- Scottish literature

-

- "Scottish Fiction" redirects here; for the Idlewild album, see Scottish Fiction: Best of 1997–2007.

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes literature written in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin and any other language in which a piece of literature was ever written within the boundaries of modern Scotland.

The earliest extant literature written in what is now Scotland, was composed in Brythonic speech in the 6th century and has survived as part of Welsh literature. In the following centuries there was literature in Latin, under the influence of the Catholic Church, and in Old English, brought by Anglian settlers. As the state of Alba developed into the kingdom of Scotland from the 8th century, there was a flourishing literary elite who regularly produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin, sharing a common literary culture with Ireland and elsewhere. After the Davidian Revolution of the 13th century a flourishing French language culture predominated, while Norse literature was produced from areas of Scandinavian settlement. The first surviving major text in Early Scots literature is the 14th century poet John Barbour's epic Brus, which was followed by a series of vernacular versions of medieval romances. These were joined in the 15th century by Scots prose works.

In the early modern era royal patronage supported poetry, prose and drama. James V's court saw works such as Sir David Lindsay of the Mount's The Thrie Estaitis. In the late 16th century James VI became patron and member of a circle of Scottish court poets and musicians known as the Castalian Band. When he acceded to the English throne in 1603 many followed him to the new court, but without a centre of royal patronage the tradition of Scots poetry subsided. It was revived after union with England in 1707 by figures including Allan Ramsay and James Macpherson. The latter's Ossian Cycle made him the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation. He helped inspire Robert Burns, considered by many to be the national poet, and Walter Scott, whose Waverley Novels did much to define Scottish identity in the 19th century. Towards the end of the Victorian era a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, including Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, J. M. Barrie and George MacDonald.

In the 20th century there was a surge of activity in Scottish literature, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure, Hugh MacDiarmid, attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature. Members of the movement were followed by a new generation of post-war poets including Edwin Morgan, who would be appointed the first Scots Makar by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers including Irvine Welsh. Scottish poets that emerged in the same period included Carol Anne Duffy, who was named as first Scott to be UK Poet Laureate in May 2009.

Contents

The early middle ages

Earliest literature from within modern Scotland

The people of northern Britain spoke forms of Celtic languages. Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually composed in or near the country we now call Scotland, as Brythonic speech (the ancestor of Welsh) was not then confined to Wales and Cornwall. While all modern scholarship indicates that the Picts spoke a Brythonic language (based on surviving placenames, personal names and historical evidence), none of their literature seems to have survived into the modern era.

Some of the earliest literature known to have been composed in Scotland includes:

- Brythonic (Old Welsh):

- The Gododdin (attributed to Aneirin), c. 6th century[1]

- The Battle of Gwen Ystrad (attributed to Taliesin), late 6th century.[1]

- Gaelic:

- Latin:

- Old English

- The Dream of the Rood, c. 700 (the only surviving fragment of Northumbrian Old English from early Medieval Scotland).[4]

The high middle ages

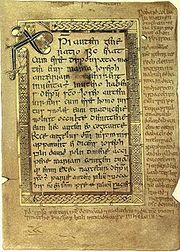

Book of Deer, Folio 5r contains the text of the Gospel of Matthew from 1:18 through 1:21. Note the Chi Rho monogram in the upper left corner. The margins contain Gaelic text.

Book of Deer, Folio 5r contains the text of the Gospel of Matthew from 1:18 through 1:21. Note the Chi Rho monogram in the upper left corner. The margins contain Gaelic text.

Before the reign of David I (1124–53) brought Norman and Anglo-French culture to the court, the Scots possessed a flourishing literary elite who regularly produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin that were frequently transmitted to Ireland and elsewhere. A Gaelic literary elite survived in the eastern Scottish lowlands, in places such as Loch Leven and Brechin into the 13th century,[5] It is possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in medieval Scotland than is often thought, but has not survived because the Gaelic literary establishment of eastern Scotland died out before the 14th century. Thomas Owen Clancy has argued that the Lebor Bretnach, the so-called "Irish Nennius," was written in Scotland, and probably at the monastery in Abernethy, but this text survives only from manuscripts preserved in Ireland.[6] Other literary work which has survived include that of the prolific poet Gille Brighde Albanach. About 1218, Gille Brighde wrote a poem — Heading for Damietta — on his experiences of the Fifth Crusade.[7]

In the 13th century, French flourished as a literary language, and produced the Roman de Fergus, the earliest piece of non-Celtic vernacular literature to survive from Scotland. Many other stories in the Arthurian Cycle, written in French and preserved only outside Scotland, are thought by some scholars (D.D.R. Owen for instance) to have been written in Scotland. There is no extant literature in the English language in this era. There is some Norse literature from areas of Scandinavian settlement, such as the Northern Isles and the Western Isles. The famous Orkneyinga Saga however, although it pertains to the Earldom of Orkney, was written in Iceland.

