- Maniac Mansion

-

This article is about the video game. For the television series, see Maniac Mansion (TV series).

Maniac Mansion

Ken Macklin's cover artwork depicts five of the playable characters: Syd, Dave, Bernard, Razor, and Jeff.Developer(s) Lucasfilm Games- Home computers

Lucasfilm Games

NES

LucasArts[1]

Realtime Associates[2]

Publisher(s) Lucasfilm Games- Home computers

Lucasfilm Games

NES

Jaleco

Designer(s) Ron Gilbert

Gary WinnickProgrammer(s) Ron Gilbert

David FoxArtist(s) Gary Winnick Composer(s) Chris Grigg

David LawrenceEngine SCUMM Platform(s) Commodore 64, Apple II, IBM PC, Amiga, Atari ST, Nintendo Entertainment System Release date(s) Genre(s) Graphic adventure Mode(s) Single-player Media/distribution Floppy disk, cartridge Maniac Mansion is a 1987 graphic adventure game developed and published by Lucasfilm Games. It was Lucasfilm's first published video game, and it was initially released for the Commodore 64 and Apple II. A comedy horror parody of B movies, it follows teenager Dave Miller as he ventures into a mansion and attempts to rescue his girlfriend from an evil mad scientist. The player uses a point-and-click control system to guide Dave and two of his friends through the mansion, avoiding its dangerous inhabitants and solving puzzles. The game was conceived in 1985 by Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, and the story was based on horror film and B movie clichés with humorous elements added in. The characters were based on people the developers knew as well as from characters from movies, comics, and horror magazines.

The game features a point-and-click interface, which was born out of the designers' desire to improve on contemporary text parser-based graphical adventure games seen in most Sierra Entertainment adventure titles. Gilbert implemented a game engine named SCUMM to reduce the effort required for the envisioned game. The engine and its accompanying scripting language have been later re-used for many other games. The game had to be reduced to 64 KB to fit within the Commodore 64's size limitations. The game was ported to several other platforms; its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) version had to be considerably modified to comply with Nintendo of America's policies to be more suitable for younger audiences.

Regarded as a seminal adventure title, Maniac Mansion received critical acclaim across all ports; reviewers lauded its graphics, cutscenes, animation, and humor. Its point-and-click interface has been regarded as revolutionary by reviewers and other developers, and has served as template for future Lucasfilm titles. The game influenced numerous other titles, has been placed on several "hall of fame" lists, and has received fan remakes with enhanced visuals. A TV series was created in 1990, which Eugene Levy created and which starred comedian Joe Flaherty as the mad scientist Dr. Fred; the series lasted for three seasons, filming 66 episodes. In 1993, a sequel, Day of the Tentacle, was released, also to critical acclaim.

Contents

Overview

Maniac Mansion takes place in the mansion of the Edison family: Dr. Fred, Nurse Edna, and their son Weird Ed.[3] Living with the Edisons are two large, disembodied tentacles – one purple and the other green.[4] The intro sequence shows that a meteor crashed near the mansion 20 years earlier.[3][5] The sentient meteor took control of the family and caused Dr. Fred to start sucking out human brains for use in experiments – something in which the rest of his family has supported and encouraged. One day, main protagonist Dave Miller's cheerleader girlfriend, Sandy Pantz, disappears without a trace, and he suspects that Dr. Fred has kidnapped her.[6] After the game's introduction, Dave and his two companions prepare to enter the mansion to rescue Sandy;[3][5] the game starts with a prompt for the player to select two of six characters to accompany Dave.[4]

Maniac Mansion is a graphic adventure game in which the player uses a point-and-click interface to guide characters through a two-dimensional (2D) game world and to solve puzzles.[3][7] Players can select among fifteen different commands with this scheme;[4][8] they include "Walk to", to move the characters; "New kid", to switch between the three characters; and "Pick up", to collect objects. Each character possesses unique abilities; for example, Syd and Razor can play musical instruments, while Bernard can repair appliances.[9] The game may be completed with any character combination, but, because many puzzles can be solved only with specific skills, there are different ways to finish the game, depending on the characters the player has chosen.[3][10]

The gameplay is regularly interrupted by cutscenes (a term coined by Ron Gilbert[11][12]) that advance the story and inform the player about non-player characters' actions.[3][4] Aside from the green tentacle, most of the mansion's inhabitants pose a threat and will throw the player characters into the dungeon – or, in some situations, kill them – if they see them. If one character dies, a replacement must be chosen from those that were not selected at the game's start; the game ends if all the characters die. Maniac Mansion has five possible successful endings, depending on which characters the player uses, which ones survive, and what they do.[13]

Development

Conception

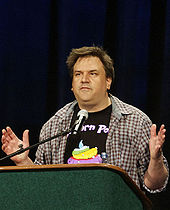

Ron Gilbert co-wrote and designed Maniac Mansion with Gary Winnick; both were puzzle and graphic adventure game fans.[14]

Ron Gilbert co-wrote and designed Maniac Mansion with Gary Winnick; both were puzzle and graphic adventure game fans.[14]

Maniac Mansion was first conceived in 1985, when Lucasfilm Games assigned employees Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick the task of creating an original game.[15] Gilbert had been recently hired at Lucasfilm Games by Noah Falstein on a three-month contract to program Koronis Rift, which Falstein was the lead developer. At the same time, Winnick was working on Labyrinth: The Computer Game, and it was then where both Gilbert and Winnick found that they shared similar tastes in humor, movies, and television programs. Eventually, Gilbert would he hired full-time. As with earlier Lucasfilm titles, the company's management provided little oversight in the development process, which Gilbert credited the success of many of their earlier games.[6]

Gilbert and Winnick were co-writers and lead designers of Maniac Mansion, but they worked separately on programming and art, respectively. Together, they brainstormed story ideas and, based on their love of B horror films, decided to create a comedy–horror title set in a haunted house.[15] Gilbert listed Re-Animator (1985) and The Fly (1986) as some of their favorite B horror films.[16] They drew inspiration on the game's main ideas over what Winnick said was "a ridiculous teen horror movie" they have watched, which the teens were in a house and got slaughtered one by one, not once thinking about leaving the house. They compared this film to clichés in other popular horror films such as Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street and used them to come up with the game's setting.[6] Early development involved experimentation and was organic in nature; according to Gilbert: "Very little was written down. Gary and I just talked and laughed a lot, and out it came." After development had begun, Lucasfilm Games relocated its office to the Stable House at Skywalker Ranch. The ranch's Main House inspired Winnick's design of the game's mansion, leading him to create the concept art for it.[7] He recreated several rooms in the Main House for the game, such as a library with a spiral staircase and a media room with a big screen TV and grand piano.[16] The other rooms in the mansion were inspired by the various rooms in the ranch.[6]

