- New Deal

-

This article is about the 1930s economic programs of the United States. For other uses, see New Deal (disambiguation).

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was responsible for initiatives and programs collectively known as the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal.The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call the "3 Rs": Relief, Recovery, and Reform. That is, Relief for the unemployed and poor; Recovery of the economy to normal levels; and Reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat depression. The New Deal produced a political realignment, making the Democratic Party the majority (as well as the party which held the White House for seven out of nine Presidential terms from 1933 to 1969), with its base in liberal ideas, big city machines, and newly empowered labor unions, ethnic minorities, and the white South. The Republicans were split, either opposing the entire New Deal as an enemy of business and growth, or accepting some of it and promising to make it more efficient. The realignment crystallized into the New Deal Coalition that dominated most American elections into the 1960s, while the opposition Conservative Coalition largely controlled Congress from 1938 to 1964.

Historians distinguish a "First New Deal" (1933) and a "Second New Deal" (1934–36). Some programs were declared unconstitutional, and others were repealed during World War II. The "First New Deal" (1933) dealt with diverse groups, from banking and railroads to industry and farming, all of which demanded help for economic recovery. A "Second New Deal" in 1934–36 included the Wagner Act to promote labor unions, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) relief program, the Social Security Act, and new programs to aid tenant farmers and migrant workers. The final major items of New Deal legislation were the creation of the United States Housing Authority and Farm Security Administration, both in 1937, then the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which set maximum hours and minimum wages for most categories of workers[1] and the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938.

Despite Roosevelt campaigning heavily against anti-New Deal Republicans and anti-New Deal Democrats, Republicans gained many seats in Congress in the 1938 midterm elections and the Democrats opponents of the New Deal retained their seats,[2] resulting in the WPA, CCC and other relief programs being shut down during World War II by the Conservative Coalition (i.e., the opponents of the New Deal in Congress); they argued the return of full employment made them superfluous. As a Republican President in the 1950s, Dwight D. Eisenhower left the New Deal largely intact. In the 1960s, Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society took New Deal policies further. After 1974, laissez faire views grew in support, calling for deregulation of the economy and ending New Deal regulation of transportation, banking and communications in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[3] Several New Deal programs remain active, with some still operating under the original names, including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The largest programs still in existence today are the Social Security System and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Origins

The New Deal represented a significant shift in political and domestic policy in the USA, its more lasting changes being increased federal government regulation of the economy. It also marked the beginning of complex social programs and growing power of labor unions. The effects of the New Deal remain a source of controversy and debate amongst economists and historians.[4]

Economists debate whether the causes of the depression and the effect of the 1929 stock market crash can be seen as a signal of the underlying economic issues, as opposed to a trigger for the crisis. Federal Reserve policy, the monetary rigidity of the gold standard, and overproduction are offered as possible factors in turning a cyclical downturn into a worldwide depression.

From 1929 to 1933, unemployment in the U.S. increased from 4% to 25%, and manufacturing output decreased by one third. Prices fell by 20%, causing a deflation which made the repayments of debts much harder. The mining, lumber, construction, and farming sectors were hit especially hard, along with railroads and heavy industries such as steel and automobiles. The impact was much less severe in the white-collar and service sectors.

Upon accepting the 1932 Democratic nomination for president, Franklin Roosevelt promised "a new deal for the American people".[5]:

“ Throughout the nation men and women, forgotten in the political philosophy of the Government, look to us here for guidance and for more equitable opportunity to share in the distribution of national wealth... I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people. This is more than a political campaign. It is a call to arms.[6] ” The Great Depression had devastated the nation. As Roosevelt took the oath of office at noon on March 4, 1933, the state governors had closed every bank in the nation; no one could cash a check or get at their savings.[7] The unemployment rate was 25% and higher in major industrial and mining centers. Farm income had fallen by over 50% since 1929. 844,000 nonfarm mortgages had been foreclosed, 1930–33, out of five million in all.[8] Political and business leaders feared revolution and anarchy. Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., who remained wealthy during the Depression, stated years later that "in those days I felt and said I would be willing to part with half of what I had if I could be sure of keeping, under law and order, the other half."[9]

Roosevelt entered office without a specific set of plans for dealing with the Great Depression; so he improvised as Congress listened to a very wide variety of voices.[10] The "First New Deal" (1933–34) encompassed the proposals offered by a wide spectrum of groups. (Not included was the Socialist Party, whose influence was all but destroyed.)[11] This first phase of the New Deal was also characterized by fiscal conservatism (see Economy Act, below) and experimentation with several different, sometimes contradictory, cures for economic ills. The consequences were uneven. Some programs, especially the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the silver program, have been widely seen as failures.[12][13] Other programs lasted about a decade; some became permanent. The economy shot upward, with FDR's first term marking one of the fastest periods of GDP growth in history. However a downturn in 1937–38 raised questions about just how successful the policies were, with the great majority of economists and historians agreeing they were an overall benefit.

The New Deal policies drew from many different ideas proposed earlier in the 20th century. Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold led efforts that hearkened back to an anti-monopoly tradition rooted in American politics by figures such as Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, an influential adviser to many New Dealers, argued that "bigness" (referring, presumably, to corporations) was a negative economic force, producing waste and inefficiency. However, the anti-monopoly group never had a major impact on New Deal policy.[14] Other leaders such as Hugh Johnson of the NRA took ideas from the Woodrow Wilson Administration, advocating techniques used to mobilize the economy for World War I. They brought ideas and experience from the government controls and spending of 1917–18. Other New Deal planners revived experiments suggested in the 1920s, such as the TVA.

Among Roosevelt's more famous advisers was an informal "Brain Trust": a group that tended to view pragmatic government intervention in the economy positively. Donald Richberg, the second head of the NRA, said "A nationally planned economy is the only salvation of our present situation and the only hope for the future."[15]

The New Deal faced some vocal conservative opposition. The first organized opposition in 1934 came from the American Liberty League led by conservative Democrats such as 1924 and 1928 presidential candidates John W. Davis and Al Smith. There was also a large but loosely affiliated group of New Deal opponents, who are commonly called the Old Right. This group included politicians, intellectuals, writers, and newspaper editors of various philosophical persuasions including classical liberals and conservatives, both Democrats and Republicans.

World comparisons

Europe

- Britain was unable to agree on major programs to stop its depression. This led to the collapse of the Labour Party government and its replacement in 1931 by a National Coalition dominated by Conservatives. However, the Depression affected Britain less than most countries due to Britain's exit from the gold standard in 1931 (which deal crisis and the Third Republic very much contested.[clarification needed])

- In France, the "Front Populaire" government, led by Léon Blum, in power 1936–1938, instigated major social reforms. As the coalition united representatives from the center-left to the communist party, right-wing opposition was very strong and social turmoil marred the Front Populaire term. This division left the country bitterly divided in 1938–1939.

- In Germany during the Weimar Republic, the economy spiraled down, leading to a political crisis and the rise to power of the Nazis in January 1933. Economic recovery was pursued through autarky, wage controls, price controls, and spending programs such as public works and, especially, military spending.

- Spain endured mounting political crises that led in 1936 to civil war.

- In Benito Mussolini's Italy, the economic controls of his corporate state were tightened.

- The Soviet Union was mostly isolated from the world trading system during the 1930s.

- Roosevelt's deal helped foreign economies recover, as well as the US's.

