- Common Vampire Bat

-

Common Vampire Bat

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Chiroptera Family: Phyllostomidae Subfamily: Desmodontinae Genus: Desmodus Species: D. rotundus Binomial name Desmodus rotundus

Geoffroy, 1810

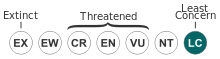

The Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus) is a small leaf-nosed bat native to the Americas. It is one of three extant species of vampire bat, the other two being the Hairy-legged Vampire Bat and the White-winged Vampire Bat. Along with them, it is the only parasitic mammal. It mainly feeds on the blood of livestock and is considered a pest. It is also a carrier of rabies. The conservation status of the bat is categorized as Least Concern by the IUCN because of "its wide distribution, presumed large population tolerance of a degree of habitat modification, and because it is unlikely to be declining at nearly the rate required to qualify for listing in a threatened category."[1]

Contents

Physical description

Common Vampire Bats have burnt-amber colored fur on their backside while soft and velvety light brown fur covers their belly. They have large pointy ears and a flat leaf-shaped nose. They a well-developed clawed thumb on each wing, which are used to climb on prey. Vampire bats are about 9 cm (3.5 in) long and have a wingspan of 18 cm (7 in). They commonly weigh about 57 grams (2 oz), but that can double after just one feeding.[2] Vampire bats have sexual dimorphism in favor of females,[3] a trait unusual among bats. The vampire bat has a relatively large braincase and its rostrum is reduced to accommodate large razor-sharp incisors and canines. The upper incisors lack enamel, which keeps them permanently razor sharp.[4] Vampire bats also have the fewest teeth among the bats. The tongue has two lateral grooves that expand and contract as the bat feeds.

While most other bats have almost lost the ability to maneuver on land, vampire bats can run by using a unique bounding gait. The forelimbs instead of the hind limbs are used for force production since the wings are much more powerful than the legs. This likely evolved independently within the bat lineage.[5] It is also capable of doing leaps in various directions, magnitudes and temporal sequences.[6] When making a jump, the bat uses its pectoral limbs to generate an upward thrust. The hindlimbs act as stablizers and orient the body over the pectoral limbs and the thumbs or pollices stabilize the pectoral limb and contribute to extending the time over which vertical force is exerted.[7]

Common Vampire Bats have fairly good eyesight compared to other bats. They have a visual acuity angle of 0.7, and are able to detect single cattle at 130 m.[8] They also emit echolocation signals, orally and thus fly with their mouths open for navigation. Their capabilities have a threshold of identity of 0.5 mm wires, which is moderate compared to another bats.

Range and habitat

The Common Vampire Bat is found in parts of Mexico, Central America and South America.[9] It can be found as far north as 175 mi from the US border. Fossils have been found of this bat in border states and in Florida. These places provide suitable habitat for the bat and it has been suggested that it may "have yet to reoccupy" these places.[10] In addition it is the most common species in southeastern Brazil.[11] The southern extent of its range is Uruguay, northern Argentina, and central Chile. In the West Indies, the bat is only found on Trinidad. The vampire bat is an ecologically flexible species and lives in rainforests, arid coastal plains, mountains, brush and mesquite plains and deserts. It prefers warm and humid climates.[12][13]

Bats roost in trees, caves, abandoned buildings, old wells, and mines.[12][14] Vampire bats will roost with nine other bat species and tend to be the most dominate at roosting sites.[14] The bats occupy the darkest and highest places in the roosts and when they leave, other bat species move in to take over these vacated spots. Vampire bats can thermoregulate down to 0°C.[9]

Behavior

Feeding

The Common Vampire Bat feeds primarily on mammal blood, particularly that of livestock such as cattle and horses.[12] Vampire bats will feed on wild prey like tapirs but seem to prefer domesticated ones. Bats prefer to feed on horses over cattle when given the choice.[15] Female prey, particularly those in estrous, are more often targeted than males. This could be because they tend to be on the perimeter of the herd[8] or perhaps because of the hormones.[16] Young animals are also preferred over adults, possibly because of their thinner skin or because that are less active at night.[8]

Vampire bats hunt at night.[12] They leave their roosts in an orderly fashion. Bachelor males are the first to leave, followed by the females and lastly, the harem males.[17]