The pair prioritized the story and characters and wanted to maintain a balance between a "sense of peril and sense of humor".[14] The first character concepts were a set of siblings and their friends, which gradually evolved into the final characters.[16] Gilbert and Winnick based the characters both on stereotypes and people they knew; for example, Winnick's girlfriend Ray inspired Razor, and while Gilbert's mother apparently served as the basis for Nurse Edna,[7][16] Gilbert has denied the connection.[6] Dave and Wendy were based on Gilbert and a fellow employee named Wendy, respectively.[16] According to Winnick, the Edison family were based on various movie characters and elements from EC Comics and Warren Publishing magazines.[6] They sought to give each playable character unique abilities.[7] Several characters, however, had to be excluded due to size limitations.[15] To parody the horror genre, they inserted numerous clichés into the story,[7] drawing inspiration for several in-game elements from horror films. A segment of the 1982 anthology film Creepshow titled "The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill" was the inspiration for the meteor that takes control of Dr. Fred. The designers included a man-eating plant similar to the antagonist of the 1986 film Little Shop of Horrors.[16]

The pair struggled to choose a gameplay genre; Gilbert described their early ideas as "disconnected". While visiting relatives for Christmas, Gilbert saw his cousin playing King's Quest: Quest for the Crown. He was an adventure games fan and decided that the ideas he and Winnick had conceived would work well with the genre. Gilbert spent the holiday playing the game – which he called his first exposure to a text adventure with graphics – to familiarize himself with the format.[16]

Gilbert and Winnick created Maniac Mansion's basic structure and story prior to programming; its earliest version was a simple board game, which was playable on paper. The mansion's floor plan served as the game board, and cards represented events and characters.[7] Lines connected the rooms to illustrate pathways characters could travel. The designers used layers of cellulose acetate to map out the game's puzzles by tracking which items worked together when used by certain characters. Impressed with the complexity of their work, Winnick included the map in the game as a poster in one of the mansion's rooms.[16] Because each character contributed different skills and resources, they spent months working on the event combinations that could occur; this extended the game's production time beyond that of Lucasfilm Games' previous titles, which almost resulted in Gilbert's termination.[15] Though they had outlined the game's events, the dialog was not written until after programming had started;[7] the dialog would be provided by David Fox. Maniac Mansion would be one of the first games to feature alternate endings.[6]

Commodore 64 limitations

The Commodore 64 system's constraints forced the designers to adapt.

The Commodore 64 system's constraints forced the designers to adapt.

Development focused on the Commodore 64 platform. To accommodate the system, the staff tried to make the game small enough to fit into the computer's 64 KB memory.[15] They used scrolling to reveal objects and characters in rooms during cutscenes.[16] The designers also used the technique to force players to explore the mansion's larger rooms by hiding elements off screen.[11] However, generating the individual screens for the bitmap scrolling required 16 KB, which Gilbert considered too large. Instead, he used the computer's programmable character set to generate the game's visuals with limited memory, reducing the necessary file size per screen to around 1 KB. The set uses 8 × 8 pixel tiles. The computer, however, could only store 256 tiles, which limited the level of detail Winnick could design into the graphics. To circumvent this, Gilbert created a program to generate the tiles from Winnick's pixel art. To comply with the tile limit, the program compared similar tiles and created approximations that could replace multiple tiles. Winnick inspected the results for visual errors and then repeated the process. To make the characters easily recognizable, Winnick made the heads relatively large. Because sprites on the Commodore 64 were restricted to 24 pixels horizontally, the characters' animations never extend outside this width.[16]

SCUMM: game engine and scripting language

Main article: SCUMMGilbert started programming the game in assembly language for the 6502 microprocessor.[7][16] However, he soon determined that it would have taken him far too long to realize the ambitious game concept with this approach, and he concluded that he needed to build in support for some kind of abstract scripting language.[7][15] Initially, Gilbert considered basing this language on LISP, but ultimately chose a syntax that more closely resembles that of the C programming language.[16] He discussed the problem with fellow Lucasfilm employee Chip Morningstar, who helped him build a foundation for the game engine, which Gilbert then extended.[17] In designing the engine and language, Gilbert developed a "system that could be used on many adventure games, cutting down the time it took to make them". He logged considerable overtime with the goal of creating an adventure game superior to those of Lucasfilm's competitors.[15] Gilbert designed the engine to allow for multitasking so that designers could isolate and manipulate specific game objects independently.[16] Most of the first six to nine months of Maniac Mansion's development involved building the engine.[6]

All adventure games of the time required typing, and this is understandable given that most of them were text based. A few games, most notably the Sierra ones, had graphics but they still required typing. I never understood this and felt that it was only taking it halfway.

“”Ron Gilbert on the then-common input method in adventure games[15]A primary development goal was to create a control system that not only retained the structure of classic text adventures, but also dispensed with the typing.[15] The two lead designers were frustrated with the text parsers and the inevitable player character deaths that were prominent in the genre.[14] While in college, Gilbert had enjoyed Colossal Cave Adventure and Infocom's games but had "really wanted to see graphics".[16][17] He felt that the visual element Sierra Entertainment added for their games was "a big improvement", but he disliked the games' use of text parsers.[17] While playing Kings Quest, Gilbert found guessing what terms the designer had programmed it to recognize aggravating because he could see the object he wanted to interact with on the screen, but he was required to figure out the correct commands. Gilbert reasoned that if he could view the graphic, then he should be able to click on it with a cursor; by extension, the player should also be able to click on verb commands.[16] Gilbert devised a new and simpler interface "because I'm lazy and don't like to type. I hated playing adventure games where I had to type everything in, and I hated playing the 'second guess the parser' game so I figure everything should be point-and-click."[18]