Canada & the Caribbean

- In Canada, Between 1929 and 1939, the gross national product dropped 40%, compared to 37% in the U.S. Unemployment reached 28% at the depth of the Depression in 1933. Many businesses closed, as corporate profits of C$396 million in 1929 turned into losses of $98 million in 1933. Exports shrank by 50% from 1929 to 1933. Worst hit were areas dependent on primary industries such as farming, mining and logging, as prices fell and there were few alternative jobs. Families saw most or all of their assets disappear and their debts became heavier as prices fell. Local and provincial government set up relief programs but there was no nationwide New-Deal-like program. The Conservative government of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett retaliated against the Smoot–Hawley tariff by raising tariffs against the U.S. but lowered them on British Empire goods. Nevertheless the economy suffered. In 1935, Bennett proposed a series of programs that resembled the New Deal; the proposals were all rejected and led to his defeat in the elections of 1935.[16]

- The Caribbean saw its greatest unemployment during the 1930s because of a decline in exports to the U.S., and a fall in export prices.

Asia

- China was at war with Japan during most of the 1930s, in addition to internal struggles between Chiang Kai Shek's nationalists and Mao Zedong's communists.

- Japan's economy expanded at the rate of 5% of GDP per year after the years of modernization. Manufacturing and mining came to account for more than 30% of GDP, more than twice the value for the agricultural sector. Most industrial growth, however, was geared toward expanding the nation's military power. Beginning in 1937 with significant land seizures in China, and then to a much greater extent after 1941, which saw annexations and invasions all across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, Japan seized and developed natural resources such as: sugarcane in the Philippines; petroleum from the Dutch East Indies and Burma; tin and bauxite from the Dutch East Indies and Malaya; and coal in China (where production increased from 15,000,000 t (17,000,000 short tons) in 1936, to 58,000,000 t (64,000,000 short tons) in 1942)[citation needed]. During the early stages of Japan's expansion, its economy expanded considerably. Iron production rose from 3,355,000 t (3,698,000 short tons) in 1937 to 6,148,000 t (6,777,000 short tons) in 1943[citation needed]. Steel production rose from 6,442,000 t (7,101,000 short tons) to 8,838,000 t (9,742,000 short tons) over the same time period. In 1941, Japanese aircraft industries had capacity to manufacture 10,000 aircraft per year. From 1941–September 1944, defense production (including airplanes and vessels) rose by 94%[citation needed].

Australia & New Zealand

- In Australia, 1930s conservative and Labor-led governments concentrated on cutting spending and reducing the national debt. It was not until World War II that the Australian government (first conservative, then Labor) introduced Keynesian policies similar to the New Deal; increasing taxes in order to fund stimulative spending, economic oversight/regulation, and rationing of petroleum products are prominent examples of an evolving view of the role of government in Australia throughout that period. Many progressive policies remained in place after the end of World War II. Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley outlined these policies in his "The light on the hill" speech.[citation needed]

- In New Zealand, a series of economic and social policies similar to the New Deal were adopted after the election of the first Labour Government in 1935.[17]

The First Hundred Days

Roosevelt entered office with enormous political capital. Americans of all political persuasions were demanding immediate action, and Roosevelt responded with a remarkable series of new programs in the “first hundred days” of the administration, in which he met with Congress for 100 days. During those 100 days of lawmaking, Congress granted every request Roosevelt asked, and passed a few programs (such as the FDIC to insure bank accounts) that he opposed. Ever since, presidents have been judged against FDR for what they accomplished in their first 100 days.

Bank and monetary reforms

With strident language Roosevelt took credit for dethroning the bankers he alleged had caused the debacle. On March 4, 1933, in his first inaugural address, he proclaimed:

Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. ... The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization.[18]He closed all the banks in the country and kept them all closed until he could pass new legislation.[19] On March 9, Roosevelt sent to Congress the Emergency Banking Act, drafted in large part by Hoover's top advisors. The act was passed and signed into law the same day. It provided for a system of reopening sound banks under Treasury supervision, with federal loans available if needed. Three-quarters of the banks in the Federal Reserve System reopened within the next three days. Billions of dollars in hoarded currency and gold flowed back into them within a month, thus stabilizing the banking system. By the end of 1933, 4,004 small local banks were permanently closed and merged into larger banks. (Their depositors eventually received on average 86 cents on the dollar of their deposits; it is a common false myth that they received nothing back.) In June 1933, over Roosevelt's objections, Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which insured deposits for up to $2,500 beginning January 1, 1934; this amount was increased to $5,000 on July 1, 1934. To deal with deflation, the nation went off the gold standard. In March and April in a series of laws and executive orders, the government suspended the gold standard for United States currency.[20] Anyone holding significant amounts of gold coinage was mandated to exchange it for the existing fixed price of US dollars, after which the US would no longer pay gold on demand for the dollar, and gold would no longer be considered valid legal tender for debts in private and public contracts. The dollar was allowed to float freely on foreign exchange markets with no guaranteed price in gold, only to be fixed again at a significantly lower level a year later with the passage of the Gold Reserve Act in 1934. Markets immediately responded well to the suspension, in the hope that the decline in prices would finally end.[21]

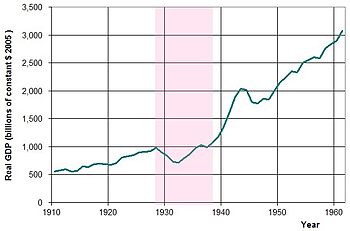

The economy had hit bottom in March 1933 and then started to expand. Economic indicators show the economy reached nadir in the first days of March, then began a steady, sharp upward recovery. Thus the Federal Reserve Index of Industrial Production sank to its lowest point of 52.8 in July 1932 (with 1935–39 = 100) and was practically unchanged at 54.3 in March 1933; however by July 1933, it reached 85.5, a dramatic rebound of 57% in four months. Recovery was steady and strong until 1937. Except for employment, the economy by 1937 surpassed the levels of the late 1920s. The Recession of 1937 was a temporary downturn. Private sector employment, especially in manufacturing, recovered to the level of the 1920s but failed to advance further until the war. Chart 2 below shows the growth in employment without adjusting for population growth. The U.S. population was 124,840,471 in 1932 and 128,824,829 in 1937, an increase of 3,984,468.[22] The ratio of these numbers, times the number of jobs in 1932, means there was a need for 938,000 more 1937 jobs to maintain the same employment level.

Economy Act

The Economy Act, drafted by Budget Director Christian McDonald was passed on March 14, 1933. The act proposed to balance the "regular" (non-emergency) federal budget by cutting the salaries of government employees and cutting pensions to veterans by fifteen percent. It saved $500 million per year and reassured deficit hawks, such as Douglas, that the new President was fiscally conservative. Roosevelt argued there were two budgets: the "regular" federal budget, which he balanced, and the "emergency budget", which was needed to defeat the depression; it was imbalanced on a temporary basis.[23]

Roosevelt was initially in favor of balancing the budget, but he soon found himself running spending deficits in order to fund the numerous programs he created. Douglas, however, rejecting the distinction between a regular and emergency budget, resigned in 1934 and became an outspoken critic of the New Deal. Roosevelt strenuously opposed the Bonus Bill that would give World War I veterans a cash bonus. Finally, Congress passed it over his veto in 1936, and the Treasury distributed $1.5 billion in cash as bonus welfare benefits to 4 million veterans just before the 1936 election.[24]

New Dealers never accepted the Keynesian argument for government spending as a vehicle for recovery. Most economists of the era, along with Henry Morgenthau of the Treasury Department, rejected Keynesian solutions and favored balanced budgets.[25]

