- Menominee Tribe v. United States

-

Menominee Tribe v. United States

Supreme Court of the United StatesArgued January 22, 1968

Reargued April 26, 1968

Decided May 27, 1968Full case name Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States Citations 391 U.S. 404 (more)

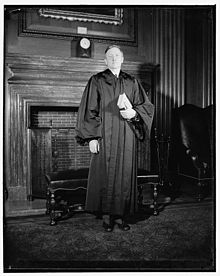

88 S.Ct. 1705, 20 L.Ed. 697Prior history Menominee Tribe of Indians et al. v. United States, 388 F.2d 998 (Ct. Cl. 1967). Holding Held that tribal hunting and fishing rights retained by treaty were not abrogated by the Menominee Termination Act without a clear and unequivocal statement to that effect by Congress Court membership Chief Justice

Earl WarrenAssociate Justices

Hugo Black · William O. Douglas

John M. Harlan II · William J. Brennan, Jr.

Potter Stewart · Byron White

Abe Fortas · Thurgood MarshallCase opinions Majority J. Douglas Dissent J. Stewart, joined by J. Black J. Marshall took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. Laws applied 10 Stat. 1064 (1854), 25 U.S.C. §§ 891–902, 18 U.S.C. § 1162 Menominee Tribe v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968), was a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the tribal hunting and fishing rights which were retained by treaty were not abrogated by the Menominee Termination Act without a clear and unequivocal statement to that effect by Congress.[1] The Menominee Indian Tribe had entered into a series of treaties with the United States which did not specifically state that they had hunting and fishing rights. In 1961 Congress terminated the tribe's federal recognition, ending the tribe's right to govern itself, federal support of health care and education programs, police and fire protection, and tribal rights to land. In 1963, three members of the tribe were charged with violating Wisconsin's hunting and fishing laws on what had formerly been reservation land for over 100 years. A series of court cases brought the issue to the Supreme Court. The court held that the tribe retained its hunting and fishing rights under the treaties involved. This case has since become recognized as a landmark case in Native American case law.

Contents

Background

Early treaties

The Menominee Indian Tribe lived in the states of Wisconsin and Michigan for at least 10,000 years.[2][3] They first acknowledged that they were under the protection of the United States in the Treaty of St. Louis in 1817.[4][5] In 1825 and 1827 the treaties of Prairie du Chien[5][6] and Butte des Morts (7 Stat. 303)[5][7] answered boundary questions. None of the early treaties addressed hunting and fishing rights.[4][6][7] In 1831 the tribe entered into another treaty, the Treaty of Washington (7 Stat. 342 (1831) and 7 Stat. 405 (1832)),[5][8] which ceded about 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km2) to the federal government. These two treaties reserved hunting and fishing rights for the tribe on the ceded land until the President surveyed and sold the land. In 1836 the tribe entered into the Treaty of Cedar Point (7 Stat. 506),[5][9] where 4,184,000 acres (16,930 km2) was ceded to the federal government. There was no mention of hunting or fishing rights in this treaty.

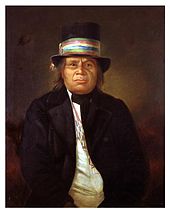

In 1848 the tribe entered into another treaty with the United States, the Treaty of Lake Poygan,[5][10] where the tribe ceded their remaining approximately 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) in exchange for 600,000 acres (2,400 km2) west of the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota. This treaty was contingent on the tribe examining the land proposed for them and accepting it as suitable. Chief Oshkosh led a delegation in 1850 to the Crow Wing area and determined that the land was not suitable for the tribe, primarily due to the location of the proposed reservation being between two warring tribes, the Dakota[Note 1] and Ojibwe.[Note 2] Oshkosh then pressed for a new treaty, stating that he "preferred a home somewhere in Wisconsin, for the poorest region in Wisconsin was better than the Crow Wing."[13]

