- Coromantee people

-

Coromantee people, also called Coromantins or Coromanti people was the designation for recent Caribbean and South American people who were enslaved and brought from the Gold Coast or modern day Ghana. Coromantins were from several Akan ethnic groups – Ashanti, Fanti, Akyem, etc. – presumably taken as war captives. Owing to their militaristic background and common Akan language, Coromantins organized dozens of slave rebellions in Jamaica and the Caribbean. Their fierce, rebellious nature became so notorious amongst white plantation owners in the 18th century that an Act was proposed to ban the importation of people from the Gold Coast despite their reputation as strong workers. The Coromantins and other Akans had the single largest African cultural influence on Jamaica, including Jamaican Maroons whose culture and language was seen as a derivation of Akan. Names of some notable Coromantee leaders such as Cudjoe, Quamin, Cuffy, and Quamina correspond to Akan day names Kojo, Kwame, Kofi, and Kwabena, respectively.

Contents

History

Map of Ashanti Empire and the Gold Coast

Map of Ashanti Empire and the Gold Coast

Origin

In the 17th and 18th century, captive Africans from the Gold Coast area, modern day Ghana, were sent to Caribbean colonies. Jamaica received a high percentage of people from this region because of Great Britain’s control of the Gold Coast. These would have included people sold by the Ashanti, but because of frequent wars between Akan groups, would have also included Ashanti, Fanti, and other Akan prisoners of war. White slave owners began to distinguish Africans by place of origin and attach behaviors and characteristics based on their ethnicity.[1] “Coromantee” was defined as the country from where people came since they shared a common language today known as Twi, and this language formed the basis for membership in a loosely structured organization of people who socialized and helped one another. Edward Long, an 18th century white Jamaican colonist who strongly advocated banning Coromantins, noted that this unity amongst the Akan groups played an important role in organizing plots and rebellions despite the geographical dispersion of Coromantins across different plantations. The organizational unity of Coromantins, due to their common background also contributed to a mutual aid society, burial group, and places to enjoy social entertainment.[2]

Historical Culture

Prior to becoming enslaved Coromantins were usually part of highly organized and stratified Akan groups such as the Ashanti Empire. Akan states were not all the same, as there existed forty different groups in the mid-17th century, although they did share a common political language.[3] These groups also had shared mythology such as their being a single, powerful God, Nyame, and Anansi stories. These Anansi stories would be spread to the New World and became Annancy, Anansi Drew, or Br’er Rabbit stories in Jamaica, The Bahamas, and the Southern United States respectively. Akans also shared the concept of Day Names.[4] Evidence of this is seen in the names of several rebellion organizers such as Cuffy (Kofi), Cudjoe (Kojo), or Nanny (Nana) Bump.[5]

Slavery in Africa

One of the reasons for the rebellious nature of Coromantins may have been the stark differences between African slavery and American chattel slavery. Whereas in the Americas, where slaves were simply property not entitled to rights as people, African slavery and Ashanti slavery in particular, treated slavery as a condition based on circumstance. Slaves had rights, owners were not allowed to murder their slaves unless permitted by the King, slaves could own property, and the child of a slave and the master were free persons. Akans tried to ultimately incorporate a slave from another tribe into their own by making the child of a slave a free person. Coromantin realization that they and their descendants would be perpetually enslaved, unlike their system in Africa, may have been one of the reasons for the frequent rebellions—in addition to seeing themselves on equal footing with whites and having formerly been soldiers who may have themselves owned slaves.

Coromantee Led Rebellions

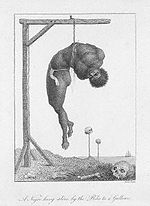

An engraving by William Blake illustrating "A negro hung by his ribs from a gallows," from Captain John Stedman's Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, 1792.

An engraving by William Blake illustrating "A negro hung by his ribs from a gallows," from Captain John Stedman's Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, 1792.

