- History of Somalia

-

History of Somalia

Ancient Laas Geel Culture Kingdom of Punt Malaoites · Oponeans Mosyllonians Medieval Kingdom of Ifat Warsangali Sultanate Adal Sultanate Ajuuraan Empire Early modern Gobroon Dynasty Majeerteen Sultanate Modern Sultanate of Hobyo Dervish State Italian Somaliland British Somaliland Independence Aden Adde Administration Shermarke Administration Communist rule Recent History Somali maritime history Somalia (Somali: Soomaaliya; Arabic: الصومال aṣ-Ṣūmāl), officially the Republic of Somalia (Somali: Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliya, Arabic: جمهورية الصومال Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmāl) and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya on its southwest, the Gulf of Aden with Yemen on its north, the Indian Ocean at its east, and Ethiopia to the west.

This article describes its overall history. See Somalia for details of the country as it is today.

Contents

Prehistory

Somalia has been inhabited since the Palaeolithic period. Cave paintings said to date back as far as 9000 BC have been found in northern Somalia.[1] The most famous of these is the Laas Geel complex, which contains some of the earliest known rock art on the African continent. Inscriptions have been found beneath each of the rock paintings, but archaeologists have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing.[2] During the Stone age, the Doian culture and the Hargeisan culture flourished here with their respective industries and factories.[3]

The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to 4th millennium BC.[4] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in northern Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in palaeolithic times between the East and the West[5]

Ancient

Main articles: Architecture of Somalia and Somali maritime historyAncient pyramidical structures, tombs, ruined cities and stone walls such as the Wargaade Wall littered in Somalia are evidence of an ancient sophisticated civilization that once thrived in the Somali peninsula.[6] The findings of archaeological excavations and research in Somalia show that this ancient civilization had had an ancient writing system that remains undeciphered[7] and enjoyed a lucrative trading relationship with Ancient Egypt and Mycenean Greece since at least the second millennium BC, which supports the view of Somalia being the ancient Kingdom of Punt. The Puntites "traded not only in their own produce of incense, ebony and short-horned cattle, but also in goods from other neighbouring regions, including gold, ivory and animal skins."[8] According to the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, the Land of Punt was ruled at that time by King Parahu and Queen Ati.[9]

Herodotus spoke of the Macrobians, an ancient people and kingdom postulated to have been located on the Somali peninsula[10][11] during the 1st millennium BC. They are mentioned as being a nation of people that had mastered longevity with the average Macrobian living till the age of 120. They were said to be the "Tallest and Handsomest of all men".[12] The Persian Emperor Cambyses II upon conquering Ancient Egypt sent ambassadors to Macrobia bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission, but instead the Macrobian ruler replied with a challenge for the Persian ruler in the form of an unstrung bow, that if the Persians could manage to string, they would have the right to invade his country, but until then they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.[12]

Ancient Somalis domesticated the camel somewhere between the third millennium and second millennium BC from where it spread to Ancient Egypt and North Africa.[13] In the classical period, the city states of Mosylon, Opone, Malao, Sarapion, Mundus, and Tabae in Somalia developed a lucrative trade network connecting with merchants from Phoenicia, Ptolemic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea and the Roman Empire They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo. After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab merchants barred Indian merchants from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula because of the nearby Roman presence. However, they continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from any Roman threat or spies. The reason for barring Indian ships from entering the wealthy Arabian port cities was to protect and hide the exploitative trade practices of the Somali and Arab merchants in the extremely lucrative ancient Red Sea-Mediterranean Sea commerce. The Indian merchants for centuries brought large quantities of cinnamon from Ceylon and the Far East to Somalia and Arabia. This is said to have been one of the most remarkable secrets of the Red Sea port cities of Arabia and the Horn of Africa in their trade with the Roman and Greek world.[14] The Romans and Greeks believed the source of cinnamon to have been the Somali peninsula but in reality, the highly valued product was brought to Somalia by way of Indian ships.[15][16][17] Through Somali and Arab traders, Indian/Chinese cinnamon was also exported for far higher prices to North Africa, the Near East and Europe, which made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue maker, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands the large quantities were shipped across the ancient sea and land routes.[citation needed]

