- Chinese influences on Islamic pottery

-

Left image: Chinese-made sancai shard, 9-10th century, found in Samarra. British Museum.

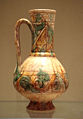

Right image: Iraqi earthen jar, 9th century, derived from Tang export wares. British Museum.Chinese influences on Islamic pottery cover a period starting from at least the 8th century CE to the 19th century.[1][2] This influence of Chinese ceramics has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.[3]

Contents

Earliest exchanges

Early contacts with Central Asia

Despite the distances involved, there is evidence of some contact between eastern and southwestern Asia from antiquity. Some very early Western influence on Chinese pottery seems to appear from the 3rd-4th century BCE. An Eastern Zhou red earthenware bowl, decorated with slip and inlaid with glass paste, and now in the British Museum, is thought to have imitated metallic vessels, possibly of foreign origin. Foreign influence especially is thought to have encouraged the Eastern Zhou interest in glass decorations.[4]

Left image: Northern Qi jar with Central Asian, possibly Sogdian, dancer and musicians, 550-577.[5]

Middle image: Earthenware jar with Central Asian face, Northern Qi 550-577.

Right image: Northern Qi earthenware with multicultural (Egyptian, Greek, Eurasian) motifs, 550-577.[6]Contacts between China and Central Asia were formally opened from the 2nd to 1st century BCE through the Silk Road.[6] In the following centuries, a great cultural influx benefited China, embodied by the appearance in China of foreign art, new ideas and religions (especially Buddhism), and new lifestyles.[6] Artistic influences combined a multiplicity of cultures which had intermixed along the Silk Road, especially Hellenistic, Egyptian, Indian and Central Asian cultures, displaying a strong cosmopolitanism.[5][6]

Such mixed influences are especially visible in the earthenwares of Northern China in the 6th century, such as those of the Northern Qi (550-577) or the Northern Zhou (557-581).[5][6] In that period, high quality high-fired earthenware starts to appear, called the "jeweled type", which incorporates lotuses from Buddhist art, as well as elements of Sasanian designs such as pearl roundels, lion masks or musicians and dancers.[5] The best of these ceramics use bluish green, yellow or olive glazes.[5]

China and the Islamic world

Tang Dynasty earthenware fragment with sancai glaze, end of 7th-early 8th century, excavated in Nishapur, Iran.

Tang Dynasty earthenware fragment with sancai glaze, end of 7th-early 8th century, excavated in Nishapur, Iran.

Direct contacts between the Muslim and Chinese worlds were marked by the Battle of Talas in 751 in Central Asia. Muslim communities are known to have been present in China as early as the 8th century CE, especially in commercial harbours such as Canton and Hangzhou.[3]

From the 9th century onwards, Islamic merchants started to import Chinese ceramics, which were at the core of the Indian Ocean luxury trade at that time.[2][3] These exotic objects were cherished in the Islamic world and also became an inspiration for local potters.[2][3]

Archaeological finds of Chinese pottery in the Middle East go back to the 8th century, starting with Chinese pottery of the Tang period (618-907).[1][7] Remains of Tang period (618-907) ceramics have been found in Samarra and Ctesiphon in present-day Iraq, as well as in Nishapur in present-day Iran.[6] These include porcelaneous white wares from Northern Chinese kilns, celadon-glazed stoneware originating in the Yue kilns of Northern Zhejiang, and the splashed stoneware of Changsha kilns in Hunan Province.[6][7]

Chinese pottery was the object of gift-making in Islamic lands: the Islamic writer Muhammad Ibn-al-Husain-Bahaki wrote in 1059 that Ali Ibn Isa, the governor of Khurasan, presented Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph, twenty pieces of Chinese imperial porcelain, the like of which had never been at a caliph's court before, in addition to 2,000 other pieces of porcelain".[1]