1690 Rebellion

There are several rebellions in the 1700s attributed to Coromantees. According to Edward Long, the first rebellion occurred in 1690 between three or four-hundred slaves in Clarendon Parish who after killing a white owner, seized firearms and provisions and killed an overseer at the neighboring plantation. [6] A militia was formed and eventually suppressed the rebellion hanging the leader. Several of the rebels fled and joined the Maroons. Long also describes the incident where a slave-owner “distinguished for his humanity towards his slaves, and in particular to one of his domestics, on whom he had bestowed many extraordinary marks of kindness” was overpowered by a group of Coromantees who after killing him, cut off his head, and sawed his skull turning it into a drinking bowl.[7] In 1739, the leader of Coromantee Maroons named, Cudjoe (Kojo) signed a treaty with the British ensuring the Maroons would be left alone provided they didn’t help other slave rebellions.[8]

1736 Antigua slave rebellion

In 1736 Antigua, a slave called "Prince Klaas" (whose real name was Court) planned an uprising in which whites would be massacred. Court was crowned "King of the Coromantees" in a pasture outside the capital of St. John's, in what white observers thought was a colourful spectacle, but was for the slaves a ritual declaration of war on the whites. Due to information obtained from other slaves, colonists discovered the plot and suppressed it. Prince Klaas and four accomplices were caught and executed by the breaking wheel. Six slaves were hanged in chains and starved to death, and another fifty-eight were burned at the stake. The site of these executions is now the Antiguan Recreation Ground.[9]

Tacky’s War

Main article: Tacky's WarIn 1760, another conspiracy known as Tacky's War was hatched. Organized by Tacky, a Coromanti, presumed to be of Fanti descent. Long claims that almost all Coromantin slaves on the island were involved without any suspicion from the Whites. Their plan was to overthrow British rule and establish an African kingdom in Jamaica. Tacky and his forces were able to take over several plantations and killed white plantation owners. However, they were ultimately betrayed by a slave named Yankee, whom Long describes as wanting to defend his masters house and “assist the white men” ran to the neighboring estate and with the help of another slave alerted the rest of the plantation owners.[10]

The British enlisted the help of Jamaican Maroons, who were themselves descendants of runaways and rebels to defeat the Coromantins. Edward Long describes a British man and a Mulatto man as each having killed three Coromantins. A British lieutenant tried to recruit Jewish slave owners to fight in the militia who refused. Long states that the Jews made “religious scruples of conscience their pretext, though it was well known that they never scrupled taking money or vending drams…others paid the fine and attended their shops.” In one anecdote, a Coromanti prisoner tried to bargain with a Jewish guard offering to split the island of Jamaica with Jews since, “You differ from whites and they hate you.” The guard refused the offer.

Eventually, Tacky was killed by a sharpshooter.[11]

Berbice Slave Uprising

Main article: Berbice Slave UprisingIn 1763, this slave rebellion occurred in Berbice in present day Guyana and was led by a Coromantin named Cuffy or Kofi and his deputy Akra or Akara. The slave rebellion from February 1763 into 1764.[12] Cuffy, like Tacky was born in West Africa before being enslaved. He led a revolt of more than 2,500 slaves against the colony regime. After acquiring firearms, the rebels attacked plantations.[13] They gained an advantage after taking house of Peerboom. They had told the whites inside that they could leave the house, but as soon as they left, the rebels killed many and took several prisoners, including the wife of a plantation owner whom Cuffy kept as his wife.

After several months, dispute between Cuffy and Akra led to a war between the two. On 2 April 1763 Cuffy wrote to Van Hoogenheim saying that he did not want a war against the whites and proposed a partition of Berbice with the whites occupying the coastal areas and the blacks the interior. Akara’s faction won and Cuffy killed himself. The anniversary of Cuffy’s slave rebellion, February 23 is Republic Day in Guyana, and Cuffy is a national hero in Guyana and he is commemorated in a large monument in the capital Georgetown.[14]

1765 Conspiracy

Coromantee slaves were also behind a conspiracy in 1765 to revolt. The leaders of the rebellion sealed their pact with an oath. Coromantee leaders Blackwell and Quamin (Kwame) ambushed and killed soldiers at a fort near Port Maria as well as other whites in the area.[15] They intended on allying with the Maroons to split up the island. The Coromantins were to give the Maroons the forests of Jamaica, while the Coromantins would control the cultivated land. The Maroons did not agree because of their treaty and existing agreement with British.[16]

