- Liberation (film series)

-

Liberation

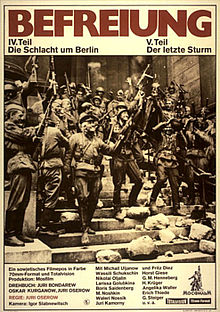

A 1970 poster of Liberation.Directed by Yuri Ozerov

co-director: Julius KunProduced by Lidia Kanareikina

co-producers: Kurt Lichterfeld, Wilhelm Hollender, Jerzy Rutowicz.Written by Yuri Bondarev, Oscar Kurganov Screenplay by Yuri Ozerov, Yuri Bondarev, Oscar Kurganov Narrated by Artyom Karapetian Starring Nikolay Olyalin, Larisa Golubkina, Boris Seidenberg Music by Yuri Levitin (composer), Aram Khachaturian (conductor) Cinematography Igor Slabnevich Editing by Ekaterina Karpova Studio Mosfilm

DEFA-Babelsberg

ZF-Start (films I, II)

PRF-ZF (III-V)

Avala Film (I)

Dino de Laurentiis CinematograficaRelease date(s) I, II: 7 May 1970

III: 31 July 1971

IV, V : 5 November 1971Running time 477 minutes (original)

445 minutes (remastered 2002 version)

Part I: 88 minutes

Part II: 85 minutes

Part III (1): 58 minutes

Part III (2): 64 minutes

Part IV: 79 minutes

Part V: 71 minutesCountry Soviet Union

East Germany

Poland

Yugoslavia

ItalyLanguage Russian, German, English, Polish, Italian, French, Serbo-Croatian Budget $40,000,000.[1] Liberation (Russian: Освобождение, translit. Osvobozhdenie, German: Befreiung, Polish: Wyzwolenie) is an epic five-part film series considered the most large-scale World War II film ever made in the Soviet Union. Filmed from 1967 to 1971, the first part was released during 1970 for the 25th anniversary of Victory Day. The series was a Soviet-Polish-East German-Italian-Yugoslavian co-production, by the studios Mosfilm, ZF-Start/PRF-ZF, Deutsche Film AG, Dino de Laurentiis Cinematografica and Avala Film. It was directed by Yuri Ozerov. The script was written by Yuri Bondarev and Oscar Kurganov.

The films are a dramatized account of the liberation of the Soviet Union's territory and the subsequent defeat of Nazi Germany in the Great Patriotic War, focusing on five major Eastern Front campaigns: the Battle of Kursk, the Lower Dnieper Offensive, Operation Bagration, the Vistula-Oder Offensive and the Battle of Berlin.

The series was created under the aegis of Soviet authorities, with the military and political establishment heavily involved in the production. Liberation was intended to present a heroic depiction of the Soviet role in the Second World War. Although many critics described it as an unrealistic glorification of the past, it became one the most widely recognized Soviet films dealing with the subject.

Contents

Plot

Film I: The Fire Bulge

Both the Germans and the Soviets prepare for the anticipated Battle of Kursk. On 5 July, Soviet troops capture a German sapper who reveals that an all-out offensive would commence on 0300. General Konstantin Rokossovsky orders General Vasily Kazakov to launch a preemptive artillery strike. At 0310, Captain Tzvetaev, an anti-tank gun battery commander, observes his quiet sector along with Major Orlov and Major Maximov. Their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Lukin, tells them to prepare for the upcoming assault.

General Nikolai Vatutin puts General Mikhail Katukov's force on combat alert. Sergeant Dorozhkin hastens to wake up his commander, Lieutenant Vasiliev. Soon after, the Germans finally attack. In the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, General Andrei Vlasov addresses the Soviet prisoners of war, exhorting them to join the Russian Liberation Army. Yakov Dzhugashvili refuses to write to his father when Vlasov offers to exchange him for Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus.

The German tanks advance, overwhelming the Soviet defenses. Many soldiers panic. Maximov flees, but turns back when he is accused of cowardice. After being knocked unconscious, he is captured. The visiting Walter Model sets him free so he could tell of the inevitable German victory. Shocked, Maximov taunts his interrogator, who shoots him.

When General Aleksei Antonov informs Stalin about the German proposal regarding Yakov, he rejects it, saying he will not trade a Field Marshal for a soldier. In Yugoslavia, Tito's partisans break out of an encirclement.

On 11 July the Soviet counter-offensive is launched. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein commits all his forces to a final assault. Vasileev's crew are drawn into a combat between German and Soviet tank crewmen who abandoned their burning vehicles.

Vatutin begs Vasilevsky to call Stalin and convince him to send in the reserve. The 5th Tank Army and the 5th Guards Army counter-attack, repelling the Germans. The commander of the 19th Panzer Division commits suicide after failing to defeat the Soviets. The Red Army is victorious.

Film II: Breakthrough

After the Allied landing in Sicily, Mussolini is arrested on the King's orders. In Warsaw, The Polish Resistance bombs a German cinema. After Mussolini is rescued, Hitler tells him that the Soviets will never breach the Dnieper line.

The Red Army reaches the river. Lukin's regiment crosses it, presumably as the division's vanguard. Lukin's commander, Gromov, is told that his soldiers on the other bank are merely a ploy to mislead the enemy, and the main crossing would take place elsewhere. The regiment is cut off without reinforcements and wiped out in the fighting against the Germans and the RLA. Lukin is killed. Tzvetaev leads the surviving soldiers back to their lines.

In Moscow, Stalin orders Antonov to capture Kiev until 6 November, the eve to the anniversary of the October Revolution. General Rybalko stealthily redeploys his Tank Army to support the operation. When Zhukov doubts General Kiril Moskalenko's plan to take the city, General Yepishev assures him it would work. After a fierce fight, Kiev is liberated. In Tehran, the Allied leaders meet to discuss the future of the war.

Film III: Direction of the Main Blow

Part 1

In Tehran, Stalin declares that a Soviet offensive would take place soon after the Normandy landings. At the British embassy in Ankara, the ambassador's butler steals classified documents. In Poland, Vatutin is killed in an ambush. In the Kremlin, the Stavka decides to strike in Belarus.

Meanwhile, Orlov's battalion is engaged in heavy fighting. Zoia insists to evacuate the wounded. To save her from being captured, Orlov leads his soldiers in a charge and takes the enemy-held height.

After concluding that the Belarus marshes are passable, Rokossovsky demands that the main effort will be directed towards Bobruisk and insists on it until Stalin approves. Zhukov suggests sending the four Tank Armies to Ukraine. The German High Command is convinced that the offensive would be in that direction. Panteleimon Ponomarenko orders the Belorussian partisans to attack all railways. Operation Bagration is launched. When his plane crashes, the Normandie-Niemen pilot Jacques is rescued by Soviet pilot Zaitsev. After Zaitsev takes off, they are both shot down by Flak.

Part 2

The Soviets march on Bobruisk, destroying General Hamann's forces. Outside the city, Tzvetaev tells Zoia that in spite of the war, he is happy to have met her. The Belorussian partisans and the Red Army liberate Minsk. 50,000 German prisoners are paraded in Moscow. A group of German officers tries to assassinate Hitler and take power, but fails. Churchill is pleased to hear of this, telling that the resulting peace would have left the Allies in Normandy while Stalin is at the gates of Europe. Hitler appoints Guderian as the new chief of the OKH.

In Poland, Zawadzki and Berling watch the Bug River. Zawadzki says he will never forget the day in which they returned home. Rokossovsky joins them, adding in Polish that he will never forget it either. The Polish 1st Army crosses the river, waved to by the Red Army soldiers.

Film IV: The Battle of Berlin

In late 1944, Stalin orders to hasten the Vistula-Oder offensive in order to relieve the Allies, who are threatened by the Ardennes Offensive. In Poland, Zhukov appoints Orlov to a regiment commander. Karl Wolff is sent to negotiate with the Americans at Geneva.