The team originally envisioned 40 verb commands, but they whittled the number down to the 12 they felt were essential. The commands were then integrated into the scripting language in a similar fashion Sierra did with its Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI) and Sierra's Creative Interpreter (SCI).[16][19] Gilbert believed that a complex game did not require a text parser, but rather an innovative use of the interactions between in-game objects. He showed the team a demonstration of Sierra games and then led a discussion about their user interface and gameplay issues. Gilbert finished the engine – which he later named "Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion" (SCUMM) – after around a year of development. It freed the developers from having to code the details in low-level language.[7] Though the game had been designed with the Commodore 64 in mind, the SCUMM engine enabled Maniac Mansion to be easily ported to other platforms.[7][15] Lucasfilm developers Aric Wilmunder and Brad Taylor would assist in the PC port of the script.[6]

Scripting and testing

At Gilbert's request, David Fox, who had previously worked on Labyrinth: The Computer Game, assisted with Maniac Mansion's scripting. Fox was between projects and planned to do a month's work on the game; however, he stayed on the project for roughly six months.[7] He would discuss the game's events with Gilbert and Winnick, and use that information to create the rooms with the script.[16] The developers added designated areas or "walk-boxes" that characters could traverse.[11] Gilbert and Fox wrote the characters' dialog and choreographed the action. Fox expanded the game based on ideas he got from Winnick's concept art; for example, he allowed players to place a hamster in the kitchen microwave.[7] Dave Miller's original opening line of "Don't be a tuna head" was originally penned as "Don't be a shit head", but Lucasfilm Games forced them to remove the profanity.[6]

Gilbert wanted players to enjoy Maniac Mansion and not be punished for applying real world logic. In one adventure game, for example, the character could bleed to death by picking up a piece of glass. Fox asserted that "I know that in the real world I can successfully pick up a broken piece of mirror without dying" and characterized such game design as "sadistic". The team wanted to avoid illogical "surprise deaths" to spare players from having to regularly reload the game from a previous save state.[7] As a result, the group created a number of possibilities to give the player more freedom. While scripting the game, however, the designers realized that the number of characters resulted in a very complex game with a number of flaws, particularly dead ends that prevented the player from completing the game. To address these issues, they frequently revised the puzzles. In retrospect, Gilbert acknowledged that the fact that Lucasfilm Games had only one tester allowed many errors to go undetected.[16]

Release

In contrast to its previous games, where Lucasfilm Games had been only the developer and had used external publishers, the company started taking on the role of publisher with Maniac Mansion.[7] Lucasfilm Games hired Ken Macklin, whom Winnick knew, to design the packaging's artwork. Gilbert and Winnick collaborated with the marketing department to design the back cover. The two also created an insert that includes hints, backstory, and jokes.[16] Maniac Mansion would become the first title that Lucasfilm Games published.[20]

After around 18 to 24 months of development,[6] the game debuted at the 1987 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago.[21] The game was initially released for the Commodore 64 in October 1987.[22] After a Toys "R" Us customer complained about the word "lust" on the back cover, the toy store pulled the game from its shelves until Lucasfilm Games altered the box. Soon after the initial release, the Apple II port, with more detailed graphics and a larger display resolution, was released. Ports for the Atari ST, Amiga, Macintosh, and NES eventually followed.[16]

Nintendo Entertainment System version

Douglas Crockford (left) managed the conversion process for the game's Nintendo Entertainment System version, while Tim Schafer (right) play-tested the port.Published by Jaleco in September 1990,[23] Maniac Mansion was Lucasfilm Games' first NES release. The developer was unable to properly focus on the project due to a large workload, so Douglas Crockford volunteered to manage it. The studio used a modified version of the SCUMM engine titled "NES SCUMM" for the port.[1] Crockford commented that "one of the main differences between the NES and PCs is that the NES can do certain things much faster".[24] Developer Tim Schafer, who would go on to develop other Lucasfilm games, such as the sequel Day of the Tentacle, play-tested the port; this was Schafer's first professional credit.[25] The studio first changed the game's graphics to conform with the NES's display resolution and modified the content for a younger audience. Jaleco employee Howie Rubin advised Crockford as to what content Nintendo might object to. For example, the staff removed the word "kill" from the game at his suggestion. Reading the NES Game Standards Policy, however, led Crockford to believe that other elements might also conflict with the policy, so he sent a list of questionable content to Jaleco. Its staff believed that the content was reasonable, and Lucasfilm Games submitted Maniac Mansion to Nintendo.[1]

A month later, Nintendo of America sent Lucasfilm Games a report that outlined on-screen text it called offensive and nude graphics that it wanted removed. Crockford further modified the content to comply, while trying to maintain the game's essential aspects. For example, graffiti in a room provided players with hints on how to activate a story event. Unable to remove it, the designers shortened the message. Nintendo also listed objectionable dialog lines. Many of Nurse Edna's lines were originally sexually suggestive and had to be changed. Based on a phrase ("sucked out") that censors had deemed too graphic, the staff changed similar text on posters. The nudity Nintendo outlined encompassed a poster of a mummy in a playmate pose, a swimsuit calendar, and a classical statue of reclining woman. The studio removed the poster and calendar, but fought to keep the statue, claiming that it was modeled after a Michelangelo sculpture. The censors suggested an alteration, but Lucasfilm Games ultimately removed the object. Nintendo of America also objected to the phrase "NES SCUMM" in the end credits. Crockford removed the phrase, but questioned why the censors had overlooked more offensive content. In retrospect, Crockford felt that such standards resulted in "bland" products and called Nintendo a "jealous god".[1]

After implementing the changes, Lucasfilm Games re-submitted Maniac Mansion to Nintendo, which then manufactured 250,000 cartridges.[1][26] The NES cartridge features a battery back-up to save data,[27] and a prototype NES cartridge with the original content is rumored to exist.[27][28] In early 1990, Nintendo announced the port in its official magazine and provided further coverage later in the year.[9][29] The ability to microwave a hamster remained in the game, which Crockford cited as an example of the censors' confusing criteria.[1][27] However, Nintendo later noticed it, and had it removed from the European release.[15][27] After the initial batch of cartridges was sold, Nintendo made Jaleco remove the content in future releases.[26][27] The Japanese release omitted some graphical and musical elements, featured flip-screen scrolling, and had alterations to the characters' appearances.[6] Maniac Mansion was one of four games in the NES library – along with Shadowgate, F-15 Strike Eagle, and Déjà Vu – that were translated into Swedish.[30]