Women and the New Deal

At first the New Deal created programs primarily for men. It was assumed that the husband was the "breadwinner" (the provider) and if they had jobs, whole families would benefit. It was the social norm for women to give up jobs when they married; in many states there were laws that prevented both husband and wife holding regular jobs with the government. So too in the relief world, it was rare for both husband and wife to have a relief job on FERA or the WPA.[26] This prevailing social norm of the breadwinner failed to take into account the numerous households headed by women, but it soon became clear that the government needed to help women as well.[27]

FERA camp for unemployed women, Maine, 1934

FERA camp for unemployed women, Maine, 1934

Many women were employed on FERA projects run by the states with federal funds. The first New Deal program to directly assist women was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), begun in 1935. It hired single women, widows, or women with disabled or absent husbands. While men were given unskilled manual labor jobs, usually on construction projects, women were assigned mostly to sewing projects. They made clothing and bedding to be given away to charities and hospitals. Women also were hired for the WPA's school lunch program. Both men and women were hired for the arts programs (such as music, theater and writing). The Social Security program was designed to help retired workers and widows, but did not include domestic workers, farmers or farm laborers, the jobs most often held by blacks. Social Security however was not a relief program and it was not designed for short-term needs, as very few people received benefits before 1942.

Artist Programs

An unusual branch of the WPA, Federal One, gave jobs to writers, musicians, artists, and theater personnel. Under the Federal Writer’s Project, a detailed guide book was prepared for every state, local archives were catalogued, and writers such as Margaret Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Anzia Yezierska were hired to document folklore. Other writers interviewed elderly ex-slaves and recorded their stories. Under the Federal Theater Project, headed by charismatic Hallie Flanagan, actresses and actors, technicians, writers, and directors put on stage productions. The tickets were inexpensive or sometimes free, making theater available to audiences unaccustomed to attending plays.[28] One Federal Art Project paid 162 trained woman artists on relief to paint murals or create statues for newly built post offices and courthouses. Many of these works of art can still be seen in public buildings around the country, along with murals sponsored by the Treasury Relief Art Project of the Treasury Department.[29][30]

Farm and rural programs

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), rural welfare projects sponsored by the WPA, NYA, Forest Service and CCC, including school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, reforestation, and purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests. In 1933, the Administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority, a project involving dam construction planning on an unprecedented scale in order to curb flooding, generate electricity, and modernize the very poor farms in the Tennessee Valley region of the Southern United States.

Roosevelt was keenly interested in farm issues and believed that true prosperity would not return until farming was prosperous. Many different programs were directed at farmers. The first 100 days produced the Farm Security Act to raise farm incomes by raising the prices farmers received, which was achieved by reducing total farm output. The Agricultural Adjustment Act created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) in May 1933. The act reflected the demands of leaders of major farm organizations, especially the Farm Bureau, and reflected debates among Roosevelt's farm advisers such as Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, M.L. Wilson, Rexford Tugwell, and George Peek.[31]

The aim of the AAA was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity. The AAA used a system of "domestic allotments", setting total output of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat. The farmers themselves had a voice in the process of using government to benefit their incomes. The AAA paid land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle with funds provided by a new tax on food processing. The goal was to force up farm prices to the point of "parity", an index based on 1910–1914 prices. To meet 1933 goals, 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of growing cotton was plowed up, bountiful crops were left to rot, and six million baby pigs were killed and discarded.[32] The idea was the less produced, the higher the wholesale price and the higher income to the farmer. Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose. Food prices remained well below 1929 levels.[33] A Gallup Poll printed in the Washington Post revealed that a majority of the American public opposed the AAA.[34]

The AAA established an important and long-lasting federal role in the planning on the entire agricultural sector of the economy and was the first program on such a scale on behalf of the troubled agricultural economy. The original AAA did not provide for any sharecroppers or tenants or farm laborers who might become unemployed, but there were other New Deal programs especially for them.

In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA to be unconstitutional, stating that "a statutory plan to regulate and control agricultural production, [is] a matter beyond the powers delegated to the federal government..." The AAA was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval. Instead of paying farmers for letting fields lie barren, this program instead subsidized them for planting soil enriching crops such as alfalfa that would not be sold on the market. Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but together with large subsidies it is still in effect in 2010.

The last major New Deal legislation concerning farming was in 1937, when the Farm Tenancy Act was created which in turn created the Farm Security Administration (FSA), replacing the Resettlement Administration.

A major new welfare program was the Food Stamp Plan established in 1939. It survives into the 21st century with little controversy because it benefits the urban poor, food producers, grocers and wholesalers, as well as farmers, thereby winning support from both liberal and conservative Congressmen.[35]

Repeal of Prohibition

In a measure that garnered substantial popular support for his New Deal, Roosevelt, on March 13, 1933, moved to put to rest one of the most divisive cultural issues of the 1920s. Just nine days later he signed the bill to legalize the manufacture and sale of alcohol, an interim measure pending the repeal of Prohibition, for which a constitutional amendment (the 21st) was already in process. The repeal amendment was ratified later in 1933. States and cities gained additional new revenue, and Roosevelt secured his popularity in the cities for supporting or permitting the legal production and sale of alcoholic beverages.[36][clarification needed]

Puerto Rico

A separate set of programs operated in Puerto Rico, headed by the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration. It promoted land reform and helped small farms; it set up farm cooperatives, promoted crop diversification, and helped local industry. The Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration was directed by Juan Pablo Montoya Sr. from 1935 to 1937.

Tax increases

In 1935, Roosevelt called for a tax program called the Wealth Tax Act to redistribute wealth, in which he proposed to increase inheritance tax, a gift tax, a severely graduated income tax, and a corporate income tax scaled according to income. However, Congress watered it down, by dropping the inheritance tax and only mildly increased the corporate tax.[37]

A tax called the Undistributed profits tax was enacted in 1936. The idea was to force businesses to distribute profits in dividend and wages, instead of saving or reinvesting them. Business profits were taxed on a sliding scale; if a company kept 1% of their net income, 10% of that amount would be taxed under the UP Tax. If a company kept 70% of their net income, the company would be taxed at a rate of 73.91% on that amount.[38] Facing widespread and fierce criticism, the tax was reduced to 2½% in 1938 and completely eliminated in 1939.[39]

Reform

Business, labor, and government cooperation

Besides all the programs for immediate relief, the federal government embarked quickly on an agenda of long-term reform aimed at avoiding another depression. The New Dealers responded to demands to inflate the currency by a variety of means.[40] Another group of reformers sought to build consumer and farmer co-ops as a counterweight to big business. The consumer co-ops did not take off, but the Rural Electrification Administration used co-ops to bring electricity to rural areas, many of which still operate.[41]

From 1929 to 1933, the industrial economy had been suffering from a vicious cycle of deflation. Since 1931, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the voice of the nation's organized business, promoted an anti-deflationary scheme that would permit trade associations to cooperate in government-instigated[42] cartels to stabilize prices within their industries. While existing antitrust laws clearly forbade such practices, organized business found a receptive ear in the Roosevelt Administration.[43] The Roosevelt Administration, packed with reformers aspiring to forge all elements of society into a cooperative unit (a reaction to the worldwide specter of business-labor "class struggle"), was fairly amenable to the idea of cooperation among producers.[44] FDR closed national banks on March 6, 1933, a day before he was officially inaugurated, to help stabilize the economy.[citation needed] Then three days later on March 9, he passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act to jumpstart money to flow in the economy.