Evolution

Yue ware

Further information: Yue wareYue ware originated in the Yue kilns of Northern Zhejiang, in the site of Jiyuan near Shaoxing, anciently called "Yuezhou" (越州).[6][8] Yue ware was first manufactured from the 2nd century CE, when it consisted in some very precise imitations of bronze vessels, many of which were found in tombs of the Nanjing region.[8] After this initial phase, Yue ware evolved progressively into true ceramic form, and became a true medium of artistic expression.[8][9] Production in Jiyuan stopped in the 6th century, but expanded to various areas of Zhejiang, especially around the shores of Shanglinhu in Yuyaoxian.[8][9]

Yue ware was highly valued, and was used as tribute for the imperial court in northern China in the 9th century.[9] Significantly, it was also used in China's most revered Famen Temple in Shaanxi Province.[9] Yue ware was exported to the Middle East early on, and shards of Yue ware have been excavated in Samarra, Iraq, in an early example of Chinese influences on Islamic pottery,[6] as well as to East Asia and South Asia as well as East Africa from the 8th to the 11th century.[9]

Sancai ware

Further information: SancaiLeft image: Chinese Tang lobed dish 9-10th century. British Museum.

Right image: Iraqi lobed dish inspired from Tang examples, 9-10th century. British Museum.Tang period earthenware shards with low-fired polychrome three-color sancai glazes from the 9th century were exported to Middle-Eastern countries such as Iraq and Egypt, and have been excavated in Samarra in present-day Iraq and in Nishapur in present-day Iran.[6][10] These Chinese styles were soon adopted for local Middle-Eastern manufactures. Copies were made by Iraqi craftsmen as soon as the 9th century CE.[3][11]

In order to imitate Chinese Sancai, lead glazes were used on top of vessels coated with white slip and a colorless glaze. The coloured lead glazes were then splashed on the surface, where they spread and mixed, according to the slipware technique.[2]

Shapes were also imitated, such as the lobed dishes found in Chinese Tang ceramics and silverware which were reproduced in Iraq during the 9-10th century.[3]

Conversely, numerous Central Asian and Persian influences were at work in the designs of Chinese sancai wares: pictures of Central Asian mounted warriors, scenes representing Central Asian musicians, vases in the shape of Middle-Eastern ewers.

White ware

Further information: Tin-glazed pottery Chinese white ware bowl found in Iran (left), and Iraqi earthenware bowl (right), both 9-10th century. British Museum.

Chinese white ware bowl found in Iran (left), and Iraqi earthenware bowl (right), both 9-10th century. British Museum.

Soon after the sancai period, Chinese white ware ceramics also found their way to the Islamic world,[7][10] and were immediately reproduced.[3] The Chinese white ware was actually porcelain, invented in the 9th century, and used kaolin and high-temperature firing,[2] but Islamic workshops were unable to duplicate its manufacture. Instead, they manufactured fine earthenware bowls with the desired shape, and covered them with a white glaze rendered opaque by the addition of tin, an early example of tin-glazing.[2][3][11] The Chinese shapes were also reproduced, seemingly to pass for China-made wares.[2]

In the 12th century, Islamic manufacturers further developed stone-paste techniques in order to obtain hard bodies approximating the hardness obtained by Chinese porcelain. This technique was used until the 18th century, when the Europeans discovered the Chinese technique for high-firing porcelain clays.[2][3]

Celadon ware

The Chinese fashion for turquoise, or celadon, ware was also transmitted to the Islamic world, where it gave rise to productions using turquoise glazing and fish motifs identical to the ones used in China.[3]

Blue and white ware

Further information: Blue and white porcelain and İznik potteryLeft image: Ming plate with grape design, 15th century, Jingdezhen kilns, Jiangxi. British Museum.