The bats use hearing and smell to track down prey.[18] They tend to feed in an area 5–8 km from their roost.[19] When a bat targets a victim, it will land on it or walk and jump on it.[12][19] The bat the sometimes lands near the prey and feeds on it from the ground. The victim doesn’t feel the land on it as the bat has padded feet and wrists.[20]

"In addition to excellent vision, sense of smell, and acute hearing, vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus) have heat detectors on their noseleaf."[21]

The heat sensors in the nose help the bat detect a blood vessel near the surface.[15][22] Vampire bats commonly return to the same host on consecutive nights. They mark their host with urine. Vampire bats are also protective of their host and will fend off any other bat that lands while it is feeding.[13][18] Thus it is uncommon for two or more bats to feed on the same host and cases of such are usually mothers and their offspring.[13][18]

When feeding, vampire bats target the rump, flanks or neck of the victim.[12] Bats use their razor sharp teeth to pull a flap of skin off the victim.[19] A bat uses its tongue to lap up the blood. The blood is kept flowing by an anticoagulant which the bat has in its saliva.[19] The kidneys of the vampire bat are effective in extracting water from the blood when it is feeding, so the bat can consume more blood without being overloaded with water.[20] A bat will feed for thirty minutes and will become swollen with blood.[12] At this time the bat can barely fly and it will hide and wait until its body processes the blood enough to the point where it can fly.[20]

Mating and reproduction

Male vampire bats defend and maintain roosting sites that attract or contain females.[23] A male and his females make up a harem. A harem male is the only male that mates with the females.[12] Females in a harem rarely mate with an outside male, despite having opportunities to do so.[12] Bachelor males will try to mate with females when possible but the females usually refuse them.[24] Vampire bat harems may also contain multiple males maintaining and defending a roosting site.[17] In the groups, the males have a dominance hierarchy, with the most dominant male fathering most of the offspring (which is about half),[18] the next dominant male fathering the second most offspring and so on.[24] In multiple male harems, a female may reject mating with the dominant male possibly to avoid inbreeding.[17] Harems males defend their territories from intruders even after females have left.[23]

During estrous, a female will release only one egg despite both ovaries being functional.[23] Mating usually lasts 1–3 minutes.[8] The male bat will mount the female from the posterior end.[8] He grasps her back with his teeth and inseminates her. After mating, the male leaves a vaginal plug containing sperm in the female.[25] Vampire bats are reproductively active all year around, although peaks in conceptions and births occur in the rainy season.[12][19] The gestation period of a common vampire bat lasts about 205 days. Females give birth to one offspring per pregnancy.[12][19] Raising of the young is done primarily by the females. Young are fed their mother’s milk for the first three months and are then fed mixtures of milk and regurgitated blood.[3] A mother will leave the young in the roost when she goes to feed,[12] and upon returning, calls her young so she can feed it regurgitated blood. Young will accompany their mothers in hunts at six months but are not fully weaned until nine months.[12] Female offspring usually remain in their natal groups unless their mothers die or move.[24] Several matrilines can be found in a group as unrelated females regularly join groups.[24] Nevertheless, females are usually reluctant to join a new group as a bat survival rate depends on long lasting social bonds.[15][24] A female who enters a new group may not incorporate into that group's social activities.[24] Male offspring tend to live their natal groups until they are about two years old, sometimes being forcefully expelled by the resident adult males.[24]

Cooperation

Common vampire bats display a high amount of cooperative behaviors. Females in a harem have strong social bonds that are reinforced through interactions in the roost.[15] A harem male has moderately strong relationships with his females.[26] In harems with multiple males, the males may have social bonds but they are not as strong as those of the females.[18] While the harem males relations with outside bachelors males is mostly agonistic, bachelor males are accepted into the harems when the ambient temperature lowers, possibly a form of social thermoregulation.[3] A notable cooperative behavior among bats is reciprocal altruism, which is when bats share food with each other.[15] In food sharing a bat regurgitates blood to feed to another bat.[12] Some bats are unsuccessful in feeding and will thus solicit blood from a roost mate.[15][18] This behavior likely evolved to combat starvation[26] as a bat cannot live for more than three nights without blood.[15] In addition to the females sharing blood with one another, the harem male will also share blood with his females.[26] Harem males may also share food with each other.[26]