Zhukov rejects Stavka's order to take Berlin, assessing that the Germans would strike his flank in Pomerania and redeploying his forces accordingly. In Yalta, Stalin notifies Churchill and Roosevelt that he knows of their secret dealings with the enemy. Saying that the mutual trust between them is of the highest value, he tears apart the picture showing Allen Dulles and Wolff.

The German attempt to counter-attack fails. Dorozhkin and the Polish sergeant Pelka liberate a group of concentration camps' prisoners, among them the German communist Wilnie. Zhukov orders to cross the Oder with searchlights directed at the opposite bank, to dazzle the Germans. Hitler appoints Hans Krebs as the new chief of the OKH, instead of Guderian.

The Red Army crosses the Oder and the Neisse rivers, scattering the German defenders and approaching Berlin. General Lelyushenko's soldiers capture a fifteen-year-old Hitlerjugend sniper; the General sends him to his mother.

Vasilev's tank crushes into a house. He and Dorozhkin have a pleasant meal with the German owner and his family while their Kyrgyz driver repairs the vehicle. The Soviets and the Poles storm the Tiergarten, avoiding causing harm to the animals.

Film V: The Last Assault

In Berlin, Lt. Yartsev's men fight their way into a house where they meet Tzvetaev. They are welcomed by the old woman who owns the home. Afterwards, while fighting in the U-Bahn, Tzvetaev captures a German soldier who is certain the Soviets would execute him, but is sent free. Hitler orders to flood the U-Bahn tunnels. Tzvetaev drowns while rescuing civilians.

Colonel Zhenchik, commander of the 150th Rifle Division's 756th Regiment, selects Yegorov and Kantaria to carry the Victory Banner when Captain Neustroev's soldiers would attack the Reichstag. Dorozhkin is assigned to Neustroev's company as a radio operator. In the Führerbunker, after marrying Eva Braun, Hitler murders her and commits suicide. At the Reichstag, Dorozhkin is killed in the fighting. The Victory Banner is unfurled on the dome. On 2 May, after negotiations, the Berlin garrison surrenders unconditionally.

Outside the Reichstag, Vasiliev - who failed to find Dorozhkin - asks the crying Zoia why is she mourning when they have won. Next to them, Orlov, Yartsev and an immense crowd of Red Army soldiers celebrate victory. In the last scene, the question What has Fascism brought to the world? is answered with the death toll of World War II by country. The film ends with a shot of the inscription on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier: Your Name Unknown, Your Deed Immortal.

Cast

Soviet actors

- Nikolay Olyalin as Captain Tzvetaev.

- Larisa Golubkina as nurse Zoia.

- Vsevolod Sanaev as Lieutenant Colonel Lukin.

- Boris Seidenberg as Major Orlov.

- Viktor Avdyushko as Major Maximov.

- Yuri Nazarov as Russian Liberation Army soldier.

- Mikhail Gluzsky as Sergeant Ryazhentzev.

- Ivan Mykolaychuk as Sergeant Savchuk.

- Georgi Burkov as commander of Tzvetaev's adjacent battery.

- Vladimir Kashpur as soldier with wooden footwear.

- Leonid Kuravlyov as signaler sent by Chuikov.

- Bukhuti Zaqariadze as Joseph Stalin.

- Mikhail Ulyanov as Marshal Georgy Zhukov.

- Ivan Pereverzev as General Vasily Chuikov.

- Roman Tkachuk as General Alexei Yepishev.

- Anatoly Borisovich Kuznetsov as General Georgi Zakharov.

- Viktor Bortsov as General Grigory Oriol.

- Yuri Leghkov as Marshal Ivan Konev (films I-II).

- Vasily Shukshin as Marshal Ivan Konev (films III-V).

- Vladimir Samoilov as Colonel Gromov

- Mikhail Nozhkin as Lieutenant Yartsev

- Roman Khomiatov as German interpreter who shot Maximov.

- Yuri Kamorny as Lieutenant Vasiliev.

- Valeri Nosik as Sergeant Dorozhkin.

- Vladimir Samoilov as Colonel Gromov.

- Evgeny Burenkov as Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky.

- Sergei Kharchenko as General Nikolai Vatutin.

- Vladlen Davydov as General Konstantin Rokossovsky.

- Dimitry Franko as General Pavel Rybalko.

- Vladislav Srtzhelchik as General Aleksei Antonov.

- E. Kolchinski as General Ivan Chernyakhovsky.

- Valeri Kern as General Hovhannes Bagramyan.

- Nikolai Rushkovski as General Kiril Moskalenko.

- Vladimir Kosenko as General Kiril Meretskov.

- Konstantin Zabelin as General Mikhail Katukov.

- Vladimir Zamansky as General Pavel Batov.

- Klion Protasov as General Sergei Shtemenko.

- Aleksander Afanasiev as General Dmitry Lelyushenko.

- Grigory Mikhaylov as General Mikhail Malinin.

- Vyacheslav Voronin as General Alexei Burdeinei.

- Anatoly Romashin as General Vasily Shatilov.

- Nikolai Rybnikov as General Mikhail Panov.

- Alex Presnetsov as General Sergei Rudenko.

- Nikolai Lebedev as General Stepan Krasovsky.

- Leonid Dovlatov as General Sergei Galadzhev.

- Peter Glebov as General Pavel Rotmistrov.

- A. Petrov as General Vasily Kazakov.

- Piotr Scherbakov as General Konstantin Telegin.

- Yuri Maximov as General Semion Ivanov.

- Sergei Lyachnitzki as General Semen Bogdanov.

- Alexei Alexeev as General Vasily Kuznetsov.

- Mikhail Postinkov as General Vasily Sokolovsky.

- Lev Polyakov as General Andrei Grechko.

- Vadim Grachev as Colonel Anatoly Golubov.

- O. Olenikov as Captain of the 2nd Rank Stepan Lyalko.

- Viktor Baikov as Vyacheslav Molotov.

- Nikolay Bogolyubov as Marshal Kliment Voroshilov.

- Alexei Glazrin as Panteleimon Ponomarenko.

- A. Bugatkin as Vasily Kozlov.

- Lev Lobov as Colonel Fedor Zinchenko.

- Vladimir Korenev as Captain Stepan Neustroev.

- Eduard Izotov as Lieutenant Alexei Berest

- Genadi Khrashenikov as Mikhail Yegorov.

- Gogi Kharabdze as Meliton Kantaria.

- Yuri Pomernatzev as General Andrei Vlasov.

- Olev Eskola as Arthur von Christmann.

- Heino Mandri as Anton Kaindl.

- Tõnu Aav as Kaindl's deputy.

- Ioseb Gugichaishvili as Yakov Dzhugashvili.

- Yuri Durov as Winston Churchill.

- Evgeni Vlasov as Anthony Eden.

- Aleksander Barushnoi as Field Marshal Alan Brooke.

- Konstantin Tirtov as Harry Hopkins.

- Elizaveta Alexeeva as Eleanor Roosevelt.

- Nikolay Yeryomenko as Marshal Josip Broz Tito.

- Voldemārs Akurāters as Captain William F. Stuart.

- Yulia Dioshi as Magda Goebbels.

- Visarion Dzhakhutashvili as General Vittorio Ambrosio.

- Amiran Dolidze as General Angelo Cerica.

- Yuri Vishinsky as Dr. Nicolò de Cesare.

- Georgi Tusuzov as King Victor Emmanuel III.

East German actors

- Fritz Diez as Adolf Hitler.

- Horst Giese as Bruno Fermella (Part I)/Joseph Goebbels (Part I - voice, Parts IV-V - in person).

- Gerd Michael Henneberg as Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

- Werner Dissel as General Alfred Jodl.

- Siegfried Weiß as Field Marshal Erich von Manstein.

- Peter Sturm as General Walter Model.

- Hannjo Hasse as Field Marshal Günther von Kluge.

- Alfred Struwe as Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg.

- Martha Beschort-Diez as old woman in Berlin.

- Horst Gill as Otto Günsche.

- Angelika Waller as Eva Braun.

- Erich Thiede as Heinrich Himmler.

- Kurt Wetzel as Herman Göring.

- Joachim Pape as Martin Bormann.

- Fred Alexander as Elyesa Bazna.

- Gerd Ehlers as General Werner Kempf.

- Willi Wenghöfer as General who interrogated Maximov.

- Peter Marx as General Theodor Busse.

- Hans-Ulrich Lauffer as General Gustav Schmidt.

- Erich Gerberding as Field Marshal Ernst Busch.

- Ralf Böhmke as General Adolf Hamann.

- Wilfried Ortmann as General Friedrich Olbricht.

- Hans-Edgar Stecher as Werner von Haeften.

- Werner Wieland as General Ludwig Beck.

- Otto Dierichs as Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben.

- Paul Berndt as Colonel Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim (III)/Arthur Axmann (IV-V).

- Max Bernhardt as Doctor Carl Friedrich Goerdeler.

- Manfred Bendik as Major Ernst John von Freyend.

- Ernst-Georg Schwill as SS receptionist.

- Rolf Ripperger as General Adolf Heusinger.

- Fritz-Ernst Fechner as Colonel Heinz Brandt.

- Willi Schrade as Lieutenant Heurich.

- H. Schelske as General Friedrich Fromm.

- Hinrich Köhn as Major Otto Ernst Remer.

- Ulrich Teschner as Lieutenant Bock.

- Regina Beyer as Goebbles' secretary.

- Herbert Körbs as General Heinz Guderian.

- Joseph (Sepp) Klose as Karl Wolff.

- Fred Mahr as General Sepp Dietrich.

- Gert Hänsch as General Helmut Weidling.

- Hans-Hartmut Krüger as General Hans Krebs.

- Peter Friedrich as Lieutenant who accompanied Krebs.

- Werner Pfeifer as Vice-Admiral Hans-Erich Voss.

- Erwin Felgenhauer as Ludwig Stumpfegger.

- Otto Busse as Heinz Linge.

- Gerd Steiger as Wilnie.

- Ingolf Gorges as the soldier captured by Tzvetaev.

- Günther Polensen as priest.

- Georg-Michael Wagner as Walter Wagner.

Polish actors

- Jan Englert as Jan Wolny.

- Stanisław Jaśkiewicz as Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

- Daniel Olbrychski as Henryk.

- Barbara Brylska as Helena.

- Wieńczysław Gliński as 'Blacksmith'.

- Ignacy Machowski as stableman.

- Michał Adamczewski as German officer.

- Cezary Julski as drunken German officer.

- Tadeusz Schmidt as General Zygmunt Berling.

- Maciej Nowakowski as Alexander Zawadzki.

- Franciszek Pieczka as Pelka.

Others

- Ivo Garrani as Benito Mussolini.

- Erno Bertoli as Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Pouyade.

- Florin Piersic as Otto Skorzeny.

- B. White as Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen.

Production

Background

Yuri Ozerov studied at the Lunacharsky Theater Institute when he was conscripted into the Red Army at 1939. His return to civilian life was postponed on the outbreak of the war with Germany. Ozerov told his wife that during the Battle of Königsberg, he swore that if he will survive, one day he would tell of his experiences.[2] After demobilization, Ozerov became a director in the Mosfilm studios, making his first film at 1952. During the 1960s, he was dismayed and offended by several Western films that he perceived as belittling the role of the Red Army during the Second World War.[3] The Soviet government shared Ozerov's sentiments, especially in regards to the 1962 film The Longest Day.[4][5] At October 1965, in a meeting of officials from the Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Culture and Ministry of Finance, it was decided to create a "monumental epic" that would demonstrate the USSR's contribution to the victory. Ozerov was chosen to direct it.[6]

In the Brezhnev-era Soviet Union, the commemoration of the war against Germany was awarded unprecedented importance. At a time of growing skepticism toward the Communist system, the memory - or, as the historian Nina Tumarkin called it, "cult" - of the Great Patriotic War was to provide inspiration for a new generation and remind them of the hardships their parents faced.[7] Historian Denise J. Youngblood dubbed Liberation as the "Brezhnev era's canonical war film", writing that it was "clearly designed to buttress the war cult."[8]

The Second World War was always a crucial topic for Soviet filmmakers. Immediately after the war, propaganda epics like The Fall of Berlin (1949) presented it as an heroic, collective effort of the people that was brilliantly led by Stalin. After his death, the Khruschev Thaw enabled filmmakers to depict the war as a personal, inglorious experience of the individual participants - with films as Ivan's Childhood or Ballad of a Soldier. The Brezhnev administration supported a return to a more conservative style, presenting the war as a noble, ideological struggle once more.[1][9][10] In an essay on the series, Dr. Lars Karl wrote: "In this context, Liberation held special importance. Even only in quantitative measures, it overshadowed anything made hitherto".[1]

Development

The work on the series commenced at 1966.[11] Ozerov was closely supervised - Mikhail Suslov was involved in the production,[12][13] as well as General Alexei Yepishev, the Chief of the Soviet Armed Forces' Political Directorate. Lazar Lazarev, a member of the Soviet Filmmakers Association, wrote in his recollections of the time: "Liberation ...was forced down from above, from the Ideological Departments".[4] From the very beginning, it was made clear that the films should not deal with the darker chapters of World War II, such as the defense of Moscow and Stalingrad, but only with the Red Army's unbroken string of victories from the Battle of Kursk and onwards.[2][14]

At first, two prominent authors, Konstantin Simonov and Viktor Nekrasov, were offered to write the story. Both saw Liberation as an effort to rehabilitate Stalin, and declined.[4] During the Khruschev Thaw, in the aftermath of the XX Party Congress and De-Stalinization, Eastern Block films rarely depicted Stalin, if at all. Scenes featuring him were edited out from many older pictures.[15] Liberation presented Stalin as the Supreme Commander, his first major appearance on screen since the Secret Speech[16] - a token to the Brezhnev Era softer view of him,[4][14] in comparison with the Khruschev years.[17] Still, his character did not occupy a central role as it had done in the films produced during his reign.[9][14] Ozerov later claimed that he never included the controversial figure in the script, and had to shoot the Stalin scenes secretly, at night. He told interviewer Victor Matizen that the "State Secretary for Cinematography almost had a seizure when he found out."[18]

Another contentious character was that of General Andrey Vlasov. Liberation presented him for the first time in Soviet cinema.[12][18][19] It was the most secretive role in the cast, referred to only as "the General" on set[2] and not mentioned in the credits.

After Nekrasov's and Simonov's refusal, Yuri Bondarev and Oscar Kurganov were tasked with writing the script. Originally, the series was supposed to be a purely historical, documentary-like trilogy called the Liberation of Europe and consisting of Europe-43, Europe-44 and Europe-45. Fearing that this style would damage the films' popularity, it was decided to combine fictional characters into the plot. Bondarev wrote the live action scenes; The Dniepr bridgehead storyline was based on his book The Battalions Request Fire. Kurganov wrote the historical parts, featuring the leaders and generals. Those sections were intentionally filmed in black-and-white, to resemble old footage.[20] Ozerov wanted the films to portray the war both from the common soldier's standpoint and from a bird's-eye view upon the major occurrences: "There were many films about the war, but they were films that depicted isolated episodes of it... I wanted to tell of the war as a whole, to portray it as it was".[21] The script of the first two parts was completed by the end of 1966, and the producers began preparing to commence filming shortly after.[22]

International involvement

The final script had a broad scope, dealing not only with the Soviet side but also dedicating attention to events in other countries, like the Battle of the Sutjeska[a 1] or the actions of the Polish Resistance. Foreign film studios were invited to take part in the production, beside Mosfilm: The East German company DEFA, The Yugoslav Avala Film and the Italian Dino de Laurentiis Cinematografica. Zespół Filmowy Start, the first Polish film studio to participate in the co-production of Liberation, was closed at April 1968, in the crackdown on the Polish media after the March Events.[23] It was replaced by Przedsiębiorstwo Realizacji Filmów-Zespoły Filmowe (PRF-ZF), established after the political turmoil was over (on 1 January 1969).[24] Studio Start appears in the credits of films I and II. The dialog in the non-Soviet scenes is in the local languages.

Military involvement

Ozerov asked Marshal Zhukov to be the films' chief military consultant, and the old commander agreed. However, Zhukov was a political pariah at the time, and the establishment did not approve of the nomination. The Marshal suggested Army General Sergei Shtemenko to take the position, and the Warsaw Pact Forces Chief-of-Staff received it. In spite of this, Ozerov consulted with Zhukov unofficially,[a 2] and the Marshal provided him with the draft of his memoirs.[18]

Beside Shtemenko, the producers brought in several other veterans of the war as advisors: Colonel-General Alexander Rodimtsev, Colonel-General of the Armored Corps Grigory Oriol, Lieutenant-General of the Aviation Sergei Siniakov and Vice-Admiral Vladimir Alexeyev. Member of the Sejm and retired Colonel Zbigniew Załuski served as the consultant for matters relating to the Polish People's Army.[25] National People's Army Colonel Job von Witzleben, who served in the Wehrmacht as a Major, assisted with the German military issues.[26]

150 Soviet Army tanks, allocated by Defense Minister Rodion Malinovsky before the filming began, were involved in the battle scenes,[2] alongside military aircraft, artillery and thousands of soldiers.[6] The troops were lent as extras by the Military districts of Moscow, Kiev, the North Caucasus and Belarus, the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany and the Baltic Fleet. Polish Army soldiers took part in the later films, as well.[25]

Casting

A major obstacle facing the producers was that most of the Soviet leadership took part in the war; Many high-ranking officers and politicians were portrayed in the films with their wartime ranks, and the actors depicting them had to receive the models' blessing.[2]

Ozerov lengthily dwelt on the question who would be cast as Zhukov, until the Marshal himself provided him with a solution: he told the director that he recently watched The Chairman and thought that the main protagonist, whose name he did not know, would be fit to for the task. Thus, Mikhail Ulyanov received the role.[27] Marshal Ivan Konev was irritated by Yuri Leghkov, who depicted him in the first two parts. He demanded that Ozerov would replace him by someone else, complaining that the actor was constantly bothering him with questions. Vasily Shukshin was called to substitute Leghkov.[19]

For the character of Captain Tzvetaev, Ozerov chose the young Nikolay Olyalin, an actor of the Krasnoyarsk Children Theater. Olyalin had received several offers to appear in other films, but the theater managers dispersed of them, fearing that he would leave their institute. One of the theater employees told Olyalin of Ozerov's offer. To be exempted from his work, the actor claimed he was sick. Then, he boarded a plane to Moscow.[28]

An assistant-director saw the Kazakh SSR's People's Artist Yuri Pomerantsev in theater, and suggested him for the role of Vlasov.[2] Pomerantsev had difficulties finding any material on the Russian Liberation Army's commander.[29] Bukhuti Zaqariadze, People's Artist of the Georgian SSR, was selected to appear in the sensitive role of Joseph Stalin. Vasily Shukshin recounted that upon seeing Zaqariadze in the Stalin costume, General Shtemenko instinctively stood to attention and saluted.[20]

According to the memories of Dilara Ozerova, East German actor Fritz Diez was reluctant to portray Hitler; Diez, a communist who left Nazi Germany in the 1930s, had already appeared as Hitler in three other films and feared becoming "a slave to one role".[2][18] Diez's wife, Martha, appeared as the old woman who served coffee to Tzvetaev in Berlin. The Italian Ivo Garrani played Benito Mussolini.[25]

Props and costumes

When the making of the film had begun, assistants were dispatched to look for equipment used during the war.[2] The producers searched in vain for real Tiger I and Panther tanks, so they could use them in close-up shooting. Eventually, replicas of 10 Tigers and 8 Panthers (converted from T-44 and IS-2 tanks respectively) were produced in a Soviet tank factory in Lvov. Beside those, many T-55's, T-62's and IS-3's - models that were developed after the war - can be clearly seen in the film, painted as wartime German or Soviet tanks. All German trucks were actually masqueraded Ural-375D vehicles.[30]

Dilara Ozerova, the director's wife and the film's costume designer, had to have hundreds of German uniforms sewn. The German military decorations were reproduced in Mosfilm's workshops. The helmets worn by the extras were manufactured of plastic, for lighter weight. Stalin's own tailor was contacted, and Bukhuti Zaqariadze's costume was made by him.[2]

Principal photography

The producers considered filming the Fire Bulge in Kursk, but the old battlefield was littered with unexploded ammunition. Therefore, a special set was constructed in the vicinity of Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi where Art Director Alexander Myaghkov was free to use live explosives. The combat scenes in the first two parts were shot there,[20] at the summer of 1967.[31] 3000 troops, 100 tanks, 18 military aircraft and 2000 artillery pieces were used to recreate the Battle of Kursk.[6] 30 kilometers of trenches were dug to resemble the wartime fortifications. Ozerov supervised the set from a specially-built tower, using a handkerchief to signal the engineers when to detonate the charges. On one occasion, the director absentmindedly blew his nose, and "one and half tons of TNT went off".[18] The outdoor photography for Main Blow took place in Lithuania, near Pabradė, since the marshes in Belarus - the location of the 1944 battles depicted in the film - were being drained. The Mussolini parts were shot in Rome, while the Yalta Conference was filmed in the Livadia Palace.[20]

Filming also took place in Poland. The scenes in Warsaw were shot in the city's Castle Square and at the Służewiec neighbourhood.[32] The 20th July 1944 assassination attempt was filmed in the original Wolfsschanze,[33] where Diez and Giese, in costumes, shocked a group of tourists. On seeing a photo of Ozerov and 'Hitler' hugging on the set, a maid in a Potsdam hotel caused a pandemonium, convinced the director was an old friend of the genuine dictator.[2]

With the help of the East German government, the scenes in Berlin were mostly shot in the city itself. Foreign Minister Otto Winzer had authorized the producers to use the ruins of the Gendarmenmarkt.[34] Ozerov, accompanied by a crew of some 2000 people,[18] cordoned off a part of the area and used an old, abandoned cathedral to substitute for the Reichstag. The hoisting of the Victory Banner was shot atop the Haus der Technik in the Wilhelmstraße, in the city's center. Indoor fighting was filmed in Mosfilm's studios, and the U-Bahn scene took place in Moscow's metro - where Myaghkov rebuilt the Kaiserhof station.[2][20]

Approval

The Fire Bulge was completed on late 1968. A special screening was made to General Sergei Shtemenko. Bondarev invited Lazarev to attend. In his memoirs, the writer recalled that Shtemenko had only two, "rather bizarre" comments to make: first, a scene showing a soldier entertaining local girls in his tank had to be removed; Second, when seeing the actor portraying him with Major General ranks, he claimed he was already a Lieutenant General at the time. Ozerov answered that according to their material, he was not.[4] The aforementioned scene does not appear in the film.

