- Assassination of William McKinley

-

Assassination of William McKinley

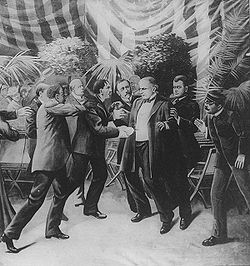

Leon Czolgosz shoots President McKinley with a concealed revolver.Location Buffalo, New York Date September 6, 1901

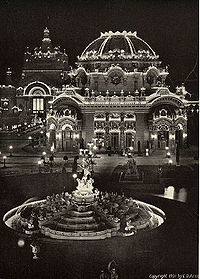

4:07 p.m. (Eastern Time)Target William McKinley Weapon(s) Revolver Death(s) 1 (McKinley) Injured None Perpetrator(s) Leon Czolgosz The assassination of William McKinley occurred on September 6, 1901, inside the Temple of Music located on the grounds of the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. United States President William McKinley was visiting the Exposition and was standing in a receiving line shaking hands with ordinary citizens when he was shot twice by Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist.

McKinley initially appeared to be recovering from his wounds, but took a turn for the worse on September 12, six days after the shooting. Over the course of the next two days his health quickly deteriorated and he died on September 14, 1901. Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt succeeded McKinley as President. McKinley was the third out of four U.S. presidents who have been assassinated, following Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and James A. Garfield in 1881, and preceding John F. Kennedy in 1963. It was after McKinley's murder that the U.S. Congress passed legislation to officially charge the Secret Service with the responsibility for providing the physical protection of all U.S. presidents.

Contents

McKinley at the Exposition

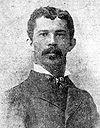

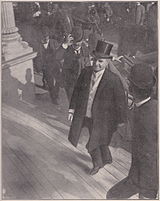

McKinley arrives at the Temple of Music, shortly before his assassination.

McKinley arrives at the Temple of Music, shortly before his assassination.

McKinley and his wife, Ida, arrived at the Exposition the previous day on September 5, which had been designated as "President's Day" in his honor.[1] Events scheduled for that day included private receptions and a military review[2] as well as a speech to be given by McKinley.[3]

On the morning of the 6th, McKinley visited Niagara Falls and returned to the Exposition for a scheduled public reception that afternoon. His secretary, George B. Cortelyou, disliked such public receptions, believing them to be security risks.[4] Cortelyou suggested that McKinley should skip the reception, but McKinley replied, "Why should I? No one would wish to hurt me."[5] McKinley, accompanied by Cortelyou and Exposition president John Milburn, arrived at the Exposition at 3:30 p.m. and proceeded to the Temple of Music building where the reception was to take place.[5]

Even after the assassination of President Garfield in 1881, no organization was given any official mandate to provide Presidential security. However, the U.S. Secret Service, founded in 1865 to combat counterfeiting, had already provided informal, occasional security since 1894, starting with McKinley's predecessor Grover Cleveland.[6] The Secret Service was there that day to protect the President, along with Buffalo detectives and a squad of eleven Army servicemen that had been instructed to keep an eye on the crowd.[7] McKinley, flanked by Cortelyou and Milburn, stood and shook hands with the people filing by in a long line. Waiting in that line was Leon Czolgosz.

The assassin

Czolgosz was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1873, the son of Polish immigrants.[8][9](p85) He was an unemployed factory worker and was living with his family in 1901. Czolgosz became interested in anarchism in the years preceding the McKinley murder. In May 1901 he attended a speech given by renowned anarchist Emma Goldman, in Cleveland, Ohio. Czolgosz traveled to Goldman's home in Chicago on July 12 and spoke briefly to Goldman before she left to catch a train.[10] Goldman was later arrested and briefly detained on suspicion of involvement in McKinley's murder.[11][12]

In his September 7 statement, Czolgosz said that he had read eight days prior, in Chicago, that McKinley would be attending the Exposition. He immediately took a train to Buffalo and found lodgings in a boarding house. Czolgosz attended the fair on September 5 for President's Day and heard McKinley's speech. He was tempted to shoot the President then but he could not get close enough. Instead, he returned to the Exposition the next day. Goldman's speech from May was still "burning [him] up". He joined the line of people waiting to shake the president's hand. Czolgosz wrapped his hand in a white handkerchief to hide the gun he was carrying.[13] Secret Serviceman George Foster later explained his failure to observe Czolgosz's wrapped-up hand by saying that Czolgosz was too closely bunched up to the man in front of him.[14] However, at the trial, Foster also admitted to not noticing Czolgosz because he was paying close attention to James Parker,[15] a six-foot six inch black waiter from Atlanta laid-off by the exposition's Plaza Restaurant, who was standing immediately behind Czolgosz.