1766 Rebellion

Thirty-three newly arrived Coromantins killed at least 19 whites in Westmoreland Parish. It was discovered when a young slave girl gave up the plans. All of the conspirators were either executed or sold.[17]

1822 Denmark Vesey conspiracy

Main article: Denmark VeseyIn 1822, an alleged conspiracy by slaves in the United States brought from the Caribbean was organized by a slave named Denmark Vesey or Telemaque. Historian Douglas Egerton suggested that Vesey could be of Coromantee (an Akan-speaking people) origin, based on a remembrance by a free black carpenter who knew Vesey toward the end of his life.[18] Inspired by the revolutionary spirit and actions of slaves during the 1791 Haitian Revolution, and furious at the closing of the African Church, Vesey began to plan a slave rebellion.

His insurrection, which was to take place on Bastille Day, July 14, 1822, became known to thousands of blacks throughout Charleston and along the Carolina coast. The plot called for Vesey and his group of slaves and free blacks to execute their enslavers and temporarily liberate the city of Charleston. Vesey and his followers planned to sail to Haiti to escape retaliation. Two slaves opposed to Vesey's scheme leaked the plot. Charleston authorities charged 131 men with conspiracy. In total, 67 men were convicted and 35 hanged, including Denmark Vesey.[19][20]

1823 Demerara Rebellion

Main article: Demerara rebellion of 1823Quamina (Kwamina) Gladstone, a Coromantee slave in Guyana, and his son Jack Gladstone led the Demerara rebellion of 1823, one of the largest slave revolts in the British colonies before slavery was abolished. He was a carpenter by trade, and worked on an estate owned by Sir John Gladstone. He was implicated in the revolt by the colonial authorities, apprehended and executed on 16 September 1823. He is considered a national hero in Guyana, and there are streets in Georgetown and the village of Beterverwagting on the East Coast Demerara, named after him.[21]

On Monday, 18 August 1823, Jack Gladstone – who had adopted surnames of their masters by convention – and his father, Quamina, both slaves on 'Success' plantation, led their peers to revolt against the harsh conditions and maltreatment.[22] Those on 'Le Resouvenir', where Smith's chapel was situated, also rebelled. Quamina Gladstone was a member of Smith's church,[23] The population broke down as follows: 2,500 whites, 2,500 freed blacks, and 77,000 slaves.[24] and had been one of five chosen to become deacons by the congregation soon after Smith's arrival.[25] Following the arrival of news from Britain that measures aimed at improving the treatment of slaves in the colonies had been passed, Jack had heard a rumour that their masters had received instructions to set them free but were refusing to do so.[26] In the weeks prior to the revolt, he sought confirmation of the veracity of the rumours from other slaves, particularly those who worked for those in a position to know: he thus obtained information from Susanna, housekeeper/mistress of John Hamilton of 'Le Resouvenir'; from Daniel, the Governor's servant; Joe Simpson from 'Le Reduit' and others. Specifically, Joe Simpson had written a letter which said that their freedom was imminent but which heeded them to be patient.[27] Jack wrote a letter (signing his father's name) to the members of the chapel informing them of the "new law".[26]

Being very close to Jack, he supported his son's aspirations to be free, by supporting the fight for the rights of slaves. But being a rational man,[28] and heeding the advice of Rev. Smith, he urged him to tell the other slaves, particularly the Christians, not to rebel. He sent Manuel and Seaton on this mission. When he knew the rebellion was imminent, he urged restraint, and made the fellow slaves promise a peaceful strike.[29] Jack led tens of thousands of slaves to raise up against their masters.[26] After the slaves' defeat in a major battle at 'Bachelor's Adventure', Jack fled into the woods. A "handsome reward"[30] of one thousand guilder was offered for the capture of Jack, Quamina and about twenty other "fugitives".[31] Jack and his wife were captured by Capt. McTurk at 'Chateau Margo' on 6 September after a three-hour standoff.[32] Quamina remained at large until he was captured on 16 September in the fields of 'Chateau Margo'. He was executed, and his body was hung up in chains by the side of a public road in front of 'Success'.[33]