A more important pre-release viewing had to be held for Defense Minister Andrei Grechko and General Alexei Yepishev. After the screening ended, the generals headed for the exit without saying a word. Ozerov asked for their opinion; Grechko answered, "I will not say a word to you!" and left the room. The film had to be edited four times before it was authorized for public screening on 1969, together with the already finished second part, Breakthrough.[18]

Reception

Distribution

The Fire Bulge and Breakthrough were released on 7 May 1970, two days before the 25th Victory Day, and the audiences viewed them in a single screening session. The third, exceptionally long sequel Main Blow was distributed to the cinemas in July 1971. Finally, the two concluding films, The Battle of Berlin and The Last Assault were released in a single band on November 1971.[35] In the West, a shorter, 110 minutes long version of The Fire Bulge/Breakthrough was disseminated.[36][37] In the English-speaking world, it was titled The Great Battle. The film was screened in the United Kingdom at 1971,[38] but reached the United States only at October 1974, where it was distributed by Columbia Pictures.[37][39] The films were distributed in 115 countries[40] and were received especially well in France and Japan.[2]

Box office

It was reported that the Communist Party instructed all of it members to purchase tickets for Liberation;[41] yet, The Fire Bulge/Breakthrough was watched by only 56 million viewers, falling short of the producers' expectations.[8] Still, it became the highest-grossing Soviet film of 1970. Main Blow had 35.8 million tickets sold for it, falling to the slot of the 9th highest-grossing film of 1971. The Battle of Berlin/Last Assault was viewed by 28 million people, deteriorating further down to 16th place on the Soviet box office in 1972.[42] The Russian author Igor Muskyi estimated that worldwide, Liberation was watched by more than 400 million people.[20]

Awards

The Fire Bulge/Breakthrough was screened outside the competition in the 1970 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, and Yuri Ozerov received a special prize of the Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship Society.[43]

Ozerov, Bondarev, Cinematographer Igor Slabnevich and Art Director Alexander Myaghkov were all awarded the Lenin Prize in 1972 for their work on Liberation.[20] The films won the Best Film award at the 1972 Tiflis All-Union Film Festival, and Ozerov received the Polish-Soviet Friendship Society's Silver Medal in 1977.[44] The series was submitted by the Soviet Union as a candidate for the Best Foreign Language Film in the 46th Academy Awards, but not nominated.

Contemporary response

Liberation was strongly supported by the Soviet government. The series was branded as an "epic" before the shooting began.[4] The press excessively promoted the film, and war veterans published columns that praised its authenticity.[14] When Ozerov briefed delegates of the 24th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union about Liberation, he was welcomed with applause.[45] The readers of the journal Sovietsky Ekran, the State Committee for Cinematography's official publication, chose The Direction of the Main Blow as the best film of 1971.[14][46] As late as 1986, the state-approved Soviet encyclopedia of cinema cited Liberation as correcting the "falsification of history" presented in The Longest Day.[4][47]

The films were noted for the scales of the production: at 1977, Film critics Mira and Antonin Liehm cited it alongside Waterloo and War and Peace as foremost among Soviet "monumental films, which, with the expenditure of immense amounts of money, brought... history to the screen."[9] Soviet critic Rostislav Yurenev "praised the meticulously recreated battle scenes",[10] which were referred to as "gigantic" by the Liehm couple.[9] A Der Spiegel review from 1971 praised Ozerov for portraying the German side "with due consideration" for details.[36]

However, the series was not seen as an artistic achievement. Ozerov wrote an article in the February 1971 issue of the Soviet magazine Art of Cinema, in which he declared that his film should be considered as one of the best dealing with the theme of the Great Patriotic War, along the likes of the 1964 The Living and the Dead. Two months later, the important author Semion Freilikh completely ignored Liberation when discussing the genre of war films in the same magazine. Denise Youngblood wrote that this was no coincidence.[14] Eventually, the series was never selected to appear on the official lists of the greatest World War II films, which were compiled on every fifth Victory anniversary.[8] Lazar Lazarev wrote in his memoirs that Liberation was a return to the style of the propagandistic films before the Thaw. When Bondarev asked for his opinion at 1970, he called the film "a modern version of the Fall of Berlin".[4]

Critics abroad were scathing, as well. A year after the Last Assault was released, David Robinson called Liberation a "hollow, spectacular, monumental display."[48] Mira and Antonin Liehm dubbed it as "entirely sterile" and "almost reminiscent of the 'Artistic Documentary' period" - the era of the Stalinist epics.[9] Author Ivan Butler simply described it as a "stranded whale of a film."[49]

Denise J. Youngblood wrote that, considering the "unprecedented" public relations campaign the film received and the forced attendance of viewers, the last part's success of drawing only 28 million moviegoers was "almost pitiable". She attributed this, partially, to the "grandiose scale" of the films, which made it hard to maintain the interest of the audience. Youngblood concluded that the series was a "relative failure".[14]

Critical analysis

Liberation is still acclaimed for its size; Martin J. Manning and Clarence R. Wyatt wrote that, among the films of the Brezhnev era, the series was "standing out due to its massive scale, length and sheer volume."[50] Lars Karl claimed that "it was a gigantic work... The cinematic monumentality was to prove the Soviet Union's might."[1] In an essay on Soviet films, Denise J. Youngblood called Liberation the "most grandiose Soviet WWII picture".[10]

Historian Lisa A. Kirshenbaum assessed that in comparison to more sincere Great Patriotic War films, like The Ascent or The Cranes Are Flying, the "heroic, if not kitschy" Liberation conformed to the "Cult of the Great Patriotic War".[51] Lars Karl regarded it as one of the films ushering the Brezhnev Stagnation into Soviet cinema, in which "a new conservatism and sharpened censure molded the cinematic image of the war into conventional patterns."[1]

Denise J. Youngblood stated that the films - depicting the protagonists as human and imperfect - were still influenced by the Khruschev Thaw's artistic freedom, writing that: "It is, however, important to stress that Ozerov was far from a 'tool' of war cult propaganda... Liberation is a much better film than critics allowed".[8] When interviewing Nikolay Olyalin, journalist Dmitry Gordon commented that unlike the Stalinist war films, Liberation showed Red Army soldiers panicking and breaking under pressure, depicting the "Blood, death, sweat and tears" of war.[28] German author Christoph Dieckmann wrote that "Despite of all the propaganda, Liberation is an anti-war film, a memento mori to the uncountable lives sacrificed for victory."[52]

Historical accuracy

The sociologist Lev Gudkov saw the series as a succinct representation of the Soviet official view on the war's history: "The dominant understanding of the war is shown in the film epic Liberation... All other versions only elaborated on this theme." He characterized this view as one that allowed "a number of unpleasant facts" to be "repressed from mass consciousness".[53]

Dr. Lars Karl claimed that "Ozerov wanted to show that Europe's liberation from Fascism was enabled by the Red Army... And therefore, the Soviet Union had a right to have a say in the matters of Europe." Karl noted that Roosevelt and Churchill are depicted as "paper tigers" who are keen to reach a settlement with Hitler; in the Battle of Berlin, Stalin informs the Western leaders that he knows of the covert Dulles-Wolff dealings when they assemble in the Yalta Conference, on 4 February 1945 - a month before the actual negotiations took place; Averell Harriman officially notified Vyacheslav Molotov on the matter beforehand. Karl also wrote that no mention is made of the Stalin-Hitler Pact.[1] Polish author Łukasz Jasina commented that the Bug River, the line along which Poland was partitioned between the Soviet Union and Germany at 1939, is spoken of as the Polish border already during 1944 - although the USSR annexed the eastern territories of Poland only after the war.[54] Russian historian Boris Sokolov wrote that the film's depiction of Battle of Kursk was "completely false" and the German casualties were exaggerated.[55] Liberation presents the civilian population in Berlin welcoming the Red Army; German author Jörg von Mettke wrote that the scene in which the German women flirt with the Soviet soldiers "might have happened, but it was mostly otherwise."[56] General Gustav Schmidt, who committed suicide rather than to be captured by the Soviets, is shown to have done so after disappointing von Manstein and failing to defeat the enemy.

