- New Spain

-

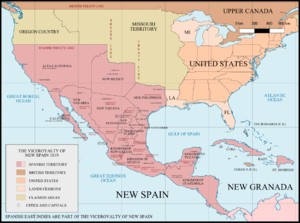

New Spain, formally called the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish: Virreinato de Nueva España), was a viceroyalty of the Spanish colonial empire, comprising primarily territories in what was known then as 'América Septentrional' or North America.[1][2][3][4] Its capital was Mexico City, formerly Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire. New Spain was established following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521, and at its greatest extent included much of North America south of Canada: all of present-day Mexico and Central America (except Panama), most of the United States west of the Mississippi River and the Floridas.

New Spain also included the Spanish East Indies (Philippine Islands, Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, Taiwan, and parts of the Moluccas) and the Spanish West Indies (Cuba, Hispaniola with Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Trinidad, and the Bay Islands).

Administrative units included Las Californias (present-day California, Nevada, Baja California, and Baja California Sur), Nueva Extremadura (including the present-day states of Coahuila and Texas), and Santa Fe de Nuevo México (including parts of Texas and New Mexico).[5]

New Spain was the first of four viceroyalties created to govern Spain's foreign colonies. New Spain was ruled by a viceroy in Mexico City who governed the various territories of New Spain on behalf of the King of Spain. The Viceroyalty of Peru was created in 1542 following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. In the 18th century the Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada, and the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata were also created.

Contents

History

Establishment (1521–1535)

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Cross of Burgundy served as the flag of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and Peru at sea, and in forts. The Royal Standard of Spain was used for all other purposes.

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Cross of Burgundy served as the flag of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and Peru at sea, and in forts. The Royal Standard of Spain was used for all other purposes.

The creation of a viceroyalty in the Americas was a result of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519 to 1521). The lands and societies brought under Spanish control were of unprecedented complexity and wealth, which presented both an incredible opportunity and a threat to the Crown of Castile. The societies could provide the conquistadors, especially Hernán Cortés, a base from which to become autonomous, or even independent, of the Crown. As a result the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V created the Council of the Indies in 1524.

A few years later the first mainland Audiencia was created in 1527 to take over the administration of New Spain from Hernán Cortés. An earlier Audiencia had been established in Santo Domingo in 1526 to deal with the Caribbean settlements. The Audiencia, housed in the Casa Reales in Santo Domingo, was charged with encouraging further exploration and settlements under its own authority. Management by the Audiencia, which was expected to make executive decisions as a body, proved unwieldy.

Therefore in 1535, King Charles V named Antonio de Mendoza as the first Viceroy of New Spain. After the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 opened up the vast territories of South America to further conquests, the Crown established an independent Viceroyalty of Peru there in 1540.

Exploration and Settlement (1519–1643)

"Vázquez de Coronado Sets Out to the North" (1540) by Frederic Remington, oil on canvas, 1905

"Vázquez de Coronado Sets Out to the North" (1540) by Frederic Remington, oil on canvas, 1905 Main article: Spanish colonization of America

Main article: Spanish colonization of AmericaUpon his arrival, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza vigorously took to the duties entrusted to him by the King and encouraged the exploration of Spain's new mainland territories. He commissioned the expeditions of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado into the present day American Southwest in 1540–1542. The Viceroy commissioned Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in the first Spanish exploration up the Pacific Ocean along the western coast of the Las Californias Province in 1542–1543. He sailed above present day Baja California (Vieja California), to what he called 'New California' (Nueva California), becoming the first European to see present day California, U.S. The Viceroy also sent Ruy López de Villalobos to the Spanish East Indies in 1542–1543. As these new territories became controlled, they were brought under the purview of the Viceroy of New Spain.

During the 16th century, many Spanish cities were established in North and Central America. Spain attempted to establish missions in what is now the Southern United States including Georgia and South Carolina between 1568 and 1587. Despite their efforts, the Spaniards were only successful in the region of present day Florida, where they founded St. Augustine in 1565.

Seeking to develop trade between the East Indies and the Americas across the Pacific Ocean, Miguel López de Legazpi established the first Spanish settlement in the Philippine Islands in 1565, which became the town of San Miguel. Andrés de Urdaneta discovered an efficient sailing route from the Philippine Islands returning to Mexico. In 1571, the city of Manila became the capital of the Spanish East Indies, with trade soon beginning via the Manila-Acapulco Galleons. The Manila-Acapulco trade route shipped products such as silks, spices, silver, and gold, and enslaved people to the Americas from Asia.

Products brought from East Asia were sent to Veracruz México, then shipped to Spain, and then traded across Europe. There were attacks on these shipments in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea by British and Dutch pirates and privateers, led by Francis Drake in 1586, and Thomas Cavendish in 1587. In addition, the cities of Huatulco (Oaxaca) and Barra de Navidad in Jalisco Province of México were sacked. Lope Díez de Armendáriz was the first Viceroy of New Spain that was born in the 'New World' (Nueva España). He formed the 'Navy of Barlovento' (Armada de Barlovento), based in Veracruz, to patrol coastal regions and protect the harbors, port towns, and trade ships from pirates and privateers.