Medieval

Main articles: Adal Sultanate, Ajuuraan State, and Warsangali SultanateThe history of Islam in the Horn of Africa is as old as the religion itself.[18] The early persecuted Muslims fled to the Axumite port city of Zeila in present-day Somalia to seek protection from the Quraysh at the court of the Axumite Emperor in modern Ethiopia. Some of the Muslims that were granted protection are said to have settled in several parts of the Horn of Africa to promote the religion.[19] The victory of the Muslims over the Quraysh in the 7th century had a significant impact on Somalia's merchants and sailors, as their Arab trading partners had now all adopted Islam and the major trading routes in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea now became part of a trade network known as Pax Islamica. Through commerce, Islam spread amongst the Somali population in the coastal cities of Somalia. Instability in the Arabian peninsula saw several migrations of Arab families to Somalia's coastal cities, who then contributed another significant element to the growing popularity of Islam in the Somali peninsula.[20]

13th century Fakr ad-Din mosque

13th century Fakr ad-Din mosque

For many years, Mogadishu stood as the pre-eminent city in the بلاد البربر Bilad-ul-Barbar ("Land of the Berbers"), which was the medieval Arabic term for the Horn of Africa. This may be linked to the fact that the Somalis are the ancestors of the Berbers that inhabited the Maghreb.[21][22][23]

Mogadishu became the center of Islam on the East African coast, and Somali merchants established a colony in Mozambique to extract gold from the Monomopatan mines in Sofala.[24] In northern Somalia, Adal was in its early stages a small trading community established by the newly-converted Horn of Africa Muslim merchants, who were predominantly Somali according to Arab and Somali chronicles. The century between 1150 and 1250 marked a decisive turn in the role of Islam in Somali history. Following his visit to the city, the 12th century Syrian historian Yaqut al-Hamawi wrote that Mogadishu was inhabited by dark-skinned Berbers, the ancestors of the modern Somalis.[25][26] The Adal Sultanate was now a center of a commercial empire stretching from Cape Guardafui to Hadiya. The Adalites then came under the influence of the expanding Horn African Kingdom of Ifat, and prospered under its patronage. The capital of the Ifat was Zeila, situated in northern present-day Somalia, from where the Ifat army marched to conquer the ancient Kingdom of Shoa in 1270.

The Muslim and Christian communities of modern Somalia and Ethiopia enjoyed friendly relations for centuries. The conquest of Shoa ignited a rivalry for supremacy between the Christian Solomonids and the Muslim Ifatites which resulted in several devastating wars and ultimately ended in a Solomonic victory over the Kingdom of Ifat. Parts of northwestern Somalia came under the rule of the Solomonids in medieval times, especially during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344). In 1403 or 1415 (under Emperor Dawit I or Emperor Yeshaq I, respectively) measures were taken against the Muslim Sultanate of Adal. The Emperor eventually captured King Sa'ad ad-Din II in Zeila and had him executed. The Walashma Chronicle, however, records the date as 1415, which would make the Ethiopian victor Emperor Yeshaq I. After the war, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali". Sa'ad ad-Din II's family was subsequently given safe haven at the court of the King of Yemen, where his sons regrouped and planned their revenge on the Solomonids.

Almnara Tower Somalia.

Almnara Tower Somalia.

