- Missouri River

-

Missouri River Pekitanoui, River of the West, Yellow River[1] Part of the Missouri River in North DakotaName origin: The Missouria tribe, whose name in turn meant “people with wooden canoes”[1] Country  United States

United StatesStates Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri Tributaries - left Jefferson, Sun, Marias, Milk, James, Big Sioux, Grand, Chariton - right Madison, Gallatin, Yellowstone, Little Missouri, Cheyenne, White, Niobrara, Platte, Kansas, Osage, Gasconade Cities Great Falls, MT, Bismarck, ND, Pierre, SD, Sioux City, IA, Omaha, NE, Kansas City, KS, Kansas City, MO, St. Louis, MO Primary source Jefferson River - location Centennial Mountains, Montana - elevation 9,030 ft (2,752 m) - coordinates 44°33′01″N 111°28′20″W / 44.55028°N 111.47222°W [2] Secondary source Madison River - location Near Madison Junction, Teton County, Wyoming - elevation 8,215 ft (2,504 m) - coordinates 44°20′37″N 110°52′43″W / 44.34361°N 110.87861°W Source confluence Jefferson and Madison Rivers - location Three Forks, Montana - elevation 4,042 ft (1,232 m) - coordinates 45°55′39″N 111°20′39″W / 45.9275°N 111.34417°W [1] Mouth Mississippi River - location Spanish Lake, near St. Louis, Missouri - elevation 404 ft (123 m) [1] - coordinates 38°48′49″N 90°07′11″W / 38.81361°N 90.11972°W [1] Length 2,341 mi (3,767 km) [3] Basin 529,350 sq mi (1,371,010 km2) [4] Discharge for Hermann, MO; RM 97.9 (RKM 157.6) - average 86,340 cu ft/s (2,445 m3/s) [5] - max 712,200 cu ft/s (20,167 m3/s) [6] - min 602 cu ft/s (17 m3/s) The Missouri River flows 2,341 miles (3,767 km) through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great Plains east of the Rocky Mountains, spanning parts of ten U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Cities along the main stem such as Great Falls, Sioux City, Omaha, Kansas City, and St. Louis are home to many of the basin's people. Measured from its farthest source in southwestern Montana to the Mississippi's mouth at the Gulf of Mexico, it forms part of the world's fourth-longest river system.

As early as 12,000 years ago, prehistoric Paleo-Indians arrived in the Missouri River basin. Prominent Native American tribes that lived on the river in immediate pre-Columbian times included the Mandan, Sioux, Hidatsa, Osage, and Missouria – the latter for whom the river is named. After the 17th century, European and American explorers began to wander the region, and the Missouri basin became part of France's Louisiana; when the United States acquired the territory, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled the river partly in search of the mythical Northwest Passage. Later in the 19th century, the westward movement of American pioneers pushed Native Americans out of their traditional lands, leading to wars. The Missouri defined the American frontier in the 19th century, and many prominent westward routes, the Oregon Trail among them, followed the river and its tributaries.

Once, the Missouri River was by far the longest river of North America; today however, the Missouri is only slightly longer than the Mississippi. This is due, in large part, to many of the Missouri River's meanders being cut to facilitate navigation. The lower Missouri valley has become a highly productive agricultural and industrial region, and barges shipping grown and manufactured products provide most of today's river commerce. In the 20th century, federal and state agencies including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) heavily dammed and channelized the river. Although all of this development has contributed to the region's economic growth, it has taken a toll on the ecology and the water quality of the Missouri.

Contents

Course

From the Rockies of southwestern Montana, three streams rise to form the headwaters of the Missouri River. The longest begins at Brower's Spring, 9,030 feet (2,750 m) above sea level, on the northern flank of the Centennial Mountains. Flowing west then north, it flows first in Hell Roaring Creek, then west into the Red Rock; swinging northeast to become the Beaverhead, it finally joins with the Big Hole to form the Jefferson. The Gibbon and Firehole rivers flow together to form the Madison River, similar in size to the Jefferson. Along with the smaller Gallatin River, the Madison emerges from Yellowstone National Park in northwestern Wyoming, flowing north and northwest into Montana.[7][8]

The Missouri River officially starts at the confluence of the Jefferson and Madison in Missouri Headwaters State Park near the town of Three Forks.[9] It flows north through small canyons, shortly being joined by the Gallatin, then passes through Canyon Ferry Lake, a reservoir west of the Big Belt Mountains. Issuing from the mountains near Cascade, the river flows northeast to the city of Great Falls, where it drops over the Great Falls of the Missouri, a series of five substantial waterfalls. The river then winds east through canyons and badlands of the Missouri Breaks, meeting the Marias River then widening into the Fort Peck Lake reservoir a few miles above the confluence with the Musselshell River. Farther on the river passes through the gates of the Fort Peck Dam, and immediately after that, the Milk River enters from the left.[7][8]

Flowing eastwards through the plains of eastern Montana, the Missouri receives the Poplar River from the north before crossing into North Dakota where the Yellowstone River, its greatest tributary by volume, joins from the right. At the confluence, the Yellowstone is actually the larger river.[n 1] The Missouri then meanders east past Williston and into Lake Sakakawea, a reservoir formed by the Garrison Dam, where the river turns south. South of Riverdale, the Knife River enters from the right. The Missouri continues south to Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, where it receives the Heart River. It slows into the Lake Oahe reservoir just before the Cannonball River confluence. While it continues south, eventually reaching Oahe Dam in South Dakota, the Grand, Moreau and Cheyenne Rivers all join the Missouri from the right.[7][8]

The Missouri makes a bend to the southeast as it winds through the Great Plains, receiving the Niobrara River and many smaller tributaries from the right. It then proceeds to form the boundary of South Dakota and Nebraska, then after being joined by the James River, forms the Iowa-Nebraska boundary. At Sioux City the Big Sioux River comes in from the left. The Missouri flows south to the big city of Omaha where it receives one of its largest tributaries, the Platte River. Downstream, it begins to define the Nebraska-Missouri border, then flows between Missouri and Kansas. The Missouri swings east at Kansas City, where the Kansas River enters from the right, and so on into north-central Missouri. It passes south of Columbia and receives the Osage River, its last major tributary, downstream of Jefferson City. The river then rounds the northern side of St. Louis to join the Mississippi River on the border between Missouri and Illinois.[7][8]

Watershed

There is only one river with a personality, a sense of humor, and a woman's caprice; a river that goes traveling sidewise, that interferes in politics, rearranges geography, and dabbles in real estate; a river that plays hide and seek with you today and tomorrow follows you around like a pet dog with a dynamite cracker tied to his tail. That river is the Missouri.

-George Fitch, circa 1840[12]With a drainage basin spanning 529,350 square miles (1,371,000 km2),[4] the Missouri's catchment encompasses nearly one-sixth of the area of the United States[13] or just over five percent of the continent of North America.[14] The mostly flat, arid basin, comparable to the size of the Canadian province of Quebec, encompasses most of the northern Great Plains, stretching over 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Mississippi River valley in the east. From north to south it reaches well over 1,600 miles (2,600 km), from the southern extreme of western Canada in the north to the Arkansas River valley of the south. Compared with the Mississippi River above their confluence, the Missouri is actually much longer (150%) and drains a far greater area (309%). However, the flow of the Missouri at the confluence accounts for only 45 percent of the total amount of water below the meeting of the rivers.[5][15]

The Missouri River (background) near Niobrara, Nebraska, with marshes of a tributary, Niobrara River, in foreground

Although vast, the Missouri River watershed is home to only about ten million people,[4] living in all of the U.S. state of Nebraska, parts of the U.S. states of Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, and small southern portions of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.[4] The watershed's largest city is Denver, Colorado, with a population of just over 600,000. Significant tributary systems within the basin include the Milk and Yellowstone in the northwest, the James and Osage of the east, and the Platte and Kansas-Republican/Smoky Hill drainages of the southwestern plains. The Platte is the longest tributary, but the Yellowstone River is the largest tributary by discharge (in fact the Yellowstone's flow is about 13,800 cu ft/s (390 m3/s)[16] while the Platte averages a comparatively mere 7,000 cu ft/s (200 m3/s)[17]).