The administration insisted that business would have to ensure that the incomes of workers would rise along with their prices. The product of all these impulses and pressures was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) which was passed by Congress in June 1933. The NIRA established the National Planning Board, also called the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB), to assist in planning the economy by providing recommendations and information. Fredric A. Delano, the president's uncle, was appointed head of the NRPB.[45]

The NIRA guaranteed to workers the right of collective bargaining and helped spur some union organizing activity, but much faster growth of union membership came before the 1935 Wagner Act. The NIRA established the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which attempted to stabilize prices and wages through cooperative "code authorities" involving government, business, and labor. The NRA allowed business to create a multitude of regulations imposing the pricing and production standards for all sorts of goods and services. Most economists were dubious because it was based on fixing prices to reduce competition; the NRA was ended by the Supreme Court in 1935, and no one tried to revive it.[46]

To prime the pump and cut unemployment, the NIRA created the Public Works Administration (PWA), a major program of public works. From 1933 to 1935 PWA spent $3.3 billion with private companies to build 34,599 projects, many of them quite large.[47]

NRA "Blue Eagle" campaign

Main article: National Recovery Administration NRA Blue Eagle

NRA Blue Eagle

Roosevelt believed that the severity of the Depression was due to excessive business competition that lowered wages and prices, which he believed lowered demand and employment.[42] He argued that government economic planning was necessary to remedy this:

...A mere builder of more industrial plants, a creator of more railroad systems, an organizer of more corporations, is as likely to be a danger as a help. Our task is not ... necessarily producing more goods. It is the soberer, less dramatic business of administering resources and plants already in hand.

New Deal economists argued that cut-throat competition had hurt many businesses and that with prices having fallen 20% and more, "deflation" exacerbated the burden of debt and would delay recovery. They rejected a strong move in Congress to limit the workweek to 30 hours. Instead their remedy, designed in cooperation with big business, was the NIRA. It included stimulus funds for the WPA to spend, and sought to raise prices, give more bargaining power for unions (so the workers could purchase more) and reduce harmful competition. At the center of the NIRA was the National Recovery Administration (NRA), headed by former General Hugh Johnson, who had been a senior economic official in World War I. Johnson called on every business establishment in the nation to accept a stopgap "blanket code": a minimum wage of between 20 and 45 cents per hour, a maximum workweek of 35–45 hours, and the abolition of child labor. Johnson and Roosevelt contended that the "blanket code" would raise consumer purchasing power and increase employment.[48]

To mobilize political support for the NRA, Johnson launched the "NRA Blue Eagle" publicity campaign to boost what he called "industrial self-government". The NRA brought together leaders in each industry to design specific sets of codes for that industry; the most important provisions were anti-deflationary floors below which no company would lower prices or wages, and agreements on maintaining employment and production. In a remarkably short time, the NRA announced agreements from almost every major industry in the nation. By March 1934, industrial production was 45% higher than in March 1933.[49] Donald Richberg, who soon replaced Johnson as the head of the NRA said:

There is no choice presented to American business between intelligently planned and uncontrolled industrial operations and a return to the gold-plated anarchy that masqueraded as "rugged individualism" ... Unless industry is sufficiently socialized by its private owners and managers so that great essential industries are operated under public obligation appropriate to the public interest in them, the advance of political control over private industry is inevitable.[50]

By the time NRA ended in May 1935, industrial production was 55% higher than in May 1933. On May 27, 1935, the NRA was found to be unconstitutional by a unanimous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Schechter v. United States. On that same day, the Court unanimously struck down the Frazier-Lemke Act portion of the New Deal as unconstitutional. Libertarian Richard Ebeling believes these and other rulings striking down portions of the New Deal prevented the U.S. economic system from becoming a planned economy corporate state.[51] Governor Huey Long of Louisiana said, "I raise my hand in reverence to the Supreme Court that saved this nation from fascism."[52]

However, soon after, on June 27, 1935, the NLRA was passed, which gave even more power to unions. It forced employees to join unions if a majority of employers voted in favor of unionizing and prohibited business management from declining to engage in collective bargaining with the unions. The Act also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to enforce the rules of the NLRA and enforce wage agreements.

Chart 3: Manufacturing employment in the United States from 1920 to 1940[53]

Chart 3: Manufacturing employment in the United States from 1920 to 1940[53]

Employment in private sector factories recovered to the level of the late 1920s by 1937 but did not grow much bigger until the war came and manufacturing employment leaped from 11 million in 1940 to 18 million in 1943.

Housing Sector

The New Deal had an important impact in the housing field. The New Deal followed and increased President Hoover's lead and seek measures. The New Deal sought to stimulate the private home building industry and increase the number of individuals who owned homes.[54] The New Deal implemented two new housing agencies; Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). HOLC “facilitated nation-wide lending and encouraged uniform national appraisal methods”.[54] The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) created national standards for home construction. The New Deal helped increase the number of Americans who owned homes. Before the New Deal only four out of 10 Americans owned homes; this was because the standard mortgage lasted only five to 10 years and had interest as high as 8%. These conditions severely limited the accessibility to housing for most Americans. Under the New Deal, Americans had access to 30-year mortgages, the standardized appraisal and construction standards helped open up the housing market to more Americans. Forty years after the implementation of the New Deal, ⅔ of Americans were home owners.[54]

Legislative successes and failures

In the spring of 1935, responding to the setbacks in the Court, a new skepticism in Congress, and the growing popular clamor for more dramatic action, the Administration proposed or endorsed several important new initiatives. Historians refer to them as the "Second New Deal" and note that it was more radical, more pro-labor and anti-business than the "First New Deal" of 1933–34. The National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, revived and strengthened the protections of collective bargaining contained in the original NIRA. The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions composing the American Federation of Labor. Labor thus became a major component of the New Deal political coalition. Roosevelt nationalized unemployment relief through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by close friend Harry Hopkins. It created hundreds of thousands of low-skilled blue collar jobs for unemployed men (and some for unemployed women and white collar workers). The National Youth Administration was the semi-autonomous WPA program for youth. Its Texas director, Lyndon Baines Johnson, later used the NYA as a model for some of his Great Society programs in the 1960s.

The most important program of 1935, and perhaps the New Deal as a whole, was the Social Security Act, which established a system of universal retirement pensions, unemployment insurance, and welfare benefits for poor families and the handicapped.[55] It established the framework for the U.S. welfare system. Roosevelt insisted that it should be funded by payroll taxes rather than from the general fund; he said, "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program." One of the last New Deal agencies was the United States Housing Authority, created in 1937 with some Republican support to abolish slums.

Defeat: court packing and executive reorganization

Main article: Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937Roosevelt, however, emboldened by the triumphs of his first term, set out in 1937 to consolidate authority within the government in ways that provoked powerful opposition. Early in the year, he asked Congress to expand the number of justices on the Supreme Court so as to allow him to appoint members sympathetic to his ideas and hence tip the ideological balance of the Court. This proposal provoked a storm of protest.

In one sense, however, it succeeded: Justice Owen Roberts switched positions and began voting to uphold New Deal measures, effectively creating a liberal majority in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish and National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, thus departing from the Lochner v. New York era and giving the government more power in questions of economic policies. Journalists called this change "the switch in time that saved nine". Recent scholars have noted that since the vote in Parrish took place several months before the court-packing plan was announced, other factors, like evolving jurisprudence, must have contributed to the Court's swing. The opinions handed down in the spring of 1937, favorable to the government, also contributed to the downfall of the plan. In any case, the "court packing plan", as it was known, did lasting political damage to Roosevelt[56] and was finally rejected by Congress in July.