The oldest son Sabr ad-Din II build a new capital eastwards of Zeila known as Dakkar and began referring to himself as the King of Adal. He continued the war against the Solomonic Empire. Despite his army's smaller size, he was able to defeat the Solomonids at the battles of Serjan and Zikr Amhara and consequently pillaged the surrounding areas. Many similar battles were fought between the Adalites and the Solomonids with both sides achieving victory and suffering defeat but ultimately Sultan Sabr ad-Din II successfully managed to drive the Solomonic army out of Adal territory. He died a natural death and was succeeded by his brother Mansur ad-Din who invaded the capital and royal seat of the Solomonic Empire and drove Emperor Dawit II to Yedaya where according to al-Maqrizi, Sultan Mansur destroyed a Solomonic army and killed the Emperor. He then advanced to the mountains of Mokha where he encountered a 30 000 strong Solomonic army. The Adalite soldiers surrounded their enemies and for two months besieged the trapped Solomonic soldiers until a truce was declared in Mansur's favour.

Later on in the campaign, the Adalites were struck by a catastrophe when Sultan Mansur and his brother Muhammad were captured in battle by the Solomonids. Mansur was immediately succeeded by the youngest brother of the family Jamal ad-Din II. Sultan Jamal reorganized the army into a formidable force and defeated the Solomonic armies at Bale,Yedeya and Jazja. Emperor Yeshaq responded by gathering a large army and invaded the cities of Yedeya and Jazja but was repulsed by the soldiers of Jamal. Following this success, Jamal organized another successful attack against the Solomonic forces and inflicted heavy casualties in what was reportedly the largest Adalite army ever fielded. As a result, Yeshaq was forced to withdraw towards the Blue Nile over the next five months, while Jamal ad Din's forces pursued them and looted much gold on the way, although no engagement ensued.

Ahmed Gurey monument in Mogadishu.

Ahmed Gurey monument in Mogadishu.

After returning home, Jamal sent his brother Ahmad with the Christian battle-expert Harb Jaush to successfully attack the province of Dawaro. Despite his losses, Emperor Yeshaq was still able to continue field armies against Jamal. Sultan Jamal continued to advance further into the Abyssinian heartland. However Jamal upon hearing of Yeshaq's plan to sent several large armies to attack three different areas of Adal, including the capital returned to Adal where he fought the Solomonic forces at Harjai and according to al-Maqrizi this is where the Emperor Yeshaq died in battle. The young Sultan Jamal ad-Din II at the end of his reign had outperformed his brothers and forefathers in the war arena and became the most successful ruler of Adal to date. Within a few years, however, Jamal was assassinated by either disloyal friends or cousins around 1432 or 1433, and was succeeded by his brother Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din. Sultan Badlay continued the campaigns of his younger brother and began several successful expeditions against the Christian empire. He recovered the Kingdom of Bali and began preparations of a major Adalite offensive into the Ethiopian Highlands. He successfully collected funding from surrounding Muslim Kingdoms as far away as the Kingdom of Mogadishu.[27] These ambitious plans however were thrown out the war chamber when King Badlay died during the invasion of Dawaro. He was succeeded by his son Muhammad ibn Badlay who sent envoys to the Sultan of Mamluk Egypt to gather support and arms in the continuing war against the Christian empire. The Adalite ruler Muhammad and the Solomonic ruler Baeda Maryam agreed to a truce and both states in the following decades saw an unprecedent period of peace and stability.

Early modern

Main articles: Dervish State, Gobroon Dynasty, and Sultanate of HobyoSultan Muhammad was succeeded by his son Shams ad Din while Emperor Baeda Maryam was succeeded by his son Eskender. During this time period warfare broke out again between the two states and Emperor Eskender invaded Dakkar where he was stopped by a large Adalite army who destroyed the Solomonic army to such an extent that no further expeditions were carried out for the remaining of Eskender's reign. Adal however continued to raid the Christian empire unabated under the General Mahfuz, the leader of the Adalite war machine who annually invaded the Christian territories. Eskender was succeeded by Emperor Na'od who tried to defend the Christians from General Mahfuz but he too was also killed in battle by the Adalite army in Ifat.

