- Normansville, New York

-

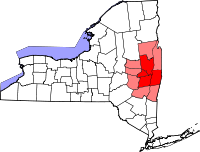

Normansville Hamlet Formerly: Upper Hollow Name origin: For being a village along the banks of the Normans Kill (creek) Country United States State New York Region Capital District County Albany Municipality Town of Bethlehem and City of Albany River Normans Kill Coordinates 42°38′01″N 73°47′57″W / 42.63361°N 73.79917°W Timezone EST (UTC-5) - summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP Code 12054 (Bethlehem side)/12209 (Albany side) Area code 518 Normansville is a hamlet in the town of Bethlehem and a neighborhood in the city of Albany, Albany County, New York. The entire area was one hamlet in Bethlehem until the portion north of the Normans Kill was annexed by Albany in 1916. The Delaware Turnpike once ran through both neighborhoods until 1929 with the construction of a new much higher, longer, and wider Delaware Avenue Bridge over the Normans Kill. This allowed commuters to and from Albany to bypass both Normansvilles. The original lower bridge still stands, though it has been closed to vehicular traffic since January 1990.

Contents

History

Normansville was originally called Upper Hollow for the deep ravine carved by the Normans Kill that the unincorporated village sits in. Further downstream was Lower Hollow, later named Kenwood. Upper Hollow had its start with the construction of the Delaware Turnpike in 1805 which went from the city of Albany to Otego (which then was part of Delaware County).[1] At the Normans Kill (kill is Dutch for stream) the road was carried by a 100-foot-long (30 m) wooden bridge and northwest of this bridge was a toll-gate. This bridge was washed away by a freshet in 1869. [2] This was the year after the turnpike company had abandoned the road and so the town of Bethlehem built an iron bridge in its place.[1][2]

Soon after the turnpike was constructed taverns and various industries began to spring up to take advantage of the power that could be harnessed from the Normans Kill's waters. Among the industries were cloth mills and saw mills, several of these mills were swept aside by the same freshet that washed away the bridge, they were quickly rebuilt but by the beginning of the 20th century the mills were abandoned.[2] Another major industry along the Normans Kill was that of cutting ice blocks from the creek during the winter and storing it for shipping to New York City and other locations for use in iceboxes. The Pappalau Ice House on the Albany side was one of many ice houses along the Normans Kill and Hudson River at the end of the 1800s, by 1920 it too would be abandoned as new technologies made the industry obsolete. [3]

In 1916 Albany annexed much of the town of Bethlehem up to the Normans Kill. This included that portion of the hamlet of Normansville north of the creek. Prior to this annexation the children of Normansville attended a small school, Bethlehem District Number 11 in Normansville on the Delaware Turnpike. After the annexation those children in Albany attended the city schools, and the children remaining in Bethlehem continued to attend school in District 11. Due to the annexation and the loss of a large amount of the taxable land, the district was consolidated into neighboring District Number 7 in 1919.[4]

In 1929 Delaware Avenue was rerouted and a wider, higher, longer highway bridge called the Normanskill Viaduct was built across the top of the Normans Kill ravine.[5] Starting in the spring of 1994 the Normanskill Viaduct was dismantled and replaced by a new bridge 50 feet upstream.[6]

In the 1980s several changes occurred to the sleepy hamlet, especially on the Bethlehem side. In 1986 the original yellow brick turnpike road was paved over, the yellow bricks were first pulled up and saved though.[7] Rockefeller Road, the main street on the Bethlehem side, was the main route south out of the hamlet and connected to Kenwood Avenue by way of a bridge built in 1914 over the now-abandoned Delaware and Hudson Railroad tracks. In 1987 the town closed the Rockefeller Road Bridge due to safety concerns, this was supported by the Normansville Neighborhood Association to remove the traffic that used Rockefeller Road as a shortcut between Kenwood and Delaware avenues.[8] In January 1990 the older Normans Kill bridge was closed to vehicular traffic, and since then the two Normansvilles have had little exchange even though pedestrian travel over the bridge is still possible. Since then Old Delaware Avenue to Delaware Avenue is the only way in and out of Bethlehem's Normansville.[9][10]

