- American Colonization Society

-

The three founders of the American Colonization Society were (left to right) John Randolph, Henry Clay and Richard Bland Lee.[1][2][3]

The American Colonization Society (in full, The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America), founded in 1816, was the primary vehicle to support the "return" of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. It helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22 as a place for freedmen. Its founders were Henry Clay, John Randolph, and Richard Bland Lee.[4][2][3]

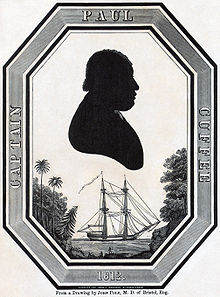

Paul Cuffee, a wealthy mixed-race New England shipowner and activist, was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa. He gained support from black leaders and members of the US Congress for an emigration plan. In 1811 and 1815-16, he financed and captained successful voyages to British-ruled Sierra Leone, where he helped African-American immigrants get established.[5] Although Cuffee died in 1817, his efforts may have "set the tone" for the American Colonization Society (ACS) to initiate further settlements.

The ACS was a coalition made up mostly of Quakers who supported abolition, and slaveholders who wanted to remove the perceived threat of free blacks to their society. They found common ground in support of so-called "repatriation". They believed blacks would face better chances for full lives in Africa than in the U.S. The slaveholders opposed abolition, but saw repatriation as a way to remove free blacks and avoid slave rebellions.[2] From 1821, thousands of free black Americans moved to Liberia from the United States. Over 20 years, the colony continued to grow and establish economic stability. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared the nation an independent state.

Critics have said the ACS was a racist society, while others point to its benevolent origins and later takeover by men with visions of an American empire in Africa. The Society closely controlled the development of Liberia until its declaration of independence. By 1867, the ACS had assisted in the movement of more than 13,000 Americans to Liberia. From 1825-1919, it published a journal, the African Repository and Colonial Journal. After that, the society had essentially ended, but did not formally dissolve until 1964, when it transferred its papers to the Library of Congress.[6]

Contents

Background

Colonization as a solution to the "problem" of free blacks

Following the American Revolutionary War, the "peculiar Institution" of slavery and those bound within it grew, reaching four million slaves by the mid-19th century.[7] At the same time, due in part to manumission efforts sparked by the war and the abolition of slavery in Northern states, there was an expansion of the ranks of free blacks with legislated limits.[2] In the first two decades after the Revolutionary War, the percentage of free blacks rose in Virginia, for instance, from 1% to nearly 10% of the black population.

Some men decided to support emigration following an abortive slave rebellion headed by Gabriel Prosser in 1800, and a rapid increase in the number of free African Americans in the United States, which was perceived by some to be alarming. Although the ratio of whites to blacks was 8:2 from 1790 to 1800, it was the increase in the number of free African Americans that disturbed some proponents of colonization. From 1790 to 1800, the number of free African Americans increased from 59,467 (1½ % of total U.S. population, 7½ % of U.S. black population) to 108,398 (2 % of U.S. population), a percentage increase of 82 percent; and from 1800 to 1810, the number increased from 108,398 to 186,446 (2½ % of U.S. pop.), an increase of 72 percent.[8] The perception of change was highest in some major cities, but especially the Upper South, where the most slaves were freed in the two decades after the Revolution.

This steady increase did not go unnoticed by an anxious white community that was ever more aware of the free blacks in their midst. The arguments propounded against free blacks, especially in free states, may be divided into four main categories. One argument pointed toward the perceived moral laxity of blacks. Blacks, it was claimed, were licentious beings who would draw whites into their savage, unrestrained ways. The fears of an intermingling of the races were strong and underlay much of the outcry for removal.

Along these same lines, blacks were accused of a tendency toward criminality.[9] Still others claimed that the supposed mental inferiority of African Americans made them unfit for the duties of citizenship and incapable of real improvement. Economic considerations were also put forth. Free blacks were said to threaten jobs of working class whites in the North.