Fictional Accounts

Main article: OroonokoOroonoko is a short work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn (1640–1689),[34] published in 1688, concerning the love of its hero, an enslaved African in Surinam in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences in the new South American colony. Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave is a relatively short novel concerning the grandson of a Coromantin African king, Prince Oroonoko, who falls in love with Imoinda, the daughter of that king's top general.[35]

The king, too, falls in love with Imoinda. He gives Imoinda the sacred veil, thus commanding her to become one of his wives, even though she has already married Oroonoko. After unwillingly spending time in the king's harem (the Otan), Imoinda and Oroonoko plan a tryst with the help of the sympathetic Onahal and Aboan. They are eventually discovered, and because she has lost her virginity, Imoinda is sold as a slave.[36] The king’s guilt, however, leads him to falsely inform Oroonoko that she has been executed, since death was thought to be better than slavery. Later, after winning another tribal war, Oroonoko is betrayed and captured by an English captain, who plans to sell him and his men as slaves. Both Imoinda and Oroonoko are carried to Surinam, at that time an English colony based on sugarcane plantation in the West Indies. The two lovers are reunited there, under the new Christian names of Caesar and Clemene, even though Imoinda's beauty has attracted the unwanted desires of other slaves and of the Cornish gentleman, Trefry.[37]

Upon Imoinda’s pregnancy, Oroonoko petitions for their return to the homeland. But after being continuously ignored, he organizes a slave revolt. The slaves are hunted down by the military forces and compelled to surrender on deputy governor Byam's promise of amnesty. Yet, when the slaves surrender, Oroonoko and the others are punished and whipped. To avenge his honor, and to express his natural worth, Oroonoko decides to kill Byam. But to protect Imoinda from violation and subjugation after his death, he decides to kill her. The two lovers discuss the plan, and with a smile on her face, Imoinda willingly dies by his hand. A few days later, Oroonoko is found mourning by her decapitated body and is kept from killing himself, only to be publicly executed. During his death by dismemberment, Oroonoko calmly smokes a pipe and stoically withstands all the pain without crying out.[38]

Bill to Ban Importation

In 1765 a bill was proposed to prevent the importation of Coromantees but did not pass. Edward Long, an anti-Coromantee writer states

Such a bill, if passed into law would have struck at very root of evil. No more Coromantins would have been brought to infest this country, but instead of their savage race, the island would have been supplied with Blacks of a more docile tractable disposition and better inclined to peace and agriculture.[39]

Colonist later devised ways of separating Coromantins from each other, by housing them separately, placing them with other slaves, and stricter monitoring of activities. Since groups like the Igbo people were hardly reported to have been maroons, Igbo women were paired with Coromantee men so as to subdue the latter due to the idea that Igbo women were bound to their first born sons' birth place.[40]

Assimilation

Other Coromantee revolts followed but these were all quickly suppressed. Coromantees and their Akan brethren amongst the Maroons influenced black Jamaican culture for some time. After British abolition of slavery in 1833, their influence and reputation began to wane as Coromantins were fully integrated into the larger Jamaican community.

References

- ^ Thornton, John (2000), pp. 181

- ^ Thornton, John (2000), pp. 186

- ^ Thornton, John (2000), pp. 182

- ^ Egglestone, Ruth (2001). "A Philosophy of Survival: Anancyism in Jamaican Pantomime" (pdf). The Society for Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers 2: 1471–2024. http://www.caribbeanstudies.org.uk/papers/2001/olv2p5.pdf.

- ^ Egglestone(2001), pdf

- ^ Long, Edward (1774) (google). The History of Jamaica Or, A General Survey of the Antient and Modern State of that Island: With Reflexions on Its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government. 2. pp. 445–475. http://books.google.com/books?id=QLw_AAAAcAAJ&dq=edward%20long%20coromantee&pg=PA446#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 447

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 345

- ^ Brian Dyde, "A History of Antigua", Macmillan Education, London and Oxford, 2000.

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 451

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 468

- ^ Smith, Simon David (2006). Slavery, family, and gentry capitalism in the British Atlantic: the world of the Lascelles, 1648-1834. Cambridge University Press. pp. 116. ISBN 0521863384.