New Mexico

Luis de Velasco, marqués de Salinas gained control over many of the semi-nomadic Chichimeca indigenous tribes of northern México in 1591 for awhile. This allowed expansion into the 'Province of New Mexico' or Provincia de Nuevo México. In 1598, Juan de Oñate pioneered 'The Royal Road of the Interior Land' or El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro between Mexico City and the 12CE Tewa village of 'Ohkay Owingeh' or San Juan Pueblo. He also founded the settlement (a Spanish pueblo) of San Juan on the Rio Grande near the Native American Pueblo, located in the present day U.S. state of New Mexico. In 1609, Pedro de Peralta, a later governor of the Province of New Mexico, established the settlement of Santa Fe in the region of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the Rio Grande. Missions were established for conversions and agricultural industry. The territory's Puebloan peoples resented the Spaniards denigration and prohibition of their traditional religion, and their encomienda system's forced labor. The Pueblo Revolt ensued in 1680, with final resolution including some freedom from Spanish efforts to eradicate their culture and religion, the issuing of substantial communal land grants to each Pueblo, and a public defender of their rights and for their legal cases in Spanish courts. In 1776 the Province came under the new Provincias Internas jurisdiction. In the late 18th century the Spanish land grant encouraged the settlement by individuals of large land parcels outside Mission and Pueblo boundaries, many of which became ranchos.[6]

California

In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno, the first Spanish presence in the 'New California' or Nueva California region of the frontier Las Californias Province since Cabrillo in 1542, sailed as far upcoast north as Monterey Bay. In 1767 King Charles III ordered the Jesuits, who had established missions in the lower Baja California region of Las Californias, forcibly expelled and returned to Spain.[15] New Spain's Visitador General José de Gálvez replaced them with the Dominican Order in Baja, and the Franciscans to establish the new northern missions. In 1768, Visitador General José de Gálvez received the following orders: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." The Spanish colonization there, with far fewer recognized natural resources and less cultural development than Mexico or Peru, was to combine establishing a presence for defense of the territory with a perceived responsibility to convert the indigenous people to Christianity. The method was the traditional missions (misiones), forts (presidios), civilian towns (pueblos), and land grant ranches (ranchos) model, but more simplified due to the region's great distance from supplies and support in México. Between 1769 and 1833 twenty one Spanish missions in California were established. In 1776 the Province came under the administration of the new 'Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North' (Provincias Internas) to invigorate growth. The crown created two new governments in Las Californias, the southern peninsular one called Baja California, and the northern mainland one called Alta California in 1804. The issuing of Spanish land grants in California encouraged settlement and establishment of large California ranchos. Some Californio rancho grantees emulated the Dons of Spain, with cattle and sheep marking wealth. The work was usually done by displaced and relocated Native Americans. After the Mexican War of Independence and subsequent secularization ("disestablishment") of mission lands, Mexican land grant transactions increased the spread of ranchos. The land grants and ranchos established land-use patterns that are recognizable in present day California and New Mexico.[6]

The last Spanish Habsburgs (1643–1713)

The Presidios (forts), pueblos (civilian towns) and the misiones (missions) were the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial holdings in these territories.

The town of Alburquerque (present day Albuquerque, New Mexico) was founded in 1706. The Mexican towns of: Paso del Norte (present day Ciudad Juárez) founded in 1667; Santiago de la Monclova in 1689; Panzacola, Tejas in 1681; and San Francisco de Cuéllar (present day city of Chihuahua) in 1709. From 1687, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, with the marqués de Villapuente's economic help, founded over twenty missions in the Sonoran Desert (in present day Mexican state Sonora and U.S. state Arizona). From 1697, Jesuits established eighteen missions throughout the Baja California Peninsula. In 1668 Padre San Vitores established the first mission in the Mariana Islands (now Guam). Between 1687 and 1700 several Missions were founded in Trinidad, but only four survived as Amerindian villages throughout the 18th century. In 1691, explorers and missionaries visited the interior of Texas and came upon a river and Amerindian settlement on June 13, the feast day of St. Anthony, and named the location and river San Antonio in his honor.

Immersed in a low intensity war with Great Britain (mostly over the Spanish ports and trade routes harassed by British pirates), the defenses of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa, Jamaica, Cuba and Florida were strengthened. Santiago de Cuba (1662), St. Augustine Spanish Florida (1665) or Campeche 1678 were sacked by the British. The Tarahumara Indians were in revolt in the mountains of Chihuahua for several years. In 1670 Chichimecas invaded Durango, and the governor, Francisco González, abandoned its defense. In 1680, 25,000 previously subjugated Indians in 24 pueblos of New Mexico rose against the Spanish and killed all the Europeans they encountered. In 1685, after a revolt of the Chamorros, the Marianas islands were incorporated to the Captaincy General of the Philippines. In 1695, this time with the British help, the viceroy Gaspar de la Cerda attacked the French who had established a base on the island of Española[disambiguation needed

].