Southerners had their special reservations about free blacks, fearing that the freedmen living in in slave areas caused unrest to slaves, and encouraged runaways and slave revolts. They had racist reservations about the ability of free blacks to function. The proposed solution was to have free blacks deported from the United States to colonize parts of Africa.[10]

Paul Cuffe

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817) was a mixed-race, successful Quaker ship owner descended from Ashanti and Wampanoag parents. He advocated settling freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. He had an economic interest, as he intended to bring back valuable cargoes. In 1816, Captain Cuffee took thirty-eight American blacks to Freetown, Sierra Leone; other voyages were precluded by his death in 1817. By reaching a large audience with his pro-colonization arguments and practical example, Cuffee laid the groundwork for the American Colonization Society.[11]

Origins

The ACS had its origins in 1816, when Charles Fenton Mercer, a Federalist member of the Virginia General Assembly, discovered accounts of earlier legislative debates on black colonization in the wake of Gabriel Prosser's rebellion. Mercer pushed the state to support the idea, and one of his political contacts in Washington City, John Caldwell, in turn contacted the Reverend Robert Finley, his brother-in-law, a Presbyterian minister, who endorsed the scheme.[citation needed]

The Society was officially established in Washington at the Davis Hotel on December 21, 1816. The founders were considered to be Henry Clay, John Randolph of Roanoke, and Richard Bland Lee. Mercer was unable to go to Washington for the meeting. Although the eccentric Randolph believed that the removal of free blacks would "materially tend to secure" slave property, the vast majority of early members were philanthropists, clergy and abolitionists who wanted to free African slaves and their descendants and provide them with the opportunity to "return" to Africa. Few members were slave-owners; the Society never enjoyed much support among planters in the Lower South. This was the area that developed most rapidly in the nineteenth century with slave labor, and initially it had few free blacks, who lived mostly in the Upper South.

Motives

The colonization effort resulted from a mixture of motives. Free blacks, freedmen and their descendants, encountered widespread discrimination in the United States of the early 19th century. They were generally perceived as a burden on society and a threat to white workers because they undercut wages. Some abolitionists believed that blacks could not achieve equality in the United States and would be better off in Africa. Many slaveholders were worried that the presence of free blacks would encourage slaves to rebel.

Despite being antislavery, Society members were openly racist and frequently argued that free blacks would be unable to assimilate into the white society of this country. John Randolph, one famous slave owner, called free blacks "promoters of mischief."[12] At this time, about 2 million African Americans lived in America of which 200,000 were free persons of color (with legislated limits).[2] Henry Clay, a congressman from Kentucky who was critical of the negative impact slavery had on the southern economy, saw the movement of blacks as being preferable to emancipation in America, believing that "unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off".[13] Clay argued that because blacks could never be fully integrated into U.S. society due to "unconquerable prejudice" by white Americans, it would be better for them to emigrate to Africa.[13]

Finley suggested at the inaugural meeting of an African Society that a colony be established in Africa to take free people of color, most of whom had been born free, away from the United States. Rev. Finley meant to colonize "(with their consent) the free people of color residing in our country, in Africa, or such other place as Congress may deem most expedient." The organization established branches throughout the United States. It was instrumental in the establishment of the colony of Liberia.

Fundraising

During the next three years, the society raised money by selling membership. The Society's members relentlessly pressured Congress and the President for support. In 1819, they received $100,000 from Congress and in January 1820 the first ship, the Elizabeth, sailed from New York for West Africa with three white ACS agents and 88 emigrants aboard.

The ACS purchased the freedom of American slaves and paid their passage to Liberia. Emigration was offered to already free black people. For many years the ACS tried to persuade the US Congress to appropriate funds to send colonists to Liberia. Although Henry Clay led the campaign, it failed. The society did, however, succeed in its appeals to some state legislatures. In 1850, Virginia set aside $30,000 annually for five years to aid and support emigration. In its Thirty-Fourth Annual Report, the society acclaimed the news as "a great Moral demonstration of the propriety and necessity of state action!" During the 1850s, the society also received several thousand dollars from the New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Maryland legislatures.

Preparation of colony

Jehudi Ashmun, an early leader of the ACS colony, envisioned an American empire in Africa. During 1825 and 1826, Ashmun took steps to lease, annex, or buy tribal lands along the coast and along major rivers leading inland. Like his predecessor Lt. Robert Stockton, who in 1821 established the site for Monrovia by "persuading" a local chief referred to as "King Peter" to sell Cape Montserado (or Mesurado) by pointing a pistol at his head, Ashmun was prepared to use force to extend the colony's territory. His aggressive actions quickly increased Liberia's power over its neighbors. In a treaty of May 1825, King Peter and other native kings agreed to sell land to Ashmun in return for 500 bars of tobacco, three barrels of rum, five casks of powder, five umbrellas, ten iron posts, and ten pairs of shoes, among other items. (The treaty is included in papers of the ACS in the U.S. Library of Congress.)