Female vampire bats also display alloparenting.[15] Lactating females in roosts will feed both young whose mothers have died and those whose mothers are still alive.[24] This mechanism evolved to keep the young from starving as well help with the burden of raising offspring.[3] Vampire bats will also participate in mutual grooming.[18] Two bats will groom each other simultaneously.[27] In addition to cleaning, bats may also groom to strengthen social bonds between those that share blood.[27] Bats who groom one another also share food.[23] With grooming, a bat can assess if a bat that is begging for food is well feed or if it is really starving.[27] A bat will assess the swollenness of its partner’s body to see if it really needs food.[27] Grooming is also dependent on kinship and relatedness.[27] Mothers groom offspring more than other bats and this may promote recognition in parent and offspring.[27]

Relationship with humans

Worker holding Common Vampire Bat. Trinidad, 1956. Courtesy of the Greenhall's Trust - WI

Worker holding Common Vampire Bat. Trinidad, 1956. Courtesy of the Greenhall's Trust - WI

Only 0.5% of bats carry rabies. However, of the few cases of rabies reported in the United States every year, most are caused by bat bites.[28] The highest occurrence of rabies in vampire bats occurs in the large populations found in South America. However there is less risk of infection to the human population than to livestock exposed to bat bites.[29] Dr. Joseph Lennox Pawan, a Government Bacteriologist in Trinidad, the West Indies, found the first infected vampire bat in March 1932.[30] He then soon proved that various species of bat including the Common Vampire Bat, with or without artificial infection or the external symptoms of rabies are capable of transmitting rabies for an extended period of time.[30] "Perhaps, the most heretical disclosure was that vampire bats could recover from the furious stage of the disease and were capable of spreading the disease up to five and one half months." It was later shown that fruit bats of the Artibes genus demonstrate the same abilities. During this asymptomatic stage the bats continue to behave normally and breed. At first, his basic findings that bats transmitted rabies to people and animals were thought fantastic and ridiculed.[30]

Although most bats do not have rabies, those that do may be clumsy, disoriented, and unable to fly, which makes it more likely that they will come into contact with humans. There is evidence that it is possible for the bat rabies virus to infect victims purely through airborne transmission, without direct physical contact of the victim with the bat itself.[31][32] Although one should not have an unreasonable fear of bats, one should avoid handling them or having them in one's living space, as with any wild animal. If a bat is found in living quarters near a child, mentally handicapped person, intoxicated person, sleeping person, or pet, the person or pet should receive immediate medical attention for rabies. Bats have very small teeth and can bite a sleeping person without being felt.

The unique properties of the vampire bats' saliva have found some positive use in medicine. A study which tested a genetically engineered drug called desmoteplase, which uses the anticoagulant properties of the saliva of Desmodus rotundus, and was shown to increase blood flow in stroke patients.[33]

See also

References

- ^ a b Barquez, R., Perez, S., Miller, B. & Diaz, M. (2008). "Desmodus rotundus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/6510. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Common Vampire Bat Desmodus rotundus Nat Geo Wild

- ^ a b c d Delpietro V. & Russo, R. G. (2002) "Observations of the Common Vampire Bat and the Hairy-legged Vampire Bat in Captivity", Mamm. Biol, 67:65-78. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00011

- ^ Greenhall, Arthur M. (1988) "Feeding Behavior". In: Natural History of Vampire Bats (ed. by A. M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt), 111-132. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- ^ Riskin, Daniel K. and John W. Hermanson. (2005) "Biomechanics: Independent evolution of running in vampire bats", Nature 434:292-292. Abstract, video.

- ^ Altenbach, J. S. (1979) "Locomotor morphology of the vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus", Special publication (American Society of Mammalogists), no. 6.

- ^ Schutt, W.A., Jr., Hermanson, J.W., Chang, Y.H., Cullinane, D., Altenbach, J.S., Muradali, F. and J.E.A. Bertram. (1997) "The dynamics of flight-initiating jumps in the common vampire bat Desmodus rotundus". The Journal of Experimental Biology 200(23): 3003-3012.

- ^ a b c d e Turner, Dennis C (1975) The Vampire Bat: a Field Study in Behavior and Ecology, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press.