].Early in the Queen Anne's War, in 1702, the English captured and burned the Spanish town St. Augustine, Florida. However, the English were unable to take the main fortress (presidio) of St. Augustine, resulting in the campaign being condemned by the English as a failure. The Spanish maintained St. Augustine and Pensacola for more than a century after the war, but their mission system in Florida was destroyed and the Apalachee tribe was decimated in what became known as the Apalachee Massacre of 1704. Also in 1704 the viceroy Francisco Fernández de la Cueva suppressed a rebellion of the Pima Indians in Nueva Vizcaya.

Diego Osorio de Escobar y Llamas reformed the postal service and the marketing of mercury. In 1701 under the Duke of Alburquerque the 'Court of the Agreement' (Tribunal de la Acordada), an organization of volunteers, similar to the 'Holy Brotherhood' (Hermandad), intended to capture and quickly try bandits, was founded. The church of the Virgin of Guadalupe, patron of Mexico, was finished in 1702.

The Bourbon Reforms (1713–1806)

Main article: Bourbon ReformsThe new Bourbon kings did not split the Viceroyalty of New Spain into smaller administrative units as they did with the Viceroyalty of Peru. The first innovation, in 1776, was by José de Gálvez, the new Minister of the Indies (1775–1787), establishing the Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas known as the Provincias Internas (Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North, (Spanish: Comandancia y Capitanía General de las Provincias Internas). He appointed Teodoro de Croix (nephew of the former viceroy) as the first Commander General of the Provinicas Internas, independent of the Viceroy of New Spain, to provide more autonomy for the frontier provinces. They included Nueva Vizcaya, Nuevo Santander, Sonora y Sinaloa, Las Californias, Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas), and Nuevo México.

The prime innovation introduction of intendancies, an institution borrowed from France. They were first introduced on a large scale in New Spain, by the Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez, in the 1770s, who originally envisioned that they would replace the viceregal system (viceroyalty) altogether. With broad powers over tax collection and the public treasury and with a mandate to help foster economic growth over their districts, intendants encroached on the traditional powers of viceroys, governors and local officials, such as the corregidores, which were phased out as intendancies were established. The Crown saw the intendants as a check on these other officers. Over time accommodations were made. For example, after a period of experimentation in which an independent intendant was assigned to Mexico City, the office was thereafter given to the same person who simultaneously held the post of viceroy. Nevertheless, the creation of scores of autonomous intendancies throughout the Viceroyalty, created a great deal of decentralization, and in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, in particular, the intendancy laid the groundwork for the future independent nations of the 19th century.

In 1780, Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez sent a royal dispatch to Teodoro de Croix, Commandant General of the Internal Provinces of New Spain (Provincias Internas), asking all subjects to donate money to help the American Revolution. Millions of pesos were given.

The focus on the economy (and the revenues it provided to the royal coffers) was also extended to society at large. Economic associations were promoted, such as the Economic Society of Friends of the Country Governor-General José Basco y Vargas established in the Philippines in 1781. Similar "Friends of the Country" economic societies were established throughout the Spanish world, including Cuba and Guatemala.[7]

A secondary feature of the Bourbon Reforms was that it was an attempt to end the significant amount of local control that had crept into the bureaucracy under the Habsburgs, especially through the sale of offices. The Bourbons sought a return to the monarchical ideal of having outsiders, who in theory should be disinterested, staff the higher echelons of regional government. In practice this meant that there was a concerted effort to appoint mostly peninsulares, usually military men with long records of service (as opposed to the Habsburg preference for prelates), who were willing to move around the global empire. The intendancies were one new office that could be staffed with peninsulares, but throughout the 18th century significant gains were made in the numbers of governors-captain generals, audiencia judges and bishops, in addition to other posts, who were Spanish-born.

18th century military conflicts

See also: Louisiana (New Spain)The first century that saw the Bourbons on the Spanish throne coincided with series of global conflicts that pitted primarily France against Great Britain. Spain as an ally of Bourbon France was drawn into these conflicts. In fact part of the motivation for the Bourbon Reforms was the perceived need to prepare the empire administratively, economically and militarily for what was the next expected war. The Seven Years' War proved to be catalyst for most of the reforms in the overseas possessions, just like the War of the Spanish Succession had been for the reforms on the Peninsula.

In 1720, the Villasur expedition from Santa Fe met and attempted to parley with French- allied Pawnee in what is now Nebraska. Negotiations were unsuccessful, and a battle ensued; the Spanish were badly defeated, with only thirteen managing to return to New Mexico. Although this was a small engagement, it is significant in that it was the deepest penetration of the Spanish into the Great Plains, establishing the limit to Spanish expansion and influence there.

The War of Jenkins' Ear broke out in 1739 between the Spanish and British and was confined to the Caribbean and Georgia. The major action in the War of Jenkins' Ear was a major amphibious attack launched by the British under Admiral Edward Vernon in March, 1741 against Cartagena de Indias, one of Spain's major gold-trading ports in the Caribbean (today Colombia). Although this episode is largely forgotten, it ended in a decisive victory for Spain, who managed to prolong its control of the Caribbean and indeed secure the Spanish Main until the 19th century.