At the turn of the 16th century Adal regrouped and around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed), Adal invaded Ethiopia. Adalite armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia and caused considerable damage on the Highland state. Many historic Churches, manuscripts and settlements were looted and burned during the campaigns.[29] Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama.[30] The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. A Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the Muslims but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Muslim army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which Ahmed Gurey was killed and the war won. Ahmed Gurey's widow married his nephew Nur ibn Mujahid, in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Ahmed Gurey, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia

Barawa city, was an important medieval centre of Somali enterprise.

Barawa city, was an important medieval centre of Somali enterprise.

During the Age of the Ajuuraans, the sultanates and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venetia,[31] Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. Vasco Da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[32] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in India sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbaso also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[33]

Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria[34]), together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[35] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood,[36] Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century[37] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[38] Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between the Asia and Africa[39] and influenced the Chinese language with the Somali language in the process. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani meddling, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[40]

The 16th century Somali-Portuguese wars in East Africa meant that geopolitical tensions would remain high and the increased contact between Somali sailors and Ottoman corsairs worried the Portuguese who send a punitive expedition against Mogadishu under Joao de Sepuvelda, which was unsuccessful.[42] Ottoman-Somali cooperation against the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean reached a high point in the 1580s when Ajuuraan clients of the Somali coastal cities began to symphatize with the Arabs and Swahilis under Portuguese rule and sent an envoy to the Turkish corsair Mir Ali Bey for a joint expedition against the Portuguese. He agreed and was joined by a Somali fleet, which began attacking Portuguese colonies in Southeast Africa.[43] The Somali-Ottoman offensive managed to drive out the Portuguese from several important cities such as Pate, Mombasa and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor sent envoys to India requesting a large Portuguese fleet. This request was answered and it reversed the previous offensive of the Muslims into one of defense. The Portuguese armada managed to re-take most of the lost cities and began punishing their leaders, but they refrained from attacking Mogadishu.[44]

In the early modern period, successor states of the Adal and Ajuuraan empires began to flourish in Somalia. These were the Warsangali Sultanate, the Bari Dynasties and the Gobroon Dynasty. They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

19th century

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started the Golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army came out victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade. He also received presents and had cordial relations with the rulers of neighbouring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu and Yemeni Sultans. Sultan Ibrahim's son Ahmed Yusuf succeeded him and was one of the most important figures in 19th century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast. In northern Somalia, the Gerad Dynasty conducted trade with Yemen and Persia and competed with the merchants of the Bari Dynasty. The Gerads and the Bari Sultans built impressive palaces, castles and fortresses and had close relations with many different empires in the Near East.

Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, leader of the Dervishes.

Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, leader of the Dervishes.

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin conference, European powers began the Scramble for Africa, which inspired the Dervish leader Muhammad Abdullah Hassan to rally support from across the Horn of Africa and begin one of the longest colonial resistance wars ever. In several of his poems and speeches, Hassan emphasized that the British "have destroyed our religion and made our children their children" and that the Christian Ethiopians in league with the British were bent upon plundering the political and religious freedom of the Somali nation. He soon emerged as "a champion of his country's political and religious freedom, defending it against all Christian invaders." Hassan issued a religious ordinance that any Somali national who did not accept the goal of unity of Somalia and would not fight under his leadership would be considered as kafir or gaal. He soon acquired weapons from Ottoman Empire, Sudan, and other Islamic and/or Arabian countries, and appointed ministers and advisers to administer different areas or sectors of Somalia. In addition, Hassan gave a clarion call for Somali unity and independence, in the process organizing his follower-warriors. His Dervish movement had an essentially military character, and the Dervish State was fashioned on the model of a Salihiya brotherhood. It was characterized by a rigid hierarchy and centralization. Though Hassan threatened to drive the Christians into the sea, he committed the first attack by launching his first major military offensive with his 1,500 Dervish equipped with 20 modem rifles on the British soldiers stationed in the region.

He repulsed the British in four expeditions and had relations with the central powers of the Ottomans and the Germans.