The shooting

McKinley had been shaking hands for approximately ten minutes when Cortelyou left his side to shut the doors. William J. Gomph, the exposition's official organist, was softly playing Schumann's Träumerei on the massive organ that was a special attraction at the Temple of Music. At this moment, 4:07 p.m.[16] Czolgosz advanced to face the President.[17] McKinley reached out to take Czolgosz's "bandaged" hand, but before he could shake it Czolgosz pulled the trigger twice. James Parker punched Czolgosz in the face and tackled him,[18][19] knocking the gun from Czolgosz's hand.[20] Agent George Foster jumped onto Czolgosz and shouted to fellow agent Albert Gallagher "Al, get the gun! Get the gun! Al, get the gun!"[21] Gallagher instead got Czolgosz's handkerchief, which was on fire. Private Francis O'Brien, of McKinley's Army detail, picked up the gun.[22]

McKinley remained standing while security dragged Czolgosz away. After someone hit Czolgosz again, McKinley spoke softly "Go easy on him boys."[23] Eleven minutes after the shooting an ambulance arrived and McKinley was taken to the hospital on the Exposition grounds.[16] He had been shot twice. One bullet deflected off his ribs, making only a superficial wound. However, the second bullet hit McKinley in the abdomen, passed completely through his stomach, hit his kidney, damaged his pancreas, and lodged somewhere in the muscles of his back.

The doctors, unable to find the bullet, left it in his body and closed up the wound.[24] An experimental X-ray machine, which might have helped to find the bullet, was on hand at the exhibition, but for unknown reasons, it was not used. (In the following days Thomas Edison arranged for an X-ray machine to be delivered all the way from his shop in New Jersey, but it was never used either).[25][26] McKinley, still unconscious from the ether used to sedate him, was taken to John Milburn's home to recover.[27]

Death of the President

Czolgosz confessed everything that night stating, "I killed President McKinley because I done my duty. I didn't believe one man should have so much service and another man should have none."[28] He provided more detail the next day,[13] insisting that he acted alone, although his statement did not prevent Goldman's arrest a few days later.

Contrary to Czolgosz's assertion that he had killed the President, McKinley not only was still alive, but seemed to be recovering. On Saturday, September 7, McKinley was in good condition, relaxed and conversational. His wife was allowed to see him, and he asked Cortelyou, "How did they like my speech?"[29] A bulletin sent from his sickbed on September 8 said, "The President passed a good night and his condition this morning is quite encouraging. His mind is clear and he is resting well. Wound dressed at 8:30 and found in a very satisfactory condition."[30]

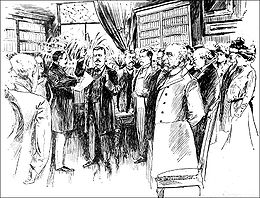

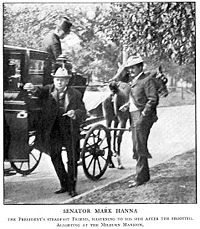

Senator Mark Hanna, friend of President McKinley, arriving at Milburn Mansion after the shooting.

Senator Mark Hanna, friend of President McKinley, arriving at Milburn Mansion after the shooting.

Most of McKinley's cabinet came to Buffalo, as well as his old friend and former campaign manager, Senator Mark Hanna.[31] Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was attending a luncheon event in Vermont on September 6 when word came that the President had been shot.[32] Roosevelt and his party left immediately for Buffalo, arriving the next day. However, by September 10, McKinley had improved to the point that Roosevelt's presence no longer seemed necessary, and, for the sake of publicity, the Vice President left Buffalo that day. He went to take a hiking vacation in the Adirondack Mountains, where his wife and family were already waiting.[33] Similarly, Mark Hanna and the cabinet members left Buffalo when the crisis seemed to have passed.[34]