Following the French and Indian War/Seven Years War, the British troops invaded and captured the Spanish cities of Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines in 1762. The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Spain control over the New France Louisiana Territory including New Orleans, Louisiana creating a Spanish empire that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, but Spain also ceded Florida to Great Britain to regain Cuba, which the British occupied during the war. Louisiana settlers, hoping to restore the territory to France, in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768 forced the Louisiana Governor Antonio de Ulloa to flee to Spain. The rebellion was crushed in 1769 by the next governor Alejandro O'Reilly who executed five of the conspirators. The Louisiana territory was to be administered by superiors in Cuba with a governor onsite in New Orleans.

The 21 northern missions in present-day California (U.S.) were established along California's El Camino Real from 1769. In an effort to exclude Britain and Russia from the eastern Pacific, King Charles III of Spain sent forth from Mexico a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793. Spain's long-held claims and navigation rights were strengthened and a settlement and fort were built in Nootka Sound, Alaska.

A Spanish army defeats British soldiers in the Battle of Pensacola in 1781. In 1783 the Treaty of Paris returns all of Florida to Spain for the return of the Bahamas.

A Spanish army defeats British soldiers in the Battle of Pensacola in 1781. In 1783 the Treaty of Paris returns all of Florida to Spain for the return of the Bahamas.

Spain entered the American Revolutionary War as an ally of France in June 1779, a renewal of the Bourbon Family Compact. In 1781, a Spanish expedition during the American Revolutionary War left St. Louis, Missouri (then under Spanish control) and reached as far as Fort St. Joseph at Niles, Michigan where they captured the fort while the British were away. On 8 May 1782, Count Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, captured the British naval base at New Providence in the Bahamas. On the Gulf Coast, the actions of Gálvez led to Spain acquiring East and West Florida in the peace settlement, as well as controlling the mouth of the Mississippi River after the war—which would prove to be a major source of tension between Spain and the United States in the years to come.

In the second Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolution, Britain ceded West Florida back to Spain to regain The Bahamas, which Spain had occupied during the war. Spain then had control over the river south of 32°30' north latitude, and, in what is known as the Spanish Conspiracy, hoped to gain greater control of Louisiana and all of the west. These hopes ended when Spain was pressured into signing Pinckney's Treaty in 1795. France reacquired 'Louisiana' from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. The United States bought the territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

New Spain claimed the entire west coast of North America and therefore considered the Russian fur trading activity in Alaska, which began in the middle to late 18th century, an encroachment and threat. Likewise, the exploration of the northwest coast by James Cook of the British Navy and the subsequent fur trading activities by British ships was considered an invasion of Spanish territory. To protect and strengthen its claim, New Spain sent a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793. In 1789 a naval outpost called Santa Cruz de Nuca (or just Nuca) was established at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound (now Yuquot), Vancouver Island. It was protected by an artillery land battery called Fort San Miguel. Santa Cruz de Nuca was the northermost establishment of New Spain. It was the first colony in British Columbia and the only Spanish settlement in what is now Canada. Santa Cruz de Nuca remained under the control of New Spain until 1795, when it was abandoned under the terms of the third Nootka Convention. Another outpost, intended to replace Santa Cruz de Nuca, was partially built at Neah Bay on the southern side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in what is now the U.S. state of Washington. Neah Bay was known as Bahía de Núñez Gaona in New Spain, and the outpost there was referred to as "Fuca". It was abandoned, partially finished, in 1792. Its personnel, livestock, cannons, and ammunition were transferred to Nuca.[8]

In 1789, at Santa Cruz de Nuca, a conflict occurred between the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez and the British merchant James Colnett, triggering the Nootka Crisis, which grew into an international incident and the threat of war between Britain and Spain. The first Nootka Convention averted the war but left many specific issues unresolved. Both sides sought to define a northern boundary for New Spain. At Nootka Sound, the diplomatic representative of New Spain, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, proposed a boundary at the Strait of Juan de Fuca, but the British representative, George Vancouver refused to accept any boundary north of San Francisco. No agreement could be reached and the northern boundary of New Spain remained unspecified until the Adams–Onís Treaty with the United States (1819). That treaty also ceded Spanish Florida to the United States.

End of the Viceroyalty (1806–1821)

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso ceded to France the vast territory that Napoleon then sold to the United States, known as the Louisiana Purchase (1803). Spanish Florida followed in 1819. In the 1821 Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire, Mexico and Central America declared their independence after three centuries of Spanish rule and formed the First Mexican Empire. After priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's 1810 Grito de Dolores (call for independence), the insurgent army began an eleven-year war. At first, the Criollo class fought against the rebels. But in 1820, coinciding with the approval of the Spanish Constitution, which took privileges away from the Criollos, they switched sides. This led to Mexican triumph in 1821. The new Mexican Empire offered the crown to Ferdinand VII or to a member of the Spanish royal family that he would designate. After the refusal of the Spanish monarchy to recognize the independence of Mexico, the ejército Trigarante (Army of the Three Guarantees), led by Agustin de Iturbide and Vincente Guerrero, cut all political and economic ties with Spain and crowned Agustin I as emperor of Mexico. Central America was originally part of the Mexican Empire, but seceded peacefully in 1823, forming the United Provinces of Central America.