Elevations in the watershed vary widely from just over 400 feet (120 m) at the Missouri's mouth[1] to the high-altitude prairie of South Park in central Colorado.[18] The river itself drops from about 9,000 feet (2,700 m) in elevation at Brower's Spring, the farthest source. Although the plains of the watershed have extremely little local vertical relief, there is a definite slope from west to east; the land is roughly 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level at the base of the Rockies, but less than 500 feet (150 m) at the border of the Mississippi valley.[8]

As one of the continent's most important rivers,[19] the Missouri's drainage basin borders on many other major watersheds of the United States and Canada. The Columbia River and Colorado River systems drain the area west of the Rocky Mountains; however, in Wyoming, between the Missouri and Colorado watersheds there is an endorheic drainage called the Great Divide Basin, that is sometimes counted within the Missouri basin.[20] On the north low divides separate it from the Saskatchewan and Red River of the North, as well as several large endorheic areas in southern Alberta, Saskatchewan and northeastern North Dakota. On the east it is bordered by the upper Mississippi River and its western tributaries, and to the south by the Arkansas and White watersheds.[19]

Major tributaries

Main article: List of tributaries of the Missouri RiverOver 95 major tributaries and hundreds of smaller ones feed the Missouri River, with most of the larger ones coming in as the river draws close to the mouth.[21] The largest by discharge are the Yellowstone, Osage, Kansas and Platte. On the other end of the scale is the tiny Roe River in Montana, which at 201 feet (61 m) long is commonly held to be the world's shortest river.[22] Tributaries of the Missouri River over 40 miles (64 km) long[8] are listed going downstream also noting the state in which they enter.

The longest tributaries of the Missouri, as measured from the mouth to the farthest source (regardless of naming changes), are listed in the below table in addition to their respective drainage basins and discharges.

Statistics of the Missouri's ten longest tributaries  Yellowstone River, the largest tributary, which enters in North Dakota

Yellowstone River, the largest tributary, which enters in North Dakota

Tributary Length Drainage basin Discharge Platte River 1,025 mi

(1,650 km)[23][n 2]84,910 mi2

(219,900 km2)[24]7,037 cuft/s

(199 m3/s)[17]Kansas River 779 mi

(1,250 km)[23][25][n 3]59,500 mi2

(154,100 km2)[24]7,367 cuft/s

(209 m3/s)[26]Milk River 729 mi

(1,170 km)[25]15,300 mi2

(39,630 km2)[24]618 cuft/s

(17.5 m3/s)[27]James River 710 mi

(1,140 km)[25]21,500 mi2

(55,680 km2)[24]646 cuft/s

(18.3 m3/s)[28]Yellowstone River 702 mi

(1,130 km)[8][29]70,000 mi2

(181,300 km2)[24]13,800 cuft/s

(391 m3/s)[16]White River 580 mi

(933 km)[25]10,200 mi2

(26,420 km2)[30]570 cuft/s

(16.1 m3/s)[30]Little Missouri River 560 mi

(901 km)[25]9,550 mi2

(24,730 km2)[24]533 cuft/s

(15.1 m3/s)[31]Osage River 493 mi

(793 km)[8][n 4]14,800 mi2

(38,330 km2)[24]11,980 cuft/s

(339 m3/s)[32]Niobrara River 430 mi

(692 km)[25]13,900 mi2

36,000 km2)[24]1,720 cuft/s

(48.7 m3/s)[33]Cheyenne River 347 mi

(558 km)[25]24,300 mi2

(62,940 km2)[24]874 cuft/s

(24.7 m3/s)[34]Flow

Fort Calhoun Nuclear Generating Station surrounded by the 2011 Missouri River Floods on June 16, 2011

By discharge, the Missouri is the ninth largest river of the United States, after the Mississippi, St. Lawrence, Ohio, Columbia, Niagara, Yukon, Detroit, and St. Clair (though the latter two are often considered part of a strait between Lake Huron and Lake Erie).[35] Among rivers of North America as a whole, it is thirteenth largest, after the Mississippi, Mackenzie, St. Lawrence, Ohio, Columbia, Niagara, Yukon, Detroit, St. Clair, Fraser, Slave, and Koksoak.[35][36]

As the Missouri drains a predominantly semi-arid region, its discharge is much less than rivers of comparable length such as the Mackenzie or Yukon. The average flow of 86,340 cubic feet per second (2,445 m3/s)[5] divided by the size of the drainage basin works out to an average discharge of about 0.16 cubic feet per second (0.0045 m3/s) per square mile. Due to the large size and dryness of the basin, flows also fluctuate significantly from year to year. The highest annual mean was 181,800 cubic feet per second (5,150 m3/s) in 1993, and the lowest was 41,690 cubic feet per second (1,181 m3/s) in 2006.[5] Extremes of the flow vary even further. The largest discharge ever recorded was over 710,000 cubic feet per second (20,000 m3/s) on July 31, 1993 during a historic flood.[37] The lowest, a mere 602 cubic feet per second (17.0 m3/s), was measured on December 23, 1963.[5]

Missouri River monthly discharges at Hermann, MO[38]

First row indicates discharge in cfs; second row in m3/s 52400 67900 96300 119000 125000 124000 101000 73600 75400 76500 76000 61000 1484 1923 2727 3370 3540 3511 2860 2084 2135 2166 2152 1727 Missouri River average discharges at selected cities

First row indicates discharge in cfs; second row in m3/s 10326 26500 28670 32190 54820 67160 86340 292 750 812 912 1552 1902 2445 Geology

High silt content makes the Missouri River (left) noticeably lighter than the Mississippi River here at their confluence north of St. Louis.

High silt content makes the Missouri River (left) noticeably lighter than the Mississippi River here at their confluence north of St. Louis.

The Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana at the headwaters of the Missouri River first rose in the Laramide Orogeny, a mountain-building episode that occurred from around 70 to 45 million years ago (the end of the Mesozoic through the early Cenozoic).[45] This orogeny uplifted Cretaceous rocks along the western side of the Western Interior Seaway, a vast shallow sea that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, and deposited the sediments that now underlie much of the drainage basin of the Missouri River.[46][47][48] This Laramide uplift caused the sea to retreat and laid the framework for a vast drainage system of rivers flowing from the Rocky and Appalachian Mountains, the predecessor of the modern-day Mississippi watershed.[49][50][51] The Laramide Orogeny is essential to modern Missouri River hydrology, as snow and ice melt from the Rockies provide the majority of the flow of the Missouri and its tributaries.[52]

The Missouri and many of its tributaries cross the Great Plains, flowing over or cutting into the Ogallala Group and older mid-Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. The lowest major Cenozoic unit, the White River Formation, was deposited between approximately 35 and 29 million years ago[53][54] and consists of claystone, sandstone, limestone, and conglomerate.[54][55] Channel sandstones and finer-grained overbank deposits of the fluvial[56] Arikaree Group were deposited between 29 and 19 million years ago.[53] The Miocene-age Ogallala and the slightly younger Pliocene-age Broadwater Formation deposited atop the Arikaree Group, and are formed from material eroded off of the Rocky Mountains during a time of increased generation of topographic relief;[53][57] these formations stretch from the Rocky Mountains nearly to the Iowa border and give the Great Plains much of their gentle but persistent eastward tilt, and also constitute a major aquifer.[58]

Immediately prior to the Quaternary Ice Age, the Missouri River was likely split into three segments: an upper portion that drained northwards into Hudson Bay,[59][60] and middle and lower sections that flowed eastward down the regional slope.[61] As the Earth plunged into the Ice Age, a pre-Illinoian (or possibly the Illinoian) glaciation diverted the Missouri River southeastwards towards its present confluence with the Mississippi and caused it to integrate into a single river system that cuts across the regional slope.[62] In western Montana, the Missouri River is surmised to have once flowed north then east around the Bear Paw Mountains. Sapphires are found in some spots along the river in western Montana.[63][64] Advances of the continental ice sheets diverted the river and its tributaries, causing them to pool up into large temporary lakes such as Glacial Lakes Great Falls, Musselshell and others. As the lakes rose the water in them often spilled across adjacent local drainage divides, creating now-abandoned channels and coulees including the Shonkin Sag, 100 miles (160 km) long. When the glaciers retreated, the Missouri flowed in a new course along the south side of the Bearpaws and the lower part of the Milk River tributary took over the original main channel.[65]