First colony

The ship pulled in first at Freetown, Sierra Leone, from where it sailed south to what is now the northern coast of Liberia. The emigrants started to establish a settlement. All three whites and 22 of the emigrants died within three weeks from yellow fever. The remainder returned to Sierra Leone and waited for another ship. The Nautilus sailed twice in 1821 and established a settlement at Mesurado Bay on an island they named Perseverance. It was difficult for the early settlers, made of mostly free-born blacks who had been denied the full rights of United States citizenship. In Liberia, the native Africans resisted the expansion of the colonists, resulting in many armed conflicts between them. Nevertheless, in the next decade 2,638 African Americans migrated to the area. Also, the colony entered an agreement with the U.S. Government to accept freed slaves who were taken from illegal slave ships.

Expansion and growth of the colony

During the next 20 years the colony continued to grow and establish economic stability. Since the establishment of the colony, the ACS employed white agents to govern the colony. In 1842, Joseph Jenkins Roberts became the first non-white governor of Liberia. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared itself an independent state, with J.J. Roberts elected as its first President.

The society in Liberia developed into three segments: The settlers with European-African lineage; freed slaves from slave ships and the West Indies; and indigenous native people. These groups would have a profound affect on the history of Liberia.

African Repository and Colonial Journal

In March 1825, the ACS began a quarterly, The African Repository and Colonial Journal, edited by Rev. Ralph Randolph Gurley (1797–1872), who headed the Society until 1844. Conceived as the Society's propaganda organ, the Repository promoted both colonization and Liberia. Among the items printed were articles about Africa, letters of praise, official dispatches stressing the prosperity and steady growth of the colony, information about emigrants, and lists of donors.

Lincoln and the ACS

Since the 1840s Lincoln, an admirer of Clay, had been an advocate of the ACS program of colonizing blacks in Liberia. In an 1854 speech in Illinois, he points out the immense difficulties of such a task are an obstacle to finding an easy way to quickly end slavery.[14]

Early in his presidency, Abraham Lincoln tried repeatedly to arrange resettlement of the kind the ACS supported, but each arrangement failed (See Abraham Lincoln on slavery). By 1863, following the use of black troops, most scholars believe that Lincoln abandoned the idea. Biographer Stephen B. Oates has observed that Lincoln thought it immoral to ask black soldiers to fight for the US and then to remove them to Africa after their military service. Others, such as the historian Michael Lind, believe that as late 1864 or 1865, Lincoln continued to hold out hope for colonization, noting that he allegedly asked Attorney general Edward Bates if the Reverend James Mitchell could stay on as "your assistant or aid in the matter of executing the several acts of Congress relating to the emigration or colonizing of the freed Blacks."[15] Mitchell, a former state director of the ACS in Indiana, had been appointed by Lincoln in 1862 to oversee the government's colonization programs. In his second term as president, on April 11, 1865, Lincoln gave a speech supporting suffrage for blacks.

Criticism and decline of the ACS

Lemuel Haynes, a free black Presbyterian minister at the time of the Society's formation, argued passionately that God's providential plan would eventually defeat slavery and lead to the harmonious integration of the races as equals.[citation needed] Beginning in the 1830s, some abolitionists increasingly attacked the ACS, criticizing colonization as a slaveholders' scheme and the ACS' works as palliative propaganda to soften the continuation of slavery in the United States. The presidents of the ACS tended to be Southerners. The first president of the ACS was Bushrod Washington, the nephew of U.S. President George Washington and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. From 1836-1849 the statesman Henry Clay of Kentucky, a planter and slaveholder, was ACS president.

Three of the reasons the movement never became very successful were the objections raised by free blacks and abolitionists, the scale and costs of moving many people (there were 4 million freedmen in the South after the Civil War), and the difficulty in finding locations willing to accept large numbers of black newcomers (no African tribe accepted newcomers[citation needed], so the society relied on creating settlements at small colonial ports).

Library of Congress

In 1913 and again at its formal dissolution in 1964, the Society donated its records to the U.S. Library of Congress. The material contains a wealth of information about the foundation of the society, its role in establishing Liberia, efforts to manage and defend the colony, fund-raising, recruitment of settlers, conditions for black citizens of the American South, and the way in which black settlers built and led the new nation.