Treaty of 1854

In the meantime, the tribe had been living in an area near the Wolf River. They then entered into the Treaty of Wolf River (10 Stat. 1064) with the United States in 1854.[5][14] The United States set aside 276,480 acres (1,118.9 km2; 432.00 sq mi) of land for a reservation in present day Menominee County, Wisconsin. In return, the tribe ceded the land in Minnesota back to the federal government. All of the previous treaties but one[Note 3] did not provide for hunting and fishing rights, but stated that the reservation was "to be held as Indian lands are held".[1][5][14]

From that date forward for 100 years, this area has been the home of the tribe, and they were free from state interference. Of the original land, 230,000 acres (930 km2; 360 sq mi) of prime timberland remained under the control of the tribe, while the remaining land was transferred to the Mahican and Lenape tribe.[Note 4] During this period, the tribe enjoyed complete freedom to regulate hunting and fishing on the reservation, with the complete acquiescence of Wisconsin.[5]

Tribal termination

In the mid to late-1940s, the tribe was part of a survey to identify tribes for termination, a process in which federal recognition of the tribe would be withdrawn and the tribe would no longer be dependent on the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to support them.[16] The Menominee were thought to be a tribe that would be able to be terminated due to being one of the richest tribes in the nation.[17] The thought of the federal government was that termination would allow the tribal members to be assimilated into mainstream American culture, becoming hard-working, tax-paying productive citizens.[18] In 1954, Congress terminated the federally recognized status of the Menominee in Menominee Indian Termination Act, codified at 25 U.S.C. §§ 891–902.[19] According to the terms of the Termination Act, the federally recognized status was to end in 1958. The tribe and the state of Wisconsin successfully lobbied to delay the termination to 1961.[20]

On termination, the Menominee went from being one of the wealthiest tribes to one of the poorest. In 1954, the tribe was paying its own way due to its timber operations.[Note 5] The tribe paid for a hospital, BIA salaries, local schools, and owned utility companies, plus a stipend to tribal members. The tribe was forced to use its reserve funds to develop a termination plan that they did not want, and instead of having a reserve, entered into termination with a US$300,000 deficit.[21] Menominee County was created out of the old reservation boundaries, and the tribe immediately had to provide for its own police and fire protection.[Note 6] Without federal support and with no tax base, the situation became dire. The tribe closed the hospital and sold its utility company, and contracted those services to neighboring counties.[21] The Menominee Enterprises, Inc., formed to care for the tribe's needs after termination, was unable to pay property taxes and began to consider selling off tribal property.[17] Many Menominee tribal members believed that the sponsor of the termination bill, Senator Arthur Wilkins of Utah, intended to force the loss of rich tribal lands to non-Indians.[17] In 1962, the state of Wisconsin took the position that the hunting and fishing rights were abrogated by the termination act and that the tribal members were subject to state hunting and fishing regulations. With the poverty in the former reservation, the loss of hunting rights meant the loss of one of their last remaining means of survival.[23]

State enforcement actions

In 1962, Joseph L. Sanapaw, William J. Grignon, and Francis Basina were charged with violating state hunting and fishing regulations.[1][24] All three were members of the tribe and admitted to the acts in open court, but claimed that the Wolf River Treaty gave them the right to hunt. The state trial court agreed, and acquitted the three. The state was given leave to pursue a writ of error, and appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court to answer the question if the Termination Act canceled those rights retained by treaty.[24]

The Wisconsin Supreme Court in State v. Sanapaw, 124 N.W.2d 41 (Wis., 1963),[24] held that the treaty rights were terminated by Congress. In analyzing the case, the court found first that although the Wolf River Treaty did not specifically mention hunting and fishing rights, the term "to be held as Indian lands are held"[14] was clear. Indians have always been able to hunt and fish on their own land, and if a term in a treaty with Indians is ambiguous, the court found that it must be resolved in favor of the tribe. Since the tribe had hunting and fishing rights under the treaty, the court then looked to determine if Congress had removed that right by enacting the Menominee Termination Act. The court held that Congress had used its plenary power to abrogate those rights.[24]