- ^ a b Hill, J. E., and James D. Smith (1984). Bats: A Natural History. Austin, TX, University of Texas Press.

- ^ Ray, Clayton E; Linares, Omar J; Morgan, Gary S. (1988) In: Natural History of Vampire Bats (ed. by A. M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt), 19-30. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- ^ Trajano, E. (1996) "Movements of Cave Bats in Southeastern Brazil, With Emphasis on the Population Ecology of the Common Vampire Bat, Desmodus rotundus (Chiroptera)". Biotropica 28:121-129. Abstract

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lord, R. D. (1993) "A Taste for Blood: The Highly Specialized Vampire Bat Will Dine on Nothing Else". Wildlife Conservation 96:32-38.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson, G. S. (1985) "The Social Organization of the Common Vampire Bat 1: Pattern and Cause of Association". Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 17:111-121.

- ^ a b Wohlgenant, T. (1994) "Roost Interactions Between the Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus) and Two Frugivorous Bats (Phyllostomus discolor and Sturnira lilium) in Guanacaste, Costa Rica". Biotropica 26:344-348. Abstract

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson. G., (1990) "Food Sharing in Vampire Bats". Scientific American, 262(21):76-82.

- ^ Schutt, W.A, Jr.; Muradali, F; Mondol N; Joseph, K; and Brockmann, K. (1999) "Behavior and Maintenance of Captive White-Winged Vampire Bats, Diaemus youngi". Journal of Mammology. 80(1): 71-81. Abstract

- ^ a b c Park, S. R. (1991) "Development of Social Structure in a Captive Colony of the Common Vampire Bat", Desmodus rotundus. Ethology 89:335-341. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1991.tb00378.x

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilkinson, J. (2001) Bat Blood Donors. (Ed. by D. MacDonald & S. Norris), 766-767. In: The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, New York: Facts on File.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowak, R. M. (1991) Walker's Mammals of the World. pp. 1629. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins Press.

- ^ a b c Altringham J. D. (1998) The Insectivorous Bats. pp. 262. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ M. Brock Fenton. (2011) "The World Through a Bat's Ear." Science 333:29 2011, Abstract

- ^ "What Steers Vampires to Blood"

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson, G. S. (1988) "Social Organization and Behavior". (Ed. by A. M. Greenhall & U. Schmidt), pp. 85-97. In: Natural History of Vampire Bats. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, G. (1985) "The Social Organization of the Common Vampire Bat II: Mating system, genetic structure, and relatedness", Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol, 17:123-134.

- ^ Schmidt, C. (1988) "Reproduction". (Ed. by A. M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt), pp. 97-107. In: Natural History of Vampire Bats. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

- ^ a b c d DeNault L. K. & MacFarlane, D. (1995) "Reciprocal altruism between male vampire bats, Desmodus rotundus". Anim. Behav. 49:855-856.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilkinson, G. S. (1986) "Social Grooming in the Common Vampire Bat, Desmodus rotundus". Anim. Behav. 34:1880-1889.

- ^ Gibbons, Robert V.; Charles Rupprecht (2000). "Twelve Common Questions About Human Rabies and Its Prevention" (PDF). Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins) 9 (5): 202–207. doi:10.1097/00019048-200009050-00005. ISSN 1056-9103. http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/docs/12_questions_rabies.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-29. "Excluding dog bites that occurred outside of the country, 22 of the 31 (71%) human cases of rabies in the United States since 1980 have been associated with bat rabies virus variants." Note: the 71% figure in the quote would be for the 20 year period from 1980 to c.2000.

- ^ Bat Facts Smithsonian

- ^ a b c Joseph Lennox Pawan Caribbean Council for Science and Technology

- ^ Constantine, Denny G. (April 1962). "Rabies transmission by nonbite route". Public Health Reports (Public Health Service) 77 (4): 287–289. PMC 1914752. PMID 13880956. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1914752. "These findings support consideration of an airborne medium, such as an aerosol, as the mechanism of rabies transmission in this instance."