This left only Cuba, the Spanish East Indies (including the Philippines and Guam), and Puerto Rico in the Spanish empire until their loss to the United States in the Spanish–American War (1898).

Politics

History of Mexico

This article is part of a seriesPre-Columbian Mexico Spanish conquest Colonial period War of Independence First Empire First Republic War with Texas Pastry War Mexican–American War Second Federal Republic The Reform Reform War French intervention Second Empire Restored Republic The Porfiriato Revolution La decena trágica Plan of Guadalupe Tampico Affair Occupation of Veracruz Cristero War The Maximato Petroleum nationalization Mexican miracle Students of 1968 La Década Perdida 1982 economic crisis Zapatista Insurgency 1994 economic crisis Downfall of the PRI

Mexico Portal

The Viceroyalty of New Spain united many regions and provinces of the Spanish Empire throughout half a world. These included on the North American mainland, New Spain proper (central Mexico), Nueva Extremadura, Nueva Galicia, Nueva Vizcaya, and Nuevo Santander, as well as the Captaincy General of Guatemala. In the Caribbean it included Cuba, Santo Domingo, most of the Venezuelan mainland and the other islands in the Caribbean controlled by the Spanish. In Asia, the Viceroyalty ruled the Captaincy General of the Philippines, which covered all of the Spanish territories in the Asia-Pacific region. The outpost at Nootka Sound, on Vancouver Island, was considered part of the province of California.

Therefore, the Viceroyalty's former territories included what is now the present day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, Costa Rica; the United States regions of California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Puerto Rico, Guam, Mariana Islands, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Florida; a portion of the Canadian province of British Columbia; the Caribbean nations of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, the island of Hispaniola, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda; the Asia-Pacific nations of the Philippine Islands, Palau and Caroline Islands.

The Viceroyalty was administered by a viceroy residing in Mexico City and appointed by the Spanish monarch, who had administrative oversight of all of these regions, although most matters were handled by the local governmental bodies, which ruled the various regions of the viceroyalty. First among these were the audiencias, which were primarily superior tribunals, but which also had administrative and legislative functions. Each of these was responsible to the Viceroy of New Spain in administrative matters (though not in judicial ones), but they also answered directly to the Council of the Indies. Audiencia districts further incorporated the older, smaller divisions known as governorates (gobernaciones, roughly equivalent to provinces), which had been originally established by conquistador-governors known as adelantados. Provinces, which were under military threat, were grouped into captaincies general, such as the Captaincies General of the Philippines (established 1574) and Guatemala (established in 1609) mentioned above, which were joint military and political commands with a certain level of autonomy. (The viceroy was captain-general of those provinces that remained directly under his command).

At the local level there were over two hundred districts, in both Indian and Spanish areas, which were headed by either a corregidor (also known as an alcalde mayor) or a cabildo (town council), both of which had judicial and administrative powers. In the late 18th century the Bourbon dynasty began phasing out the corregidores and introduced intendants, whose broad fiscal powers cut into the authority of the viceroys, governors and cabildos. Despite their late creation, these intendancies had such an impact in the formation of regional identity that they became the basis for the nations of Central America and the first Mexican states after independence.

Audiencias

With dates of creation:

1. Santo Domingo (1511, effective 1526, predated the Viceroyalty)

2. Mexico (1527, predated the Viceroyalty)

3. Panama (1st one, 1538–1543)

4. Guatemala (1543)

5. Guadalajara (1548)

6. Manila (1583)Autonomous Captaincies General

With dates of creation:

1. Santo Domingo (1535)

2. Philippines (1574)

3. Puerto Rico (1580)

4. Cuba (1607)

5. Guatemala (1609)

6. Yucatán (1617)7. Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas (1776) (Analogous to a dependent captaincy general.)

Intendancies

Year of Creation[9][10] Intendancy 1764 Havana 1766 New Orleans 1784 Puerto Rico 1786 Mexico Chiapas Guatemala San Salvador Comayagua Léon Puerto Príncipe (separated from the Intendancy of Havana) Santiago de Cuba (separated from the Intendency of Havana) 1787 Guanajuato Valladolid Guadalajara Zacatecas San Luis Potosí Veracruz Puebla Oaxaca Durango Sonora 1789 Mérida Economy

In order to pay off the debts incurred by the conquistadors and their companies, the new Spanish governors awarded their men grants of native tribute and labor, known as encomiendas. In New Spain these grants were modeled after the tribute and corvee labor that the Mexica rulers had demanded from native communities. This system came to signify the oppression and exploitation of natives, although its originators may not have set out with such intent. In short order the upper echelons of patrons and priests in the society lived off the work of the lower classes. Due to some horrifying instances of abuse against the indigenous peoples, Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas suggested bringing black slaves to replace them. Fray Bartolomé later repented when he saw the even worse treatment given to the black slaves. The other discovery that perpetuated this system was extensive silver mines discovered at Potosi and other places that were worked for hundreds of years by forced native labor and contributed most of the wealth flowing to Spain. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was the principal source of income for Spain among the Spanish colonies, with important mining centers like Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo.

