- Pseudospark switch

-

The pseudospark switch, also known as a cold-cathode thyratron due to the similarities with regular thyratrons, is a gas-filled tube capable of high speed switching. Advantages of pseudospark switches include the ability to carry reverse currents (up to 100%), low pulse, high lifetime, and a high current rise of about 1012 A/sec. In addition, since the cathode is not heated prior to switching, the standby power is approximately one order of magnitude lower than in thyratrons. However, pseudospark switches have undesired plasma phenomena at low peak currents. Issues such as current quenching, chopping, and impedance fluctuations occur at currents less than 2-3 kA while at very high peak currents (20-30 kA) a transition to a metal vapor arc occurs which leads to erosion of the electrodes.[1] Pseudospark switches are functionally similar to triggered spark gaps.

Contents

Construction

A pseudospark switch's electrodes (cathode and anode) have central holes approximately 3 to 5 mm in diameter. Behind the cathode and anode lie a hollow cathode and hollow anode, respectively. The electrodes are separated by an insulator. A low pressure (less than 50 Pa) "working gas" (typically hydrogen) is contained between the electrodes.[1]

While a pseudospark switch is generally fairly simple in construction, engineering a switch for higher lifetimes is more difficult. One method of extending the lifetime is to create a multichannel pseudospark switch to distribute the current and as a result, decrease the erosion. Another method is to simply use cathode materials more resistant to erosion.[1]

Typical electrode materials include copper, nickel, tungsten/rhenium, molybdenum, tantalum, and ceramic materials. Tantalum, however, cannot be used with hydrogen due to chemical erosion affecting the lifetime adversely.[2] Of the metals, tungsten and molybdenum are commonly used, though molybdenum electrodes show issues with reignition behavior.[1] Several papers which compare electrode materials claim tungsten is the most suitable of the metal electrodes tested.[2] Some ceramic materials such as silicon carbide and boron carbide have proven to be excellent electrode materials as well, with lower erosion rates than tungsten in certain cases.[3][4]

The Pseudospark Discharge

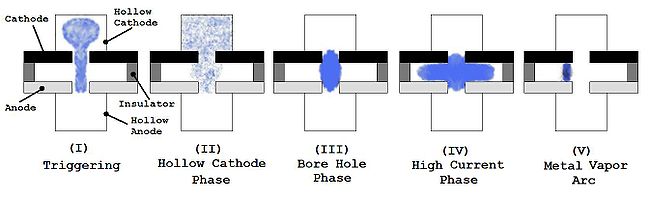

In a pseudospark discharge a breakdown is first triggered between the electrodes by applying a voltage. The gas then breaks down as a function of the pressure, distance, and voltage. An "ionization avalanche" then occurs producing a homogeneous discharge plasma confined to the central regions of the electrodes.[1]

In the figure above, the various stages of the pseudospark discharge can be seen. Stage (I) is the triggering or low current phase. The discharges in both stage (II), the hollow cathode phase, and stage (III), the borehole phase, are capable of carrying currents of several hundred amps. The transition from the borehole phase to the high current phase (IV) is very fast, characterized by a sudden jump in switch impedance. The last phase (V) only occurs for currents of several 10 kA and is unwelcome as it results in high erosion rates.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Urban, Jurgen; Klaus Frank (2002). "Cold Cathode Thyratron Development for Pulsed Power Applications". Power Modulator Symposium, 2002 and 2002 High-Voltage Workshop. Conference Record of the Twenty-Fifth International: 217–220. ISBN 0-7803-7540-8. ISSN 1076-8467. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&isnumber=&arnumber=1189455.

- ^ a b Prucker, U. (1998). "Electrode Erosion of High-Current Pseudospark Switches". Discharges and Electrical Insulation in Vacuum, 1998. Proceedings ISDEIV. XVIIIth International Symposium on 1: 398–401. doi:10.1109/DEIV.1998.740653. ISBN 0-7803-3953-3. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/freeabs_all.jsp?arnumber=740653.

- ^ Weisser, Wolfgang; Klaus Frank (2001). "Silicon Carbide as Electrode Material of a Pseudospark Switch". Plasma Science, IEEE Transactions on 29 (3): 524–528. Bibcode 2001ITPS...29..524W. doi:10.1109/27.928951. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/Xplore/login.jsp?url=http%3A%2F%2Fieeexplore.ieee.org%2Fiel5%2F27%2F20083%2F00928951.pdf%3Farnumber%3D928951&authDecision=-203.

- ^ Schwandner, A.; J. Christiansen, K. Frank, D.H.H. Hoffmann, U. Prucker (1996). "Investigations of Carbide Electrodes in High-Current Pseudospark Switches". Discharges and Electrical Insulation in Vacuum, 1996. Proceedings. ISDEIV., XVIIth International Symposium on 2 (21–26): 1014–1017. doi:10.1109/DEIV.1996.545519. ISBN 0-7803-2906-6. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/Xplore/login.jsp?url=http%3A%2F%2Fieeexplore.ieee.org%2Fiel3%2F3851%2F11243%2F00545519.pdf%3Farnumber%3D545519&authDecision=-203.

- Christiansen, J.; Schultheiss, C. (1979). "Production of high current particle beams by low pressure spark discharges". Zeitschrift für Physik A 290: 35–41. Bibcode 1979ZPhyA.290...35C. doi:10.1007/bf01408477.

- Bochkov V. (2009). "SN-Series Pseudospark Switches Operating Completely Without Permanent Heating. New Prospects of Application". Acta Physica Polonica A 115: 980–982.

- Bochkov V. (2009). "Prospective Pulsed Power Applications Of Pseudospark Switches". Proc. 17th IEEE International Pulsed Power Conference 1: 255–259.

External links

Categories:- Gas-filled tubes

- Switching tubes

- Plasma physics

- Electrical breakdown

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.