- Baikal seal

-

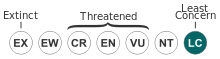

Baikal seal Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Phocidae Genus: Pusa Species: P. sibirica Binomial name Pusa sibirica

Gmelin, 1788

Baikal Seal range Synonyms Phoca sibirica The Baikal seal, Lake Baikal seal, or Nerpa (Pusa sibirica, obsolete: Phoca sibirica), is a species of earless seal endemic to Lake Baikal in Siberia. Like the Caspian seal, they are related to the Arctic ringed seal. The Baikal Seal is the smallest of the true seals, and with the exception of a sub-population of inland harbour seals living in the Hudson Bay region of Quebec, Canada (lac de loups marins harbour seals), they are the only exclusively freshwater pinniped species.[2]

It remains a scientific mystery how the seals originally came to Lake Baikal, hundreds of kilometers from any ocean. Some scientists speculate the seals arrived at Lake Baikal when a sea-passage linked the lake with the Arctic Ocean (see also West Siberian Glacial Lake and West Siberian Plain).

The total population is estimated to be over 60,000 animals, and hunting of the seals, once widespread, is now restricted.[citation needed]

Contents

Statistics

- Weight: 70 kg (155 lb) average, 150 kg (330 lb) maximum

- Length: 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) average

- Food: mainly golomyanka and goby

- Litter: usually one pup, sometimes two

- Diving time: usually 20–25 minutes (45–60 minutes maximum)

Description

The Baikal seal is one of the smallest true seals. The adult grows to be around 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) in length with body mass from 63 to 70 kg (140 to 155 lb).[3] The animals show very little sexual dimorphism; the males are only slightly larger than the females.[3] They have a uniform steely-grey coat on their backs and fur with a slightly more yellow tinge coating their abdomens. As the coat weathers, it becomes brownish.[4] When first born, pups are around 4.5 kg (10 lb) and have a coating of white silky natal fur. This fur is quickly shed and exchanged for a darker coat, much like that of the adult. Rare Baikal seals can be found with spotted coats.[3]

Distribution

The Baikal seal lives only in the waters of Lake Baikal.[5] It is something of a mystery how Baikal seals came to live there in the first place. It can be speculated they swam up rivers and streams or possibly Lake Baikal was linked to the ocean at one point as the result of a large body of water, such as the West Siberian Glacial Lake or West Siberian Plain, formed in a previous ice age. No one knows, but it is estimated seals have inhabited Lake Baikal for some two million years. The Baikal seal, the Saimaa Ringed Seal (Pusa hispida saimensis), and the Ladoga seal (Pusa hispida ladogensis) are the only exclusively freshwater seals.

The areas of the lake in which the Baikal seals reside changes depending on the season as well as some other environmental factors. Baikal seals are solitary animals for the majority of the year, sometimes living kilometers away from other Baikal seals. In general, there is a higher concentration of Baikal seals in the northern parts of the lake, because the longer winter keeps the ice frozen for longer, which is preferable for pupping.[4] However, in recent years there have been migrations to the southern half of the lake. These are speculated to evade hunters.[3] In winter, when the lake is frozen over, seals maintain a few breathing holes over a given area and tend to remain nearby, not interfering with the food supplies of a nearby neighbour. When the ice begins to melt, the Baikal seals tend to keep to the shoreline.

Abundance and trends

As of 2007, the Baikal seal is listed as a “lower risk” species on conservation lists.[3] This means that while they are not currently threatened or endangered, it is possible and even likely they will be in the near future. At last official count, by the Russian government in 1994, they numbered 104,000. In 2000, Greenpeace performed its own count and came up with somewhere from 55,000 to 65,000 seals.[5] It is thought[who?] excessive hunting, as well as less severe problems of poaching and pollution, are quickly reducing the population.

In the last century, the kill quota for hunting Baikal seals was raised several times, most notably after the fur industry boomed in the late 1970s and when official counts began indicating there were more Baikal seals than previously known.[4] The quota in 1999 was 6,000, lowered in 2000 to 3,500 which is still nearly 5% of the Baikal Seal population if the Greenpeace count is correct.[3] In addition, new techniques, such as netting breathing holes, and seal dens to catch pups have been introduced. In one area, 3,000 out of 4,000 breathing holes had been netted, many probably illegally.[citation needed] One prime seal pelt will bring 1,000 rubles at market, more than a month’s salary.[5]

Lake Baikal has eight wildlife patrol officers, which amounts to one officer for roughly 2,500 square kilometers, making enforcement of regulations difficult. Even without poaching, hunting, even on a small quota, is a problem, because many of the seals that are shot or injured still escape, and die later. These do not fall under the kill quota and are tacked on after. It is unlikely poaching and hunting will slow considerably without government intervention.