See also

- Atlantic slave trade

- Colonization Societies

- History of Liberia

- Lott Carey, of Richmond, Virginia, the first American missionary to Liberia

- Loring D. Dewey, agent of ACS who promoted free blacks' emigration to Haiti in the 1820s

- Maryland State Colonization Society

- Slavery in the United States

- Samuel Wilkeson, in 1838, he became general agent of the Society

Sources

- Allen, Richard, "Freedom's prophet", NYU Press, New York, 2008.

- Barton, Seth, "Remarks on the colonization of the western coast of Africa", Cornell University Library, 1850.

- Boley, G.E. Saigbe, "Liberia: The Rise and Fall of the First Republic", Macmillan Publishers, London, 1983.

- Burin, Eric. Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society. University Press of Florida, 2005.

- Cassell, Dr. C. Abayomi, "Liberia: History of the First African Republic", Fountainhead Publishers Inc., New York, 1970.

- Egerton, Douglas R. Charles Fenton Mercer and the Trial of National Conservatism. University Press of Mississippi, 1989.

- Jenkins, David, "Black Zion: The Return of Afro-Americans and West Indians to Africa", Wildwood House, London, 1975.

- Johnson, Charles S., "Bitter Canaan: The Story of the Negro Republic", Transaction Books, New Brunswick, NJ, 1987.

- Liebenow, J. Gus, "Liberia: The Evolution of Privilege", Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1969.

- Miller, Floyd J., "The Search for a Black Nationality: Black Emigration and Colonization, 1787–1863", University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, 1975.

- Thomas, Lamont D. Paul Cuffe: Black Entrepreneur and Pan-Africanist (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988)

- West, Richard, "Back to Africa", Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc., New York, 1970.

- Yarema, Allan E., "American Colonization Society: an avenue to freedom?", University Press of America, 2006.

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress.- ^ Bateman, Graham; Victoria Egan, Fiona Gold, and Philip Gardner (2000). Encyclopedia of World Geography. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 161. ISBN 1-56619-291-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Background on conflict in Liberia"[dead link], Friends Committee on National Legislation, 30 July 2003

- ^ a b "Colonization: Thirty-Sixth Anniversary of the American Colonization Society", New York Times, 19 January 1853

- ^ Bateman, Graham; Victoria Egan, Fiona Gold, and Philip Gardner (2000). Encyclopedia of World Geography. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 161. ISBN 1-56619-291-9.

- ^ Thomas, Lamont D. Paul Cuffe: Black Entrepreneur and Pan-Africanist (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988) pp. 46-56, 93-106

- ^ Loc.gov

- ^ Introduction - Social Aspects of the Civil War

- ^ Barton (1850), pg. 9

- ^ Newman (2008), pg. 203."Massachusetts politician Edward Everett spoke for many Northern colonizationists when he supported colonizing free blacks, whom he described as vagabonds, criminals, and a drain on Northern society."

- ^ Yarema (2006), pp. 26-27.

Free blacks, according to many Whigs, would never be accepted into white society ... so the only acceptable solution seemed to be emigration to Africa.

"Northern philanthropic groups supported colonization as an effective way to elevate free blacks who migrated to northern states." - ^ Frankie Hutton, “Economic Considerations in the American Colonization Society’s Early Effort to Emigrate Free Blacks to Liberia, 1816-36", The Journal of Negro History (1983)

- ^ Emigration vs. assimilation: the debate in the African American press, 1827-1861 By Kwando Mbiassi Kinshasa (1988). University of Michigan

- ^ a b Maggie Montesinos Sale (1997). The slumbering volcano: American slave ship revolts and the production of rebellious masculinity. p.264. Duke University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8223-1992-6

- ^ Academic.udayton.edu

- ^ Bates to Lincoln, November 30, 1864, Library of Congress[1]

External links

- U.S. Library of Congress exhibition, based on materials deposited by the ACS.

- A View of Liberian History and Government: A critical view of the ACS

- PBS article

- Article at Slavery in the North

- The American Colonization Society

- Records of the American Colonization Society from the U.S. Library of Congress

- The Liberator Files, Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator - excerpts concerning Colonization / Anti-Colonization original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

Categories:- History of racism in the United States

- Colonialism

- 1816 establishments in the United States

- 1964 disestablishments

- African American history

- African American repatriation organizations

- 19th century in Liberia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.