Government role: balance labor, business, and farming

The federal government commissioned a series of public murals from the artists it employed. William Gropper's "Construction of a Dam" (1939), is characteristic of much of the art of the 1930s, with workers seen in heroic poses, laboring in unison to complete a great public project.

The federal government commissioned a series of public murals from the artists it employed. William Gropper's "Construction of a Dam" (1939), is characteristic of much of the art of the 1930s, with workers seen in heroic poses, laboring in unison to complete a great public project.The number of unemployed in 1929 was estimated at less than 4%, but by 1933 the unemployment rate had jumped up to approximately 25%. The New Deal was designed for complete economic recovery during the depression. However, the New Deal did not achieve full economic recovery. It actually had a limited economic impact. The New Deal failed to lower the unemployment rate below 14%. However, the New Deal did help maintain an average of 17% level the unemployment throughout the 1930s.[57] Most scholars believe that there were three versions of the New Deal in between 1933 and 1940. The first New Deal took place between 1933 and 1935 and was focused on both farm and factory. The second New Deal was introduced in 1935. In this New Deal, the country's welfare system was dramatically changed and expanded. One example of the New Deal’s new welfare programs was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which was created to “return the unemployed to the work force”.[57]

During the New Deal period, the federal government evolved into an arbitrator in the competition among elements and classes of society, acting as a force to help some groups and limit the power of others. This elevated and strengthened newer interest groups which allowed these to compete more effectively.

By the end of the 1930s, business found itself competing for influence with an increasingly powerful labor movement, with an organized agricultural economy, and occasionally with aroused consumers. This was accomplished by creating a series of government institutions that greatly and permanently expanded the role of the federal government. Thus, perhaps the strongest legacy of the New Deal was to make the federal government a protector of interest groups and a supervisor of competition among them.

As a result of the New Deal, political and economic life became more competitive than before, with workers, farmers, consumers, and others now able to press their demands upon the government in ways that in the past had been available only to the corporate world. Hence the frequent description of the government the New Deal created as the "broker state", a state brokering the competing claims of numerous groups[citation needed]. If there was more political competition, there was less market competition. Farmers were not allowed to sell for less than the official price. The transportation industry was tightly regulated so that every firm had a guaranteed market and management and labor had high profits and high wages, all at the cost of high prices and much inefficiency[citation needed]. Quotas in the oil industry were fixed by the Railroad Commission of Texas with Tom Connally's federal Hot Oil Act of 1935, which guaranteed that illegal "hot oil" would not be sold.[58] To the New Dealers, the free market meant "cut-throat competition" and they considered that evil.[citation needed] It was not until the 1970s and 1980s that most of the New Deal regulations were relaxed.

African Americans

Although many Americans suffered economically during the Great Depression, African Americans also had to deal with social ills, such as racism, discrimination, and segregation.

Many leading New Dealers, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Harold Ickes, Aubrey Williams, and John Flores Sr. worked to ensure blacks received at least 10% of welfare assistance payments.[59] There was no attempt whatsoever to end segregation, or to increase black rights in the South. Roosevelt appointed an unprecedented number of blacks to second-level positions in his administration; these appointees were collectively called the Black Cabinet. Roosevelt and Hopkins worked with several big city mayors to encourage the transition of black political organizations from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party from 1934 to 1936, most notably in Chicago. The black community responded favorably, so that by 1936 the majority who voted (usually in the North) were voting Democratic. This was a sharp realignment from 1932, when most African Americans voted the Republican ticket. New Deal policies helped establish a political alliance between blacks and the Democratic Party that survives into the 21st century.[60]

The WPA, NYA, and CCC relief programs allocated 10% of their budgets to blacks (who comprised about 10% of the total population, and 20% of the poor). They operated separate all-black units with the same pay and conditions as white units.[59]

However, these benefits were small in comparison to the economic and political advantages that whites received. Social Security was denied to blacks, and most unions excluded blacks from joining. Enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in the South was virtually impossible, especially since most blacks worked in hospitality and agricultural sectors.[61] The Farm Service Agency (FSA), a government relief agency for tenant farmers, created in 1937, made efforts to empower African Americans by appointing them to agency committees in the South. Senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina raised opposition to the appointments because he stood for white farmers who were threatened by an agency that could organize and empower tenant farmers.

Initially, the FSA stood behind their appointments, but after feeling national pressure FSA was forced to release the African Americans of their positions. The goals of the FSA were notoriously liberal and not cohesive with the southern voting elite.

Recession of 1937 and recovery

Main article: Recession of 1937The Roosevelt Administration was under assault during FDR's second term, which presided over a new dip in the Great Depression in the fall of 1937 that continued through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. Unemployment jumped from 14.3% in 1937 to 19.0% in 1938. Keynesian economists speculated that this was a result of a premature effort to curb government spending and balance the budget, while conservatives said it was caused by attacks on business and by the huge strikes caused by the organizing activities of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[62]

Roosevelt rejected the advice of Morgenthau to cut spending and decided big business were trying to ruin the New Deal by causing another depression that voters would react against by voting Republican.[63] It was a "capital strike" said Roosevelt, and he ordered the Federal Bureau of Investigation to look for a criminal conspiracy (they found none).[63] Roosevelt moved left and unleashed a rhetorical campaign against monopoly power, which was cast as the cause of the new crisis.[63] Ickes attacked automaker Henry Ford, steelmaker Tom Girdler, and the superrich "Sixty Families" who supposedly comprised "the living center of the modern industrial oligarchy which dominates the United States".[63] Left unchecked, Ickes warned, they would create "big-business Fascist America—an enslaved America". The President appointed Robert Jackson as the aggressive new director of the antitrust division of the Justice Department, but this effort lost its effectiveness once World War II began and big business was urgently needed to produce war supplies.[63]

But the Administration's other response to the 1937 dip that stalled recovery from of the Great Depression had more tangible results.[64] Ignoring the requests of the Treasury Department and responding to the urgings of the converts to Keynesian economics and others in his Administration, Roosevelt embarked on an antidote to the depression, reluctantly abandoning his efforts to balance the budget and launching a $5 billion spending program in the spring of 1938, an effort to increase mass purchasing power.[65] The New Deal had in fact engaged in deficit spending since 1933. Now they had a theory to justify what they were doing. Roosevelt explained his program in a fireside chat in which he told the American people that it was up to the government to "create an economic upturn" by making "additions to the purchasing power of the nation".

Business-oriented observers explained the recession and recovery in very different terms from the Keynesians. They argued that the New Deal had been very hostile to business expansion in 1935–37, had encouraged massive strikes which had a negative impact on major industries such as automobiles, and had threatened massive anti-trust legal attacks on big corporations. All those threats diminished sharply after 1938. For example, the antitrust efforts fizzled out without major cases. The CIO and AFL unions started battling each other more than corporations, and tax policy became more favorable to long-term growth.[66]

"When the Gallup poll in 1939 asked, 'Do you think the attitude of the Roosevelt administration toward business is delaying business recovery?' the American people responded 'yes' by a margin of more than two-to-one. The business community felt even more strongly so."[67] Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, angry at the Keynesian spenders, confided to his diary May 1939: "We have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent before and it does not work. And I have just one interest, and now if I am wrong somebody else can have my job. I want to see this country prosper. I want to see people get a job. I want to see people get enough to eat. We have never made good on our promises. I say after eight years of this administration, we have just as much unemployment as when we started.[68] And enormous debt to boot."