The key point to the court was the phrase "all statutes of the United States which affect Indians because of their status as Indians shall no longer be applicable to the members of the tribe, and the laws of the several States shall apply to the tribe and its members in the same manner as they apply to other citizens or persons within their jurisdiction." [Emphasis by the court.][24] The court held that the latter section was controlling, despite the argument by the tribal members that hunting rights were retained by treaty, not statute. The court held that the tribe had lost their hunting and fishing rights.[24] The tribal members appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the appeal.[25]

Federal Court of Claims

The Menominee[Note 7] sued to recover compensation for the loss of the hunting and fishing rights in the U.S. Court of Claims. The court first clarified that the Menominee Termination Act did not abolish the tribe or its membership, but merely ended Federal supervision of the tribe. Since the Menominee was still a tribe, although not one under federal trusteeship, the tribe had a right to assert a claim arising out the Wolf River Treaty in accordance with the Indian Claims Commission Act and the Tucker Act.[5][26][27]

The Court looked at whether the tribe had hunting and fishing rights, and drew the same conclusion as the Wisconsin Supreme Court—that the terms of the treaty had to be resolved in the favor of the tribe, citing The Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 95 Ct.Cl. 232 (Ct.Cl., 1941). In that decision, the court had observed that the reason the tribe had agreed to the current reservation was that it was well suited for hunting, with plenty of game.[28] The hunting rights by treaty were therefore confirmed.[5]

The court had to determine if the Menominee Termination Act had taken away that right. If it had, the tribe would have had a valid claim for compensation; but if not, then there would be no compensation. The court denied the claim, stating that the hunting and fishing rights had not been abrogated. In arriving at this decision, it commented that the legislative history included two witnesses who stated that the law would not affect hunting and fishing rights acquired by treaty, but would abrogate any such rights acquired by statute.[19] Additionally, the court observed that Congress also amended Public Law 280 so that Indian hunting and fishing rights were protected in Wisconsin.[5][29]

The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari (a writ to the lower court to send the case to them for review) to resolve the conflict between the state court and the federal court.[1]

Opinion of the Court

In an interesting twist, both the appellee (the Menominee) and the appellant (the United States) argued that the decision of the Court of Claims should be affirmed. The State of Wisconsin, as amicus curiae, argued that the lower court should be reversed.[1]

Majority opinion

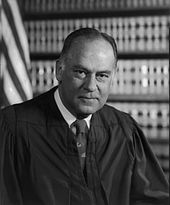

Justice William O. Douglas delivered the opinion of the court. The decision of the U.S. Court of Claims was affirmed. Douglas noted that Public Law 280 had been enacted and was fully in force for approximately seven years before the Termination Act became effective. The section of that law that dealt with Wisconsin provided that hunting and fishing rights in "Indian Country" were protected from state regulation and action. Thus from 1954 until termination in 1961, the Menominee's hunting and fishing rights were not interfered with by Wisconsin. The Termination Act stated that all federal statutes dealing with the tribe were no longer in force, but Douglas noted that it was silent as to treaties. The act did not specifically address the hunting and fishing rights, and Douglas stated that the court would "decline to construe the Termination Act as a backhanded way of abrogating the hunting and fishing rights of these Indians."[1] He noted that in a similar bill for the Klamath Tribe, there was a discussion on paying the tribe to buy out their hunting and fishing rights, a clear indication that Congress was aware of the implications. Douglas found it hard to believe that Congress would subject the United States to a claim for compensation without an explicit statement to that effect. He found that without a specific abrogation of those rights, the tribe retained those rights.[1]

Dissent

Justice Potter Stewart, joined by Justice Hugo Black, dissented. Stewart acknowledged that the Wolf River Treaty "unquestionably" conferred hunting and fishing rights on the tribe and its members. He stated that the Termination Act subjected the members of the tribe to the same laws that all other citizens of Wisconsin were held to, including hunting and fishing regulations. In Stewart's opinion, Public Law 280 had no bearing on the case and the rights were not protected by the Termination Act, so they were lost. Stewart did note that this would have also made the claim for compensation valid under Shoshone Tribe v. United States, 299 U.S. 476 (1937)[30] regardless of whether Congress intended it or not. He would have reversed the decision of the Court of Claims.[1]