Reception

Reception Review scores Publication Score Eurogamer 9/10[31] ACE 820 out of 1000[8] Zzap!64 93%[4] The One Amiga 83%[32] Commodore User 8/10[33] Amiga Format 73%[34] The Games Machine 76%[35] Mean Machines 89%[36] Maniac Mansion was well received by critics. Several reviewers likened the game to films. Commodore User's Bill Scolding and Zzap!64's three reviewers – Paul Summer, Julian Rignall, and Steve Jarratt – compared it to The Rocky Horror Picture Show.[4][33] Other comparisons were drawn to Psycho, Friday 13th, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the Adams Family, and Scooby-Doo.[4][33][37] COMPUTE!'s Gazette's Keith Farrell cited its similarity to films, particularly with its use of cutscenes to add "information or urgency". He lauded its high level of detail along with its graphics and animation; Farrell wrote, "Each of the teenagers is fully realized, with features and wardrobe that are wholly in character."[38] Commodore Magazine's Russ Ceccola praised its cutscenes as innovative and high-quality. He called its ending "unforgettable" and praised the game's audiovisuals; he noted that the "characters are distinctively Lucasfilm's, bringing facial expressions and personality to each individual character". He ended by recommending readers to purchase Maniac Mansion, as it would please fans of the genre.[39]

Zzap!64's reviewers praised the game's humor and called its point-and-click control "tremendous"; they concluded by describing the game as "innovative and polished".[4] ACE magazine's reviewer enjoyed the game's animation, multi-character gameplay, and depth, and believed it to be "one of the better pics n' action games on the market". The reviewer enjoyed the game, but commented that "traditional adventurers" wouldn't as much.[8] Scolding noted its "flash graphics and black humour", and finished by calling the game one of the best of its kind.[33] German magazine Happy-Computer compared the cinematic cutscene usage to previous Lucasfilm titles Koronis Rift and Labyrinth: The Computer Game, and the menu system to ICOM Simulations' Uninvited. The reviewers highly lauded the game's user-friendly menu system, graphics, originality, and overall enjoyability; one of the reviewers called it the best adventure title at the time.[40] The magazine later reported that it was West Germany's highest-selling video game for three straight months.[41]

In more recent reviews, Eurogamer's Kristan Reed praised the game's "ambitious" design, citing the cast of characters, "elegant" interface, and writing.[31] Game designer Sheri Graner Ray listed Maniac Mansion as an example of a game that challenged the "damsel in distress" concept by including female protagonists.[42] Writer Mark Dery, however, commented that rescuing the kidnapped cheerleader was an example of an element that reinforced negative gender roles.[43] In choosing the top ten all-time games for the Commodore 64, Retro Gamer stated that Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken were equally good, but selected the latter because of Maniac Mansion's prominence.[44] In another issue, editor Ashley Day listed the game as having his favorite ending – the mansion's explosion upon pressing an unexpected button.[45] In 2009, IGN named Maniac Mansion the tenth best LucasArts adventure game.[46] Richard Cobbett of PC Gamer called it "one of the most intricate and important adventure games ever made", citing the SCUMM interface and establishing a legacy for Lucasfilm Games during this time.[47]

Reception of ports

Maniac Mansion was also well-received in multi-format reviews, including the Commodore 64, Apple II, and PC versions. Questbusters: The Adventurer's Newsletter editor Shay Addams called the game a parody of horror movies. He wrote that SCUMM worked better than the wheel used in Labyrinth: The Computer Game, calling it an improvement from Interplay's title Tass Times in Tonetown. Addams concluded by writing that Maniac Mansion was Lucasfilm's best title released and that it is a good buy for Commodore 64 and Apple II users who were unable to play games with better visuals such as from Sierra Entertainment.[37] Computer Gaming World's Charles Ardai praised the game's pacing, cutscenes, and humor, calling that it "strikes the necessary and precarious balance between laughs and suspense that so many comic horror films and novels lack". Despite faulting its small number of commands, he hailed its control system as "one of the most comfortable ever devised". However, Ardai disliked the game's small quantity of sound effects and music, and wondered why Lucasfilm had not hired John Williams to compose the score. Ardai finished by calling it "a clever and imaginative game[, ... and] a successful stylistic experiment".[5]

In other multi-format reviews, The Deseret News called it "wonderful fun" and noted that the "art and animation are gorgeous". The writers considered the game's audio to be "the best we've heard".[48] Reviewing the PC and Atari ST ports, a The Games Machine reviewer called Maniac Mansion "an enjoyable romp", with a structure superior to subsequent LucasArts adventure games. However, the magazine writer noted the game's poor pathfinding and stated that "the lack of sound effects reduces atmosphere". Of the two versions, the reviewer believed that the Atari ST audiovisuals were better.[35] Comparing the PC version to Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure, reviewers from French magazine Génération 4 praised the game's story, interface, and humor, stating that it was "beautifully done"; however, one reviewer commented that the graphics were ripped from Indiana Jones.[49] VideoGames & Computer Entertainment called Maniac Mansion "perhaps the most popular haunted-house adventure" and "a genuine cult classic with a large audience on both sides of the Atlantic"; while it found the plot and setup the same as most other horror-themed games, it praised the game's interface and execution.[50]

The game's Amiga version received a fair amount of praise, despite graphical shortcomings. In a 1993 review, The One Amiga's Simon Byron noted that the game retained its "charm and humour" six years after its first release. However, he believed that its art direction had become "tacky" compared to more recent games. Byron ended by writing that "if you fancy a cheap edge-of-the-seat challenge then you couldn't really do much better".[32] Amiga Format reviewer Stephen Bradly found the game derivative, but noted that it featured "loads of visual humour"; he added, "Strangely, it's quite compelling after a while."[34] German magazine Power Play wrote that the Amiga version "played like a poem" and just as well as the other ports.[51] Another German magazine, Amiga Joker, stated it was one of the best adventure games released for the computer, and while it wrote there were minor graphical flaws, such as a lack of variety in colors, it stated that the gameplay made up for those shortcomings.[52] Sweden-based Datormagazin's Ingela Palmér stated that the Amiga version differed little from the Commodore 64 one, and that those who already have the latter need not get the Amiga version. She added that, while the graphics and gameplay were not the best, the game remained highly enjoyable and easy. Palmér recommended that people new to the genre play this game first.[53]