Demographics

In 1886 the hamlet (including both sides of the Normans Kill) had roughly 100 individuals, 22 families, and 17 dwellings.[2] Over 100 years later in 1993 it was estimated that the hamlet on the Bethlehem side consisted of 50 people, 19 homes, and one church.[6]

Geography

Normansville lies within and along the banks of a ravine. This ravine was carved by the Normans Kill, a creek and tributary of the Hudson River that forms the border between the city of Albany to the north and the town of Bethlehem to the south. The ravine is of clay banks with the creek flowing over a bed of slate.[2]

Location

City of Albany

Normans Kill

Hamlet of Elsmere

Graceland Cemetery  Hamlet of Normansville

Hamlet of Normansville

Landmarks

Whipple truss bridge at the Steven's Farm. It is on the National Register of Historic Places

Whipple truss bridge at the Steven's Farm. It is on the National Register of Historic Places

- Steven's Farm – Also called Normanskill Farm, a city-owned park and active farm. The park has the largest of Albany's community gardens, a dog park, hiking trails, a working farm, historic farm buildings, and a historic whipple truss bridge from 1867.[11][12] The Albany Mounted Police Unit's draft horses are also kept here.[13] The domesticated ducks and geese that call Washington Park home are brought to Stevens Farm every year for winter accommodations.[14]

- Old Normans Kill Bridge – Original bridge across the Normans Kill, over 60 feet below the current Normanskill Viaduct.[6] The bridge, built in 1884, is 158 feet long, paved with yellow bricks, and barely wide enough for two cars to pass.[10] Local legend states that Edgar Allan Poe wrote about the yellow bricks the road and bridge were paved with and this was picked up by L. Frank Baum who used this reference in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Local historians stress this has not been confirmed and is just local lore.[6][15]

See also

- History of Albany, New York

- Neighborhoods of Albany, New York

References

- ^ a b George Howell and Jonathan Tenney (1886). Bi-Centennial History of Albany: History of the County of Albany from 1609-1886; Volume 2. W.W. Munsell and Company. p. 790. http://books.google.com/books?id=nWkJAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA940&dq=lisha's+kill&cd=5#v=onepage&q=lisha's%20kill&f=false. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ^ a b c d e George Howell and Jonathan Tenney (1886). Bi-Centennial History of Albany: History of the County of Albany from 1609-1886; Volume 2. W.W. Munsell and Company. pp. 781–2. http://books.google.com/books?id=nWkJAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA940&dq=lisha's+kill&cd=5#v=onepage&q=lisha's%20kill&f=false. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ^ "Town of Bethlehem, NY History". Town of Bethlehem. http://www.townofbethlehem.org/pages/about/history.asp. Retrieved 2010-02-25.[dead link]

- ^ William V.R. Erving (1920). Department Reports of the State of New York Containing the Messages of the Governor and the Decisions, Opinions and Rulings of the State Officers, Departments, Boards and Commissions; Volume 22. J.B. Lyon Company. pp. 300–301. http://books.google.com/books?id=LHJMAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA300&dq=laws+of+the+state+of+new+york+1916+albany+bethlehem&lr=&cd=7#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Trees and Faces Both Fall Over Bridge Construction". Albany Times Union. April 6, 1994. p. B3. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5692311. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ a b c d Rick Karlin (April 18, 1993). "A Bridges Moves Atop Tiny Normansville". Albany Times Union. p. H1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5664083. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Barbara Hayden (September 24, 1989). "Normansville Resident Charts Past Hamlet Once Thriving Center of Homes, Commerce". Albany Times Union. p. B10. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5522272. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Normansville Group Against Span Reopening". Albany Times Union. October 28, 1987. p. 6A. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5443997. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Christopher Ringwald (July 10, 1996). "The Current Slows in Normansville". Albany Times Union. p. B1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5821602. Retrieved 2010-02-38.