The other problem at Lake Baikal is the introduction of pollutants into the ecosystem. Pesticides such as DDT and Hexachlorocyclohexane, as well as industrial waste, mainly from the Baikalisk pulp and paper plant, have thought to have been the cause of several disease epidemics among the Baikal Seal. The speculation is that the chemicals work their way up the food chain, and weaken the Baikal seal's immune systems, making them susceptible to diseases such as canine distemper and the plague, which was the cause of a serious Baikal seal epidemic that resulted in the deaths of thousands of animals in 1997 and 1999.[3]

Reproduction

Female Baikal seals reach sexual maturity at 3–6 years of age, whereas males reach it around 4–7 years.[3] The males and females are not strongly sexually dimorphic. Baikal seals mate in the water towards the end of the pupping season. With a combination of delayed implantation and a 9-month gestation period, the Baikal seal’s overall pregnancy is around 11 months. Pregnant females are the only Baikal seals to haul out during the winter. The males tend to stay in the water, under the ice, all winter. Baikal seals usually give birth to one pup, but they are one of only two species of true seal with the ability to give birth to twins. The twins will often stick together for some time after being weaned. The females, after giving birth to their pups on the ice in late winter, will become immediately impregnated again, and will often be lactating while pregnant.

Baikal seals are slightly polygamous and slightly territorial, although not particularly defensive of this territory. Males will mate with around 3 females if given the chance. They then mark the female’s den with a strong musky odor, which can be smelled by another male if he approaches. The female raises the pups on her own; she will dig them a fairly large den under the ice, up to 5 m (16 ft) )in length, and more than 2 m (6 ft) wide. Pups as young as two days old will then further expand this den by digging a maze of tunnels around the den. Since the pup will avoid breaking the surface with these tunnels, it is thought that this activity is mainly for exercise, to keep warm until they have built up an insulating layer of blubber.

The mother Baikal seal will feed her young for around 2.5 months, nearly twice as long as any other seal. During this time, the pups can increase their birth weight (around 4 kg {9 lb}) fivefold. After the pups are weaned, the mother will introduce them to solid food, bringing shrimp, fish, and other edibles into the den.

In spring, when the ice melts and the dens usually collapse, the pup is left to fend for itself. Growth continues until they are 20 to 25 years old.

Every year in the late winter and spring, both sexes will haul themselves out and begin to moult their coat of fur from the previous year, which will be replaced with a new one. While moulting they do not eat and enter a lethargic state, during which time they often die of overheating, males especially, from lying on the ice too long in the sun.[4] During the spring and summer, groups as large as 500 can form on the ice floes and shores of Lake Baikal. Baikal seals can live to over 50 years old, exceptionally old for a seal, although they are presumed to be fertile only until they are around 40.[4]

Foraging

The Baikal seal’s main food source is the golomyanka, found only in Lake Baikal. Baikal seals eat more than half of the annual produced biomass of golomyanka, some 64,000 tons.[4] Baikal seals also eat some types of invertebrates,[4] and the occasional omul. They feed mainly at night, when the fish come within 100 m (330 ft) of the surface. They feed with 10-20 minute dives, although this is hardly the extent of their abilities. Baikal seals have two liters more blood than any other seal of their size and can stay underwater for up to 70 minutes if they are frightened or need to escape danger.

The Baikal seal is blamed for drops in omul numbers; however, this is not the case. The omul’s main competitor is the golomyanka and by eating tons of these fish a year, Baikal seals cut down on the omul’s competition for resources.[4]

Baikal seals do have one unusual foraging habit. In the early autumn, before the entire lake freezes, they migrate to bays and coves and hunt sculpin, a fish that lives in silty areas and as a result usually contains a lot of grit and silt in its stomach. This grit scours out the seal's innards and gets rid of parasites.[4]

See also

- List of solitary animals

Bibliography

- Peter Saundry. 2010. Baikal seal. Encyclopedia of Earth. topic editor: C. Michael Hogan; ed. in-chief: Cutler J. Cleveland. Washington, DC (Accessed May 21, 2010)

- Earth Island Institute. “The Lake Baikal Seal: Already Endangered” (on-line), Baikal Watch. (Accessed March 6, 2004; archive.org link added August 25, 2010.)

References

- ^ Burkanov, V. (2008). Pusa sibirica. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 29 January 2009.

- ^ Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. clapham, James A. Powell, "National Audubon Society Guide to the Marine Mammals of the World", Alfred A. Knopf publishing, New York, 2002

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Baikal Seal (Phoca Sibirica)". Seal Conservation Society. http://www.pinnipeds.org/species/baikal.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pastukhov, Vladimir, D.. "The Face of Baikal - Nerpa". Baikal Web World. http://www.bww.irk.ru/baikalseals/baikalseals_01.html. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b c Schofield, James (27 July 2001). "Lake Baikal’s Vanishing Nerpa Seal". The Moscow Times. http://www.themoscowtimes.com/stories/2001/07/27/106.html. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

External links

- Harrold, A. 2002. “Phoca Sibirica” (on-line), Animal Diversity Web. (Accessed August 27, 2007.)

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- True seals

- Wildlife of Siberia

- Lake Baikal

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.