- ^ Messenger, Sharon L.; Jean S. Smith and Charles E. Rupprecht (2002-09-15). "Emerging Epidemiology of Bat-Associated Cryptic Cases of Rabies in Humans in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases 35 (6): 738–747. doi:10.1086/342387. PMID 12203172. "Cryptic rabies cases are those in which a clear history of exposure to rabies virus cannot be documented, despite extensive case‐history investigation. Absence of a documented bite history reflects inherent difficulties in obtaining accurate animal‐contact information.... <gap> Thus, absence of bite‐history data does not mean that a bite did not occur."

- ^ Liberatore, G. T., Samson, A., Bladin, C., Schleuning, W., Medcalf, R. (2003) "Vampire Bat Salivary Plasminogen Activator (Desmoteplase) A Unique Fibrinolytic Enzyme That Does Not Promote Neurodegeneration", Stroke 34:537-543.

Further reading

- Greenhall, Arthur M. 1961. Bats in Agriculture. A Ministry of Agriculture Publication. Trinidad and Tobago.

- Greenhall, Arthur M. 1965. The Feeding Habits of Trinidad Vampire Bats.

- Greenhall, A., G. Joermann, U. Schmidt, M. Seidel. 1983. Mammalian Species: Desmodus rotundus. American Society of Mammalogists, 202: 1-6.

- A.M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt, editors. 1988. Natural History of Vampire Bats, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. ISBN 0849367506; ISBN 978-0849367502

- Joseph Lennox Pawan,(1936). "Transmission of the Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad of the Vampire Bat: Desmodus rotundus murinus Wagner, 1840." Annual Tropical Medicine and Parasitol, 30, April 8, 1936:137-156.

- Pawan, J.L. (1936b). "Rabies in the Vampire Bat of Trinidad with Special Reference to the Clinical Course and the Latency of Infection." Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parisitology. Vol. 30, No. 4. December, 1936

- Walker, Steven. 1996. Desmodus. University Editions. Virginia. ISBN 1-56002-637-5

- Kishida R, Goris RC, Terashima S, Dubbeldam JL. (1984) A suspected infrared-recipient nucleus in the brainstem of the vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus. Brain Res. 322:351-5.

- Campbell A, Naik RR, Sowards L, Stone MO. (2002) Biological infrared imaging and sensing. Micron 33:211-225. pdf.

External links

- ARKive - images and movies of the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus)

- National Geographic site with photos and other media. [1]

- Biogeography of the Vampire Bat. [2]

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Fauna of Mexico

- Bats of South America

- Mammals of Brazil

- Mammals of Chile

- Mammals of Argentina

- Mammals of Peru

- Mammals of Bolivia

- Fauna of Trinidad and Tobago

- Mammals of Guyana

- Desmodus

- Mammals of Costa Rica

- Animals described in 1810

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

Look at other dictionaries:

common vampire bat — paprastasis vampyras statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Desmodus rotundus angl. blood sucking bat; common vampire bat; South American vampire bat; true vampire; vampire; vampire bat vok. echter Vampir;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

Vampire bat — For the 1933 movie, see The Vampire Bat. Vampire bats Common Vampire Bat, Desmodus rotundus Scientific classification Kingdom … Wikipedia

vampire bat — 1. any of several New World tropical bats of the genera Desmodus, Diphylla, and Diaemus, the size of a small mouse, feeding on small amounts of blood obtained from resting mammals and birds by means of a shallow cut made with specialized incisor… … Universalium

vampire bat — paprastasis vampyras statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Desmodus rotundus angl. blood sucking bat; common vampire bat; South American vampire bat; true vampire; vampire; vampire bat vok. echter Vampir;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

White-winged Vampire Bat — Diaemus youngi Conservation status … Wikipedia

Hairy-legged Vampire Bat — Conservation status Least Concern ( … Wikipedia

South American vampire bat — paprastasis vampyras statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Desmodus rotundus angl. blood sucking bat; common vampire bat; South American vampire bat; true vampire; vampire; vampire bat vok. echter Vampir;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

Common Big-eared Bat — Conservation status Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) Scientific classification K … Wikipedia

Bat — For other uses, see Bat (disambiguation). Bats Temporal range: 52–0 Ma … Wikipedia

vampire — paprastasis vampyras statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Desmodus rotundus angl. blood sucking bat; common vampire bat; South American vampire bat; true vampire; vampire; vampire bat vok. echter Vampir;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas