- Mary of Modena

-

"Mary of Modena" redirects here. For the wife of Ranuccio II Farnese, Duke of Parma, see Maria d'Este.

Mary of Modena Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland Tenure 6 February 1685 – 11 December 1688 (3 years, 309 days) Coronation 23 April 1685 (aged 26) Spouse James II Issue James Francis Edward Stuart

Louisa Maria Teresa StuartFull name Italian: Maria Beatrice Anna Margherita Isabella d'Este House House of Este

House of StuartFather Alfonso IV, Duke of Modena Mother Laura Martinozzi Born 5 October 1658

Ducal Palace, Modena, ModenaDied 7 May 1718 (aged 59)

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Paris, FranceBurial Convent of the Visitations, Chaillot, France Mary of Modena (Maria Beatrice Anna Margherita Isabella d'Este;[1] 5 October [O.S. 25 September] 1658 – 7 May [O.S. 26 April] 1718) was Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the second wife of King James II and VII. A devout Catholic, Mary became, in 1673, the second wife of James, Duke of York, who later succeeded his older brother Charles II as King James II.[2][3] Mary was uninterested in politics and devoted to James and her children, two of whom survived to adulthood: the Jacobite claimant to the English, Scottish and Irish thrones, James Francis Edward Stuart, known as "The Old Pretender", and Princess Louise Mary.[4]

Born a princess of the Italian Duchy of Modena, Mary is primarily remembered for the controversial birth of James Francis Edward, her only surviving son. The majority of the English public believed he was a changeling, brought into the birth-chamber in a warming-pan, in order to perpetuate King James II's Catholic dynasty. Although the accusation was entirely false, and the subsequent privy council investigation only reaffirmed this, James Francis Edward's birth was a contributing factor to the Glorious Revolution. The revolution deposed James II and replaced him with his daughter from his first marriage Mary and her husband, William III of Orange.

Exiled to France, the "Queen over the water"—as Jacobites (followers of James II) called Mary—lived with her husband and children in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, provided by Louis XIV of France. Mary was popular among Louis XIV's courtiers; however, James was considered a bore. In widowhood, Mary spent much time with the nuns at the Convent of Chaillot, where she and her daughter spent their summers. In 1701, when James II died, James Francis Edward became king in the eyes of Jacobites, as "James III". As he was too young to assume the nominal reins of government, Mary acted as regent until he reached the age of 16. When "James III" was asked to leave France as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, Mary stayed, despite having no family there, Princess Louise Mary having died of smallpox. Fondly remembered by her French contemporaries, Mary died of breast cancer in 1718.

Contents

Early life (1658–1673)

Alfonso IV d'Este, Duke of Modena, Mary's father, in a portrait by Justus Sustermans.

Alfonso IV d'Este, Duke of Modena, Mary's father, in a portrait by Justus Sustermans.

Mary Beatrice d'Este, the elder child of Alfonso IV, Duke of Modena, and his wife, Laura Martinozzi, was born on 5 October 1658 NS[note 1] in Modena, Duchy of Modena, Italy.[3] Her only sibling, Francesco, succeeded their father as Duke upon his death in 1662, the year Mary turned four.[5] Mary and Francesco's mother Laura was strict with them, and acted as regent of the duchy until her son came of age.[6][7] Mary's education was excellent;[8] she spoke French and Italian fluently, had a good knowledge of Latin and, later, mastered English.[9][10]

Mary was described by contemporaries as "tall and admirably shaped", and sought as a bride for James, Duke of York, by Lord Peterborough.[11][12] Lord Peterborough was groom of the stole to the Duke of York. A widower, James was the younger brother and heir of Charles II of England.[13] Duchess Laura was not initially forthcoming with a reply to Peterborough's proposal, hoping, according to the French ambassador, for a "grander" match with the eleven-year-old Charles II of Spain.[14][15] Whatever the reason for Laura's initial reluctance, she finally accepted the proposal on behalf of Mary, and they were married by proxy on 30 September 1673 NS.[16]

Modena was within the sphere of influence of Louis XIV of France, who endorsed Mary's candidature and greeted Mary warmly in Paris, where she stopped en route to England, giving her a brooch worth £8,000.[17][note 2] Her reception in England was much cooler.[19] Parliament, which was entirely composed of Protestants, reacted poorly to the news of a Catholic marriage, fearing it was a "Papist" plot against the country.[19] The English public, who were predominantly Protestant, branded the Duchess of York — as Mary was thereafter known as until her husband's accession — the "Pope's daughter".[20] Parliament threatened to have the marriage annulled,[20] leading Charles to suspend parliament until 7 January 1674 OS, to ensure the marriage would be honoured and safeguarding the reputation of his House of Stuart.[13]

Duchess of York (1673–1685)

Household

The Duke of York, an avowed Catholic, was twenty-five years older than his bride, scarred by smallpox and afflicted with a stutter.[21] He had secretly converted to Catholicism around 1668.[22] Mary first saw her husband on 23 November 1673 OS, on the day of their second marriage ceremony.[23][24] James was pleased with his bride.[25] Mary, however, at first disliked him, and burst into tears each time she saw him.[26] Nonetheless, she soon warmed to James.[4] From his first marriage to the commoner Anne Hyde, who had died in 1671, James had two daughters: Lady Mary and Lady Anne.[27] They were introduced to Mary by James with the words, "I have brought you a new play-fellow".[27] Unlike Lady Mary, Lady Anne disliked her father's new wife.[28] Mary played games with Anne, to win her affection.[28]

The Duchess of York annually received £5,000 spending money and her own household, headed by Carey Fraser, Countess of Peterborough; it was frequented by ladies of her husband's selection: Frances Stewart, Duchess of Richmond—Charles II's discarded mistress—and Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch.[13][29][30][31] That the Duchess of York loathed gambling did not stop her ladies compelling her to do so almost every day.[32] They believed that "if she refrained, it might be taken ill".[32] Consequently, Mary incurred minor gambling debts.[32]

The birth of the Duchess of York's first child, Catherine Laura, named after Queen Catherine, on 10 January 1675 OS represented the beginning of a string of children that would die in infancy.[33] At this time she was on excellent terms with Lady Mary and she visited her in The Hague after the younger Mary had married William of Orange. She travelled incognito and took Anne with her.[34]

Popish plot and exile

Main article: Popish plotThe Duchess of York's Catholic secretary, Edward Colman, was, in 1678, falsely implicated in a fictitious plot against the King by Dr. Titus Oates.[35] The plot, known as the Popish Plot, lead to the Exclusionist movement, which was headed by Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.[36] The Exclusionists sought to debar the Catholic Duke of York from the throne.[37] Their reputation in tatters, the Yorks were begrudgingly exiled to Brussels, a domain of the King of Spain, ostensibly to visit Lady Mary—since 1677 the wife of Prince William III of Orange.[38][39][40] Accompanied by her not yet three-year-old daughter Isabella and Lady Anne, the Duchess of York was saddened by James's extra-marital affair with Catherine Sedley.[41] Mary's spirits were briefly revived by a visit from her mother, who was living in Rome.[42]

Mary of Modena in the year of her husband's accession, 1685. Painting after Willem Wissing.

Mary of Modena in the year of her husband's accession, 1685. Painting after Willem Wissing.

A report that King Charles was very sick sent the Yorks back to England post-haste.[43] They feared the King's eldest illegitimate son, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, and commander of England's armed forces, might usurp the crown if Charles died in their absence.[43][44] The matter was compounded by the fact that Monmouth enjoyed the support of the Exclusionists, who held a majority in the House of Commons of England.[43] Charles survived but, feeling the Yorks returned to court too soon, sent James and Mary to Edinburgh, where they stayed on-and-off for the next three years.[45][46] Lodging in the dilapidated Holyrood Palace, the Yorks had to make do without Ladies Anne and Isabella, who stayed in London on Charles's orders.[47] The Yorks were recalled to London in February 1680, only to return again to Edinburgh that autumn; this time they went on a more honourable footing: James was created King's Commissioner to Scotland.[48] Separated from Lady Isabella once again, Mary sank into a state of sadness, exacerbated by the passing of the Exclusion bill in the Commons.[49][50] Lady Isabella, thus far the only one of Mary's children to survive infancy, died in February 1681.[51] Isabella's death plunged Mary into a religious mania, worrying her physician.[51] At the same time as news reached Holyrood of Isabella's death, Mary's mother was falsely accused of offering £10,000 for the murder of the King.[51] The accuser, a pamphleteer, was executed by order of the King.[51]

The Exclusionist reaction that followed the Popish plot had died down by May 1682.[52] Exclusionist-dominated Parliament, suspended since March 1681, never again met in the reign of Charles II.[53] Therefore, the Duke and Duchess of York returned to England, and the Duchess gave birth to Princess Charlotte Mary in August 1682; Charlotte Mary's death three weeks later, according to the French ambassador, robbed James of "hope that any child of his can live"—all James's sons by Anne Hyde, his first wife, died in infancy.[54] James's sadness was dispelled by his revival in popularity following the discovery of a plot to kill the King and him.[55] The objective of the plot, known as the Rye House Plot, was to have Monmouth placed on the throne as Lord Protector.[56] The revival was so strong that, in 1684, James was re-admitted to the Privy Council, after an absence of eleven years.[57]

Queen (1685–1689)

Despite all the furore over Exclusionism, James ascended to his brother's thrones easily upon the latter's death, which occurred on 6 February 1685 OS, possibly because the said alternative could provoke another civil war.[58] Mary sincerely mourned Charles, recalling in later life, "He was always kind to me."[59] Mary and James's £119,000 joint coronation ceremony, occurring on 23 April OS, Saint George's day, was meticulously planned.[60][61] Precedents were sought for Mary because a full-length joint coronation had not occurred since the ceremony performed for Henry VIII of England and Catherine of Aragon.[60]

Queen Mary with her son, James Francis Edward, by Benedetto Gennari the Younger.

Queen Mary's health had still not recovered after the death of Lady Isabella. So much so, in fact, that the Tuscan envoy reported to Florence that "general opinion opinion turns [for Mary's successor] in the direction of the Princess, Your Highness's daughter".[62][63] France, too, was preparing for the Queen's imminent demise, putting forward as its candidate for James's new wife the Duke of Enghien's daughter.[62] The Queen was then trying to make her brother, the Duke of Modena, marry the former, Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici.[64]

In February 1687, the Queen, at the time irritated by the King's affair with Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester, moved into new apartments in Whitehall; Whitehall had been home to a Catholic chapel since December 1686.[65][66] Her apartments were designed by Christopher Wren at the cost of £13,000.[67] Because the palace's renovation was thus far unfinished, the King received ambassadors in her rooms, much to the Queen's chagrin.[68] Five months later, shortly after the marriage talks with Tuscany collapsed, the Queen's mother, Duchess Laura, died.[69] Therefore, the whole English court went into mourning.[69] Duchess Laura left Mary "a considerable sum of cash" and some jewellery.[70] William III of Orange, James's son-in-law, sensed popular discontent with James's government; he used the death of Mary's mother as a guise to send his half-uncle, Count Zuylestein, to England, ostensibly to condole Queen Mary, but really to spy.[71][72]

Having visited Bath, in the hope its waters would aid conception, Queen Mary became pregnant in late 1687.[73] When the pregnancy became public knowledge shortly before Christmas, Catholics rejoiced.[74] Protestants, who had tolerated James's Catholic government because he had no Catholic heir, were concerned.[75] The Protestant disillusion came to a head after the child's male sex became known, when many Protestants chose to believe the child was illegitimate.[76] They did this to prevent the perpetuation of James II's Catholic dynasty.[76] Popular opinion alleged that the child, named James Francis Edward, was sneaked into the birth chamber as a substitute to the Queen's real but stillborn child.[76] This rumour was widely accepted as fact by Protestants, despite the fact the birth-chamber was intentionally packed full of 200 witnesses, both Protestant and Catholic.[76][77] Princess Anne of Denmark[note 3] answered a memorandum of 18 questions regarding James Francis Edward's birth for her sister, the Princess of Orange.[71] Anne's answers, biased and unreliable, convinced the Princess of Orange that her father had thrust a changeling upon the nation.[71] Count Zuylestein, returning to the Netherlands shortly after the birth, agreed with Anne's findings.[71]

Issued by seven leading Whig nobles, the invitation for William to invade England signalled the beginning of a revolution that culminated in James II's deposition.[78] The invitation assured William that "nineteen parts of twenty of the people throughout the kingdom" wished for an intervention.[78] The revolution, known as the Glorious Revolution, deprived James Francis Edward of his right to the English throne, on the grounds he was not the King's real son and, later, because he was a Catholic.[78] England in the hands of William of Orange's 15,000-strong army, James and Mary went into exile in France.[78] There, they stayed at the expense of King Louis XIV, who supported the Jacobite cause.[78][79]

Queen over the water (1689–1701)

Reception at Louis XIV's court

As Mary II and William III & II had ascended the English and Scottish thrones, Mary of Modena ceased to be Queen of England on 11 December 1688 OS and of Scotland on 11 May 1689 OS.[80] This was concurrent with her husband's formal deposition. James II, however, backed by Louis XIV of France, still considered himself king by divine right and maintained it was not within parliament's prerogative to depose a monarch.[81]

Louis XIV gave the exiled King and Queen the use of Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where they set up court-in-exile.[79][82] Mary soon became a popular fixture at Louis XIV's court at Versailles, where diarist Madame de Sévigné acclaimed Mary for her "distinguished bearing and her quick wit".[83] Questions of precedence, however, marred Mary's relations with the Dauphine of France, Maria Anna of Bavaria.[83] Because Mary was accorded the privileges and rank of a queen, Maria Anna was outranked by her.[83] Therefore, Maria Anna refused to see Mary, etiquette being a sensitive issue at Versailles.[84] In spite of this, Louis XIV and his secret wife, Madame de Maintenon, became close friends with Mary.[83] James was excluded from French court life as contemporaries found him boring.[83][85] Mary gave birth to Princess Louise Mary in 1692.[83] She was to be James and Mary's last child.

Initially supported by Irish Catholics in his effort to regain the thrones, James launched an expedition to Ireland in March 1689.[86] He abandoned it upon his defeat at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.[86] During James's campaign, Mary supported his cause throughout the British Isles: she sent three French supply ships to Bantry Bay and £2,000 to Jacobite rebels in Dundee.[87] She financed those measures by selling her jewellery.[88] Money problems plagued the Stuart court-in-exile, despite a substantiaal pension from Louis XIV of 50,000 livres.[79] Mary tried her best to assist those of her husband's followers living in poverty, and encouraged her children to give part of their pocket money to Jacobite refugees.[89][90][91]

Estensi succession

The collapse of James's invasion of Ireland in 1691 upset Mary. Her spirits were lifted by news of Mary's brother the Duke of Modena's marriage.[92] He married Margherita Maria Farnese of Parma.[92] When, in 1695, Mary's brother died, the House of Este was left with one progenitor, Cardinal-Duke Rinaldo.[93] Queen Mary, concerned for the dynasty's future, urged the Cardinal-Duke to resign his cardinalate, "for the good of the people and for the perpetuation of the sovereign house of Este".[94] Duke Rinaldo's bride, Princess Charlotte Felicitas of Brunswick-Lüneburg, was, according to Mary, "of an easy disposition best suited to [the Duke]".[94]

A bone of contention, however, arose over the Queen's inheritance and dowry.[95] Duke Rinaldo refused to release the former, and left the latter £15,000 in arrears.[96] In 1700, five years later, the Duke finally paid the Queen her dowry; her inheritance, however, remained sequestered, and relations with Modena worsened again when Rinaldo allied himself with Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I.[97] Leopold was an enemy of Louis XIV, James and Mary's patron.[97]

Regency

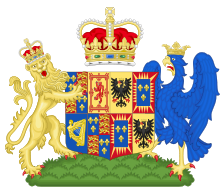

Queen Mary's coat of arms as Queen consort of England.[98] Depicting the Royal Coat of Arms of England, Scotland and Ireland impaled with a minor version of her father's arms as Duke of Modena. In light of religious sentiment at the time, it was presumed unwise to reproduce her father's arms in full, since the quarterings are divided by a "Pale Gules charged with the Papal keys ensigned with the Tiara".[99]

Queen Mary's coat of arms as Queen consort of England.[98] Depicting the Royal Coat of Arms of England, Scotland and Ireland impaled with a minor version of her father's arms as Duke of Modena. In light of religious sentiment at the time, it was presumed unwise to reproduce her father's arms in full, since the quarterings are divided by a "Pale Gules charged with the Papal keys ensigned with the Tiara".[99]

In March 1701, James II suffered a stroke while hearing mass at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, leaving him partially paralysed.[100] Fagon, Louis XIV's personal physician, recommend the waters of Bourbon-l'Archambault, to cure the King's paralysis.[101] The waters, however, had little effect, and James II died of a seizure on 16 September 1701.[102] Louis XIV, in contravention of the Peace of Ryswick, declared James Francis Edward King of England, Ireland and Scotland as James III and VIII.[103] This act irritated King William III and II, who had ruled alone since the death of his wife, Mary II.[104] Because James Francis Edward was a minor, Queen Mary acted as nominal regent for her son.[105] Mary presided over his regency council, too, although she was uninterested in politics.[105] Before his death, James II expressed his wish that Mary's regency would last no longer than their son's 18th birthday.[106]

Dressed in mourning for the remainder of her life, Queen Mary's first act as regent was to disseminate a manifesto, outlining James Francis Edward's claims.[107] It was largely ignored in England.[107] In Scotland, however, the confederate Lords sent Lord Belhaven to Saint-Germain, to convince the Queen to surrender to them custody of James Francis Edward and accede to his conversion to Protestantism.[107]

James Francis Edward Stuart, Mary of Modena's only surviving son, in a portrait by Antonio David.[96]

James Francis Edward Stuart, Mary of Modena's only surviving son, in a portrait by Antonio David.[96]

The conversion, said Belhaven, would enable James Francis Edward's accession to the English throne upon William III's death.[108] The Queen-Regent was not swayed by Belhaven's argument, so a compromise was reached: James Francis Edward, if he became King, would limit the number of Roman Catholic priests in England and promise not to tamper with the established Church of England.[108] In exchange, the confederate Lords would do all in their power to block the passing of the Hanoverian succession in Scottish parliament.[108] When, in March 1702, William III died, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, declared for James Francis Edward at Inverness.[109] Soon after, Lovat travelled to the court-in-exile at Saint-Germain, and begged the Queen-Regent to allow her son to come to Scotland.[109] Lovat intended to raise an army of 15,000 soldiers in Scotland, to seize the throne for James Francis Edward.[109] Mary refused to part with James Francis Edward, and the rising failed.[109] Mary's regency ceased with her son's reaching of the age of 16.[110]

Having wished to become a nun in her youth, Queen Mary sought refuge from the stresses of exile at the Convent of the Visitations, Chaillot, near Paris, where she befriended Louis XIV's penitent mistress, Louise de La Vallière.[111] There, Mary stayed with her daughter for long periods almost every summer.[112] It was here, too, in 1711, that Queen Mary found out that, as part of the embryonic Treaty of Utrecht, James Francis Edward was to lose Louis XIV's explicit recognition and be forced to leave France.[112] The next year, when James Francis Edward was expelled and Louise Mary died of smallpox, Mary was very upset;[113] according to Mary's close friend Madame de Maintenon, Mary was "a model of desolation".[113] Deprived of the company of her family, Queen Mary lived out the rest of her days at Chaillot and Saint-Germain in virtual poverty, unable to travel by her own means because all her horses had died and she could not afford to replace them.[114]

Following her death from cancer on 7 May 1718, Mary was remembered fondly by her French contemporaries, three of whom, Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, the Duke of Saint-Simon and the Marquis of Dangeau, deemed her a "saint".[115][116] Mary's remains were interred in Chaillot among the nuns she had befriended.[117]

Issue

Children of Mary of ModenaAncestry

Ancestors of Mary of Modena 16. Cesare d'Este 8. Alfonso III d'Este 17. Virginia de' Medici 4. Francesco I d'Este 18. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy 9. Isabella of Savoy 19. Catherine Michelle of Spain 2. Alfonso IV d'Este 20. Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma 10. Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma 21. Infanta Maria of Guimarães 5. Maria Caterina Farnese of Parma 22. Giovanni Francesco Aldobrandini 11. Margherita Aldobrandini 23. Olimpia Aldobrandini 1. Mary of Modena 24. Giovanni Battista Martinozzi 12. Vincenzo Martinozzi 25. Bianca Lanci 6. Hieronymus Martinozzi 26. Matteo Marcolini 13. Margherita Marcolini 27. Tommosa Bertozzi 3. Laura Martinozzi 28. Girolamo Mazarini 14. Peter Mazarini 29. Margherita de Franchis Passavera 7. Laura Mazarini 30. Giulio Buffalini, Count of San Giustino 15. Hortense Buffalini 31. Francesca Belloni Notes

- ^ Modena and France used the Gregorian calendar (NS), while England used the Julian one (OS). Therefore, for the duration of the 17th century, English dates were ten days behind Modena and France. From 29 February 1700 to 14 September 1752 the difference was eleven days.

- ^ This is equivalent to £959358 in present day terms.[18]

- ^ James's daughter Lady Anne of York had married Prince George of Denmark in 1683.

References

Citations

- ^ Harris, p 1.

- ^ Oman, p 30.

- ^ a b Encyclopaedia Brittanica. "Mary of Modena (queen of England)". Brittanica.com. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/367570/Mary-of-Modena. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ a b Oman, p 40.

- ^ Oman, p 14.

- ^ Haile, p 16.

- ^ Oman, p 15.

- ^ Waller, p 22.

- ^ Waller, p 23.

- ^ Haile, p 18.

- ^ Fea, p 70.

- ^ Oman, p 19.

- ^ a b c Waller, p 15.

- ^ Oman, p 10.

- ^ Haile, p 17.

- ^ Haile, p 24.

- ^ Oman, p 27.

- ^ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Lawrence H. Officer (2010) "What Were the UK Earnings and Prices Then?" MeasuringWorth.

- ^ a b Fraser. King Charles II, p 418.

- ^ a b Oman, p 28.

- ^ Haile, p 40.

- ^ Waller, p 135.

- ^ Waller, p 149.

- ^ Haile, p 41.

- ^ Turner, p 114.

- ^ Oman, p 31.

- ^ a b Chapman, p 33.

- ^ a b Waller, p 22

- ^ Waller, p 24.

- ^ Oman, p 46.

- ^ Oman, p 38.

- ^ a b c Oman, p 45.

- ^ Oman, p 48.

- ^ Marshall (2003). p. 172.

- ^ Fraser. King Charles II, p 463

- ^ Fraser. King Charles II, p 470.

- ^ Haile, p 76.

- ^ Chapman, p 67.

- ^ Brown, pp. 10–12

- ^ Fea, p 83.

- ^ Oman, p 56.

- ^ Haile, p 88.

- ^ a b c Oman, p 63.

- ^ Fea, p 85.

- ^ Haile, p 92.

- ^ Turner, p 171.

- ^ Oman, p 67.

- ^ Fea, p 96.

- ^ Waller, p 35

- ^ Haile, pp. 99–100

- ^ a b c d Oman, p 71.

- ^ Waller, p 36.

- ^ Waller, p 37.

- ^ Haile, p 109.

- ^ Oman, p 75.

- ^ Oman, pp. 75–76

- ^ Fraser. King Charles II, p 569.

- ^ Waller, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Oman, plate no. VII

- ^ a b Oman, p 85.

- ^ Haile, p 129.

- ^ a b Haile, p 124.

- ^ Waller, p 40.

- ^ Oman, p 96.

- ^ Fea, p 138.

- ^ Haile, p 142.

- ^ Oman, p 98.

- ^ Oman, p 99

- ^ a b Haile, p 159.

- ^ Oman, p 99.

- ^ a b c d Chapman, p 144.

- ^ Haile, p 163.

- ^ Waller, p 11.

- ^ Harris, p 239.

- ^ Waller, p 12.

- ^ a b c d Oman, pp. 108 – 109.

- ^ Harris, pp. 239 – 240.

- ^ a b c d e Waller, p 216.

- ^ a b c d Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, p 270.

- ^ Harris, p 325.

- ^ Starkey, p 190.

- ^ Uglow, p 523.

- ^ a b c d e f Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, p 271.

- ^ Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, pp. 270 – 271.

- ^ Oman, p 148.

- ^ a b Fea, p 235.

- ^ Oman, p 158.

- ^ Oman, pp. 158 – 159.

- ^ Oman, p 173.

- ^ Oman, p 207.

- ^ Haile, p 357.

- ^ a b Haile, p 282.

- ^ Haile, p 311.

- ^ a b Haile, p 312.

- ^ Haile, p 314.

- ^ a b Oman, p 184.

- ^ a b Oman, p 185.

- ^ Maclagan, Michael; Louda, Jiří, p 27.

- ^ Pinces, John Harvey; Pinces, Rosemary (1974). The Royal Heraldry of England. Heraldry Today. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. pp. 187. ISBN 090045525X

- ^ Gregg, p 127.

- ^ Oman, p 190.

- ^ Fea, p 285.

- ^ Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, p 322.

- ^ Gregg, p 101.

- ^ a b Oman, p 196.

- ^ Oman, p 197.

- ^ a b c Haile, p 358.

- ^ a b c Haile, p 359.

- ^ a b c d Haile, p 363.

- ^ Oman, plate xiv.

- ^ Haile, p 229.

- ^ a b Oman, p 221.

- ^ a b Oman, p 225.

- ^ Oman, p 242.

- ^ Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, p 383.

- ^ Oman, p 245.

- ^ Oman, p 247.

- ^ "Stuart, Catherine Laura". University of Hull. 7 March 2005. http://www3.dcs.hull.ac.uk/cgi-bin/gedlkup/n=royal?royal00716. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Stuart, Charles of Cambridge, Duke of Cambridge". University of Hull. 7 March 2005. http://www3.dcs.hull.ac.uk/cgi-bin/gedlkup/n=royal?royal00717. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Stuart, Charlotte Maria". University of Hull. 7 March 2005. http://www3.dcs.hull.ac.uk/cgi-bin/gedlkup/n=royal?royal00718. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Fraser, Love and Louis XIV, p 329.

Bibliography

- Allan, Fea (1909). James II and His Wives. Meuthon and Co.

- Brown, Beatrice Curtis (1929). Anne Stuart: Queen of England. Geoffrey Bles.

- Chapman, Hester (1953). Mary II, Queen of England. Jonathan Cape.

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). King Charles II Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-1403-1

- Fraser, Antonia (2007). Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2293-7

- Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Haile, Martin (1905). Queen Mary of Modena: Her Life and Letters. J.M. Dent & Co.

- Harris, Tim. (2007). Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy 1685–1720. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-01652-8

- Maclagan, Michael; Louda, Jiří (1999). Line of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 0856054691

- Marshall, Rosalind (2003) Scottish Queens, 1034-1714. Tuckwell Press.

- Oman, Carola (1962). Mary of Modena. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Starkey, David (2007). Monarchy: From the Middle Ages to Modernity. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-724766-0.

- Turner, FC (1948). James II. Eyre & Spottswoode.

- Uglow, Jenny (2009). A Gambling Man: Charles II and the Restoration. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21733-5

- Waller, Maureen (2002). Ungrateful Daughters: The Stuart Princesses Who Stole Their Father's Crown. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-79461-5

External links

Media related to Mary of Modena at Wikimedia CommonsMary of ModenaBorn: 5 October 1658 Died: 7 May 1718

Media related to Mary of Modena at Wikimedia CommonsMary of ModenaBorn: 5 October 1658 Died: 7 May 1718British royalty Preceded by

Catherine of BraganzaQueen consort of England and Scotland

1685–1688Act of Union 1707 Queen consort of Ireland

1685–1688Vacant Title next held byCaroline of Ansbach

as queen of Great BritainTitles in pretence Glorious Revolution — TITULAR —

Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland

1688–1701Succeeded by

Clementina SobieskaPrincesses of Modena Generations start from Ercole I d'Este, first Duke of Modena1st Generation Isabella, Marchioness of Mantua · Beatrice, Duchess of Milan · Princess Caterina · Princess Angela Caterina2nd Generation Princess Leonora · Princess Isabella Maria3rd Generation Anna, Duchess of Guise, Duchess of Nemours · Lucrezia, Duchess of Urbino · Princess Eleonora · Princess Angela Caterina4th Generation Princess Julia · Maria Laura, Duchess of Mirandola · Princess Caterina · Princess Angela Caterina5th Generation Princess Caterina Maria · Margarete, Duchess of Guastalla · Princess Beatrice · Princess Beatrice · Anna Beatrice, Duchess of Mirandola · Ippolita, Lady of Montecchio and Scandiano6th Generation Isabella, Duchess of Parma · Princess Leonore · Princess Eleonore · Maria, Duchess of Parma · Princess Vittoria · Matilde, Countess of Novellara · Maria Angela Caterina, Princess of Carignan · Princess Julia · Princess Julia7th Generation Maria Beatrice, Queen of England · Princess Benedetta · Amalia, Marchioness of Villeneuf · Enrichetta, Duchess of Parma8th Generation Maria Teresa Felicitas, Duchess of Penthièvre · Princess Mathilde · Maria Fortunata, Princess of Conti · Maria Anna, Princess of Paliano9th Generation 10th Generation Maria Theresa, Queen of Sardinia* · Princess Josepha* · Maria Leopoldine, Electress of Bavaria* · Princess Maria Antonia* · Maria Ludovika, Empress of Austria*11th Generation Maria Theresa, Duchess of Orléans* · Maria Beatrix, Countess of Montizón*12th Generation Princess Anna Beatrice* · Maria Theresa, Queen of Bavaria**also Archduchess of AustriaEnglish Royal Consorts Matilda of Flanders (1066–1083) · Matilda of Scotland (1100–1118) · Adeliza of Louvain (1121–1135) · Matilda I of Boulogne (1135–1152) · (Geoffrey V of Anjou?) (1141) · Eleanor of Aquitaine (1154–1189) · Margaret of France (1172–1183) · Berengaria of Navarre (1191–1199) · Isabella of Angoulême (1200–1216) · Eleanor of Provence (1236–1272) · Eleanor of Castile (1272–1290) · Margaret of France (1299–1307) · Isabella of France (1308–1327) · Philippa of Hainault (1328–1369) · Anne of Bohemia (1383–1394) · Isabella of Valois (1396–1399) · Joanna of Navarre (1403–1413) · Catherine of Valois (1420–1422) · Margaret of Anjou (1445–1471) · Elizabeth Woodville (1464–1483) · Anne Neville (1483–1485) · Elizabeth of York (1486–1503) · Catherine of Aragon (1509–1533) · Anne Boleyn (1533–1536) · Jane Seymour (1536–1537) · Anne of Cleves (1540) · Catherine Howard (1540–1542) · Catherine Parr (1543–1547) · (Lord Guilford Dudley?) (1553) · Anne of Denmark (1603–1619) · Henrietta Maria of France (1625–1649) · Catherine of Braganza (1662–1685) · Mary of Modena (1685–1688) · George of Denmark (1702–1707)Scottish Royal Consorts Elizabeth de Burgh (1306–1327) · Joan of The Tower (1329–1362) · Margaret Drummond (1364–1369) · Euphemia de Ross (1371–1386) · Anabella Drummond (1390–1401) · Joan Beaufort (1424–1437) · Mary of Guelders (1449–1460) · Margaret of Denmark (1469–1486) · Margaret Tudor (1503–1513) · Madeleine of Valois (1537) · Mary of Guise (1538–1542) · Francis II of France (1558–1560) · Henry, Duke of Albany (1565–1567) · James, Earl of Bothwell (1567) · Anne of Denmark (1589–1619) · Henrietta Maria of France (1625–1649) · Catherine of Braganza (1662–1685) · Mary of Modena (1685–1688) · George, Duke of Cumberland (1702–1707)Categories:- English royal consorts

- Scottish royal consorts

- 1658 births

- 1718 deaths

- 17th-century Italian people

- 18th-century Italian people

- 17th-century women

- 18th-century women

- Cancer deaths in France

- Duchesses of York

- House of Este

- House of Stuart

- Italian Roman Catholics

- English Roman Catholics

- Jacobites

- People from Modena

- Modenese princesses

- James II of England

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.