The President continued to improve. A bulletin on September 9 stated, "The President's condition is becoming more and more satisfactory. Untoward incidents are less likely to occur." On September 10 a bulletin stated, "The President's condition this morning is eminently satisfactory to his physicians. If no complications arise a rapid convalescence may be expected." McKinley continued to take water orally and nutritive enemas. On September 11, the President took beef juice orally, the first food he'd taken in the stomach since the shooting. Bulletins said "continues to gain" and "condition continues favorably." On September 12, McKinley had his first solid food, some toast and egg with coffee, but he "did not relish it and ate very little."[24][30] Later that day, the President's condition began to worsen. He reported headache and nausea and his pulse rate increased, rapid but weak. McKinley became sweaty and restless, although he remained conscious and alert. A bulletin on the morning of September 13 said, "The President's condition is very serious, and gives rise to the gravest apprehension." That day, Friday, September 13, McKinley began rapidly deteriorating. Hanna and the cabinet returned to the Milburn house.[35] McKinley was given adrenaline and oxygen in attempts to improve his weak pulse.[24][30] His condition worsening, McKinley told his doctors, “It is useless, gentlemen, I think we ought to have prayer.”[36] Later, as he faded, McKinley whispered the words to the hymn that in 11 years would be played on the sinking ship RMS Titanic, "Nearer, My God, to Thee."[37] A bulletin at 6:15 p.m. said, "The President's physicians report that his condition is most serious in spite of vigorous stimulation... unless it can be relieved the end is only a question of time."[30]

Senator Hanna, grief stricken, said "Mr. President, can't you hear me? William! Don't you know me?"[38] President McKinley, brought down by infection and gangrene, died at 2:15 a.m. on September 14, 1901.

Roosevelt succeeds to the Presidency

On September 12, Theodore Roosevelt met his family at their cabin near Mount Marcy, located in the high-peaks region of the Adirondacks, approximately 375 miles from Buffalo. The next morning, a cold, foggy day, Roosevelt left for a climb to the top of the mountain, accompanied by friends and a park ranger. By noon on September 13, the Vice President and his party stopped to rest at the 5,344 feet (1,629 m)-high summit on a large flat rock that offered a panoramic view of the mountains.[39] They climbed back down five hundred feet to have lunch by a lake. At about 1:30, a park ranger arrived bearing a telegram.[40] Roosevelt understood as soon as he saw the messenger what had happened, saying later: "I instinctively knew he had bad news... I wanted to become President, but I did not want to become President that way."[41]

The telegram confirmed his fears, reporting that McKinley's condition had turned very much for the worse. After returning to his cabin, Roosevelt received a dire telegram from Secretary of War Elihu Root:

THE PRESIDENT APPEARS TO BE DYING AND MEMBERS OF THE CABINET IN BUFFALO THINK YOU SHOULD LOSE NO TIME COMING

Just before midnight, Roosevelt left his family for a carriage ride down the mountain, a trip that even in daylight usually took seven hours.[42] At 3:30 a.m. Roosevelt boarded another wagon and continued the long, twisting ride at high speed in the dark.[43] Two hours later, Roosevelt finally arrived at the train station in North Creek, New York, where, at 5:22 a.m. on September 14, he received a telegram from Secretary of State John Hay:

THE PRESIDENT DIED AT TWO-FIFTEEN THIS MORNING

Roosevelt then boarded the train.[44] The train stopped briefly in Albany before pulling into Buffalo at 1:30 p.m.[45] There he met his friend Ansley Wilcox and went to Wilcox's house, one mile (1.6 km) from Milburn's house where McKinley's body lay. After cleaning up, Roosevelt went to the Milburn house to pay his respects. He met with Mrs. McKinley, Root, Cortelyou, and most of the rest of the cabinet there, but could not see McKinley's body as the autopsy was underway. Root recommended holding the ceremony there, but Roosevelt thought that "inappropriate" and decided to return to the Wilcox house for the swearing-in ceremony. Roosevelt took the oath of office as the 26th President of the United States at 3:30 p.m.[46] Six weeks away from his 43rd birthday, he remains the youngest man ever to hold the office of President.