World War II and the end of the Great Depression

The Depression continued with decreasing effect until the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941. Under the special circumstances of war mobilization, massive war spending doubled the GNP (Gross National Product).[69] Civilian unemployment was reduced from 14% in 1940 to less than 2% in 1943 as the labor force grew by ten million. Millions of farmers left marginal operations, students quit school, and housewives joined the labor force. The effect continued into 1946, the first postwar year, where federal spending remained high at $62 billion (30% of GNP).[70]

The emphasis was for war supplies as soon as possible, regardless of cost and efficiencies. Industry quickly absorbed the slack in the labor force, and the tables turned such that employers needed to actively and aggressively recruit workers. As the military grew, new labor sources were needed to replace the 12 million men serving in the military. These events magnified the role of the federal government in the national economy. In 1929, federal expenditures accounted for only 3% of GNP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, but the national debt as percent of GNP hardly changed. However, spending on the New Deal was far smaller than spending on the war effort, which passed 40% of GNP in 1944. The war economy grew so fast after deemphasizing free enterprise and imposing strict controls on prices and wages, as a result of government/business cooperation, with government subsidizing business, directly and indirectly.[71]

A major result of the full employment at high wages was a sharp, permanent decrease in the level of income inequality. The gap between rich and poor narrowed dramatically in the area of nutrition, because food rationing and price controls provided a reasonably priced diet to everyone. White collar workers did not typically receive overtime thus the gap between white collar and blue collar income narrowed. Large families that had been poor during the 1930s had four or more wage earners, and these families shot to the top one-third income bracket. Overtime provided large paychecks in war industries.[72]

Critical interpretations of New Deal economic policies

See also: Critics of the New DealMany historians argue that Roosevelt restored hope and self-respect to tens of millions of desperate people, built labor unions, upgraded the national infrastructure and saved capitalism in his first term when he could have destroyed it and easily nationalized the banks and the railroads.[73] Some critics from the left, however, have denounced Roosevelt for rescuing capitalism when the opportunity was at hand to nationalize banking, railroads and other industries.[74] Still others have complained that he enlarged the powers of the federal government,[75] built up labor unions, slowed long-term economic growth, and weakened the business community. In his 1968 memoir The Brains Trust, Rexford Tugwell (a member of Roosevelt's Brain Trust) wrote that many New Deal laws “were tortured interpretations of a document intended to prevent them.”[76]

Keynesian and monetarist interpretations

The New Deal tried public works, farm subsidies, and other devices to reduce unemployment, but Roosevelt never completely gave up trying to balance the budget. Unemployment remained high throughout the New Deal years though greatly reduced from the much higher rates before the New Deal; business simply would not hire more people, especially the low skilled and supposedly "untrainable" men who had been unemployed for years and lost any job skill they once had. Keynesians later argued that by spending vastly more money — using fiscal policy — the government could provide the needed stimulus through the multiplier effect. Critics of Keynesian economic theories said that government spending would "crowd out" private investment and spending and thus not have any effect on the economy, a proposition known as the Treasury view, which Keynesian economics reject.

In recent years more influential among economists has been the monetarist interpretation of Milton Friedman, which did include a full-scale monetary history of what he calls the "Great Contraction". Friedman concentrated on the failures before 1933, particularly those of the Federal Reserve, and in his memoirs said the relief programs were an appropriate response.

Historians generally agree that apart from building up labor unions, the New Deal did not substantially alter the distribution of power within American capitalism. "The New Deal brought about limited change in the nation's power structure."[77]

Keynes visited the White House in 1934 to urge President Roosevelt to increase deficit spending. Roosevelt afterwards complained that, "he left a whole rigmarole of figures — he must be a mathematician rather than a political economist."[78]

File:Tax-spend.JPGConservative critics attacked New Deal policies as "Spend-and-Spend; Tax-and-Tax; Elect-and-Elect".Fiscal conservatism

Julian Zelizer (2000) has argued that fiscal conservatism was a key component of the New Deal.[citation needed] A fiscally conservative approach was supported by Wall Street and local investors and most of the business community; mainstream academic economists believed in it, as apparently did the majority of the public.[citation needed] Conservative southern Democrats, who favored balanced budgets and opposed new taxes, controlled Congress and its major committees. Even liberal Democrats at the time regarded balanced budgets as essential to economic stability in the long run, although they were more willing to accept short-term deficits. Public opinion polls consistently showed public opposition to deficits and debt.[citation needed] Throughout his terms, Roosevelt recruited fiscal conservatives to serve in his Administration, most notably Lewis Douglas the Director of Budget in 1933–1934, and Henry Morgenthau Jr., Secretary of the Treasury from 1934 to 1945. They defined policy in terms of budgetary cost and tax burdens rather than needs, rights, obligations, or political benefits. Personally the President embraced their fiscal conservatism. Politically, he realized that fiscal conservatism enjoyed a strong wide base of support among voters, leading Democrats, and businessmen. On the other hand, there was enormous pressure to act — and spending money on high visibility work programs with millions of paychecks a week.

Douglas proved too inflexible, and he quit in 1934. Morgenthau made it his highest priority to stay close to Roosevelt, no matter what. Douglas's position, like many of the Old Right, was grounded in a basic distrust of politicians and the deeply ingrained fear that government spending always involved a degree of patronage and corruption that offended his Progressive sense of efficiency. The Economy Act of 1933, passed early in the Hundred Days, was Douglas' great achievement. It reduced federal expenditures by $500 million, to be achieved by reducing veterans’ payments and federal salaries. Douglas cut government spending through executive orders that cut the military budget by $125 million, $75 million from the Post Office, $12 million from Commerce, $75 million from government salaries, and $100 million from staff layoffs. As Freidel concludes, "The economy program was not a minor aberration of the spring of 1933, or a hypocritical concession to delighted conservatives. Rather it was an integral part of Roosevelt's overall New Deal."[79] Revenues were so low that borrowing was necessary (only the richest 3% paid any income tax between 1926 and 1940.[80]) Douglas therefore hated the relief programs, which he said reduced business confidence, threatened the government’s future credit, and had the "destructive psychological effects of making mendicants of self-respecting American citizens".[81] Roosevelt was pulled toward greater spending by Hopkins and Ickes, and as the 1936 election approached he decided to gain votes by attacking big business.