Nicknamed the “Big Muddy”, the Missouri certainly lives up to this name, transporting 20-25 million short tons (18-23 million t) of sediment per year. Before the construction of dams and levees, this load was many times higher, averaging 320 million short tons (290 million t) per year.[66] Much of this sediment is derived from the river’s floodplain, also called the meander belt; every time the river changed course, it would erode tons of soil and rocks from its banks. However, channeling and diking the river has kept it from reaching its natural sediment sources along most of its course. The creation of giant reservoirs has also trapped millions of tons of sediment since the 1940s. Despite this, the river still transports more than half the total silt that empties into the Gulf of Mexico; the Mississippi River Delta, formed by sediment deposits at the mouth of the Mississippi, constitutes a majority of sediments carried by the Missouri.[67][68]

First peoples

See also: Plains IndiansArchaeological evidence, especially in Missouri, suggests that early humans have inhabited the Missouri River basin for at least 10,000 years. Although the exact time range of human occupation is much debated among historians, research in the 1920s suggested that man first made his presence here about 12,000 years ago, at the end of the Pleistocene.[69] During the end of the last glacial period, a great migration of humans began, traveling via the Bering land bridge from Eurasia into and throughout the Americas. As they traveled slowly over centuries, the Missouri River formed one of the main migration paths. For those that stayed in the Mississippi River basin, most settled in the Ohio Valley and the lower Mississippi Valley, but many, including the Mound builders, stayed along the Missouri, becoming the ancestors of the later indigenous peoples of the Great Plains.[70]

Karl Bodmer, A Mandan Village, c. 1840–1843

Karl Bodmer, A Mandan Village, c. 1840–1843

The Native Americans that lived along the Missouri had access to ample resources of food, water, and shelter. Many migratory animals inhabited the plains at the time, providing them meat, clothing, and other everyday items; there were also great riparian areas along the river's shorelines that provided them with natural herbs and staple foods.[71] No written records from the tribes and peoples of the pre-European period exist because they did not use writing. According to the writings of explorers, some of the major tribes along the Missouri River included the Otoe, Missouria, Omaha, Ponca, Brulé, Lakota, Sioux, Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Assiniboine, Gros Ventres and Blackfeet.[72]

Natives used the Missouri, at least to a limited extent, as a path of trade and transport. In addition, the river and its tributaries formed tribal boundaries. Lifestyles of the indigenous mostly centered around a semi-nomadic culture; many tribes would have different summer and winter camps. However, the center of Native American wealth and trade lay along the Missouri River in the Dakotas region on its great bend south.[73] A large cluster of walled Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara villages situated on bluffs and islands of the river was home to thousands, and later served as a market and trading post used by early French and British explorers, wanderers and fur traders.[74] Following the introduction of the horse to Missouri River tribes possibly from feral European-introduced populations, the natives' way of life changed dramatically. The use of the horse allowed them to travel greater distances, and thus facilitated hunting, communications and trade.[75][76]

Once, tens of millions of American bison (commonly called buffalo), one of the keystone species of the Great Plains and the Ohio Valley, roamed the plains of the Missouri River basin.[77] Most Native American groups in the basin relied heavily on the bison as a food source, and their hides and bones served to create other household items. In time, the species came to benefit from the indigenous peoples' periodic controlled burnings of the grasslands surrounding the Missouri, in order to clear out old and dead growth. However, after the arrival of Europeans in North America, both the bison and the Native Americans saw a rapid decline in population.[78] Hunting eliminated bison populations east of the Mississippi River by 1833 and reduced the numbers in the Missouri basin to a mere few hundred. Foreign diseases such as smallpox raged across the land, decimating Native American populations. Parts of the Missouri River ecosystem then crumbled with the sheer losses.[79]

Early explorers

Jolliet and Marquette

"While conversing about these monsters sailing quietly in clear and calm water, we heard the noise of a rapid into which we were about to run. I never saw anything more terrific, a tangle of entire trees from the mouth of the Pekistanoui with such impetuosity that one could not attempt to cross it without great danger. The commotion was such that the water was made muddy by it and could not clear itself.Pekitanoui is a river of considerable size, coming from the northwest, from a great distance; and it discharges into the Mississippi. There are many villages of savages along this river, and I hope by this means to discover the Vermillion or California Sea."

–the journal of Louis Jolliet, 1673[80][81]The first known Europeans to see the river were the French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette in 1673. Shortly after looking at Piasa petroglyph paintings on the bluffs above the Mississippi River near the present-day location of Alton, Illinois, they heard the Missouri rushing into the Mississippi. "Pekistanoui" or "Pekitanoui" was the Native American name that the explorers recorded for the Missouri. At the time, the Missouri was in flood, which made it look significantly larger than the main stem of the Mississippi.[80][82]

Marquette wrote that natives had told him that it was just a six-day canoe trip up the river, some 60 miles (97 km), where it would be possible to portage over to another river that would take people to what is now the state of California (which was definitely not true). Jolliet and Marquette never explored the Missouri beyond its mouth, and did not linger in the area for long.[80]

Bourgmont

The Missouri remained formally unexplored and uncharted until Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont wrote "Exact Description of Louisiana, of Its Harbors, Lands and Rivers, and Names of the Indian Tribes That Occupy It, and the Commerce and Advantages to Be Derived Therefrom for the Establishment of a Colony" in 1713 followed in 1714 by "The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River." In the two documents Bourgmont was the first to use the name "Missouri" to refer to the river, and he was to name many tributaries based on the Native American tribes that lived along them. However, it is unclear how far up the Missouri Bourgmont traveled. He is the documented first European discoverer of the Platte River. In his writings he described the blonde-haired Mandans, so it is possible that he made it as far north as their villages in central North Dakota.[83][84] The names and locations were used by cartographer Guillaume Delisle to create the first reasonably accurate map of the river.[85]

Bourgmont was living with the Missouria tribe at a village near present-day Brunswick, Missouri with his Missouria wife and son. He had been on the lam from French authorities since 1706, when he deserted his post as commandant of Fort Detroit after he was criticized by Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac for his handling of an attack by the Ottawa tribe in which a priest, a French sergeant and 30 Ottawa were killed.[86] Bourgmont had further infuriated the French by illegally trapping, and for immoral behavior when he showed up at French outposts with his Native American wife.[85] However, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, founder of Louisiana, said that rather than arresting Bourgmont they should decorate him with the Cross of St. Louis and name him "commandant of the Missouri" to represent France on the entire river. Bourgmont's reputation was further enhanced when the Pawnee, who had been befriended by Bourgmont, massacred the Spanish Villasur expedition in 1720[87] near modern day Columbus, Nebraska, which temporarily ended Spanish designs on the Missouri River and cleared the way for a New France empire stretching from Montreal, Canada to present-day New Mexico.[88]

After squabbling with French authorities over financing of a new fort on the Missouri and also suffering an yearlong illness, Bourgmont established Fort Orleans in late 1723. It was the first fort and first longer term European settlement of any kind on the Missouri River, situated near present day Brunswick in the north-central part of what is now the state of Missouri. In 1724 Bourgmont led an expedition to enlist Comanche support in the fight against the Spanish. The following year, he brought the chiefs of several Missouri River tribes to Paris to see the glory of France, including the palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau and a hunting expedition on a royal preserve with Louis XV. Bourgmont was raised to the rank of the nobility, remained in France and did not accompany the chiefs back to the New World. Fort Orleans was either abandoned or its small contingent was massacred by Native Americans in 1726.[89]