Subsequent developments

The case has been identified as one of the landmark cases in Native American law,[31][32] primarily in the area of reserved tribal rights.[33] It has been used in college courses to explain tribal sovereignty rights, even if the tribe has been terminated as the Menominee tribe was.[34][35][36] The opinion has been noted as a leading case in holding that the Federal government acted as a trustee, under normal trustee rules.[37] The case has even been discussed internationally (such as Australia), as to the relevance of indigenous or aboriginal title.[38]

Law reviews and journals

The case has been cited in over 200 law review articles as of September 2010.[39] A good number of these articles note that while Congress may terminate tribal and treaty rights, it must show a "specific intent to abrogate them."[40][41][42] It has also been pointed out that hunting and fishing rights are a valuable property right, and if the rights are taken away by the government, those holding those rights must be compensated for their loss.[40][43] Courts must also construe treaty rights and statutes liberally in favor of the Indians, even when the treaty does not specifically speak of hunting and fishing.[40][41][44]

Notes

- ^ The Dakota Indians are a sub-group of what is commonly known as the Sioux tribe.[11]

- ^ Commonly known as the Chippewa tribe.[12]

- ^ The Treaty of Washington did address the tribe's retained hunting and fishing rights.[8]

- ^ Commonly known as the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe, residing on the Stockbridge-Munsee Indian Reservation directly adjacent to the Menoninee Reservation. The Mahican (or Mohican) tribe is the tribe that James Fenimore Cooper used as the basis for the novel The Last of the Mohicans. The Lenape tribe is commonly known as the Delaware or Munsee. These two tribal groups united prior to their arrival in Wisconsin.[15]

- ^ Although the tribe owned the lumber operation and sawmill, these were managed by the BIA, with no tribal members being allowed in management positions.[21]

- ^ Unlike most of the world, the United States uses a multitude of local agencies, with approximately 20,000 police forces in the country.[22]

- ^ The plaintiffs included the Menominee tribe, Menominee Enterprises Inc., four tribal members, and the First Wisconsin Trust Co. (as trustee for the trust established by the termination act).[5]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Menominee Tribe v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968)

- ^ "Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin History". The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Keshena, WI: The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. June 22, 2010. http://www.menominee-nsn.gov/history/history.php. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Brose (1978). "Late Prehistory of the Upper Great Lakes Area". In Sturtevant, William C.. Handbook of North American Indians. 15 Northeast. Washington, DC: GPO. p. 578. ISBN 047000003512.

- ^ a b Treaty of St. Louis, 7 Stat. 153 (1817)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Menominee Tribe of Indians et al. v. United States, 388 F.2d 998 (Ct. Cl. 1967).

- ^ a b Treaty of Prairie du Chien, 7 Stat. 272 (1825)

- ^ a b Treaty of Butte des Morts, 7 Stat. 303 (1827)

- ^ a b Treaty of Washington, 7 Stat. 342 (1831) and 7 Stat. 405 (1832)

- ^ Treaty of Cedar Point, 7 Stat. 506 (1836)

- ^ Treaty of Lake Poygan, 9 Stat. 952 (1848)

- ^ Blevins, Winfred (2001). Dictionary of the American West: over 5,000 terms and expressions from Aarigaa! to Zopilote. Seattle, WA:Sasquatch Books. ISBN 9781570613043. p. 113

- ^ Gilman, Daniel Coit, Peck, Harry Thurston, and Colby, Frank Moore(1903). The New international encyclopædia, Volume 13. New York, NY:Dodd, Mead and Company. ISBN:None. p. 315

- ^ "MITW History – Chief Oshkosh". The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Keshena, WI: The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. September 22, 2009. http://www.menominee-nsn.gov/history/leaders/chiefOshkosh.php. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Treaty of Wolf River, 10 Stat. 1064

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick E. (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. New York, NY:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780395669211. p. 611.