Reviewers well-received Maniac Mansion's NES version. Based on the computer release's success, Game Players' writers speculated that the NES port would be one of 1990's better titles.[28] UK-based Mean Machines lauded the game for its presentation, playability, and replay value, while it criticized the blocky graphics and "ear-bashing tunes". Reviewer Edward Laurence wrote that little from the NES version had changed from the Commodore 64 version except for minor graphical and sound improvements. Julian Rignall compared the game to Shadowgate, but noted differences between the two; he commented how Maniac Mansion had easy controls and that it lacked Shadowgate's "death-without-warning situations". Despite his criticism of the audiovisuals, he wrote, "Maniac Mansion's excellent, thoroughly rewarding and genuinely funny gameplay more than makes up for its deficiencies, and the end result is a highly original and very addictive adventure that no Nintendo owner should be without."[36] Video Games magazine reviewed the translated German version, and the reviewers labeled the game as a "Video Games Classic". Co-reviewer Heinrich Lenhardt stated that Maniac Mansion was unique, and that no similar NES adventure game has since been released. He wrote that it was just as fun as the computer versions with good controls, but noted that the graphics could be misleading at times. Co-reviewer Winnie Forster wrote that the game was "one of the most original representatives of the [adventure game] genre" and that it has been one of Lucasfilm's more successful games.[54] In recent commentary, Edge magazine staff described the port as more conservative than the original version, calling it "somewhat neutered".[7] GamesTM magazine writers referred to the NES version as "infamous" and heavily censored.[15]

Maniac Mansion was featured frequently in the magazine Nintendo Power. The game debuted on the magazine's Top 30 list at number 19 in February 1991, peaking at number 16 in August 1991.[55][56] The magazine reviewed it again in its February 1993 issue, as part of an NES games overview, that the staff felt were overlooked or otherwise undersold. The editors felt that its September 1990 feature had been overshadowed at the time by the popular RPG Final Fantasy, drawing more people to that game instead.[57] Seven years after its release, in its 100th issue in September 1997, the magazine ranked the NES version the 61st best game, calling it a "brilliant adventure".[58] In its 20th anniversary issue, the magazine listed Maniac Mansion as the 16th best NES title, praising the game for its clever and funny writing and for being unlike any other game on the system.[59] In its November 2010 issue, in celebration of the NES' 25th anniversary, the game was described as "unlike anything else out there – a point-and-click adventure with an awesome sense of humor and multiple solutions to almost every puzzle."[60] Nintendo Power also commented on the ability to microwave a hamster;[58] in its 25th anniversary retrospective, the staff stated that "it's hard to mention Maniac Mansion without it".[60]

Impact and legacy

Referring to Maniac Mansion as a "seminal" title, GamesTM staff credited it with reinventing the graphical adventures' gameplay. The writer stated that not having to guess input verbs allowed players to focus more on the story and puzzles, resulting in less frustration and more enjoyment.[15] Reed made similar comments, writing that the design freed players from the "guessing-game frustration", and made "the whole process infinitely more elegant and intuitive."[31] Connie Veugen and Felipe Quérette noted, however, that the determining the game's vocabulary was an enjoyable aspect of the genre.[61] GamesTM magazine further commented that Maniac Mansion had solidified Lucasfilm Games as a leader in the graphic adventure genre.[15] Authors Mike and Sandie Morrison commented that the studio had brought "serious competition" to the graphic adventure genre in the form of Maniac Mansion.[62] Authors Rusel DeMaria and Johnny Wilson echoed their sentiments, calling it a "landmark title" for the company. They also stated that the game, along with Space Quest and Leisure Suit Larry, had inaugurated a "new era of humor-based adventure games".[63] Reed seconded the statement, stating that the game "set in motion a captivating chapter in the history of gaming" that encompassed wit, invention, and style.[31] GameSpy's Christopher Buecheler credited the game's success with making its genre commercially and critically viable.[12] It was also one of the first video games to feature product placement, as the game featured Pepsi brands; other games, such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Arcade Game (featuring Pizza Hut), Zool (featuring Chupa Chups), and Tapper (featuring Budweiser), followed suit.[64] Retro Gamer's Stuart Hunt said in a September 2011 issue that "Maniac Mansion proved that videogames could capture the essence of an entirely different medium and opened our eyes to the wonderful things that happened when they placed their interactive stamp on them". The Secret of Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle developer Dave Grossman said that Maniac Mansion revolutionized the adventure game genre, also noting the fact that the game was only 64 KB large and that the music was good, especially for PCs.[6]

Reed described SCUMM as "revolutionary".[31] Lucasfilm Games used the SCUMM engine to develop eleven other games in the following decade, and competitors eventually adopted similar systems; GamesTM attributed this change to a desire to streamline production and produce fun games.[15] The developers improved the engine with each subsequent game.[16] Following his departure from LucasArts (Lucasfilm Games had been combined under this name with ILM and Skywalker Sound in 1990[65]) in 1992, Gilbert used the SCUMM technology to create adventure games and Backyard Sports games at Humongous Entertainment.[16] The designers built on their experience developing Maniac Mansion and expanded the process and their ambition in subsequent titles.[14] In retrospect, Gilbert commented that he made a number of mistakes in designing Maniac Mansion (for instance, the dead-end situations that arise if certain items are used incorrectly) and applied the lessons to future games. In cut scenes, Gilbert had used a timer rather than a specific event to trigger the scene, which occasionally resulted in awkward scene changes. The designer aimed to avoid these flaws in the Monkey Island series of games.[15] Gilbert, however, has commented that Maniac Mansion is his favorite because of its imperfections.[16]

In popular culture

Elements of Maniac Mansion have appeared elsewhere in popular culture, especially in other Lucasfilm games. An in-game object called "Chuck the Plant" reappeared in other Lucas adventure titles like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and Tales of Monkey Island.[66][67] According to Gilbert, Steve Arnold, the LucasFilm general manager at the time, had a long running joke in which he continually requested game designers to add a character named Chuck to their game. Gilbert and Winnick were the first to humor Steve's request in Maniac Mansion. Because there was no room for an additional character name in the game, the name was given to the plant.[68] In the game's NES version, a broken record is titled The Soundtrack Of Loom, in reference to another Lucasfilm video game Loom.[69] David Fox included a gasoline item for a nonexistent chainsaw in his game Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders as a parody of the chainsaw that required nonexistent gasoline in Maniac Mansion. Enthusiasts have created fan art depicting the characters, participated in cosplay based on the tentacle characters, and produced a trailer of a fictitious live action film.[16]

Various fanmade enhanced remakes of Maniac Mansion have appeared over the years. One German fan, Sascha Borisow, created a remake titled Maniac Mansion Deluxe with enhanced audio and visuals. He used Adventure Game Studio freeware to develop the game, and distributed it free on the internet.[70][71] The remake had been downloaded over 200,000 times by the end of 2004.[72] German developer Vampyr Games created a remake with 3D computer graphics titled Meteor Mess 3D, which began as a learning tool for Gamestudio.[73][74] A group of German gamers called Edison Interactive is developing another remake, titled Night of the Meteor, which combines Maniac Mansion's features with Day of the Tentacle's graphics.[75] Fans also created an episodic series of games based on Maniac Mansion.[76] An uncensored unofficial NES version is also known to exist on Frank Cifaldi's website LostLevels.org.[77] Gilbert stated that he would like to see an official remake resemble the gameplay and graphics from Tales of Monkey Island, but he balked, citing George Lucas' enhanced remakes of the original Star Wars trilogy as a reason to keep the flaws in the original game.[78]

TV adaptation and game sequel

Main articles: Maniac Mansion (TV series) and Day of the TentacleLucasfilm had conceived the idea for a television adaptation, which The Family Channel purchased in 1990.[79] A sitcom named after the game debuted in September 1990.[80] It aired on YTV in Canada and The Family Channel in the United States.[81] Partially based on the video game, the show, focused on the Edison family's life, featured Joe Flaherty as Dr. Fred. Eugene Levy headed the writing staff. The program was a collaboration between Lucasfilm, The Family Channel, and Atlantis Films.[82] In retrospect, Gilbert commented that the premise gradually changed during production to something that differed greatly from the game's original plot.[16] Upon its debut, the show was well-received by critics;[83][84][85] Time magazine named it one of the best new shows of the year.[86] However, other reviewers, such as Entertainment Weekly's Ken Tucker, questioned how the show made it on The Family Channel, given Flaherty's usage of SCTV-like humor.[84] PC Gamer's Richard Cobbett, in a retrospective on the series, criticized its lack of relevance to the game and generic storylines.[47] The series lasted for three seasons, filming 66 episodes.[6]

In the early 1990s, LucasArts asked Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer, who had both worked with Gilbert on the Monkey Island games, to design a sequel to Maniac Mansion. Winnick and Gilbert initially assisted with the writing. Grossman and Schafer were able to include the voices and the improved visuals Gilbert had originally envisioned for Maniac Mansion. Day of the Tentacle, as the sequel came to be called, discarded the character selection and branching story lines in favor of a simpler format, and introduced time travel as the main puzzle element. The game retained the Edison family and Bernard characters, but changed the art style to be reminiscent of Chuck Jones' works. As a homage to Maniac Mansion, the designers included a puzzle that involves freezing a hamster;[87] according to Grossman, he gave a happier outcome for the hamster as a response to Gilbert's grim ending for the hamster in Maniac Mansion.[88] They also made the full original game playable on an in-game computer,[15] which Grossman attributed to a software bug.[87] LucasArts released Day of the Tentacle in 1993 to critical acclaim.[15][89]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "The Expurgation of Maniac Mansion". Douglas Crockford. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071012031110/http://www.crockford.com/wrrrld/maniac.html.

- ^ "Past Projects: Maniac Mansion". Realtime Associates, Inc.. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5v4g3nyYN.

- ^ a b c d e f Laurel, Brenda (1987). Maniac Mansion manual. San Rafael, CA: Lucasfilm Games.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Summer, Paul; Rignall, Julian; Jarratt, Steve (December 1987). "Maniac Mansion". Zzap!64 (Ludlow: Newsfield Publications) (32): 12–13. ISSN 0954-867X. OCLC 470391346.

- ^ a b c Ardai, Charles (May 1988). "The Doctor is in: An Appointment with Terror in Activision's Maniac Mansion". Computer Gaming World (Anaheim, CA: Golden Empire Publications) (47): 40–41. ISSN 0744-6667. OCLC 8482876.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hunt, Stuart (September 2011). "The Making Of Maniac Mansion". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (94): 24–33. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "The Making Of: Maniac Mansion". Edge (Bath, Somerset: Future Publishing) (151). July 2005. ISSN 1350-1593. OCLC 77560936. http://www.next-gen.biz/features/making-maniac-mansion. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c The Pilgrim (November 1987). "Maniac Mansion". ACE (Bath, Somerset: Future Publishing) (2): 89.

- ^ a b "Previews: Maniac Mansion". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (14): 62–63. July–August 1990. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ "Maniac Mansion". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (16): 14–19. September–October 1990. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ a b c Gilbert, Ron (April 12, 2007). "Maniac Mansion in 9". Grumpy Gamer. http://grumpygamer.com/8139425. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Buecheler, Christopher. "The Gamespy Hall of Fame: Maniac Mansion". GameSpy. http://archive.gamespy.com/legacy/halloffame/mm.shtm. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Addams, Shay (December 1987). "Animated Adventuring in Maniac Mansion". Commodore Magazine (West Chester, PA) 8 (12): 48, 110.

- ^ a b c d LucasArts (1992). "Introduction". LucasArts Classic Adventures. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Behind the Scenes: Maniac Mansion + Day of the Tentacle". GamesTM. The Ultimate Retro Companion (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (3): 22–27. 2010. ISSN 1448-2606. OCLC 173412381.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Gilbert, Ron (March 4, 2011). "Classic Game Postmortem: Maniac Mansion" (Flash Video). Game Developers Conference. http://www.gdcvault.com/play/1014732/Classic-Game-Postmortem-MANIAC. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c Hatfield, Daemon (April 26, 2007). "Interview: SCUMM of the Earth". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/articles/783/783847p1.html. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Wild, Kim (July 20, 2006). "Developer Lookback – LucasArts – Part One". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (27): 32–39. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). Vintage Games. Burlington, MA: Focal Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-240-81146-8.