Mackay and Evans

The Spanish took over the Missouri River in the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the French and Indian War, the North American theater of the Seven Years' War.[90] The Spanish claim to the Missouri was based on Hernando de Soto's "discovery" of the Mississippi River on May 8, 1541. The Spanish initially did not extensively explore the river and let French fur traders continue their activities, although under license only. After the British began to exert influence on the upper Missouri River watershed through the Hudson's Bay Company, news of English incursions came following an expedition by Jacques D’Eglise in 1790.[91] The Spanish chartered the "Company of Discoverers and Explorers of the Missouri" (popularly referred to as the "Missouri Company") and offered a reward for the first person to reach the Pacific via the Missouri. In 1794 and 1795 expeditions led by Jean Baptiste Truteau and Antoine Simon Lecuyer de la Jonchšre did not even make it as far north as the Mandan villages in central North Dakota.[92]

The most significant expedition, however, was the MacKay and Evans Expedition of 1795–1797. James MacKay and John Evans were hired by the Spanish to find a route to the Pacific Ocean and to tell the British to leave the upper Missouri.[93] MacKay and Evans established a winter camp about 20 miles (32 km) south of present-day Sioux City, Iowa, on the Nebraska side where they built Fort Charles. Evans went on to the Mandan villages, where he expelled the British traders. While talking to Native Americans they pinpointed the location of the Yellowstone River, which they called "Yellow Rock" or "Roche Jaune" by the French traders. They created a detailed map of the upper Missouri that was used by Lewis and Clark.[92][94]

Lewis and Clark

On October 27, 1795, the United States and Spain signed Pinckney's Treaty, giving American merchants the "right of deposit" in New Orleans, meaning they could use the port to store goods for export. The treaty also recognized American rights to navigate the entire Mississippi River.[95] In 1798, Spain revoked the treaty and on October 1, 1800, the Spanish secretly returned Louisiana to the French under Napoleon in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. The transfer was so secret that the Spanish continued to administer the territory. In 1801, they restored the United States rights to use the river and New Orleans.[96]

Map of western North America drawn by Lewis and Clark

Map of western North America drawn by Lewis and Clark

President Thomas Jefferson, fearing the cutoffs could occur again, sought to negotiate with France to buy New Orleans for $10 million. Napoleon countered with an offer of $15 million for all of the Louisiana Territory including the Missouri River. The deal was signed on May 2, 1803.[97] On June 20, 1803, Thomas Jefferson instructed Meriwether Lewis[98] to explore the Missouri and look for a water route to the Pacific. Although the deal was signed, Spain still balked at an American takeover, citing that France had never formally taken over the Louisiana Territory. Spain was to formally tell Lewis not to take the journey and expressly forbade Lewis from seeing the McKay and Evans map which was the most detailed and accurate of its time. Lewis gained access to it surreptitiously. To avoid jurisdictional issues with Spain they wintered in 1803–1804 at Camp Dubois on the Illinois (United States) side of the Mississippi.[99][100][101]

Merriweather Lewis and William Clark began their expedition on May 18, 1804, traveling up the Missouri River with a party of thirty-three people in three boats.[101] They spent the following winter on the river in North Dakota and followed the Missouri all the way to its headwaters, upon where they crossed the Rocky Mountains and traveled to the Pacific Ocean.[102] Their travels produced some of the first accurate maps of the northwestern United States and the Pacific Northwest, providing a foundation for future explorers and emigrants. They also negotiated relations with multiple Native American tribes and wrote extensive reports on the climate, ecology and geology of the region. Many present-day geographic names in the region originated from their expedition.[103]

American Frontier

Fur trade

Fur Traders on Missouri River, painted by George Caleb Bingham c. 1845

Fur Traders on Missouri River, painted by George Caleb Bingham c. 1845

As early as the 18th century, fur trappers entered the extreme northern basin of the Missouri River in the hopes of finding populations of beaver and otter, the sale of whose pelts drove the thriving North American fur trade. They came from many different places – some from the Canadian fur corporations at Hudson Bay, some from the Pacific Northwest (see also Maritime Fur Trade), and some from the midwestern United States. Most did not stay in the area for long, as they failed to find significant resources.[104]

The first glowing reports of country rich with thousands of game animals came in 1806 when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark returned from their two-year expedition. Their journals described lands rich with thousands of buffalo, beaver, and river otter; and also an abundant population of sea otters on the Pacific Northwest coast. In 1807, explorer Manuel Lisa organized an expedition which would lead to the explosive growth of the fur trade in the upper Missouri River country. Lisa and his crew traveled up the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, trading manufactured items in return for furs from local Native American tribes, and established a fort at the confluence of the Yellowstone and a tributary, the Bighorn, in southern Montana. Although the business started small, its potential quickly grew it into a thriving trade.[105][106]

Lisa's men started construction of Fort Raymond, which sat on a bluff overlooking the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn, in the fall of 1807. The fort would serve primarily as a trading post for bartering with the Native Americans for furs.[107] This method was unlike that of the Pacific Northwest fur trade, which involved trappers hired by the various fur enterprises, namely Hudson's Bay. Fort Raymond was later replaced by Fort Lisa at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone in North Dakota; a second fort also called Fort Lisa was built downstream on the Missouri River in Nebraska. In 1809 the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company was founded by Lisa in conjunction with William Clark and Pierre Choteau, among others.[108][109]

Fur trapping activities in the early 19th century encompassed nearly all of the Rocky Mountains on both the eastern and western slopes. Trappers of the Hudson's Bay Company, St. Louis Missouri Fur Company, American Fur Company, Rocky Mountain Fur Company, North West Company and other outfits worked thousands of streams in the Missouri watershed as well as the neighboring Columbia, Colorado, Arkansas, Saskatchewan and other river basins. During this period, the trappers, also called mountain men, blazed trails through the wilderness that would later form the paths pioneers and settlers would travel by into the West. Transport of the thousands of beaver pelts required ships, providing one of the first large motives for river transport on the Missouri to start.[110][111]

As the 1830s drew to a close, the fur industry slowly began to die as silk replaced beaver fur as a desirable clothing item – by then, the beaver population of Rocky Mountains streams had been almost entirely decimated by intense hunting. Furthermore, frequent Native American attacks on trading posts made it dangerous for employees of the fur companies. In some regions, the industry continued well into the 1840s, but in others such as the Platte River valley, non-ideal conditions contributed to an earlier demise.[112] The fur trade finally disappeared in the Great Plains around 1850, with the primary center of industry shifting to the Mississippi Valley and central Canada. Despite the demise of the once-thriving industry, however, its legacy led to the opening of the American West and a flood of settlers, farmers, ranchers, adventurers, hopefuls, financially bereft, and entrepreneurs took their place.[111][113]

Settlers and pioneers

The river roughly defined the American frontier in the 19th century, particularly downstream from Kansas City, Missouri, where it takes a sharp eastern turn into the heart of the state of Missouri. All of the major trails for the opening of the American West have their starting points on the river, including the California, Mormon, Oregon, and Santa Fe trails. The first westward leg of the Pony Express was a ferry across the Missouri at St. Joseph, Missouri. Similarly, most emigrants arrived at the eastern terminus of the First Transcontinental Railroad via a ferry ride across the Missouri between Council Bluffs, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska.[114][115] True to the then-ideal of Manifest Destiny, over 500,000 people set out from the river town of Independence to their various destinations in the American West from the 1830s to the 1860s. These people had many reasons to embark on this strenuous year-long journey – economic crisis, and later gold strikes including the California Gold Rush, for example.[116]

Karl Bodmer, Fort Pierre and the Adjacent Prairie, c. 1833

Karl Bodmer, Fort Pierre and the Adjacent Prairie, c. 1833

For most, the route took them up the Missouri to Omaha, Nebraska, where they would set out along the Platte River, which flows from the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and Colorado eastwards through the Great Plains. An early expedition led by Robert Stuart from 1812 to 1813 proved the Platte impossible to navigate by the dugout canoes they used, let alone the large sidewheelers and sternwheelers that would later ply the Missouri in increasing numbers. One explorer remarked that the Platte was "too thick to drink, too thin to plow".[117] Nevertheless, the Platte provided an abundant and reliable source of water for the pioneers as they headed west in covered wagons.[118]