There were several major ports in New Spain. There were the ports of Veracruz the viceroyalty's principal port on the Atlantic, Acapulco on the Pacific, and Manila near the South China Sea. The ports were fundamental for overseas trade, stretching a trade route from Asia, through the Manila Galleon to the Spanish mainland.

These were ships that made voyages from the Philippines to Mexico, whose goods were then transported overland from Acapulco to Veracruz and later reshipped from Veracruz to Cádiz in Spain. So then, the ships that set sail from Veracruz were generally loaded with merchandise from the East Indies originating from the commercial centers of the Philippines, plus the precious metals and natural resources of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. During the 16th century, Spain held the equivalent of US$1.5 trillion (1990 terms) in gold and silver received from New Spain.

However, these resources did not translate into development for the Metropolis (mother country) due to Spanish Roman Catholic Monarchy's frequent preoccupation with European wars (enormous amounts of this wealth were spent hiring mercenaries to fight the Protestant Reformation), as well as the incessant decrease in overseas transportation caused by assaults from companies of British buccaneers, Dutch corsairs and pirates of various origin. These companies were initially financed by, at first, by the Amsterdam stock market, the first in history and whose origin is owed precisely to the need for funds to finance pirate expeditions, as later by the London market. The above is what some authors call the "historical process of the transfer of wealth from the south to the north."

Demographics

The role of epidemics

Spanish settlers brought to the American continent smallpox, typhoid fever, and other diseases. Most of the Spanish settlers had developed an immunity to these diseases from childhood, but the indigenous peoples lacked the needed antibodies since these diseases were totally alien to the native population at the time. There were at least three, separate, major epidemics that decimated the population: smallpox (1520 to 1521), measles (1545 to 1548) and typhus (1576 to 1581). In the course of the 16th century, the native population in Mexico went from an estimated pre-Columbian population of 8 to 20 million to less than two million. Therefore, at the start of the 17th century, continental New Spain was a depopulated country with abandoned cities and maize fields. These diseases would not have a similar impact in the Philippines because they were already present there.

The role of interracial mixing

Main article: CastaFollowing the Spanish conquests, new ethnic groups were created, primary among them the Mestizo. The Mestizo population emerged as a result of the Spanish colonizers having children with indigenous women, both within and outside of wedlock, which brought about the mixing of both cultures. Many of the Spanish colonists were either men or women with no wives or husbands and took partners from the indigenous population.

Initially, if a child was born in wedlock, the child was considered, and raised as, a member of the prominent parent's ethnicity. (See Hyperdescent and Hypodescent.) Because of this, the term "Mestizo" was associated with illegitimacy. Mestizos do not appear in large numbers in official censuses until the second half of the 17th century, when a sizable and stable community of mixed-race people with no claims to being either Indian or Spanish appeared, although, of course, a large population of biological Mestizos had already existed for over a century in Mexico.

The Spanish conquest also brought the migration of people of African descent to the many regions of the Viceroyalty. Some came as free blacks, but vast majority came because of the introduction of African slavery. As the native population was decimated by epidemics and forced labor, black slaves were imported. Mixes with Europeans and indigenous peoples also occurred, resulting in the creation of new racial categories such as Mulattos and Zambos to account for these offspring. As with the term Mestizo, these other terms were associated with illegitimacy, since a majority—though not all—of these people were born outside of wedlock.

Eventually a caste system was created to describe the various mixes and to assign them a different social level. In theory, each different mix had a name and different sets of privileges or prohibitions. In reality, mixed-race people were able to negotiate various racial and ethnic identities (often several ones at different points in their lives) depending on the family ties and wealth they had. In its general outline, the system reflected reality. The upper echelons of government were staffed by Spaniards born in Spain (peninsulares), the middle and lower levels of government and other higher paying jobs were held by Criollos (Criollos were "Spaniards" born in the Americas, or—as permitted by the casta system—"Spaniards" with some Amerindian or even other ancestry.[11]) The best lands were owned by Peninsulares and Criollos, with Native communities for the most part relegated to marginal lands. Mestizos and Mulattos held artisanal positions and unskilled laborers were either more mixed people, such as Zambos, recently freed slaves or Natives who had left their communities and settled in areas with large Hispanic populations. Native populations tended to have their own legally recognized communities (the repúblicas de indios) with their own social and economic hierarchies. This rough sketch must be complicated by the fact that not only did exceptions exist, but also that all these "racial" categories represented social conventions, as demonstrated by the fact that many persons were assigned a caste based on hyperdescent or hypodescent.

Even if mixes were common, the white population tried to keep their higher status, and were largely successful in doing so. With Mexican and Central American independence, the caste system and slavery were theoretically abolished. However, it can be argued that the Criollos simply replaced the Peninsulares in terms of power. Thus, for example, in modern Mexico, while Mestizos no longer have a separate legal status from other groups, they comprise approximately 65% of the population.[12] White people, who also no longer have a special legal status, are thought to be about 9–18% of the population,.[12] In modern Mexico, "Mestizo" has become more a cultural term, since Indigenous people who abandon their traditional ways are considered Mestizos. Also, most Afro-Mexicans prefer to be considered Mestizo, since they identify closely with this group. (See also, Demographics of Mexico.)