- ^ Peroff, Nicholas C. (2006). Menominee Drums: Tribal Termination And Restoration, 1954–1974. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 52–77. ISBN 9780806137773.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Verna (2006). "Chapter 1.12: Termination and Restoration". In Tigerman, Kathleen. Wisconsin Indian literature: anthology of native voices. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780299220648.

- ^ DRUMS Committee, Menominee (2006). "Chapter 1.14: Menominee Termination". In Tigerman, Kathleen. Wisconsin Indian literature: anthology of native voices. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780299220648.

- ^ a b "Public Law 399, Chapter 303, June 17, 1954, H.R. 2828, 68 Stat. 250". Oklahoma State University Library. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/Vol6/html_files/v6p0620.html. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Peroff, Nicholas C. (2006). Menominee Drums: Tribal Termination And Restoration, 1954–1974. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 78–127. ISBN 9780806137773.

- ^ a b c Lurie, Nancy Oestreich (2002). Wisconsin Indians (2nd ed.). Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society. pp. 53–57. ISBN 9780870203305.

- ^ "Police: Organization and Management - The American System Of Policing". Law Library - American Law and Legal Information. Net Industries. http://law.jrank.org/pages/1668/Police-Organization-Management-American-system-policing.html. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Wunder, John R. (1996). The Indian Bill of Rights, 1968. Florence, KY: Taylor & Francis. p. 130. ISBN 9780815324874.

- ^ a b c d e f State v. Sanapaw, 124 N.W.2d 41 (Wis., 1963)

- ^ Sanapaw v. Wisconsin, 377 U.S. 991 (1964)

- ^ Indian Claims Commission Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1505 (1964)

- ^ Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1491 (1964)

- ^ The Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 95 Ct.Cl. 232 (Ct.Cl., 1941)

- ^ Public Law 280, 18 U.S.C. § 1162

- ^ Shoshone Tribe v. United States, 299 U.S. 476 (1937)

- ^ National Indian Law Library; American Association of Law Libraries (2002). Landmark Indian law cases. Buffalo, NY: Wm. S. Hein Publishing. pp. 177–184. ISBN 9780837701578.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce Elliott (1998). The encyclopedia of Native American legal tradition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 189–190. ISBN 9780313301674.

- ^ Wilkens, David E.; Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (2002). Uneven ground: American Indian sovereignty and federal law. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 133. ISBN 9780806133959.

- ^ Kidwell, Clara Sue; Velie, Alan R. (2005). Native American studies. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780803278295.

- ^ Thompson, William Norman (2005). Native American issues: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 63. ISBN 9781851097418.

- ^ Wilkenson, Charles F. (1988). American Indians, time, and the law: native societies in a modern constitutional democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780300041361.

- ^ Kidd, Rosalind (2006). Trustees on trial: recovering the stolen wages. Canberra, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780855755461.

- ^ Dorsett, Shaunnagh; Godden, Lee (1998). A guide to overseas precedents of relevance to native title. Canberra, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780855753375.

- ^ LexisNexis staff (September 4, 2010). "LexisNexis Academic". Reed Elsevier. http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/?. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c Esra, Jeri Beth K. (1989), "The Trust Doctrine: a Source of Protection for Native American Sacred Sites," 38 Cath. U.L. Rev. 705, Catholic University

- ^ a b Staff (1994), "Reaffirming the Guarantee: Indian Treaty Rights to Hunt and Fish Off-Reservation in Minnesota," 20 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 1177, William Mitchell Law Review

- ^ Laurence, Robert (1984), "Thurgood Marshall's Indian Law Opinions," 27 How. L.J. 3, Howard University

- ^ Reynolds, Laurie (1984), "Indian Hunting and Fishing Rights: the Role of Tribal Sovereignty and Preemption," 62 N.C. L. Rev. 743, University of North Carolina

- ^ Verhoeven, Charles K. (1987), "South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe: Terminating Federal Protection with "Plain" Statements," 72 Iowa L. Rev. 1117, University of Iowa

External links

Categories:- 1968 in United States case law

- Native American tribes in Wisconsin

- United States Native American treaty case law

- United States Supreme Court cases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.