During the 1860s, gold strikes in Montana, Colorado, Wyoming and northern Utah attracted another wave of hopefuls to the region. Although some freight was hauled overland, most transport to and from the gold fields was done through the Missouri River and its tributary the Kansas River, as well as the Snake River in western Wyoming and the Bear River in Utah, Idaho and Wyoming.[119] It is estimated that of the passengers and freight hauled from the Midwest to Montana, over 80 percent were transported by boat, a journey that took 150 days in the upstream direction. A route more directly west into Colorado lay along the Kansas River and the Republican River as well as pair of smaller Colorado streams, Big Sandy Creek and the South Platte River, to near Denver. The gold rushes precipitated the decline of the Bozeman Trail as a popular emigration route, as it passed through land held by often-hostile Native Americans. Safer paths were blazed to the Great Salt Lake near Corinne, Utah during the gold rush period, which led to the large-scale settlement of the Rocky Mountains region and eastern Great Basin.[120]

As settlers expanded their holdings into the Great Plains they naturally ran into conflicts with Native American tribes over land. This resulted in frequent raids, massacres and armed conflicts, leading to the federal government creating multiple treaties with the Plains tribes, which generally involved establishing borders and reserving lands for the indigenous. As with the majority of other U.S.-Native American treaties, these promises were soon broken, leading to huge wars. Over 1,000 battles, big and small, were fought between the U.S. military and Native Americans before the tribes were forced out of their land onto reservations.[121] Conflicts between natives and settlers over the opening of the Bozeman Trail in the Dakotas, Wyoming and Montana led to Red Cloud's War, in which the Lakota and Cheyenne fought against the U.S. Army. The fighting resulted in a complete Native American victory.[122] In 1868, the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed, which "guaranteed" the use of the Black Hills, Powder River Country and other regions surrounding the northern Missouri River to Native Americans without white intervention.[123] Another significant military engagement on the Missouri River during this period was the 1861 Battle of Boonville, which did not affect Native Americans but rather was a turning point in the American Civil War that allowed the Union to seize control of transport on the river, discouraging the state of Missouri from joining the Confederacy.[124]

However, the peace and freedom of the Native Americans did not last for long. The Great Sioux War of 1876-77 was sparked when American miners discovered gold in the Black Hills of western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. These lands were originally set aside for Native American use by the Treaty of Fort Laramie.[123] When the settlers intruded onto the lands, they were attacked by Native Americans. U.S. troops were sent to the area to protect the miners, and drive out the natives from the new settlements. During this bloody period, both the Native Americans and the U.S. military won victories in major battles, resulting in the loss of nearly a thousand lives. The war eventually ended in a U.S. victory; Native Americans were relocated to reservations in Wyoming and Montana, and the Black Hills were given to the settlers.[125]

The Hannibal Bridge was the first bridge to cross the river when it opened in Kansas City in 1869 and traffic on the bridge was a major reason why Kansas City became the largest city on the river upstream from its mouth at St. Louis.[126] Extensive use of paddle steamers on the upper river helped facilitate European settlement of the Dakotas and Montana. The Department of the Missouri, which was headquartered on the banks of the river at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, was the military command center for the Indian Wars in the region.[127] The northernmost navigable point on the Missouri before extensive navigation improvements was Fort Benton, at approximately 2,620 feet (800 m),[128] which lay at the confluence of the Missouri and Marias rivers and was the destination of many pioneers heading into western Montana.[129]

Dams and engineering

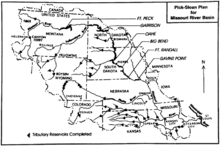

In the 20th century a great number of dams were built along the Missouri River, transforming parts of its course into one of the largest reservoir systems of North America.[9] The Missouri's heavy sediment loads resulted in consistent course changes; its banks originally could shift a half-mile in an year, destroying property and infrastructure. Furthermore, the silt reduced the depth of its channel, exacerbating the power of floods and hindering navigation.[4] As early as the 1860s, plans were already being considered for major alterations in the Missouri basin, and the first dams were built in the 1890s to generate electricity. The 1940s saw two grand proposals put forward for hydrologic modifications on the Missouri: the Pick-Sloan Plan, and the Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project. The USACE took the job of implementing these plans, which called for the construction of levees, the excavation of new channels, and the creation of six major dams that transformed 35 percent of the river's course into a chain of reservoirs. A total of fifteen dams, large and small, now impound long reaches of the Missouri River from south of Helena, Montana to Yankton, South Dakota.[4]

Violent floods struck the Missouri basin in 1844, 1881, 1903, 1908, 1915, 1926–1927 and 1934.[130] In the 1930s, the central United States suffered a devastating drought that led to the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma, Kansas and the surrounding states. Then in 1943, severe flooding wreaked havoc in the watershed of the Missouri and set new records for flood levels in rivers across the central US. This flood caused $1.4 million (about $17.85 million in 2011 dollars) of damage in Omaha when the river breached a levee, destroying over 100 buildings and killing one person.[131] It resulted in great economic loss because of the destruction of millions of acres of farmland, and hampered U.S. military efforts as World War II was then in progress and many war supplies were being manufactured in Omaha, Kansas City and other major cities along the Missouri.[130] Floods and droughts have also caused problems for barge traffic along the Missouri; the river's shallowness, shifting channel and large amounts of underwater and floating debris tended to ground and sink boats.[130][132]

"[The Missouri's temperament was] uncertain as the actions of a jury or the state of a woman's mind."

–Sioux City Register, March 28, 1868[133]From the first decade of the 20th century to the 1940s, a series of dams was built on the Missouri in the vicinity of Great Falls, Montana, to generate power from the Great Falls of the Missouri, a series of five giant waterfalls formed by the river in its path through western Montana. Black Eagle Dam, built in 1891 on Black Eagle Falls, was one of the earliest dams built on the Missouri and the first built in this area.[134] The structure was little more than a weir a few feet high atop Black Eagle Falls, diverting part of the Missouri's flow into the Black Eagle power plant. The main and present structure of the Black Eagle Dam, built in 1926, supplemented power to the hydroelectric plant, which was replaced in that year with a more modern unit.[135] The largest, Ryan Dam, was built in 1913, directly on top of the Grand Falls, the largest waterfall of the Missouri at 87 feet (27 m) high.[136]

In that same time period, the Montana Power Company and several other smaller enterprises began a series of hydroelectric projects on the upper Missouri River, above Great Falls and below Helena, Montana. A small run-of-the river structure at the present site of Canyon Ferry Dam that was completed in 1898 became the second dam to be built on the Missouri; it generated seven and a half megawatts of electricity for Helena and the surrounding countryside.[137] Another dam, the nearby steel Hauser Dam, was built from 1905 to 1907, but failed in 1908 because of structural deficiencies and heavy river flows, causing catastrophic flooding all the way downstream past Craig, Montana. At Great Falls, the Black Eagle Dam was dynamited in order to save a nearby smelter from inundation.[138] Despite the disaster, the dam was rebuilt in 1910 by Montana Power Company using concrete, and stands to this day.[139][140] Holter Dam was the third dam built on this stretch of the Missouri River, about 45 miles (72 km) downstream of Helena. It was begun in 1909 by the Montana Power Company and the United Missouri River Power Company; construction finished in 1918. Its primary purpose was to generate about 48 megawatts of hydroelectricity.[141] Construction of the present, much larger Canyon Ferry Dam by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) did not begin until 1949, and was completed in 1954.[142]

Begun in 1944, the Pick-Sloan Plan called for a series of five reservoirs to be built along the main stem of the Missouri River and many more on its tributaries. Although originally separated into two distinct plans – the Sloan plan, which emphasized irrigation, and Pick plan, which called for flood control, navigation and hydroelectricity generation – the two were combined into one, which eventually totaled 90 major dams. All five were built; today the Missouri flows through Fort Peck, Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall and Gavins Point dams. The Fort Peck, Garrison and Oahe dams are among the largest dams in the world by volume; their sprawling reservoirs also rank within the biggest of the nation.[143] The blueprints also included scores of dams on tributaries, such as the Yellowstone, the Bighorn, the Platte and the Kansas. While passing through government approval several major portions of the plan were canceled, including the construction of dams on the Yellowstone (this river is now the longest free-flowing river in the continental United States).[144][145]