- ^ "The Complete History of Star Wars Videogames – Episode II". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (53): 56. July 2008. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith (August 1987). "CES and COMDEX: A Tale Of Two Cities". COMPUTE!'s Gazette (New York City: General Media) (87): 14. ISSN 0737-3716. OCLC 649175217.

- ^ "20th Anniversary". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Archived from the original on June 24, 2003. http://web.archive.org/web/20030624215636/www.lucasarts.com/20th/history_1.htm.

- ^ "Classic Games List". Nintendo of America, Inc.. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5v4hIOvNU.

- ^ "NES Journal". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (14): 88. July–August 1990. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ "In the Chair with Tim Schafer". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (22): 40. March 2, 2006. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ a b Kent, Steven (2001). "The New Empire". Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, CA: Prima Publishing. pp. 365–366. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ^ a b c d e Santulli, Joe (2002). Digital Press Video Game Collector's Guide (7 ed.). Pompton Lakes, NJ: Digital Press. ISBN 978-0-9709807-0-0.

- ^ a b "Maniac Mansion". Game Player's Strategy Guide to Nintendo Games (Greensboro, NC: Signal Research, Inc.) 3 (2): 6, 10. 1990. ISSN 1042-3133. OCLC 34042091.

- ^ "Gossip Galore". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (11): 93. March–April 1990. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ Kilpeläinen, Jyri (June 12, 2011). "Top 5 Scandinavian exclusive console games". Polarcade. http://www.polarcade.com/2011/06/12/top-5-scandinavian-exclusive-console-games/. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Reed, Kristan (October 26, 2007). "Maniac Mansion Review". Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/maniac-mansion-review. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Byron, Simon (June 1993). "Cheapos!". The One Amiga (Peterborough: EMAP) (57): 90. ISSN 0962-2896. OCLC 225907628.

- ^ a b c d Scolding, Bill (December 1987). "Maniac Mansion". Commodore User (Peterborough: EMAP) (51): 42. ISSN 0265-721X. OCLC 124015983.

- ^ a b Bradly, Stephen (August 1993). "Budget Reviews". Amiga Format (Bath, Somerset: Future Publishing) (49): 96. ISSN 0957-4867. OCLC 225912747.

- ^ a b "Maniac Mansion". The Games Machine (Ludlow: Newsfield Publications) (25): 67. December 1989. ISSN 0954-8092. OCLC 500096266.

- ^ a b Rignall, Julian; Laurence, Edward (December 1991). "Maniac Mansion review – Nintendo Entertainment System" (pdf). Mean Machines (Peterborough: EMAP) (15): 67–68. ISSN 0960-4952. OCLC 500020318. http://www.meanmachinesmag.co.uk/pdf/maniacmansionnes.pdf. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Addams, Shay (August 1987). "Maniac Mansion". Questbusters: The Adventurer's Newsletter (Wayne, PA: Addams Expedition): 3, 9.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith (November 1987). "Maniac Mansion". COMPUTE!'s Gazette (New York City: General Media) (53): 35–36. ISSN 0737-3716. OCLC 649175217.

- ^ Ceccola, Russ (March 1988). "Maniac Mansion". Commodore Magazine (West Chester, PA): 22–23. ISSN 0814-5741. OCLC 216544886.

- ^ Schneider, Boris; Lenhardt, Heinrich (April 1986). "Maniac Mansion" (in German). Happy-Computer. http://www.kultpower.de/powerplay_datenbank.php3?game_id=605. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ "German gamers pick Maniac". VideoGames & Computer Entertainment (Beverly Hills, CA: Larry Flynt Publications) (4): 14. May 1989. ISSN 1059-2938. OCLC 25300986.

- ^ Graner Ray, Sheri (2003). Gender Inclusive Game Design: Expanding the Market. Hingham, MA: Charles River Media. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-58450-239-5.

- ^ Déry, Mark (1994). "Anne Balsamo". Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8223-1540-7.

- ^ "Commodore 64 – Perfect Ten Games". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (30): 25. October 12, 2006. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Day, Ashley (July 20, 2006). "Retrobates – Favourite Game Ending". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (27): 3. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "Top 10 LucasArts Adventure Games". IGN. November 17, 2009. http://pc.ign.com/articles/104/1046144p1.html. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Cobbett, Richard (July 23, 2011). "Saturday Crapshoot – Maniac Mansion (TV)". PC Gamer. http://www.pcgamer.com/2011/07/23/saturday-crapshoot-maniac-mansion-tv/. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Peterson, Franklynn; K-Turkel, Judi (April 30, 1989). "We Had to Reconsider Bombing Platoon Game; Maniac Mansion, Dive Bomber are Good Fun, Too". The Deseret News. http://www.deseretnews.com/article/44671/WE-HAD-TO-RECONSIDER-BOMBING-PLATOON-GAME-MANIAC-MANSION-DIVE-BOMBER-ARE-GOOD-FUN-TOO.html. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "Maniac Mansion" (in French). Génération 4 (16): 70, 72. November 1989.

- ^ Kunkel, Bill; Worley, Joyce (September 1989). "Spooky Software". VideoGames & Computer Entertainment (Beverly Hills, CA: Larry Flynt Publications) (10): 62. ISSN 1059-2938. OCLC 25300986.

- ^ Lenhardt, Heinrich (March 1990). "Maniac Mansion" (in German). Power Play 1990 (3). http://www.kultpower.de/powerplay_datenbank.php3?game_id=1212. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ Labiner, Michael (February 1990). "Maniac Mansion" (in German). Amiga Joker 1990 (2). http://www.kultpower.de/external_frameset.php3?site=amigajoker_testbericht.php3%3Fim%3Dmaniacmansion.jpg%26backurl%3Dindex_main2.php3. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ Palmér, Ingela (March 1990). "Alla har ett fånigt flin – Maniac Mansion (Lucasfilm)" (in Swedish). Datormagazin 1990 (6): 29.