In addition to French, Latin too was a literary language, with works that include the "Inchcolm Antiphoner" and the "Carmen de morte Sumerledi", a poem which exults triumphantly the victory of the citizens of Glasgow over Somailre mac Gilla Brigte. What is arguably the most important medieval work written in Scotland, the Vita Columbae, was also written in Latin.

Late medieval Anglo-Scottish literature

James I, who spent much of his life imprisoned in England, where he gained a reputation as a musician and poet.

James I, who spent much of his life imprisoned in England, where he gained a reputation as a musician and poet.

The first surviving major text in Early Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion till the end of the war of independence.[8] The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer in England.[9] In the early 15th century these were followed by Andrew of Wyntoun's verse Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland and Blind Harry's The Wallace, which blended historical romance with the verse chronicle. They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, including The Buik of Alexander, Launcelot o the Laik and The Porteous of Noblenes by Gibert Hay.[10]

Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I (who wrote The Kingis Quair). Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with the Kirk. However, Dunbar's Lament for the Makaris (c.1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost.[11] Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry.[10]

In the late 15th century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the Auchinleck Chronicle,[12] the first complete surviving work includes John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490).[13] There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including The Book of the Law of Armys and the Order of Knychthode and the treatise Secreta Secetorum, an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great.[10] The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid, the Eneados, which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.[10]

Early modern literature

As a patron of poets and authors James V supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, who translated the Latin History of Scotland compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece, into verse and prose. Sir David Lindsay of the Mount the Lord Lyon, the head of the Lyon Court and diplomat, was a prolific poet. He produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace thought to be a version of his play The Thrie Estaitis in 1540, the first surviving full Scottish play, which satirised the corruption of church and state.[14]

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI promoted the literature of the country of his birth. His treatise, Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody, published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, Scots, to which he applied Renaissance principles.[15] He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, the Castalian Band, which included William Fowler and Alexander Montgomerie, the latter being a favourite of the King.[16] By the late 1590s his championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne,[17] and some courtier poets who followed the king to London after 1603, such as William Alexander, began to anglicise their written language.[18] James's characteristic role as active literary participant and patron in the Scottish court made him a defining figure for English Renaissance poetry and drama, which would reach a pinnacle of achievement in his reign,[19] but his patronage for the high style in his own Scottish tradition largely became sidelined.[20]

The Scottish ballad tradition can be traced back to the early 17th century. Francis James Child's compilation, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (1882–1898) contains many examples, such as The Elfin Knight (first printed around 1610) and Lord Randal. In this period, Scotland began to see more anglicisation among some social classes, although Lowland Scots was still spoken by the vast majority of the population of the Lowlands. This was the time when many of the oral ballads from the borders and the North East began to be written down. Literary writers of the period include Robert Sempill (c.1595-1665), Lady Wardlaw and Lady Grizel Baillie.

18th century to the 19th century

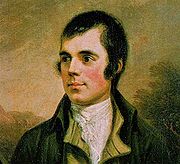

Robert Burns (1759-96) considered by many to be the Scottish national poet.

Robert Burns (1759-96) considered by many to be the Scottish national poet.

Although after union with England, Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.[21] James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by Ossian, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics. Fingal written in 1762 was speedily translated into many European languages, and its deep appreciation of natural beauty and the melancholy tenderness of its treatment of the ancient legend did more than any single work to bring about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German, literature, influencing Herder and Goethe.[22] Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from the Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.[23]

Robert Burns and Walter Scott were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.[24] Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[25] It launched a highly successful career that probably more than any other figure helped define and popularise Scottish cultural identity.[26]

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations. Robert Louis Stevenson's work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books like Kidnapped and Treasure Island. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. The "kailyard tradition" at the end of the century, brought elements of fantasy and folklore back into fashion as can be seen in the work of figures like J. M. Barrie, most famous for his creation of Peter Pan and George MacDonald whose works including Phantasies played a major part in the creation of the fantasy genre.[27]

20th century to the present

Main article: Scottish RenaissanceIn the early 20th century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance.[28] The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid (the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms.[28] Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A J Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie. All were born within a fifteen-year period (1887 and 1901) and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues.[28]

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch and Sydney Goodsir Smith. Others demonstrated a greater interest in English language poetry, among them Norman MacCaig, George Bruce and Maurice Lindsay.[28][29] George Mackay Brown from Orkney, and and Iain Crichton Smith from Lewis, wrote both poetry and prose fiction shaped by their distinctive island backgrounds.[28] The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004.[30] Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Muriel Spark, James Kennaway, Alexander Trocchi, Jessie Kesson and Robin Jenkins spent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes, as in Spark's Edinburgh-set The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961)[28] and Kennaway's script for the film Tunes of Glory (1956).[31] Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean, and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett.[28] A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Shena Mackay, Alan Spence, Allan Massie and the work of William McIlvanney.[28]

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum. Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Polygon Books. Members of the group that would come to prominence as writers included James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard and Aonghas MacNeacail.[28] In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting (1993), Warner’s Morvern Caller (1995), Gray’s Poor Things (1992) and Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late (1994).[28] These works were linked by a sometimes overtly political reaction to Thatcherism that explored marginal areas of experience and used vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots dialect). Scottish crime fiction has been a major area of growth with the success of novelists including Val McDermid, Frederic Lindsay, Christopher Brookmyre, Quentin Jardine, Denise Mina and particularly the success of Edinburgh’s Ian Rankin and his Inspector Rebus novels.[28] This period also saw the emergence of a new generation of Scottish poets that became leading figures on the UK stage, including Don Paterson, Robert Crawford, Kathleen Jamie and Carol Anne Duffy.[28] Glasgow-born Carol Ann Duffy was named as Poet Laureate in May 2009, the first woman, the first Scot and the first openly gay poet to take the post.[32]

See also

- Association for Scottish Literary Studies

- British literature

- History of the Scots language

- Scottish Gaelic literature

- Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry

- Modern Scottish Poetry (Faber)

- Sir Patrick Spens

- The Bonny Earl of Murray

- Book of Deer

- Walter Scott MacFarlane

- Books in the "Famous Scots Series"

References

- ^ a b R. T. Lambdin and L. C. Lambdin, Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature (London: Greenwood, 2000), ISBN 0313300542, p. 508.

- ^ a b J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1851094407, p. 999.

- ^ a b I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748616152, p. 94.

- ^ E. M. Treharne, Old and Middle English c.890-c.1400: an Anthology (Wiley-Blackwell, 2004), ISBN 1405113138, p. 108.

- ^ D. Broun, "Gaelic Literacy in Eastern Scotland between 1124 and 1249" in H. Pryce ed., Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies (Cambridge, 1998), ISBN 0521570395, pp. 183–201.

- ^ T. O. Clancy, "Scotland, the ‘Nennian’ recension of the Historia Brittonum, and the Lebor Bretnach", in S. Taylor, ed., Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297 (Dublin/Portland, 2000), ISBN 1-85182-516-9, pp. 87–107.

- ^ T. O. Clancy, (ed.), The Triumph Tree: Scotland's Earliest Poetry, 550–1350 (Edinburgh, 1998). pp. 247–283.

- ^ A. A. M. Duncan, ed., The Brus (Canongate, 1997), ISBN 0862416817, p. 3.

- ^ N. Jayapalan, History of English Literature (Atlantic, 2001), ISBN 8126900415, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 60-7.

- ^ Grant, Alexander, Independence and Nationhood, Scotland 1306-1469 (Baltimore: Edward Arnold, 1984), pp. 102-3.

- ^ T. Thomson, ed., Auchinleck Chronicle (Edinburgh, 1819).

- ^ J. Martin, Kingship and Love in Scottish poetry, 1424-1540 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 075466273X, p. 111.

- ^ I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748616152, pp. 256-7.

- ^ R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in The History of Scottish Literature, C. Cairns, ed., (Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1, ISBN 0080377289, pp. 126–7.

- ^ R. D. S. Jack, Alexander Montgomerie, (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1985), ISBN 0-7073-0367-2, pp. 1–2.

- ^ R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed., The History of Scottish Literature (Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1, ISBN 0080377289, p. 137.

- ^ M. Spiller, "Poetry after the Union 1603–1660" in C. Cairns, ed., The History of Scottish Literature (Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1, ISBN 0080377289, pp. 141–52.

- ^ N. Rhodes, "Wrapped in the Strong Arm of the Union: Shakespeare and King James" in W. Maley and A. Murphy, eds, Shakespeare and Scotland, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), ISBN 0719066360, pp. 38–9.

- ^ R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed., The History of Scottish Literature (Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1, ISBN 0080377289, pp. 137–8.

- ^ J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 311, ISBN 0060558881.

- ^ J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 163, ISBN 0060558881.

- ^ D. Thomson (1952), The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian", Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd

- ^ L. McIlvanney (Spring 2005), "Hugh Blair, Robert Burns, and the Invention of Scottish Literature", Eighteenth-Century Life 29 (2): 25-46.

- ^ K. S. Whetter (2008), Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance, Ashgate, p. 28, ISBN 0754661423.

- ^ N. Davidson (2000), The Origins of Scottish Nationhood, Pluto Press, p. 136, ISBN 0745316085.

- ^ "Cultural Profile: 19th and early 20th century developments", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 5 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62yP6lcz7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Scottish 'Renaissance' and beyond", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 5 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62yGHJmza.

- ^ P. Kravitz (1999), Introduction to The Picador Book of Contemporary Scottish Fiction, Ted Smart, p. xxvii, ISBN 0330335502

- ^ The Scots Makar, The Scottish Government, 16 February 2004, archived from the original on 5 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62yPZX5d4, retrieved 2007-10-28

- ^ Royle, Trevor (1983), James & Jim: a Biography of James Kennaway, Mainstream, pp. 185–95, ISBN 9780906391464

- ^ "Duffy reacts to new Laureate post", BBC News, 1 May 2009, archived from the original on 5 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62yL0dlTE.

External links

- The Spread of Scottish Printing, digitised items between 1508 and 1900

Scotland topics

Scotland topicsHistory Geography Geology · Climate · Demographics · Mountains and hills · Islands · Lochs · Waterfalls · Fauna · Flora · Highlands · Lowlands · Central Belt · Anglo-Scottish borderEconomy Companies · Bank of Scotland · Royal Bank of Scotland · North Sea oil · Whisky · Tourism · Harris Tweed · Renewable energy · Transport · Saltire FoundationLaw People Politics Religion Languages Culture Clans · Cuisine · Education · Flags · Coat of arms · Anthem · Hogmanay · Innovations · Literature · Music · Sport · World Heritage Sites · National identity · National symbols · Scottish surnamesEuropean literature Abkhaz · Albanian · Armenian · British · Austrian · Azerbaijani · Basque · Belarusian · Belgian · Breton · Bulgarian · Catalan · Croatian · Cypriot · Czech · Danish · Dutch · Estonian · Faroese · Finnish · Flemish · French · Frisian · German · Greek (ancient · medieval · modern) · Hungarian · Icelandic · Irish · Italian · Jèrriais · Latvian · Lithuanian · Luxembourg · Macedonian · Maltese · Montenegrin · Manx · Norwegian · Occitan (Provençal) · Old English (Anglo-Saxon) · Ossetian · Polish · Portuguese · Romanian · Russian · Scottish · Serbian · Slovak · Slovene · Spanish · Swedish · Swiss · Turkish · Ukrainian · Welsh-language · Welsh in English · YiddishPoetry of different cultures and languages Albanian epic · American · Anglo-Welsh · Arabic · Australian · Bengali · Bishnupriya Manipuri · Biblical · Byzantine · Canadian · Chinese · Cornish · English · Finnish · French · Greek · Guernésiais · Gujarati · Hindi · Hebrew · Indian · Indian epic · Irish · Italian · Japanese · Javanese · Jèrriais · Kannada · Kashmiri · Korean · Latin · Latin American · Latino · Manx · Marathi · Malayalam · Nepali · Old English · Old Norse · Ottoman · Pakistani · Pashto · Persian · Polish · Punjabi · Rajasthani · Sanskrit (Classical · Vedic) · Scottish · Serbian epic · Sindhi · Slovak · Spanish · Tamil · Telugu · Turkish · Urdu · WelshCategories:- Scottish literature

- European literature

- History of literature in the United Kingdom

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.