- ^ Ishmael, Odeen (2005). The Guyana Story: From Earliest Times to Independence (1st ed.). http://www.guyana.org/features/guyanastory/guyana_story.html. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ David Granger (1992). "Guyana coins". El Dorado, 2nd Issue, p.20-22. http://www.guyanaguide.com/guyanacoins.html. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 465

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 460-470

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pp. 471

- ^ Egerton (2004), p. 3-4

- ^ "Denmark Vesey", Knob Knowledge, Daniel Library, The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina.

- ^ "About The Citadel", Office of Public Affairs, The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, May 2001.

- ^ "Historic Cummingsburg". National Trust of Guyana. http://www.nationaltrust.gov.gy/historiccummings.html. Retrieved 25 November 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Sheridan, Richard B. (2002). "The Condition of slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara 1812 to 1849" (pdf). New West Indian Guide 76 (3/4): 243–269. http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/article/view/3455/4216.

- ^ Révauger, Cécile (October 2008). The Abolition of Slavery - The British Debate 1787–1840. Presse Universitaire de France. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-2-13-057110-0.

- ^ da Costa (1994), pg. xviii

- ^ da Costa (1994), pg. 145

- ^ a b c "PART II Blood, sweat, tears and the struggle for basic human rights". Guyana Caribbean Network. http://www.guyanacaribbeannetwork.com/ourfeature.08.04.08.htm. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ da Costa (1994), pp. 180, 196

- ^ da Costa (1994), pg. 182

- ^ "The Demerara Slave Uprising". Guyana News and Information. http://www.guyana.org/features/guyanastory/chapter43.html. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Bryant (1824), pg. 83.

- ^ da Costa (1994), pg. 180.

- ^ Bryant (1824), pp. 83-4.

- ^ Bryant (1824), pg. 87-8.

- ^ "Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave. A True History.". http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/behn/aphra/b42o/. Retrieved 2006-02-07.

- ^ Hutner 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern,

- ^ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern, 13

- ^ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern.

- ^ Long, Edward (1774), pg. 471

- ^ Mullin, Michael (1995). Africa in America: slave acculturation and resistance in the American South and the British Caribbean, 1736-1831. University of Illinois Press. p. 26. ISBN 02-520-6446-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=so71jZ6mHBAC&pg=PA26.

Notes

- Behn, A., Gallagher, C., & Stern, S. (2000). Oroonoko, or, The royal slave. Bedford cultural editions. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Williams, Brackette (1990), "Dutchman Ghosts and the History Mystery: Ritual, Colonizer, and Colonized Interpretations of the 1763 Berbice Slave Rebellion", Journal of Historical Sociology 3 (2): 133–165, doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.1990.tb00094.x.

- Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

- Bryant, Joshua (1824). Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823.. Georgetown, Demerara: A. Stevenson at the Guiana Chronicle Office. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=rLUNAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Account+of+an+insurrection+of+the+negro+slaves+in+the+colony+of+Demerara,+which+broke+out+on+the+18th+of+August,+1823#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Hutner, Heidi (1993). Rereading Aphra Behn: history, theory, and criticism. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813914434

- Thornton, John K. (2000). War, the State, and Religious Norms in "Coromantee" Thought: The Ideology of an African American Nation-- Possible pasts: becoming colonial in early America. ISBN 0801483921. http://books.google.com/books?id=wmjSSH4hHNcC&lpg=PA181&dq=war%2C%20the%20state%2C%20and%20religious%20norms%20in%20coromantee&pg=PA181#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Viotti da Costa, Emília (18 May 1994). Crowns of glory, tears of blood: the Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. ISBN 0195106563. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=WzBeW7arNbMC&pg=PP1&dq=crowns+of+glory+tears+of+blood#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

From the Americas Taíno/Arawak

From Africa From Asia From Europe Categories:- Akan

- Slave rebellions

- History of Jamaica

- Conflicts in 1760

- 18th-century rebellions

- Ethnic groups in Jamaica

- Jamaican Maroons

- Jamaica

- Jamaican people

- History of Guyana

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.