The population of New Spain in 1810

Population estimates from the first decade of the 19th century varied between 6,122,354 as calculated by Francisco Navarro y Noriega in 1810,[13] to 6.5 million as figured by Alexander von Humboldt in 1808.[14] Navarro y Noriega figured that half of his estimate constituted indigenous peoples. More recent data suggests that the actual population of New Spain in 1810 was closer to 5 or 5.5 million individuals.[15]

Culture

Because the Roman Catholic Church had played such an important role in the Reconquista (Christian reconquest) of the Iberian peninsula from the Moors, the Church in essence became another arm of the Spanish government. The Spanish Crown granted it a large role in the administration of the state, and this practice became even more pronounced in the New World, where prelates often assumed the role of government officials. In addition to the Church's explicit political role, the Catholic faith became a central part of Spanish identity after the conquest of last Muslim kingdom in the peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, and the expulsion of all Jews who did not convert to Christianity.

The conquistadors brought with them many missionaries to promulgate the Catholic religion. Amerindians were taught the Roman Catholic religion and the language of Spain. Initially, the missionaries hoped to create a large body of Amerindian priests, but this did not come to be. Moreover, efforts were made to keep the Amerindian cultural aspects which did not violate the Catholic traditions. As an example, some Spaniards learned some of the Amerindian languages (especially during the 16th century) and wrote grammars for them so that they could be more easily translated. This was similarly practiced by the French colonists.

At first, conversion seemed to be happening rapidly. The missionaries soon found that most of the natives had simply adopted "the god of the heavens", as they called the Christian god,[citation needed] as just another one of their many gods[citation needed]. While they often held the Christian god to be an important deity because it was the god of the victorious conquerors, they did not see the need to abandon their old beliefs. As a result, a second wave of missionaries began an effort to completely erase the old beliefs, which they associated with the ritualized human sacrifice found in many of the native religions, eventually putting an end to this practice common before the arrival of the Spaniards. In the process many artifacts of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture were destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of native codices were burned, native priests and teachers were persecuted, and the temples and statues of the old gods were torn down. Even some foods associated with the native religions, like amaranth, were forbidden.

Many clerics, such as Bartolomé de las Casas, also tried to protect the natives from de facto and actual enslavement to the settlers, and obtained from the Crown decrees and promises to protect native Mesoamericans, most notably the New Laws. Unfortunately, the royal government was too far to fully enforce them, and many abuses against the natives, even among the clergy, continued. Eventually, the Crown declared the natives to be legal minors and placed under the guardianship of the Crown, which was responsible for their indoctrination. It was this status that barred the native population from the priesthood. During the following centuries, under Spanish rule, a new culture developed that combined the customs and traditions of the indigenous peoples with that of Catholic Spain. Numerous churches and other buildings were constructed by native labor in the Spanish style, and cities were named after various saints or religious topics such as San Luis Potosí (after Saint Louis) and Vera Cruz (the True Cross).

The Spanish Inquisition, and its New Spanish counterpart, the Mexican Inquisition, continued to operate in the viceroyalty until Mexico declared its independence. During the seventeenth and 18th centuries, the Inquisition worked with the viceregal government to block the diffusion of liberal ideas during the Enlightenment and the revolutionary republican and democratic ideas of the United States War of Independence and the French Revolution.

Arts

The Viceroyalty of New Spain was one of the principal centers of European cultural expansion in the Americas. The viceroyalty was the basis for a racial and cultural mosaic of the Spanish American colonial period.

The first printing press in the New World was brought to Mexico in 1539, by printer Juan Pablos (Giovanni Paoli). The first book printed in Mexico was entitled La escala espiritual de San Juan Clímaco. In 1568, Bernal Díaz del Castillo finished La Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España. Figures such as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón stand out as some of the viceroyalty's most notable contributors to Spanish Literature. In 1693, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora published El Mercurio Volante, the first newspaper in New Spain.

Architects Pedro Martínez Vázquez and Lorenzo Rodriguez produced some fantastically extravagant and visually frenetic architecture known as Mexican Churrigueresque in the own capital, Ocotlan[disambiguation needed

], Puebla or remote silver-mining towns.

], Puebla or remote silver-mining towns.See also

- Colonialism

- List of Viceroys of New Spain

- List of Governors in the Viceroyalty of New Spain

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Spanish Empire

References

- ^ LANIC: Colección Juan Bautista Muñoz. Archivo de la Real Academia de la Historia – España. (in Spanish)

- ^ Selections from the National Library of Spain: Conquista del Reino de Nueva Galicia en la América Septrentrional..., Texas, Sonora, Sinaloa, con noticias de la California. (Conquest of the Kingdom of New Galicia in North America..., Texas, Sonora, Sinaloa, with news of California). (in Spanish)

- ^ Cervantes Virtual: Historia de la conquista de México (in Spanish)

- ^ Worldcat: Historia de la conquista de México, poblacion y progresos de la América Septentrional, conocida por el nombre de Nueva España (in Spanish)

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/412085/Viceroyalty-of-New-Spain

- ^ a b New Mexico Commission of Public Records, Land Grants, accessed 28 October 2009.