One of Roosevelt's first acts as President was to issue a pronouncement declaring: "When compared with the suppression of anarchy, every other question sinks into insignificance.”[47]

Aftermath

Czolgosz went on trial on September 23, 1901, only nine days after the President died. Prosecution testimony took two days and consisted of the doctors who treated McKinley and various eyewitnesses to the shooting. Defense counsel Loran Lewis did not call any witnesses. In his statement to the jury, Lewis noted Czolgosz's refusal to talk to his lawyers or cooperate with them, admitted his client's act, and said that "the only question that can be discussed or considered in this case is... whether that act was that of a sane person. If it was, then the defendant is guilty of the murder... If it was the act of an insane man, then he is not guilty of murder but should be acquitted of that charge and would then be confined in a lunatic asylum."

The jury took only half an hour to convict Czolgosz. On September 26, Czolgosz was sentenced to death.[22] He was immediately taken to Auburn State Prison to await execution.[48] According to one account, Czolgosz expressed remorse on his way to Auburn, saying, "I wish the people to know I am sorry for what I did. It was a mistake and it was wrong. If I had it to do over again I never would do it. But it is too late now to talk of that. I am sorry I killed the President."[49] Czolgosz was executed by means of electrocution on October 29, 1901.[48] His last words are variously reported as, "I killed the President for the good of the laboring people, the good people. I am not sorry for my crime but I am sorry I can't see my father"; or, "I killed the President because he was the enemy of the good people—the good working people. I am not sorry for my crime."[9](pp311 & 430)

Emma Goldman incurred a great deal of negative publicity when she published an article in which she compared Czolgosz to Marcus Junius Brutus, the killer of Julius Caesar, and called McKinley the "president of the money kings and trust magnates."[50] Some other anarchists and radicals were unwilling to help Goldman's effort to aid Czolgosz, believing that he had harmed the movement.[51] Goldman subsequently withdrew from public life for a time.

After McKinley's murder, newspaper editorials across the country heavily criticized the lack of protection afforded to United States Presidents. Congress quickly took up the question of Presidential security. In the fall of 1901 they informally asked the Secret Service to control presidential security, and the Service was protecting President Theodore Roosevelt full-time by 1902. However, this was not yet official. Some in Congress recommended the United States Army be charged with protecting the President.[52] Not until 1906 did the Congress pass legislation officially designating the Secret Service as the agency in charge of presidential security.[53][54] As an added security measure, Roosevelt considered it prudent to carry a concealed revolver.[55]

The Temple of Music was demolished in late 1901 and the grounds of the Pan American Exposition were cleared for residential development. A boulder with a metal plaque near 30 Fordham Drive marks the location where McKinley was shot.[56] The Milburn house at 1168 Delaware Avenue, where McKinley died, was turned into an apartment building in 1919 and later demolished in 1956 in order to create an additional parking lot for Canisius High School. Students of the school watched the demolition from their classroom windows.[57] The Ansley Wilcox Mansion in Buffalo, where Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office, is now a National Historic Site.[58] In 1907, Buffalo dedicated a 96-foot (29 m)-tall marble obelisk in Niagara Square to McKinley's memory.[59][60]

References

Program cover for memorial service in Nashua, New Hampshire on September 19, 1901

Program cover for memorial service in Nashua, New Hampshire on September 19, 1901

- ^ "Images of President McKinley at the Pan-American Exhibition

- ^ "Official Daily Program of the Pan-American Exposition, Sept. 5, 1901"

- ^ "William McKinley's Pan-American Address"

- ^ Olcott, Charles. The Life of William McKinley. Houghton Mifflin company, Boston, 1916, p. 313

- ^ a b Olcott, 314

- ^ Bumgarner, Jeffrey. Federal Agents: The Growth of Federal Law Enforcement in America. Greenwood Press, 2006, ISBN 0275989534, p. 44

- ^ Olcott 314–5

- ^ Johns, p. 36.

- ^ a b Seibert, Jeffrey (2002). I Done My Duty: The Complete Story of the Assassination of President McKinley. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-2118-1.

