 1994 album "Ready to Die" after a jury decided the title song used part of an Ohio Players tune without permission." (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5h1Fm1b0I)

- ^ http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1504982 Metall Auf Metall (Kraftwerk, et al. v. Moses Pelham, et al.) Decision of the German Federal Supreme Court No. I ZR 112/06 Dated November 20, 2008, at 56 Journal of the Copyright Society 1017 (2009)

Further reading

- Katz, Mark. "Music in 1s and 0s: The Art and Politics of Digital Sampling." In Capturing Sound: How Technology has Changed Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 137-57. ISBN 0-520-24380-3

- McKenna, Tyrone B. (2000) "Where Digital Music Technology and Law Collide - Contemporary Issues of Digital Sampling, Appropriation and Copyright Law" Journal of Information, Law & Technology. Available online at:

- http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/law/elj/jilt/2000_1/mckenna/?textOnly=true

- http://www.musiclawupdates.com/index_main.htm Challis, B (2003) The Song Remains The Same - A Review of the Legalities of Music Sampling

External links

- the-breaks AKA The (Rap) Sample FAQ, samples and their sources in all forms of music

- WhoSampled - a user-generated database of sampled music where all samples can be listened to side-by-side

- The Sample Clearance Fund: A proposal a 1998 article about an attempt to legalize sampling; predates Creative Commons Sampling licenses of several years

- SCORCCiO Sample Replays - Professional sample replay producers; samples recreated to accurately replace any uncleared sample usage.

- samplefaq.net - an interactive Hip Hop Sample community

Categories:- Sampling

- DJing

- Plagiarism controversies

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.