- ^ a b Barbara Hayden (February 17, 1990). "History or Economy Closed Bridge a Sore Spot in Normansville". Albany Times Union. p. B6. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5553218. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Deborah Gesensway (May 9, 1988). "Albany Grows on City Farmers". Albany Times Union. p. A1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5486373. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Brian Nearing (August 6, 2004). "Old Iron Bridge Showing its Age". Albany Times Union. p. B1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=6247813. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Frances Ingraham (September 22, 2002). "Riding the Beat Albany's Mounted Police Form a Special Bond With Their Equine Partners". Albany Times Union. p. G1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=6135980. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Lake to be Drained to Fix Sewer Line". Albany Times Union. November 18, 1995. p. B4. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5749084. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Rick Karlin (July 6, 1995). "Bridge Legends Run Deep and Wide". Albany Times Union. p. C1. http://archives.timesunion.com/mweb/wmsql.wm.request?oneimage&imageid=5778440. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

Additional reading

- Michael Lisa (June 21, 2009). "Neighborhoods: Normansville, Bethlehem". Albany Times Union. p.G7.

- Dawn Padfield (September 1, 2009). "The Yellow Brick Road". All Over Albany (Uptown/Downtown Media).

Capital District of New York Central communities Albany (History · City Hall · Coat of Arms) · Schenectady (City Hall) · Troy (History) · List of all incorporated places

Largest communities

(over 20,000 in 2000)Medium-sized communities

(10,000 to 20,000 in 2000)City of Amsterdam · Brunswick · Cohoes · East Greenbush · Glens Falls · Gloversville · Halfmoon · Malta · North Greenbush · Schodack · Watervliet · WiltonSmall communities

(5,000 to 10,000 in 2000)Town of Amsterdam · Ballston Spa · Cobleskill · Village of Colonie · Duanesburg · City of Johnstown · Town of Johnstown · Kinderhook · Mechanicville · New Scotland · Rensselaer · Sand Lake · Scotia · Town of Stillwater · WaterfordCounties Albany · Columbia · Fulton · Greene · Montgomery · Rensselaer · Saratoga · Schenectady · Schoharie · Warren · WashingtonHistory Mohawks · Mahicans · Fort Orange · Rensselaerswyck · Beverwyck · Albany Plan of Union · Timeline of town creation · Toponymies of places · Tech ValleyGeography Hudson River (Valley) · Mohawk River · Erie Canal · Lake Albany · Lake George · Albany Pine Bush (Rensselaer Lake · Woodlawn Preserve) · Adirondack Mountains · Catskill Mountains · Rensselaer PlateauReligion and culture Culture in New York's Capital District · Sports in New York's Capital District · Episcopal Diocese of Albany · Roman Catholic Diocese of AlbanyEducation Public school districtsList of school districts in New York's Capital DistrictHigher educationNewspapers TV/Radio Broadcast television in the Capital District Local stations WRGB (6.1 CBS, 6.2 This TV) • WTEN (10.1 ABC, 10.2 Weather, 10.3 RTV) • WNYT (13.1 NBC, 13.2 Weather, 13.3 Weather Radar) • WMHT (17.1 PBS, 17.2 ThinkBright, 17.3 HD) • WXXA (23.1 Fox, 23.2 The Cool TV) • WNGN-LP 35 / WNGX-LP 42 (FN) • WCWN (45.1 The CW, 45.2 Uni Sp) • WNYA / WNYA-CD (51.1 MNTV, 51.2 Antenna TV) • W52DF 52 (silent)

Outlying area stations WVBK-CA 2 (RSN' Manchester, VT) • W04AJ 4 (PBS; Glens Falls) • W04BD 4 (PBS; Schoharie) •