Morgenthau shifted with FDR, but at all times tried to inject fiscal responsibility; he deeply believed in balanced budgets, stable currency, reduction of the national debt, and the need for more private investment. The Wagner Act met Morgenthau’s requirement because it strengthened the party’s political base and involved no new spending. In contrast to Douglas, Morgenthau accepted Roosevelt’s double budget as legitimate — that is a balanced regular budget, and an “emergency” budget for agencies, like the WPA, PWA and CCC, that would be temporary until full recovery was at hand. He fought against the veterans’ bonus until Congress finally overrode Roosevelt’s veto and gave out $2.2 billion in 1936. His biggest success was the new Social Security program; he managed to reverse the proposals to fund it from general revenue and insisted it be funded by new taxes on employees. It was Morgenthau who insisted on excluding farm workers and domestic servants from Social Security because workers outside industry would not be paying their way.[82]

Prolonged/worsened the Depression

In a survey of economic historians conducted by Robert Whaples, Professor of Economics at Wake Forest University, Whaples sent out anonymous questionnaires to members of the Economic History Association. Members were asked to either disagree, agree, or agree with provisos with the statement that read: "Taken as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression." While only 6% of economic historians who worked in the history department of their universities agreed with the statement, 27% of those that work in the economics department agreed. Almost an identical percent of the two groups (21% and 22%) agreed with the statement "with provisos" (a conditional stipulation), while 74% of those who worked in the history department, and 51% in the economic department disagreed with the statement outright.[83]

UCLA economists Harold L. Cole and Lee E. Ohanian are among those who believe the New Deal caused the Depression to persist longer than it would otherwise have, concluding in a study that the "New Deal labor and industrial policies did not lift the economy out of the Depression as President Roosevelt and his economic planners had hoped," but that the "New Deal policies are an important contributing factor to the persistence of the Great Depression." They claim that the New Deal "cartelization policies are a key factor behind the weak recovery". They say that the "abandonment of these policies coincided with the strong economic recovery of the 1940s".[84] Cole and Ohanian claimed that FDR's policies prolonged the Depression by 7 years.[85] However, Cole and Ohanian's argument relies on hypotheticals, including an unprecedented growth rate necessary to end the Depression by 1936,[86][87] and by not counting workers employed through New Deal programs. Such programs built or renovated 2,500 hospitals, 45,000 schools, 13,000 parks and playgrounds, 7,800 bridges, 700,000 miles (1,100,000 km) of roads, 1,000 airfields and employed 50,000 teachers through programs that rebuilt the country's entire rural school system.[88][89][90]

Lowell E. Gallaway and Richard K. Vedder argue that the "Great Depression was very significantly prolonged in both its duration and its magnitude by the impact of New Deal programs." They suggest that without Social Security, work relief, unemployment insurance, mandatory minimum wages, and without special government-granted privileges for labor unions, business would have hired more workers and the unemployment rate during the New Deal years would have been 6.7% instead of 17.2%.[91] In reply, Brad DeLong, economics professor and Deputy Assistant Secretary of the United States Department of the Treasury in the Clinton Administration under Lawrence Summers wrote that there is "literally nothing" to the arguments made by Gallaway and Vedder, and the duo made "flawed conclusions" based on "flawed foundations", and the entire foundation "is made out of mud".[92]

Contemporary public and business views about the economic effects of the New Deal were mixed and varied. In The Gallup Organization's May 1936 and March 1939 American Institute of Public Opinion (AIPO) polls, more than half of Americans reported that they felt the administration's policies were aiding recovery overall. Fortune's Roper poll found in May 1939 that 39% of Americans thought the administration had been delaying recovery by undermining business confidence, while 37% thought it had not. But it also found that opinions on the issue were highly polarized by economic status and occupation. In addition, AIPO found in the same time that 57% believed that business attitudes toward the administration were delaying recovery, while 26% thought they were not emphasizing that fairly subtle differences in wording can evoke substantially different polling responses.[93]

Left-wing criticism

Historians on the left have denounced the New Deal as a conservative phenomenon that let slip the opportunity to radically reform capitalism. Since the 1960s, "New Left" historians have been among the New Deal's harsh critics.[94] Barton J. Bernstein, in a 1968 essay, compiled a chronicle of missed opportunities and inadequate responses to problems. The New Deal may have saved capitalism from itself, Bernstein charged, but it had failed to help — and in many cases actually harmed — those groups most in need of assistance. Paul K. Conkin in The New Deal (1967) similarly chastised the government of the 1930s for its policies toward marginal farmers, for its failure to institute sufficiently progressive tax reform, and its excessive generosity toward select business interests. Howard Zinn, in 1966, criticized the New Deal for working actively to actually preserve the worst evils of capitalism.

Since the 1970s, research on the New Deal has been less interested in the question of whether the New Deal was a "conservative", "liberal", or "revolutionary" phenomenon than in the question of constraints within which it was operating. Political sociologist Theda Skocpol, in a series of articles, has emphasized the issue of "state capacity" as an often-crippling constraint. Ambitious reform ideas often failed, she argued, because of the absence of a government bureaucracy with significant strength and expertise to administer them. Other more recent works have stressed the political constraints that the New Deal encountered. Conservative skepticism about government remained strong both in Congress and among certain segments of the population. Thus some scholars have stressed that the New Deal was not just a product of its liberal backers, but also a product of the pressures of its conservative opponents.

Charges of communism

Certain critics have complained that the New Deal was infiltrated with communists. The most influential group was in the Department of Agriculture; its leaders fired in 1934, but one of them Alger Hiss went on to senior positions in foreign policy, while spying for the Soviet Union.[95][96] Outside government, the far-left was exerting considerable influence in the labor movement (it dominated parts of the new Congress of Industrial Organizations) and appealed to activists and intellectuals in building a network of front organizations that advocated policies approved by the Kremlin. Thus the American League Against War and Fascism was formed in 1933 and, in 1937, became the American League for Peace and Democracy. There followed the America Youth Congress, 1934; League of American Writers, 1935; National Negro Congress, 1936; and the American Congress for Democracy and Intellectual Freedom, 1939. All had significant Communist elements, and fought furious battles with the anti-communist left.[97]

Charges of fascism

Further information: The New Deal and corporatism and Fascism and ideologyIn the 1930s fascism was considered a legitimate political ideology, combining an intense, authoritarian nationalism with a planned economy and corporativism exemplified by the economic plans of Benito Mussolini in Italy. Enemies of the New Deal sometimes called it "fascist", but meant very different things. Communists, for example, meant control of the New Deal by big business. Classical liberals and conservatives meant control of big business by bureaucrats (also labeled with the term of "socialism," as in Ludwig von Mises' book, The Free and Prosperous Commonwealth).

Former President Herbert Hoover argued that some (but not all) New Deal programs were "fascist":[98]

"Among the early Roosevelt fascist measures was the National Industry Recovery Act (NRA) of June 16, 1933 .... These ideas were first suggested by Gerald Swope (of the General Electric Company)... [and] the United States Chamber of Commerce. During the campaign of 1932, Henry I. Harriman, president of that body, urged that I agree to support these proposals, informing me that Mr. Roosevelt had agreed to do so. I tried to show him that this stuff was pure fascism; that it was a remaking of Mussolini's "corporate state" and refused to agree to any of it. He informed me that in view of my attitude, the business world would support Roosevelt with money and influence. That for the most part proved true."