Grigory Filaev called the films an "encyclopedia of myths", and claimed that they spread the falsehood according to which Stalin ordered to capture Kiev before the eve of the 26th Anniversary of the October Revolution.[12] Victor Suvorov wrote that in reality, Zhukov had objected to Rokossovsky's decision to launch a preemptive artillery strike in Kursk, and that the latter even wrote to the producers a letter protesting the decision to portray the events otherwise.[13] Yakov Dzhugashvili's daughter, Galina, claimed that the phrase "I will not trade a Field Marshal for a soldier", that is strongly associated with Yakov's story,[12] was never uttered by her grandfather and is "just a quote from Liberation".[57] Yakov Dzhugashvili's appearance in The Fire Bulge was anachronistic: he is depicted meeting General Vlasov on 5 July 1943. Yakov died at 14 April 1943.

Legacy

Liberation won great acclaim for Yuri Ozerov, both in the Soviet Union and abroad.[58] Until the end of his career, the director devoted himself to the subject of the Second World War.[2] Several actors continued to depict their characters from Liberation in Ozerov's other works: Mikhail Ulyanov and Gerd Michael Henneberg, for example, appeared as Zhukov and Keitel also in Soldiers of Freedom (1977), Battle of Moscow (1985) and Stalingrad (1989).

The series is regularly broadcast on the Russian television's Channel One during Victory Day.[59] At August 2001, shortly before Yuri Ozerov's eightieth birthday, Russian Minister of Culture Mikhail Shvidki announced that the series would be restored as had been done to War and Peace.[60] At 2003, the films were remastered by a team from Mosfilm, headed by Anatoly Petritzky, and released on DVD format.[25][61][62] Some footage from the original version was not included for technical reasons, and the new edition is shorter.[19]

During a presidential interview for the 2010 Victory Day, when asked about the war's casualties, Dmitry Medvedev told: "I recall the lines in the end of Liberation... On the screen, it was written that more than twenty million Soviet people lost their lives."[63] At an official debate on the commemoration of World War II held in the Federation Council of Russia, deputy Oleg Panteleev commented: "I hope that the youth of today would read some of those literary works (on the war), listen to Shostakhovich and watch Liberation".[64] Member of the Verkhovna Rada and former Ukrainian Foreign Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk announced that he would send the series to Vladimir Putin as a new year's gift for 2011, claiming the films demonstrate Ukraine's importance for the victory in the war.[65]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Karl, Lars (May 2005). "Die Schlacht um Berlin im sowjetischen Monumentalepos Befreiung [The Battle of Berlin in the Soviet monumental epic Liberation]" (in German). Zeitgeschichte Online. http://www.zeitgeschichte-online.de/zol/_rainbow/documents/pdf/russerinn/karl_befr.pdf. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bukin, Alexei (June 2005). "КИНОЛЕТОПИСЬ ВЕЛИКОЙ ВОЙНЫ [Cinema Chronicler of the Great War]" (in Russian). Petrovskyi Vedomosti. http://www.p-vedomosti.ru/date34.htm. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Antonina Kriukova (17 February 2001). "Последний бой, он трудный самый [The Last Battle is the Hardest]" (in Russian). Tribuna. http://www.tribuna.ru/news/2011/02/17/Poslednij_boj_on_trudnyj_samyj/. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lazarev, Lazar (2001). "Записки пожилого человека [Memoirs of an Old Man]" (in Russian). magazines.russ.ru. http://magazines.russ.ru/znamia/2001/6/lazar-pr.html. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Louis Menashe (2010). Moscow Believes in Tears: Russians and Their Movies. Washington D.C.: New Academia Publishing. ISBN 0984406204. page 94.

- ^ a b c various, authors (2005). Film-Dienst: Volume 59, Issues 1-7. Katholische Filmkommission für Deutschland. pp. 45–47. ISSN 0720-0781. http://books.google.com/books?ei=L9aqTdj2Fs-JhQfK29XHCQ&ct=result&id=EmxZAAAAMAAJ&dq=befreiung+film+dienst+witzleben&q=hardliner#search_anchor. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Tumarkin, Nina (1995). The Living and the Dead: The Rise and Fall of the Cult of World War II in Russia,. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465041442.

- ^ a b c d Frank Biess, Robert G. Moeller (editors) (2010). Histories of the Aftermath: The Legacies of the Second World War in Europe. Berghan Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-732-7. pages 131-3.

- ^ a b c d e Miera Liehm, Antonin J. Liehm (1977). The Most Important Art: Soviet and Eastern European Film After 1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04128-3. pages 312-314.

- ^ a b c J. Youngblood, Denise (June 2001). "A War Remembered". American Historical Review. http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/106.3/ah000839.html#REF29. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ unknown, author (1970). Ekran. State Committee of Cinematography. http://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&tbo=1&q=%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B0+%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%B4+%D1%84%D0%B8%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%BC+%C2%AB%D0%9E%D1%81%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5%C2%BB+%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%8C+%D0%B2+1966+%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%83.+%D0%98+%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B5+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B5+%D1%8D%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE+%D0%B1%D1%8B%D0%BB%D0%B8+%D1%81%D0%BD%D1%8F%D1%82%D1%8B+%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B2%D1%8B%D0%B5+%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B4%D1%80%D1%8B+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%B9+%D1%87%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8+%E2%80%94+%C2%AB%D0%91%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B2%D1%8B+%D0%B7%D0%B0&btnG=Search+Books. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d Aleksander Diukov and others (2008). Великая оболганная война-2 (The Great War Slander-2). Exmo Press. ISBN 978–5–699–25622–8. pages 19-22.

- ^ a b Viktor Suvorov (2007). The Shadow of Victory. Stahlker Press. ASIN B00270ZSNU. Chapter 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Denise J. Youngblood (2007). Russian War Films: On the Cinema Front, 1914-2005. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700614893. pages 158-162.

- ^ Liehm, page 204.

- ^ Birgit Beumers (2009). A History of Russian Cinema. Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1845202156. page 150.

- ^ On the official view of Stalin in the Brezhnev years, See, for example: Roman Brackman (2001). The Secret File of Joseph Stalin. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0-203-01823-0. page 347.

- ^ a b c d e f g Matizen, Victor (16 October 2001). "Человек, который дважды брал Европу [The Man Who Took Europe Twice]" (in Russian). Film.ru. http://www.film.ru/article.asp?id=2815. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ a b c ""Освобождение":Рейхстаг штурмовали частями [Liberation:They Stormed the Reichstag with Intervals]" (in Russian). tvcenter.ru. 5 May 2007. http://www.tvcenter.ru/programm/cinema/Osvobozhdenie-Reihstag-shturmovali-chastjami/. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Igor Muskyi (2007). 100 великих отечественных кинофильмов (100 Great Homeland Films). Moscow: Veche Press. ISBN 9785953323437.Chapter 75: Liberation (available on the book's official website).