WNCE-CA 8 (A1; Glens Falls) • WYBN-CA 14 (RSN; Cobleskill) • WCDC (19.1 ABC; Adams, MA) • WVBG-LP 25 (RSN; Greenwich) • W36AX 36 (PBS / VPT; Manchester, VT) • W47CM 47 (silent; Glens Falls) • WYPX (55.1 Ion, 55.2 qubo, 55.3 Life; Amsterdam) • W53AS 53 (PBS / VPT; Bennington, VT)Adjacent locals Cable-only stations YNN Capital Region • TW3 • YES • SNY • MSG Network

Defunct stations New York State television: Albany/Schenectady • Binghamton • Buffalo • Burlington/Plattsburgh • Elmira • New York City • Rochester • Syracuse • Utica • Watertown

Vermont Broadcast television: Albany/Schenectady • Boston, MA • Burlington/Plattsburgh

Massachusetts television: Albany • Boston • Providence • Springfield

Radio stations in the Albany / Schenectady / Troy market by FM frequency 88.3 · 89.1² · 89.7 · 89.9 · 90.3/93.1² · 90.7/94.9 · 90.7 · 90.7 · 90.9 · 91.1 · 91.5 · 92.3 · 92.9 · 93.5 · 93.7 · 94.5 · 94.7 · 95.5 · 95.9 · 96.3 · 96.7 · 97.3 · 97.5 · 97.7 · 97.9 · 98.3² · 98.5 · 98.5 · 99.1 · 99.5² · 100.3 · 100.9 · 101.3 · 101.7 · 101.9 · 102.3² · 102.7 · 103.1² · 103.5 · 103.9 · 104.5 · 104.9 · 105.7² · 106.1 · 106.5² · 107.1 · 107.7²by AM frequency NOAA Weather Radio frequency 162.550by callsign W226AC · W235AY · W256BU · W291BY · WABY · WAJZ · WAMC (AM) · WAMC-FM² · WBAR · WBPM · WCDB · WCKL · WCKM · WCQL · WCSS · WCTW · WDCD · WDCD-FM · WDDY² · WENT · WEQX · WEXT · WFFG · WFLY · WFNY · WGDJ · WGNA² · WGXC · WGY¹² · WGY-FM² · WHAZ · WHAZ-FM · WHUC · WHVP · WIZR · WJIV · WKBE · WKKF² · WKLI · WLJH · WMHT² · WMYY · WNYQ · WOFX² · WOPG · WPGL · WPYX² · WQAR · WQBJ · WQBK · WQSH² · WRIP · WROW · WRPI · WRUC · WRVE² · WSDE · WTMM · WTRY² · WUAM · WVCR · WVKZ · WVTL · WXL34 · WYAI · WYJB · WYKV · WZCR · WZMRDefunct stations New York Radio Markets: Albany-Schenectady-Troy • Binghamton • Buffalo-Niagara Falls • Elmira-Corning • Hamptons-Riverhead • Ithaca • Nassau-Suffolk (Long Island) • New York City • Newburgh-Middletown (Mid Hudson Valley) • Olean • Plattsburgh • Poughkeepsie • Rochester • Syracuse • Utica-Rome • Watertown

Other New York Radio Regions: Jamestown-Dunkirk • North Country • Saratoga

See also: List of radio stations in New YorkMunicipalities and communities of Albany County, New York Cities Albany | Cohoes | Watervliet

Towns Berne | Bethlehem | Coeymans | Colonie | Green Island | Guilderland | Knox | New Scotland | Rensselaerville | Westerlo

Villages Altamont | Colonie | Green Island | Menands | Ravena | Voorheesville

CDPs Other

hamletsAlcove | Boght Corners | Clarksville | Crescent Station | Dunsbach Ferry | Elsmere | Feura Bush | Fort Hunter | Fullers | Glenmont | Guilderland | Guilderland Center | Karner | Latham | Lisha Kill | Loudonville | Mannsville | McKownville | New Salem | Newtonville | Normansville | Roessleville | Selkirk | Slingerlands | South Bethlehem | Verdoy | West Albany

Categories:- Bethlehem, New York

- Albany, New York

- Hamlets in New York

- Populated places in Albany County, New York

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.