- ^ Forster, Winnie; Lenhardt, Heinrich (June 1991). "Gehirne, Gags & Gänsehaut – Maniac Mansion" (in German). Video Games 2 (6): 38–39. http://www.kultpower.de/external_frameset.php3?site=videogames_testbericht.php3?im=maniacmansion.jpg. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ "Nintendo Power Top 30". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (21). February 1991. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ "Nintendo Power Top 30". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (27). August 1991. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ "The Unsung Heroes of the NES". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (45): 43. February 1993. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ a b "100 Best Games of All Time". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (100): 96. September 1997. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ "Nintendo Power – The 20th Anniversary Issue!". Nintendo Power (San Francisco, California: Future US) (231): 71. August 2008. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Chris (November 2010). "Maniac Mansion". Nintendo Power (San Francisco, CA: Future US) (260): 55. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ Veugen, Connie; Quérette, Felipe (2008). "Thinking out of the box (and back in the plane)". Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture (Cambridge, MA: Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab) 2 (2): 215–239. ISSN 1866-6124. http://journals.sfu.ca/eludamos/index.php/eludamos/article/view/vol2no2-6/86. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ Morrison, Mike; Morrison, Sandie. "The History of Interactive Entertainment". The Magic of Interactive Entertainment. Indianapolis, IN: SAMS Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-672-30590-0.

- ^ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny (2003). High score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2 ed.). New York City: McGraw-Hill. pp. 140, 200. ISBN 978-0-07-223172-4.

- ^ Per Anre Sandvik (April 2005). "Strange Games". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (15): 86. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "A Short History of LucasArts". Edge Online. August 28, 2006. http://www.next-gen.biz/features/short-history-lucasarts. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon; Smith, Jonas; Tosca, Susana (2008). "History". Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. London: Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-97721-0.

- ^ "Tales of Monkey Island – Chapter 1: Launch of the Screaming Narwhal Walkthrough". GameSpy. January 2, 2009. http://pc.gamespy.com/pc/tales-of-monkey-island/guide/page_6.html. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Gilbert, Ron (May 2, 2007). "20 Years of SCUMM". Ron Gilbert (The Grumpy Gamer). http://grumpygamer.com/2905697#comment. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Wild, Kim (January 3, 2008). "The Making Of ... Loom". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (46): 88. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "101 Free Games 2007 – The Best Free Games on the Web!". Games for Windows: the Official Magazine (New York City: Ziff Davis) (3): 8. February 2007. ISSN 1933-6160. OCLC 71652861. http://www.1up.com/features/101-free-games_2. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Ogles, Jacob (December 23, 2004). "Maniacs Make a Modern Mansion". Wired.com. http://www.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/news/2004/12/66109. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Gilbert, Ron (October 19, 2004). "The Economics of a 2D Adventure in Today's Market". Grumpy Gamer. http://grumpygamer.com/4904226. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Caoili, Eric (November 24, 2009). "Maniac Mansion 3D Remake 'Nearly Complete'". GameSetWatch. http://www.gamesetwatch.com/2009/11/maniac_mansion_3d_remake_nearl.php. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Rudden, Dave (February 2, 2010). "German developers remaking Maniac Mansion as Meteor Mess 3D". GamePro. http://www.gamepro.com/article/news/213830/german-developers-remaking-maniac-mansion-as-meteor-mess-3d/. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (May 26, 2011). "Holy Shit, Somebody is Remaking Maniac Mansion". Kotaku. http://kotaku.com/5805767/holy-shit-somebody-is-remaking-maniac-mansion. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ Gladstone, Darren; Sharkey, Scott (January 14, 2008). "101 Free Games 2008". 1UP.com. http://www.1up.com/do/feature?pager.offset=1&cId=3165201. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ "Retroinspection – NES". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (38): 62. May 24, 2007. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Dutton, Fred (March 4, 2011). "Gilbert would "love" new Maniac Mansion". Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2011-03-04-gilbert-would-love-new-maniac-mansion. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Svetkey, Benjamin (January 17, 1992). "A Short Visit to Maniac Mansion". Entertainment Weekly (New York City: Time Inc.) (101). ISSN 1049-0434. OCLC 21114137. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,309225,00.html. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Harris, J. P. (2002). Time Capsule: Reviews of Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Films and TV Shows from 1987-1991. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-595-21336-8.

- ^ McRoberts, Kenneth (1995). Beyond Quebec: Taking Stock of Canada. Montreal, Quebec/Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7735-1314-3.

- ^ "On the Air". Nintendo Power (Redmond, WA: Nintendo) (16): 89. September–October 1990. ISSN 1041-9551. OCLC 18893582.

- ^ Prouty (1994). Variety TV Reviews 1991-92. 17. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8240-3796-3.

- ^ a b Tucker, Ken (October 5, 1990). "TV Review: Maniac Mansion". Entertainment Weekly (New York City: Time Inc.) (34). http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,20193670,00.html. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Howard (September 14, 1990). "The New Season: Demented Experiment in Maniac Mansion". Los Angeles Times (Tribune Company). http://articles.latimes.com/1990-09-14/entertainment/ca-73_1_maniac-mansion. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ "Best of '90: TV". Time (New York City: Time Inc.) 136 (28). December 31, 1990. ISSN 0040-781X. OCLC 1767509. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,972059,00.html. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Wild, Kim (September 2010). "The Making Of Day Of The Tentacle". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (81): 84–87. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Wild, Kim (August 17, 2006). "Developer Lookback – LucasArts – Part Two". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (28): 20–25. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle for PC". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/game/pc/maniac-mansion-day-of-the-tentacle. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

External links

LucasArts adventure games Indiana Jones series Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) · Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (1992)

Maniac Mansion series Maniac Mansion (1987) · Day of the Tentacle (1993) · Maniac Mansion TV series

Monkey Island series The Secret of Monkey Island (1990) · Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge (1991) · The Curse of Monkey Island (1997) · Escape from Monkey Island (2000)

Independent titles Labyrinth (1986) · Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders (1988) · Loom (1990) · Full Throttle (1995) · The Dig (1995) · Sam & Max Hit the Road (1993) · Grim Fandango (1998)

Cancelled projects Full Throttle: Payback · Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels · Sam & Max: Freelance Police

People Technology Categories:- 1987 video games

- Adventure games

- Amiga games

- Apple II games

- Atari ST games

- Comedy video games

- Commodore 64 games

- DOS games

- Jaleco games

- LucasArts games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Parody video games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- Realtime Associates games

- Horror video games

- ScummVM supported games

- SCUMM games

- Home computers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.