- ^ "Озеров Юрий. 90 лет со дня рождения [Yuri Ozerov, 90 Years to his Birth]" (in Russian). tvkultura.ru. Russia K. 26 January 2001. http://www.tvkultura.ru/news.html?id=85598&cid=180. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Ozerov, Yuri; Bondarev, Yuri. Освобождение (киноэпопея). Iskustvo Press, Moscow. p. 208. OCLC 28033833. http://www.google.com/search?hl=iw&tbo=1&tbm=bks&q=%D0%98%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BA%2C+%D0%BA+%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%86%D1%83+1966+%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B0+%D1%81%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B9+%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B2%D1%8B%D1%85+%D0%B4%D0%B2%D1%83%D1%85+%D1%84%D0%B8%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%B2+%D0%B1%D1%8B%D0%BB+%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%BD%2C+&oq=%D0%98%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BA%2C+%D0%BA+%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%86%D1%83+1966+%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B0+%D1%81%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B9+%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B2%D1%8B%D1%85+%D0%B4%D0%B2%D1%83%D1%85+%D1%84%D0%B8%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%B2+%D0%B1%D1%8B%D0%BB+%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%BD%2C+&aq=f&aqi=&aql=&gs_sm=e&gs_upl=17945l19694l0l2l2l0l0l0l1l387l387l3-1. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Zespół Filmowy Start [Film Home Team]" (in Polish). Filmpolsky.pl. 1998. http://filmpolski.pl/fp/index.php/1110098. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ "Przedsiębiorstwo Realizacji Filmów Zespoły Filmowe [Enterprise Implementation Film Film Groups]" (in Polish). Filmpolsky.pl. 1998. http://www.filmpolski.pl/fp/index.php/111015. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d All the specified details appear in the films' credits, except the supporting military formations, which are credited in the intros of every part. "Освобождение. Фильм 1. Огненная дуга [Liberation, Film 1:The Fire Bulge]" (in Russian). Kinoros.ru. http://www.kinoros.ru/db/movies/436/full.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.; "Освобождение. Фильм 2. Прорыв [Liberation, Film 2:Breakthrough]" (in Russian). Kinoros.ru. http://www.kinoros.ru/db/movies/437/full.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.; "Освобождение. Фильм 3. Направление главного удара [Liberation, Film 3:Direction of the Main Blow]" (in Russian). Kinoros.ru. http://www.kinoros.ru/db/movies/438/full.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.; "Освобождение. Фильм 4. Битва за Берлин [Libeation, Film 4: Battle of Berlin]" (in Russian). Kinoros.ru. http://www.kinoros.ru/db/movies/439/full.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.; "Освобождение. Фильм 5. Последний штурм [Liberation, Film 5: The Last Assault]" (in Russian). Kinoros.ru. http://www.kinoros.ru/db/movies/440/full.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Niemetz, Daniel (2006). Das feldgraue Erbe: die Wehrmachteinflüsse im Militär der SBZ/DDR. Christoph Links Verlg. p. 253. ISBN 978-3861534211. http://books.google.com/books?id=iZ-TqnovGvoC&pg=PA253&dq=befreiung+job+von+witzleben&hl=en&ei=B9aqTcD1Ls-7hAfEr9yZCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDYQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=befreiung%20job%20von%20witzleben&f=false. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Kichin, Valery (28 March 2007). "Ульянов. Занавес [Ulyanov, Fall of the Curtain]" (in Russian). Rossiskaya Gazeta. Vakhtangov.ru. http://www.vakhtangov.ru/history/persons/uliyanov/9389/. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ a b Gordon, Dmitry (9 August 2005). "Сильные духом [Strong Spirit]" (in Russian). Bulwar Gordona. http://www.bulvar.com.ua/arch/2005/16/42f8c07e255d8/. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Yakushev, Yuri (February 2008). "Есть такая профессия [There is Such A Profession]" (in Russian). Afisha magazine. http://www.afisha.kz/journals/2008/56/584%20pomerantsev. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ "Osvobozhdenie". Internet Movie Cars Database. http://www.imcdb.org/movie_151852-Osvobozhdenie.html. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Ozerov, Yuri; Bondarev, Yuri. Освобождение (киноэпопея). Iskustvo Press, Moscow. p. 218. OCLC 28033833. http://books.google.com/books?ei=W_-vTZsvxJc6nb-4owk&ct=result&hl=iw&id=z4QNAAAAIAAJ&dq=%D0%9E%D1%81%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5+%28%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%8D%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%8F%29+1967&q=1967#search_anchor. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Oswobozdienije [Deliverance]" (in Polish). Filmpolsky.pl. 1998. http://filmpolski.pl/fp/index.php/128980. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Neumärker, Uwe. "Wolfsschanze": Hitlers Machtzentrale im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Christoph Links Verlag. p. 179. ISBN 978-3861534334. http://books.google.com/books?id=IRokztzGbyQC&pg=PA80&dq=wolfsschanze+befreiung&hl=en&ei=-eKqTb_hHcTDhAfbrfD9Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAA#v=snippet&q=Oserow&f=false. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Stefan Zahlmann (2010). Wie im Westen, nur anders: Medien in der DDR. Panama Verlag. ISBN 978-3938714119. page 231.

- ^ The release dates are given in kinopoisk.ru: "Освобождение: Огненная дуга [Liberation: The Fire Bulge]" (in Russian). Kinopoisk.ru. http://www.kinopoisk.ru/level/1/film/94296/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.; "Освобождение: Прорыв [Liberation:breakthrugh]" (in Russian). Kinopoisk.ru. http://www.kinopoisk.ru/level/1/film/392539/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.; "Освобождение: Направление главного удара [Liberation: Direction of the Main Blow]" (in Russian). Kinopoisk.ru. http://www.kinopoisk.ru/level/1/film/46318/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.; "Освобождение: Битва за Берлин [Liberation: The Battle of Berlin]" (in Russian). Kinopoisk.ru. http://www.kinopoisk.ru/level/1/film/392540/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.; "Освобождение: Последний штурм [Liberation: The Last Assault]" (in Russian). Kinopoisk.ru. http://www.kinopoisk.ru/level/1/film/392541/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b uncredited author (18 January 1971). "Großes Gefecht [Greatest Battle]" (in German). Der Spiegel. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-43375335.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ a b Blum, Daniel C. (1975). Screen world, Volume 26. Crown Publishers. p. 210. ISSN 0080-8288. http://books.google.com/books?ei=IeaqTZzUMYeXhQeU-dnxDA&ct=result&id=iGcEAQAAIAAJ&dq=yuri+ozerov+great+battle&q=great+battle+ozerov#search_anchor. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ various, authors (1971). Punch, Volume 261. Punch Publications Ltd.. p. 261. ISSN 0033-4278. http://books.google.com/books?ei=IeaqTZzUMYeXhQeU-dnxDA&ct=result&id=ECMIAQAAIAAJ&dq=yuri+ozerov+great+battle&q=yuri+ozerov+#search_anchor. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ various, authors (1974). The Review of the news, Volume 10. Review of the News, inc. p. 25. ISBN 0034-6802. http://books.google.com/books?id=9_oMAQAAMAAJ&q=yuri+ozerov+great+battle&dq=yuri+ozerov+great+battle&hl=en&ei=IeaqTZzUMYeXhQeU-dnxDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CEQQ6AEwCA. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Galina Shilova, Irina Dolmatovskaya (1979). Who's Who in the Soviet Cinema. Moscow: Progess Publishing House. ASIN B000J2LJEA. page 214.

- ^ Richard Stites (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society Since 1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521362148. page 169.