For a while, debate continued whether to build a low run-of-the-river dam at the Garrison Dam site, which would form Lake Sakakawea, or up to 27 on the Yellowstone and its tributaries.[144] Eventually, it was decided to go with the former site, but with the construction of a much larger dam, because of its larger storage capacity and greater hydroelectric potential. This proposal was made by the USBR; however, the agency was not altogether heavily involved in the project. The Flood Control Act of 1944 (Pick-Sloan Legislation) was passed, clearing the way for the Pick-Sloan plan to begin.[146] In the 1950s, construction commenced on the dams that would form the backbone of the plan. Eventually, the project was able to provide water to 4,760,000 acres (19,300 km2) of irrigated farmland and generated power from 17 hydroelectric plants.[144]

A comprehensive list is given below of all fifteen dams on the Missouri River, ordered downstream.[9] Many of the run-of-the-river dams on the Missouri form very small impoundments which may or may not have been given names; those unnamed will be left blank. Most of the dams are on the upper half of the river, otherwise they would impede navigation if built on the lower part of the Missouri.[147]

Key Pick-Sloan dam  Run of the river dam

Run of the river dam Fort Peck Dam, the uppermost of the Pick-Sloan dams

Fort Peck Dam, the uppermost of the Pick-Sloan dams

Dam Height State(s) Megawatts Reservoir Capacity

(KAF)[n 5]Toston[148] 56 ft (17 m) MT 10

3 Canyon Ferry[142] 225 ft (69 m) MT 50 Canyon Ferry Lake 1,973 Hauser[139] 80 ft (24 m) MT 19 Hauser Lake 98 Holter[149] 124 ft (38 m) MT 48 Holter Lake 243 Black Eagle[150] 13 ft (4.0 m) MT 21

Long Pool[n 6] 2 Rainbow[151] 29 ft (8.8 m) MT 36

1 Cochrane[152] 59 ft (18 m) MT 64

3 Ryan[153] 61 ft (19 m) MT 60

5 Morony[154] 59 ft (18 m) MT 48

3 Fort Peck[155] 250 ft (76 m) MT 185 Fort Peck Lake 18,690 Garrison[156] 210 ft (64 m) ND 515 Lake Sakakawea 23,800 Oahe[157] 245 ft (75 m) SD 786 Lake Oahe 23,500 Big Bend[158] 95 ft (29 m) SD 493 Lake Sharpe 1,910 Fort Randall[159] 165 ft (50 m) SD 320 Lake Francis Case 5,700 Gavins Point[160] 74 ft (23 m) NE/SD 132 Lewis and Clark Lake 492 Total 2,787 76,436 "[Missouri River shipping] never achieved its expectations. Even under the very best of circumstances, it was never a huge industry."

~Richard Opper, former Missouri River Basin Association executive director[161]Boat travel on the Missouri first started with the wood-framed bull boats and canoes of the Native Americans, which were used for thousands of years before the introduction of larger craft to the river upon colonization of the Great Plains. The first steamboat on the Missouri was the Independence, which started running between St. Louis and Keytesville around 1819.[162] By the 1830s, large mail and freight-carrying vessels began operating on the river between Kansas City and St. Louis, and some even further up. A handful, such as the Western Engineer and the Yellowstone, were able to make it up the river as far as eastern Montana. At this time, the North American fur trade was at its height, and more and more ships began traveling nearly the whole length of the Missouri from Montana's rugged Missouri Breaks to the mouth, carrying beaver and buffalo furs to and from the areas that the trappers frequented.[163]

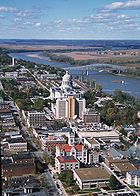

Left: Aerial view of the Missouri River winding through Omaha, Nebraska; Right: Painting of the steamboat Yellowstone, one of the earliest commercial vessels to run on the river, circa 1833. The dangerous currents in the river caused the ship to run aground on a sandbar in this illustration.Water transport increased through the 1850s with multiple craft ferrying pioneers, emigrants and miners; many of these runs were from St. Louis or Independence to near Omaha. There, most of these people would set out overland along the broad, swift but shallow and unnavigable Platte River, which was described by pioneers as "a mile wide and an inch deep" and "the most magnificent and useless of rivers".[164] By 1858, there were over 130 boats operating full-time on the Missouri, with many more smaller vessels. The industry's success, however, did not guarantee safety. In the early decades before the river's flow was controlled by man, its sketchy rises and falls and its massive amounts of sediment, which prevented a clear view of the bottom, wrecked some 300 boats.[165] Because of the danger of navigating the Missouri River, the average ship's lifespan was short – about four years – before she was sunk or pulled out of service. Eventually, the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad ended steamboat commerce on the Missouri. The number of boats slowly dwindled, until there was almost nothing left by the mid-1880s.[166][167]

Passage to Sioux City

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Missouri River has been extensively engineered for water transport purposes. In 1912, the USACE was authorized to maintain the Missouri to a depth of six feet (1.8 m) from Kansas City, Missouri to the mouth, a distance of 553 miles (890 km). This was accomplished by constructing levees and wing dams to direct the river’s flow into a narrower, straighter channel and prevent sedimentation. In 1925, the USACE began a project to widen the navigation channel (the portion of the river's breadth maintained to a certain depth for the passage of large vessels) to 200 feet (61 m). Then, in 1927, the USACE started the dredging of a deep-water channel from Kansas City to Sioux City, Iowa. Channeling has reduced the river's length from 2,540 miles (4,090 km) in the late 19th century to 2,341 miles (3,767 km) in the present day.[3][168]

Gavins Point Dam at Yankton, South Dakota is the uppermost obstacle to navigation from the mouth on the Missouri today.

Gavins Point Dam at Yankton, South Dakota is the uppermost obstacle to navigation from the mouth on the Missouri today.

All these revetments, however, did not allow for the passage of large riverboats and barges. Construction of dams on the Missouri under the Pick-Sloan Plan in the 1950s aided navigation by regulating water flow. The six large reservoirs along the Missouri – Fort Peck, Sakakawea, Oahe, Francis Case, Sharpe, and Lewis and Clark – can hold a combined 74,102,000 acre feet (91.403 km3) of water, more than one year's worth of the river's flow.[169]

In 1945, the USACE began the Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project, which would permanently increase the river’s navigation channel to a width of 300 feet (91 m) and a depth of nine feet (2.7 m). During work that continues to this day, the 735-mile (1,183 km) navigation channel from Sioux City to St. Louis has been controlled by building rock dikes to direct the river’s flow and scour out sediments, sealing and cutting off meanders and side channels, and dredging the riverbed.[170] However, the naturally fast and shallow Missouri has at times resisted the efforts of the USACE to control its depth. In 2006, several U.S. Coast Guard work boats ran aground in the Missouri River because the navigation channel had been severely silted.[171] The USACE was blamed for failing to maintain the channel to the minimum depth.[172]

The Missouri River near New Haven, Missouri, looking upstream – note the riprap wing dam protruding into the river from the left to direct its flow into a narrower channel

The Missouri River near New Haven, Missouri, looking upstream – note the riprap wing dam protruding into the river from the left to direct its flow into a narrower channel

In 1929, the Missouri River Navigation Commission estimated the total amount of goods shipped on the river annually at 15 million tons (13.6 million metric tons), providing widespread consensus for the creation of a navigation channel. However, shipping traffic has since been far lower than expected – shipments of commodities including produce, manufactured items, lumber, and oil averaged only 8.2 million tons (7.4 million metric tons) per year from 1994 to 2006.[173] Of the tonnage of materials shipped, Missouri is by far the largest user of the river accounting for 83 percent of river traffic – while Kansas has 12 percent, Nebraska three percent and Iowa two percent. Almost all of the barge traffic on the Missouri River ships sand and gravel dredged from the lower 500 miles (800 km) of the river; the remaining portion of the shipping channel now sees little to no use by commercial vessels.[173]

Traffic decline

Tonnage of goods shipped by barges has seen a serious decline from the 1960s to the present on the Missouri River. In the 1960s, the USACE predicted an increase to 12 million annual tons (10.8 million metric tons) by 2000, but instead the opposite has happened. Tonnage of barge-shipped goods dropped from 3.3 million tons (3 million metric tons) in 1977 to just 1.3 million tons (1.18 million metric tons) in 2000.[174] One of the largest drops has been in agricultural products, especially wheat. Part of the reason is that irrigated land along the Missouri has only been developed to a tenth of its potential. In 2006, barges on the Missouri hauled only 200,000 tons (181,437 metric tons) of products which is equal to the amount of daily freight traffic on the Mississippi.[175]