In 1934, Roosevelt defended himself against his critics, and attacked them in his "fireside chat" radio audiences. Some people, he said:

will try to give you new and strange names for what we are doing. Sometimes they will call it 'Fascism,' sometimes 'Communism,' sometimes 'Regimentation,' sometimes 'Socialism.' But, in so doing, they are trying to make very complex and theoretical something that is really very simple and very practical.... Plausible self-seekers and theoretical die-hards will tell you of the loss of individual liberty. Answer this question out of the facts of your own life. Have you lost any of your rights or liberty or constitutional freedom of action and choice?[99]

In September 1934, Roosevelt defended a more powerful national government which he believed was necessary to control the economy, by quoting conservative Republican Elihu Root:

The tremendous power of organization [Root had said] has combined great aggregations of capital in enormous industrial establishments... so great in the mass that each individual concerned in them is quite helpless by himself.... The old reliance upon the free action of individual wills appears quite inadequate.... The intervention of that organized control we call government seems necessary.... Men may differ as to the particular form of governmental activity with respect to industry or business, but nearly all are agreed that private enterprise in times such as these cannot be left without assistance and without reasonable safeguards lest it destroy not only itself but also our process of civilization.[99]

Other scholars reject linking the New Deal to fascism as overly simplistic. As a leading historian of fascism explains, "What Fascist corporatism and the New Deal had in common was a certain amount of state intervention in the economy. Beyond that, the only figure who seemed to look on Fascist corporatism as a kind of model was Hugh Johnson, head of the National Recovery Administration",[100] Johnson had been distributing copies of a Fascist tract called "The Corporate State" by one of Mussolini's favorite economists, including giving one to Labor Secretary Frances Perkins and asking her give copies to her cabinet.[101] Johnson strenuously denied any association with Mussolini, saying the NRA "is being organized almost as you would organize a business. I want to avoid any Mussolini appearance—the President calls this Act industrial self-government."[102] Donald Richberg eventually replaced Johnson as head of NRA, and speaking before a Senate committee said "A nationally planned economy is the only salvation of our present situation and the only hope for the future."[15] Historians such as Hawley (1966) have examined the origins of the NRA in detail, showing the main inspiration came from Senators Hugo Black and Robert F. Wagner and from American business leaders such as the Chamber of Commerce. The main model was Woodrow Wilson's War Industries Board, in which Johnson had been involved.

The works of art and music

The Works Progress Administration subsidized artists, musicians, painters and writers on relief with a group of projects called Federal One. While the WPA program was by the most widespread, it was preceded by three programs administered by the US Treasury which hired commercial artists at usual commissions to add murals and sculptures to federal buildings. The first of these efforts was the short-lived Public Works of Art Project, organized by Edward Bruce, an American businessman and artist. Bruce also led the Treasury Department's Section of Painting and Sculpture (later renamed the Section of Fine Arts) and the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP). The Resettlement Administration (RA) and Farm Security Administration (FSA) had major photography programs. The New Deal arts programs emphasized regionalism, social realism, class conflict, proletarian interpretations, and audience participation. The unstoppable collective powers of common man, contrasted to the failure of individualism, was a favorite theme.[103][104]

Post Office murals and other public art, painted by artists in this time, can still be found at many locations around the U.S.[105] The New Deal particularly helped American novelists. For journalists, and the novelists who wrote non-fiction, the agencies and programs that the New Deal provided, allowed these writers to describe about what they really saw around the country.[106]

Many writers chose to write about the New Deal, and whether they were for or against it, and if it was helping the country out. Some of these writers were Ruth McKenney, Edmund Wilson, and Scott Fitzgerald.[107] Another subject that was very popular for novelists was the condition of labor. They ranged from subjects on social protest, to strikes.[108]

Under the WPA, the Federal Theatre project flourished. Countless theatre productions around the country were staged. This allowed thousands of actors and directors to be employed, among them were Orson Welles, and John Huston.[105]

The FSA photography project is most responsible for creating the image of the Depression in the U.S. Many of the images appeared in popular magazines. The photographers were under instruction from Washington as to what overall impression the New Deal wanted to give out. Director Roy Stryker's agenda focused on his faith in social engineering, the poor conditions among cotton tenant farmers, and the very poor conditions among migrant farm workers; above all he was committed to social reform through New Deal intervention in people's lives. Stryker demanded photographs that "related people to the land and vice versa" because these photographs reinforced the RA's position that poverty could be controlled by "changing land practices". Though Stryker did not dictate to his photographers how they should compose the shots, he did send them lists of desirable themes, such as "church", "court day", "barns".[109] Films of the late New Deal era such as Citizen Kane (1941) ridiculed so-called "great men", while class warfare (typified by new taxes on the rich[110]) appeared in numerous movies, such as The Grapes of Wrath (1940). Thus in Frank Capra's famous films, including Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Meet John Doe (1941) and It's a Wonderful Life (1946), the common people come together to battle and overcome villains who are corrupt politicians controlled by very rich, greedy capitalists.[111]

By contrast there was also a smaller but influential stream of anti-New Deal art. Thus Gutzon Borglum's sculptures on Mount Rushmore emphasized great men in history (his designs had the approval of Calvin Coolidge). Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway disliked the New Deal and celebrated the organic autonomy of perfected written work in opposition to the New Deal trope of writing as performative labor. The Southern Agrarians celebrated a premodern regionalism and opposed the TVA as a modernizing, disruptive force. Cass Gilbert, a conservative who believed architecture should reflect historic traditions and the established social order, designed the new Supreme Court building (1935). Its classical lines and small size contrasted sharply with the gargantuan modernistic federal buildings going up in the Washington Mall that he detested.[112] Hollywood managed to synthesize liberal and conservative streams, as in Busby Berkeley's Gold Digger musicals, where the storylines exalt individual autonomy while the spectacular musical numbers show abstract populations of interchangeable dancers securely contained within patterns beyond their control.[113]

Legacies

The New Deal was the inspiration for President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society in 1960s. Johnson (on right) headed the Texas NYA and was elected to Congress in 1938.

The New Deal was the inspiration for President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society in 1960s. Johnson (on right) headed the Texas NYA and was elected to Congress in 1938.

Analysts agree the New Deal produced a new political coalition that sustained the Democratic Party as the majority party in national politics for more than a generation after its own end.

During Roosevelt's 12 years in office, there was a dramatic increase in the power of the federal government as a whole. Roosevelt also established the presidency as the prominent center of authority within the federal government. Roosevelt created a large array of agencies protecting various groups of citizens — workers, farmers, and others — who suffered from the crisis, and thus enabled them to challenge the powers of the corporations. In this way, the Roosevelt Administration generated a set of political ideas — known as New Deal liberalism — that remained a source of inspiration and controversy for decades and that helped shape the next great experiment in liberal reform, the Great Society of the 1960s.

The wartime FEPC executive orders that forbade job discrimination against African Americans, women, and ethnic groups was a major breakthrough that brought better jobs and pay to millions of minority Americans. Historians usually treat FEPC as part of the war effort and not part of the New Deal itself.

Political metaphor

Since 1933, politicians and pundits have often called for a "new deal" regarding an object. That is, they demand a completely new, large-scale approach to a project. As Arthur A. Ekirch Jr. (1971) has shown, the New Deal stimulated utopianism in American political and social thought on a wide range of issues. In Canada, Conservative Prime Minister Richard B. Bennett in 1935 proposed a "new deal" of regulation, taxation, and social insurance that was a copy of the American program; Bennett's proposals were not enacted, and he was defeated for reelection in October 1935. In accordance with the rise of the use of U.S. political phraseology in Britain, the Labour Government of Tony Blair has termed some of its employment programs "new deal", in contrast to the Conservative Party's promise of the 'British Dream'.

New Deal Programs

The New Deal had many programs and new agencies, most of which were universally known by their initials. They included the following. Most were abolished during World War II; others remain in operation today:

- Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) a Hoover agency expanded under Jesse Holman Jones to make large loans to big business. Ended in 1954.

Some WPA programs included adult education.

Some WPA programs included adult education.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) a Hoover program to create unskilled jobs for relief; replaced by WPA in 1935.

- United States bank holiday, 1933: closed all banks until they became certified by federal reviewers

- Abandonment of gold standard, 1933: gold reserves no longer backed currency; still exists

- Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), 1933–1942: employed young men to perform unskilled work in rural areas; under United States Army supervision; separate program for Native Americans