- ^ Goldman, Emma. Living My Life. New York: Courier Dover, 1970 edition. ISBN 0486225437, pp. 289–91

- ^ New York Times, Sept. 11, 1901

- ^ Goldman 296–304

- ^ a b New York Times, Sept. 8, 1901

- ^ Townsend, G.W. Memorial Life of William McKinley. 1901, p. 465

- ^ Rauchway 61

- ^ a b Olcott 317

- ^ Olcott 315

- ^ "James B. Parker Revisited"

- ^ "Big Ben Parker and President McKinley's Assassination"

- ^ Rauchway 62–3

- ^ Townsend 464

- ^ a b "The Trial"

- ^ Olcott 316

- ^ a b c The Official Report on the Case of President McKinley

- ^ Kevles, Bettyann. Naked to the Bone: Medical Imaging in the Twentieth Century. Basic Books, 1998. ISBN 020132833X. p. 42–3

- ^ X-rays at the Exhibition

- ^ Olcott 319

- ^ "The Confession of Leon Czolgosz"

- ^ Olcott 320

- ^ a b c d "Medical and Surgical Report" by Dr. Presley M. Rixey

- ^ Olcott 321

- ^ Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, Modern Library 2001 paperback edition, ISBN 0375756787, p. 777

- ^ Morris, Rise, 778

- ^ Olcott 322

- ^ Olcott 323

- ^ Olcott 324

- ^ Olcott 325

- ^ Beschloss, Michael. Presidential Courage: Brave Leaders and How They Changed America 1789-1989. Simon and Schuster, 2007, p. 128. ISBN 0684857057.

- ^ Morris, Rise, 779

- ^ Morris, Rise, 780

- ^ Morris, Rise, 889, endnote 16

- ^ Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex, Random House, 2001. ISBN 0394555090, p. 3

- ^ Morris, Rex, 4–6

- ^ Morris, Rex, 7

- ^ Morris, Rex, 9–11

- ^ Morris, Rex, 11–15

- ^ Doherty, Brian (2010-12-17) The First War on Terror, Reason

- ^ a b "The Execution of Leon Czolgosz"

- ^ "Regrets His Crime". The Buffalo Express, September 27, 1901.

- ^ "The Tragedy at Buffalo"

- ^ Goldman 311–319

- ^ Bumgarner 45

- ^ Bumgarner 46

- ^ History of the Secret Service

- ^ "ROOSEVELT USUALLY CARRIED A REVOLVER; Considered McKinley's Assassination Bore a Peculiar Application to Himself". New York Times: p. 3. 14 October 1912. http://nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00C15FC385813738DDDAC0994D8415B828DF1D3.

- ^ Buffalo Historical Markers and Monuments

- ^ John Milburn

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site

- ^ Buffalo Arts Commission - City of Buffalo

- ^ McKinley Monument

Further reading

- Fisher, Jack C. Stolen glory : the McKinley assassination. La Jolla, CA : Alamar Books, ©2001

- Johns, A. Wesley. The man who shot McKinley. South Brunswick [N.J.]: A.S. Barnes [1970]

- Lowy, Jonathan. The Temple of Music: A Novel. Three Rivers Press, 2005. ISBN 0307209849. A novel of the assassination.

- Rauchway, Eric. Murdering Mckinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt's America. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2004. ISBN 0809016389, 9780809016389

External links

- Assassination of President McKinley: A Bibliography showing books and manuscripts owned by the library at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.

- McKinley Assassination Ink. Comprehensive collection of primary source materials on the McKinley assassination

- "Lights out in the City of Light"; Anarchy and Assassination at the Pan-American Exposition

- McKinley assassination at the Crime Library

- Film archive of the Pan American Exposition, at the Library of Congress. Include clips of McKinley's funeral train, McKinley at the Exposition reviewing the troops on Sept. 5, and the crowd outside the Temple of Music after the shooting.

- Q&A interview with Scott Miller on The President and the Assassin, June 22, 2011

United States presidential assassination attempts List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots Successful assassinations Failed attempts Andrew Jackson · Abraham Lincoln · Theodore Roosevelt · Franklin D. Roosevelt · Harry S. Truman · John F. Kennedy · Richard M. Nixon · Gerald R. Ford · Jimmy Carter · Ronald Reagan · George H. W. Bush · Bill Clinton · George W. BushPresidential deaths rumored

to be assassinationsCoordinates: 42°56′19″N 78°52′25″W / 42.93861°N 78.87361°W

Categories:- 1901 crimes

- Assassinations

- History of Buffalo, New York

- 1901 in the United States

- 1901 in New York

- William McKinley

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.