- ^ The ticket sales appear in Denise Youngblood's books, but the rankings on the national box office come from:"Освобожде́ние [Liberation]" (in Russian). Kinoexpert.ru. 22 October 2007. http://www.kinoexpert.ru/index.asp?comm=4&num=1743#1. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ various, authors (1972). Экран. All-Union Institute of Cinema Research. p. 242. OCLC 472805656. http://books.google.com/books?ei=VfOvTd_TE8igOqnA3KcJ&ct=result&hl=iw&id=b9xkAAAAMAAJ&dq=%D0%93%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B0+%D0%9E%D1%81%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5+%28%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%8D%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%8F%29&q=+%D1%85%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%BA%D0%BE-%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B9+%D0%B4%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B6%D0%B1%D1%8B#search_anchor. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ .. "Освобожде́ние [Liberation]" (in Russian). Russiancinema.ru. http://www.russiancinema.ru/template.php?%20dept_id=3&e_dept_id=2&e_movie_id=4412. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Lezin, A.N. (9 October 2001). "СДЕЛАННЫЕ В СССР [Made in the USSR]" (in Russian). Duel Magazine. http://www.duel.ru/200141/?41_7_1. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ "Победители конкурса журнала "Советский экран" [Sovietsky Ekran Competition Winners]" (in Russian). akter.kulichki.com. October 1983. http://akter.kulichki.com/se/10_1983. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Afanaseev, Yuri; Yutkevich, Sergei (1986). Кино: энциклопедический словарь. Great Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 157. http://books.google.co.il/books?id=yORnAAAAMAAJ&q=%D0%BF%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B5+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5,+%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%B7%D0%BD%D0%BE+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B7%D1%8B%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%8E%D1%89%D0%B5%D0%B5+%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%8B%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%8F+%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B9%D0%BD%D1%8B&dq=%D0%BF%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B5+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5,+%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%B7%D0%BD%D0%BE+%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B7%D1%8B%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%8E%D1%89%D0%B5%D0%B5+%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%8B%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%8F+%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B9%D0%BD%D1%8B&hl=iw&ei=Y4mtTY72M4e0hAeP2uGgDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ David Robinson (1973). World Cinema: A Short History. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 978-0413291905. page 388.

- ^ Butler, Ivan (1974). The war film. A. S. Barnes & Co. Inc and Tantivy Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0498013959. http://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&tbo=1&q=yuri+ozerov+stranded+whale&btnG=Search+Books. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Martin J. Manning, Clarence R. Wyatt (editors) (2010). Encyclopedia of Media and Propaganda in Wartime America. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598842272. page 519.

- ^ Kirshenbaum, Lisa (2006). The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad 1941-45. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521863260. page 180.

- ^ Christoph Dieckamann (2005). Rückwarts immer: deutsches Erinnern, Erzählungen und Reportagen. Christoph Links Verlag. ISBN 3-86153-350-2. page 53.

- ^ Gudkov, Lev (3 May 2005). "The Fetters of Victory: How the War Provides Russia With Its Identity". Eurozine. http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2005-05-03-gudkov-en.html#footNote13. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Łukasz Jasina (2007). Wyzwolenie (1968-1975) Jurija Ozierowa jako prezentacja oficjalnej wersji historii II wojny światowej w kinematografii radzieckiej. Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. ISBN 978-83-60695-09-8. page 7.

- ^ Sokolov, Boris (1998). Pravda o Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine: Sbornik statei. Izd-vo "Aleteiia". p. 2. ISBN 978-5893291025. http://militera.lib.ru/research/sokolov1/pre.html. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Jörg R. von Mettke (6 May 1985). "1945: Absturz ins Bodenlose [1945: Fall into the Abyss]" (in German). Der Spiegel. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13513054.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Svarzevich, Vladimir (9 November 2005). "Галина Джугашвили: "Мне до сих пор не хватает отца" [Galina Dzhugashvili: I Still Miss My Father]" (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. http://gazeta.aif.ru/online/aif/1306/63_01. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Alexander S. Birkos (1976). Soviet cinema: directors and films. Shoe String Press Inc.. ISBN 978-0208015815. page 86.

- ^ "День Победы у экрана [Victory Day on the Screen]" (in Russian). Komsomolskaya Pravda. 8 May 2008. http://www.kp.kg/daily/24095.3/323643/. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Andrei Plachov, Alexei Karakhan (4 August 2001). "Кровь в бутылке из-под колы [Blood in a Coca Cola Bottle]" (in Russian). kommersant.ru. http://www.kommersant.ru/Doc/277163/Print. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ ""Освобождение": хроника войны [Liberation: War Chronicle]" (in Russian). http://gazeta.gmedia.kz/pavlodar/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid=320. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Nine Lsovoi (February 2008). "Слово мастера [The Word of the Master]" (in Russian). Техника и технологии кино. http://ttk.625-net.ru/files/605/531/h_45eac6de29116a08d11cc932436d2759. Retrieved 15 April 2011.page 7.

- ^ Vitaly Abramov (7 May 2010). "Дмитрий Медведев: "Нам не надо стесняться рассказывать правду о войне" [Dmitry Medvedev: "We Should Not Hesitate to Tell the Truth About the War"]" (in Russian). Izvestia. http://www.izvestia.ru/pobeda/article3141617/. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "МНЕНИЯ И КОММЕНТАРИИ ЧЛЕНОВ СОВЕТА ФЕДЕРАЦИИ [Views of the Members of the Federative Council]" (in Russian). council.gov.ru. 7 May 2010. http://council.gov.ru/inf_ps/chronicle/2010/05/item12628.html. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Путин получит в подарок "Большую советскую энциклопедию" и киноэпопею "Освобождение" [Putin Would Receive the Great Soviet Encyclopedia and the Film Series Liberation]" (in Russian). KPU News Agency. 28 December 2010. http://kpunews.com/main_topic14_14493.html. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

Annotations

- ^ In the film, Tito converses with an English delegate (played by Voldemārs Akurāters) whom he calls 'Captain Stuart'. Captain William F. Stuart, a Canadian operative of the Special Operations Executive, arrived in Yugoslavia shortly before the battle and was killed during it.

- ^ The series treats Zhukov favourably. His failed idea to cross the Oder with searchlights is presented as brilliant, and his version on the events of the Berlin Offensive is accepted as true (After the war, Chuikov claimed that the Red Army should have rushed to Berlin in February 1945, before its defenses were strengthened. Zhukov was keen to do so at the time, yet Stalin ordered him to secure the northern flank by attacking Pomerania. Later, he denied this and stated that their forces were too overstretched for attacking the enemy's capital, presenting the delay as his own idea. see Kochukov, Aleksandr (20 April 2002). "Спор маршалов [The Marshals' Dispute]" (in Russian). Krasnaya Zvezda. http://www.redstar.ru/2002/04/20_04/5_01.html. Retrieved 19 December 2010.. In The Battle of Berlin, Stavka orders to take Berlin at once, and Zhukov defies it.)

External links

- The Fire Bulge, Breakthrough, Direction of the Main Blow part I and part II, The Battle of Berlin and The Last Assault on Mosfilm's official Youtube channel.

- The Fire Bulge, Breakthrough and Direction of the Main Blow, Battle of Berlin, The Last Storm for free viewing on the official site of the Mosfilm Studio.

- A 2005 television interview with Dilara Ozerova.

- A 2011 television interview with Dilara Ozerova.

- Stills related to Liberation on RIA Novosti's photographs archive.

- Liberation at the Internet Movie Database

- Liberation on Kino-Teatr.ru.

- Liberation on Melofanas.lt.

- Liberation on Filmportal.de.

- Liberation on Ostfilm.de.

Films directed by Yuri Ozerov 1950s Arena of the Bold (1953) · Son (1955) · Kochubey (1957) · High Road (1959)1970s Liberation (1970-1971) · Visions of Eight (1973) · Soldiers of Freedom1980s O Sport, You Are the World (1981) • Battle of Moscow (1985) • Stalingrad (1989)1990s Angels of Death (1993)Categories:- Soviet films

- Polish films

- Yugoslav films

- Italian films

- 1970 films

- 1971 films

- Soviet war films

- East German films

- Mosfilm films

- Avala Film films

- Russian-language films

- German-language films

- Eastern Front of World War II films

- War epic films

- Films directed by Yuri Ozerov

- Films shot in Poland

- Films shot in Germany

- Films shot in Russia

- Films shot in Rome

- Films shot in Moscow

- Films set in 1943

- Films set in 1944

- Films set in 1945

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in Moscow

- Films set in Ukraine

- Films about the German Resistance

- Films set in Poland

- Films set in Warsaw

- Films about the Soviet Union in the Stalin era

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.