- ^ Shafer, Robert J. The Economic Societies in the Spanish World, 1763–1821. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1958.

- ^ Tovell, Freeman M. (2008). At the Far Reaches of Empire: The Life of Juan Francisco De La Bodega Y Quadra. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9780774813679. http://books.google.com/books?id=E8_LXicsIlEC.

- ^ Harding, C. H., The Spanish Empire in America. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1947), 133–135

- ^ Lombardi, Cathryn L., John V. Lombardi and K. Lynn Stoner, Latin American History: A Teaching Atlas. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 50. ISBN 0-299-09714-5

- ^ Carrera, Magali Marie (2003). Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 19–21. ISBN 0-292-71245-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=cgEYQ7LTkBQC.

- ^ a b "Mexico-People" CIA World Factbook, 2007. Retrieved on 2009-01-12.

- ^ (Spanish) Navarro y Noriega, Fernando (1820). Report on the population of the kingdom of New Spain.. Mexico: in the Office of D. Juan Bautista de Arizpe.

- ^ (French) Humboldt, Alexander von (1811). Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain. Paris: F. Schoell.

- ^ McCaa, Robert (1997-12-08). "The Peopling of Mexico from Origins to Revolution". The Population History of North America. Richard Steckel and Michael Haines (ed.). Cambridge University Press. http://www.hist.umn.edu/~rmccaa/mxpoprev/cambridg3.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

External links

- MEXICO'S COLONIAL ERA—PART I: The Settlement of New Spain at mexconnect.com

- Index to the DeWitt Colony Region under New Spain at Texas A&M University

- 1492 – Middle America at ibiblio.org the public's library and digital archive

- Encyclopedia Britannica : Hispanic Heritage in The Americas

Spanish missions Asia (Jesuit) · Arizona · Baja California · California · Carolinas · Florida · Georgia · Louisiana · Mexico · New Mexico · Sonoran Desert · South America · South America (Jesuit) · Texas · Trinidad · Virginia

Spanish Empire Administrative Institutions Viceroyalties Audiencias Captancies General Chile · Cuba · Guatemala · Spanish East Indies · Puerto Rico · Santo Domingo · Venezuela · Yucatán ˑ Provincias InternasGovernorates Viceroys of New Spain (1535-1821) Charles V (1535-1564)

Philip II (1566-1603) Gastón de Peralta · Martín Enríquez de Almanza · Lorenzo Suárez de Mendoza · Pedro Moya de Contreras · Álvaro Manrique de Zúñiga · Luis de Velasco · Gaspar de ZúñigaPhilip III (1603-1621) Philip IV (1621-1673) Diego Carrillo de Mendoza · Rodrigo Pacheco · Lope Díez de Armendáriz · Diego López Pacheco · Juan de Palafox y Mendoza · García Sarmiento de Sotomayor · Marcos de Torres y Rueda · Luis Enríquez de Guzmán · Francisco Fernández de la Cueva · Juan de Leyva de la Cerda · Diego Osorio de Escobar y Llamas · Antonio Sebastián de ToledoCharles II (1673-1701) Pedro Nuño Colón · Payo Enríquez de Rivera · Tomás de la Cerda · Melchor Portocarrero · Gaspar de la Cerda · Juan Ortega y Montañés · José Sarmiento y ValladaresPhilip V (1701-1746) Juan Ortega y Montañés · Francisco Fernández de la Cueva · Fernando de Alencastre · Baltasar de Zúñiga · Juan de Acuña · Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta · Pedro de Castro · Pedro Cebrián y AgustínFerdinand VI (1746-1760) Juan Francisco de Güemes · Agustín de Ahumada y VillalónCharles III (1760-1789) Charles IV (1789-1809) Ferdinand VII (1809-1821) Viceroyalties of the Spanish Empire Europe

America and East Indies  History of the Americas

History of the AmericasHistory North America · Mesoamerica · Central America · Caribbean · Latin America · South America · Genetics

Settlement Indigenous peoples · Indigenous population · Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact · Discovery · Exploration · European colonization · Spanish colonization · French colonization · Portuguese colonization · British colonization · Columbian Exchange · DecolonizationSocieties Related Lists Chronology Archaeology of the Americas · North America by period · North American timelines · Mesoamerica by period · Mesoamerica timelineEra: By period · By region · Three-age system · Ancient history · Pre-Columbian · Classical Antiquity · Middle Ages · Modern history · Future * – Article also discusses colonization in Central and South America and Asia Categories:- Former monarchies of North America

- Former countries in North America

- States and territories established in 1521

- States and territories disestablished in 1821

- New Spain

- Former Spanish colonies

- Spanish colonial period in the Philippines

- Viceroyalties of the Spanish Empire

- History of North America

- Colonial Mexico

- Colonial United States (Spanish)

- Colonization history of the United States

- Pre-state history of California

- Pre-state history of New Mexico

- Pre-state history of Arizona

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Spanish Texas

- States and territories established in 1519

- 1821 disestablishments

- Nobility of the Americas

- Latin American history

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.