Droughts and the development of other transportation systems have hampered river traffic on the Missouri in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. As shipping turns to other forms of transportation such as trucks and trains, annual boat traffic has dropped to 245,000 tons (222,260 metric tons) as of 2009, which is also "the first year of recovery after eight years of drought".[161] Also, the failure of the USACE to consistently maintain the navigation channel has negatively impacted the industry. Currently, efforts are being made to revive the shipping industry on the Missouri River, because of the efficiency and cheapness of river transport to haul agricultural products, and the overcrowding of alternative transportation routes. Solutions such as expanding the navigation channel and releasing more water from reservoirs during the peak of the navigation season are being considered.[176][177]

Ecology and human impact

Ecoregions of the Missouri basin as defined by the World Wildlife Fund and Nature Conservancy

Ecoregions of the Missouri basin as defined by the World Wildlife Fund and Nature Conservancy

Historically, the Missouri's floodplain, an area thousands of square miles in size, supported a wide diversity of plant and animal species, generally increasing in size and variety as one proceeded downstream from the cold, relatively arid headwaters in Montana to the temperate, moist climate of Missouri. The river's riparian zone consisted primarily of cottonwoods, willows and sycamores, with several other types of trees such as maple and ash. The height of the trees generally increase farther from the riverbanks for a limited distance, as the roots of the trees closer to the river are vulnerable to soil erosion during floods. Because of its large sediment concentrations, the Missouri does not support many aquatic invertebrates.[178] However, the basin does support 300 species of birds[179] and 150 species of fish.[180] The Missouri also supports several species of mammals in its aquatic and riparian habitats, such as minks, river otters, beavers, muskrats, and raccoons.[133]

The Missouri River basin is divided into three freshwater ecoregions by the World Wide Fund For Nature: the Upper Missouri, Lower Missouri and Central Prairie. The Upper Missouri, encompassing an area roughly within Montana, Wyoming, southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, and North Dakota is defined by a continental climate with dry grasslands and sparse biodiversity because of Ice Age glaciations; there are no known endemic species. Except for the headwaters in the Rockies, there is little precipitation in this part of the watershed.[181] The Middle Missouri ecoregion, extending through Colorado, southwestern Minnesota, northern Kansas, Nebraska, and parts of Wyoming and Iowa, has a temperate climate with moderate amounts of rainfall. Plant life is more diverse in the Middle Missouri but it does not have many species of fish.[182] Finally, the Central Prairie ecoregion is situated on the lower part of the Missouri, encompassing all or parts of Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. This region has the greatest diversity of plants and animals of the three ecoregions, despite its large seasonal temperature fluctuations. There are 13 species of crayfish endemic to the lower Missouri.[183]

The Missouri's confluence with the Nishnabotna River in western Missouri – agricultural fields dominate most of the landscape, which was probably once floodplain.

The Missouri's confluence with the Nishnabotna River in western Missouri – agricultural fields dominate most of the landscape, which was probably once floodplain.

Throughout its history of industrialization and commerce, the Missouri has been severely polluted and degraded by human activities along its shores; in addition, most of the river's floodplain habitat is long gone, replaced by irrigated agricultural land. Additionally, development of the floodplain has led to more and more people and industries within areas at high risk of inundation. Levees have been constructed along much of the river in order to keep floodwaters within the channel, but this also leads to faster stream velocity and thence increasing peak flows in downstream areas. A major problem in the river is the excess of fertilizer runoff and resultantly, elevated levels of nitrogen. A large amount of fertilizer travels down the Missouri from farmland in the states of Iowa and Missouri, but it is not the most affected river in the Mississippi basin – the upper Mississippi, Illinois and Ohio Rivers are even more severely affected. The result of this pollution are algae blooms which result in oxygen depletion, and the vast Gulf of Mexico dead zone at the end of the Mississippi Delta.[184][185]

Environmentalists contend that channelization of the lower Missouri waters, which made the river narrower, deeper, and less accessible to riparian flora and fauna, has caused massive biological loss. The construction of numerous dams and river bank control projects has converted over 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) of Missouri River floodplain to agricultural land, and significantly reduced the volume of sediment transported downstream by the river and eliminating critical habitat for fish and amphibians, and nesting sites for birds.[186] Declines in populations of these species prompted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to issue a biological opinion in 2000 (amended in 2003) recommending restoration of river habitats for federally endangered bird and fish species.

In response, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began constructing restoration projects along the lower Missouri River in the early 2000s. Because of extremely low use of the shipping channel in the lower Missouri maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, it is considered feasible to remove some of the levee, dikes, and wing dams that constrict the river’s flow, to allow it to naturally restore its environment.[186] As of 2001, there were 87,000 acres (350 km2) of riverside floodplain undergoing active restoration.[187]

However, these restoration projects re-mobilized some of the sediments that had been trapped behind bank stabilization structures, prompting concerns that nutrients carried with the re-introduced sediments could exacerbate nutrient and sediment pollution locally and downstream in the northern Gulf of Mexico. A 2010 National Research Council report assessed the roles of sediment in the Missouri River, evaluating current habitat restoration strategies and alternative ways to manage sediment.[188] The report found that a better understanding of sediment processes in the Missouri River, including the creation of a “sediment budget”—an accounting of sediment transport, erosion, and deposition volumes for the length of the Missouri River— would provide a foundation for projects to improve water quality standards and protect endangered species.[189]

Tourism and recreation

Part of the Missouri National Recreational River, a 98-mile (158 km) preserved stretch of the Missouri on the border of South Dakota and Nebraska

Part of the Missouri National Recreational River, a 98-mile (158 km) preserved stretch of the Missouri on the border of South Dakota and Nebraska

The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, some 3,700 miles (6,000 km) long, follows nearly the entire Missouri River from its mouth to its source, retracing the route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Extending from Wood River, Illinois in the east to Astoria, Oregon in the west, it also follows portions of the Mississippi River and Columbia River. The trail, which spans through eleven U.S. states, is maintained by various federal and state government agencies; it passes through some 100 historic sites, notably archaeological locations including the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.[190][191]

Parts of the river itself are also designated for recreational or preservational use. The Missouri National Recreational River consists of portions of the Missouri downstream from Gavins Point Dam and Fort Randall Dam that total 98 miles (158 km).[192][193] These reaches of the river exhibit islands, meanders, sandbars, underwater rocks, riffles, snags, and other once-common features of the lower river that have now disappeared under reservoirs or have been destroyed by channeling.[194]

Downstream from Great Falls, Montana, about 149 miles (240 km) of the river course through a rugged series of canyons and badlands known as the Missouri Breaks. This part of the river, designated a U.S. National Wild and Scenic River in 1976, flows within the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument, a 375,000-acre (1,520 km2) preserve comprising steep cliffs, deep gorges, arid plains, badlands, archaeological sites, and whitewater rapids on the Missouri itself. The preserve also includes a wide variety of plant and animal life; recreational activities include boating, rafting, hiking and wildlife observation.[195][196]

In north-central Montana, approximately 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) along over 125 miles (201 km) of the Missouri River, centering around Fort Peck Lake, comprise the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge.[197] The wildlife refuge consists of a native northern Great Plains ecosystem that has not been heavily affected by human development, except for the construction of Fort Peck Dam. Although there are few designated trails, all the land within the preserve is open to hiking and camping.[198]

Many U.S. national parks, such as Glacier National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, Yellowstone National Park and Badlands National Park are in the watershed. Parts of other rivers in the basin are also set aside for preservation and recreational use – notably the Niobrara National Scenic River, which is a 76-mile (122 km) protected stretch of the Niobrara River, one of the Missouri's longest tributaries.[199] National Historic Landmarks on the river include Three Forks of the Missouri,[200] Fort Benton, Montana,[201] Big Hidatsa Village Site,[202] Fort Atkinson, Nebraska[203] and Arrow Rock Historic District.[204]