Right image: Stone-paste dish with grape design, Iznik, Turkey, 1550-70. British Museum.The technique of cobalt blue decorations seems to have been invented in the Middle East in the 9th century through decorative experimentation on white ware,[2] and the technique of blue-and-white ware was developed in China in the 14th century.[12][2] On some occasions, Chinese blue and white wares also incorporated Islamic designs, as in the case of some Mamluk brass works which were converted into blue and white Chinese porcelain designs.[3] Chinese blue and white ware then became extremely popular in the Middle East, where both Chinese and Islamic types coexisted.[2]

From the 13th century, Chinese pictorial designs, such as flying cranes, dragons and lotus flowers also started to appear in the ceramic productions of the Near East, especially in Syria and Egypt.[3]

An example of reverse influence, with the adoption of an Islamic design in Chinese porcelain.

Left image: Brass tray stand, Egypt or Syria, in the name of Muhammad ibn Qalaun, 1330-40.British Museum.

Right image: Ming porcelain tray stand with pseudo-arabic letters, 15th century, found in Damascus. British Museum. Ming Dynasty incense burner (1575-1600) with Ottoman metallic mount dated 1618. Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.

Ming Dynasty incense burner (1575-1600) with Ottoman metallic mount dated 1618. Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.

Chinese porcelain of the 14th or 15th century was transmitted to the Middle East and the Near East, and especially to the Ottoman Empire either through gifts or through war booty. Chinese designs were extremely influential with the pottery manufacturers at Iznik, Turkey. The Ming "grape" design in particular was highly popular and was extensively reproduced under the Ottoman Empire.[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Studies in Chinese ceramics by Dekun Zheng, Cheng Te-K'Un p.90ff [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Medieval Islamic civilization: an encyclopedia by Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach p.143 [2]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Notice of British Museum "Islamic Art Room" permanent exhibit.

- ^ British Museum, Ancient China permanent exhibit

- ^ a b c d e The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.119ff

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Notice of the Metropolitan Museum of Art permanent exhibition.

- ^ a b c Maritime silk road Qingxin Li p.68

- ^ a b c d The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.90ff

- ^ a b c d e Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.35ff [3]

- ^ a b Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.205ff [4]

- ^ a b Islamic art by Barbara Brend p.41

- ^ Porcelain. Columbia Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Rawson, Jessica, Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon, British Museum Publications Ltd, London, 1984, ISBN 9780714114316

Porcelain China Chinese porcelain · Chinese export porcelain · Chinese influences on Islamic pottery

Types: Proto-celadon (16th century BCE) · Celadon (1st century) · Yue (2nd century) · Jingdezhen (6th century) · Sancai (8th century) · Ding (10th century) · Qingbai (12th century) · Blue and white (14th century) · Blanc de Chine (14th century) · Kraak (16th century) · Swatow (16th century) · Kangxi (17th century) · Famille jaune, noire, rose, verte (17th century) · Tenkei (17th century) · Canton (18th century)Korea Types: Joseon (14th century)Japan Europe French porcelain · Chinese porcelain in European painting

Types: Fonthill Vase (1338) · Medici (1575) · Rouen (1673) · Nevers · Saint-Cloud (1693) · Meissen (1710) · Chantilly (1730) · Vincennes (1740) · Chelsea (1743) · Oranienbaum (1744) · Mennecy (1745) · Bow (1747) · Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory (1747) · Plymouth (1748) · Worcester (1751) · Frankenthal Porcelain Factory (1755) · Sèvres (1756) · Derby (1757) · Wedgwood (1759) · Wallendorf (1764) · Etiolles (1770) · Limoges (1771) · Clignancourt (1775) · Royal Copenhagen (1775) · Revol (1789) · Herend Porcelain Manufactory (1826) · Zsolnay (1853)Technologies People Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus · Johann Friedrich Böttger · Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles · Dmitry VinogradovCollections British Museum (London): Asia Department / Percival David Foundation · Dresden Porcelain Collection · Gardiner Museum (Toronto) · Kuskovo State Museum of Ceramics (Moscow) · Musée national de Céramique-Sèvres (Paris) · Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) · Palace Museum (Beijing) · Topkapı Palace (Istanbul) · Victoria and Albert Museum (London) · Worcester Porcelain MuseumCategories:- History of ceramics

- Chinese porcelain

- Islamic art

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.