The Missouri River in Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument, Montana, at the confluence with Cow Creek See also

- Across the Wide Missouri

- Great bison belt

- List of longest main-stem rivers in the United States

- List of crossings of the Missouri River

- List of settlements along the Missouri River

- Montana Stream Access Law

- Montana Wilderness Association

- Sacagawea

Notes

- ^ The Missouri's flow at Culbertson, Montana, 25 mi (40 km) above the confluence of the two rivers, is about 9,820 cu ft/s (278 m3/s)[10] and the Yellowstone's discharge at Sidney, Montana, roughly the same distance upstream along that river, is about 12,370 cu ft/s (350 m3/s).[11]

- ^ Length includes the 990-mile (1,590 km) figure from the USGS (obtained by combining the main stem and North Platte), plus the length of Big Grizzly Creek, which extends another 35 miles (56 km).[8]

- ^ Length includes those of the Republican and Arikaree rivers, to the farthest headwaters

- ^ Length includes the longest headwaters fork, the Marais des Cygnes River

- ^ KAF = 1,000 acre feet (1,200,000 m3)

- ^ Name used by area residents to refer to the smooth, almost lake-like 55 mi (89 km) stretch of the Missouri between the Black Eagle Dam and the town of Cascade. Only about 2 mi (3.2 km) of the so called "Long Pool" are actually part of the impoundment behind the dam.

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Missouri River". Geographic Names Information System, U.S. Geological Survey. 1980-10-24. http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/f?p=gnispq:3:::NO::P3_FID:756398. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ "Firehole River". Geographic Names Information System, U.S. Geological Survey. 1979-06-05. http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/f?p=gnispq:3:::NO::P3_FID:1588484. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ^ a b "Missouri River Environmental Assessment Program Summary". U.S. Geological Survey. http://infolink.cr.usgs.gov/Science/MoREAP/moreap_brief.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Missouri River Story". Columbia Environmental Research Center. United States Geological Survey. http://infolink.cr.usgs.gov/The_River/MORstory.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ a b c d e f "USGS Gage #06934500 on the Missouri River at Hermann, Missouri: Water-Data Report 2009". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 2009. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06934500.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Pinter, Reuben A.. "Hydrologic History of the Lower Missouri River". Geology Department. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. http://www.grha.net/site/programs/river-study/. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ a b c d United States Geological Survey. "United States Geological Survey Topographic Maps". TopoQuest. http://www.topoquest.com/map.php. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ACME Mapper. USGS Topo Maps for United States (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. http://mapper.acme.com/. Retrieved 2010-5-08.

- ^ a b c "Interactive Maps and Air photos for Missouri River Dams and Reservoirs". Mapping Support. http://www.mappingsupport.com/p/gmap4.php?q=https://sites.google.com/site/gmap4files/p/news/missouri_river.txt&label=on.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06185500 on the Missouri River near Culbertson, MT". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1941-present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06185500.2010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06329000 on the Yellowstone River near Sidney, MT". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1911-present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06329500.2010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ Athearn, p. 89

- ^ "Missouri River". Columbia Environmental Research Center. United States Geological Survey. 2009-09-08. http://www.cerc.usgs.gov/ScienceTopics.aspx?ScienceTopicId=10. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ "North America". Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/418612/North-America. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ "USGS Gage #07010000 on the Mississippi River at St. Louis, Missouri: Water-Data Report 2009". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 2009. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/07010000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-24. Note: This gauge is just below the Missouri confluence, so the Missouri discharge was subtracted from 190,000 cubic feet per second (5,400 m3/s) to get this amount.

- ^ a b "Yellowstone River at Sidney, Montana". River Discharge Database. Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment. 1965-1984. http://www.sage.wisc.edu/riverdata/scripts/station_table.php?qual=32&filenum=2845. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ a b "USGS Gage #06805500 on the Platte River at Louisville, NE". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1953–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06805500.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". Eastern Geographic Science Center. U.S. Geological Survey. 2005-04-29. http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html#14,000. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ a b "Watersheds (map)". Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-02-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20080227060842/http://www.cec.org/naatlas/img/NA-Watersheds.gif. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "Great Divide Basin". Wyoming State Geological Survey. http://www.wsgs.uwyo.edu/StratWeb/GreatDivideBasin/Default.aspx. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ^ Stone, Clifton. "Missouri River". The Natural Source. Northern State University. http://www3.northern.edu/natsource/HABITATS/Missio1.htm. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ^ McFarlan and McWhirter, p. 32

- ^ a b Kammerer, J.C. (May 1990). "Largest Rivers in the United States". U.S. Geological Survey. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1987/ofr87-242/. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Boundary Descriptions and Names of Regions, Subregions, Accounting Units and Cataloging Units". U.S. Geological Survey. http://water.usgs.gov/GIS/huc_name.html. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The National Map". U.S. Geological Survey. http://viewer.nationalmap.gov/viewer/. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06892350 on the Kansas River at DeSoto, KS". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1917–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06892350.2010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06174500 on the Milk River at Nashua, MT". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1940–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06174500.2010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06478500 on the James River near Scotland, SD". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1928–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06478500.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ Miller, Kirk A. (1999). "Surface Water". Environmental Setting of the Yellowstone River Basin, Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. U.S. Geological Survey. http://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/wri984269/surwater.html. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ a b "USGS Gage #06452000 on the White River near Oacoma, SD". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1928–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06452000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06337000 on the Little Missouri River near Watford City, ND". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1935–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06337000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06926510 on the Osage River below St. Thomas, MO". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1996–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06926510.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06465500 on the Niobrara River near Verdel, NE". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1928–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06465500.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06439500 on the Cheyenne River at Eagle Butte, SD". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1935–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2008/pdfs/06439500.2008.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ a b Kammerer, J.C. (1990-05). "Largest Rivers in the United States". U.S. Geological Survey. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1987/ofr87-242/. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ "Rivers". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2010-10-25. http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/learningresources/facts/rivers.html. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "USGS Gage #07010000 on the Mississippi River at St. Louis, Missouri: Peak Streamflow". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1844-2009. http://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/peak?site_no=06934500&agency_cd=USGS&format=html. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06934500 on the Missouri River at Hermann, Missouri: Monthly Average Flow". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1957–present. http://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/monthly/?referred_module=sw&site_no=06934500&por_06934500_6=834553,00060,6,1928-10,2010-08&format=html_table&date_format=YYYY-MM-DD&rdb_compression=file&submitted_form=parameter_selection_list. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ^ "Sage Database for Great Falls". Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE), Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison. http://www.sage.wisc.edu/riverdata/scripts/station_table.php?qual=32&filenum=1454.

- ^ "Oahe Dam discharge rate". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, District, Missouri River Region. http://www.nwd-mr.usace.army.mil/rcc/reports/showrep.cgi?4BULL0MR1.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06486000 on the Missouri River at Sioux City, IA". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1953–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06486000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06610000 on the Missouri River at Omaha, NE". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1953–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06610000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06893000 on the Missouri River at Kansas City, MO". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1958–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06893000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ "USGS Gage #06909000 on the Missouri River at Boonville, MO". National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1958–present. http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2009/pdfs/06909000.2009.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ Jones, Craig H.. "Photo map of the western U.S.: Cenozoic". Western US Tectonics. University of Colorado. http://www.colorado.edu/GeolSci/Resources/WUSTectonics/PhotoMap.html. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Cretaceous Paleogeography, Southwestern US". Northern Arizona University. http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~rcb7/crepaleo.html. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ Nicholls, Anthony P. (1989-09-18). "Paleobiogeography of the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway: the vertebrate evidence". Department of Biological Sciences (University of Calgary).

- ^ King, P. B., pp. 27–28

- ^ King, P. B., pp. 130–131

- ^ Baldridge, pp. 190–204

- ^ Roberts and Hodsdon, pp. 113–116

- ^ Benke and Cushing, p. 434

- ^ a b c Chapin, Charles E. (2008). "Interplay of oceanographic and paleoclimate events with tectonism during middle to late Miocene sedimentation across the southwestern USA". Geosphere 4 (6): 976. doi:10.1130/GES00171.1.