20th century

In 1920, the Dervish state collapsed after intensive British aerial bombardments, and Dervish territories were subsequently turned into a protectorate. The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia according to the plan of Fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of Somaliland. Italy had access to these areas under the successive protection treaties, but not direct rule. The Fascist government had direct rule only over the Benadir territory. Given the defeat of the Dervish movement in the early 1920s and the rise of fascism in Europe, on 10 July 1925 Mussolini gave the green light to De Vecchi to start the takeover of the north-eastern sultanates. Everything was to be changed and the treaties abrogated.

Governor De Vecchi's first plan was to disarm the sultanates. But before the plan could be carried out there should be sufficient Italian troops in both sultanates. To make the enforcement of his plan more viable, he began to reconstitute the old Somali police corps, the Corpo Zaptié, as a colonial force.

In preparation for the plan of invasion of the sultanates, the Alula Commissioner, E. Coronaro received orders in April 1924 to carry out a reconnaissance on the territories targeted for invasion. In spite of the forty year Italian relationship with the sultanates, Italy did not have adequate knowledge of the geography. During this time, the Stefanini-Puccioni geological survey was scheduled to take place, so it was a good opportunity for the expedition of Coronaro to join with this.

Coronaro's survey concluded that the Ismaan Sultanate depended on sea traffic, therefore, if this were blocked any resistance which could be mounted came after the invasion of the sultanate would be minimal. As the first stage of the invasion plan Governor De Vecchi ordered the two Sultanates to disarm. The reaction of both sultanates was to object, as they felt the policy was in breach of the protectorate agreements. The pressure engendered by the new development forced the two rival sultanates to settle their differences over Nugaal possession, and form a united front against their common enemy.

Yusuf Ali Kenadid, a prominent Somali anti-imperialist leader and the founder of the Sultanate of Hobyo.

Yusuf Ali Kenadid, a prominent Somali anti-imperialist leader and the founder of the Sultanate of Hobyo.

The Sultanate of Hobyo was different from that of Majeerteen in terms of its geography and the pattern of the territory. It was founded by Yusuf Ali Keenadid in the middle of the 19th century in central Somalia. Its jurisdiction stretched from Ceeldheer through to Dusamareeb in the south-west, from Galladi to Galkacyo in the west, from Jerriiban to Garaad in the north-east, and the Indian Ocean in the east.

By 1 October, De Vecchi's plan was to go into action. The operation to invade Hobyo started in October 1925. Columns of the new Zaptié began to move towards the sultanate. Hobyo, Ceelbuur, Galkayo, and the territory between were completely overrun within a month. Hobyo was transformed from a sultanate into an administrative region. Sultan Yusuf Ali surrendered. Nevertheless, soon suspicions were aroused as Trivulzio, the Hobyo commissioner, reported movement of armed men towards the borders of the sultanate before the takeover and after. Before the Italians could concentrate on the Majeerteen, they were diverted by new setbacks. On 9 November, the Italian fear was realized when a mutiny, led by one of the military chiefs of Sultan Ali Yusuf, Omar Samatar, recaptured El-Buur. Soon the rebellion expanded to the local population. The region went into revolt as El-Dheere also came under the control of Omar Samatar. The Italian forces tried to recapture El-Buur but they were repulsed. On 15 November the Italians retreated to Bud Bud and on the way they were ambushed and suffered heavy casualties.

While a third attempt was in the last stages of preparation, the operation commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Splendorelli, was ambushed between Bud Bud and Buula Barde. He and some of his staff were killed. As a consequence of the death of the commander of the operations and the effect of two failed operations intended to overcome the El-Buur mutiny, the spirit of Italian troops began to wane. The Governor took the situation seriously, and to prevent any more failure he requested two battalions from Eritrea to reinforce his troops, and assumed lead of the operations. Meanwhile, the rebellion was gaining sympathy across the country, and as far afield as Western Somalia.

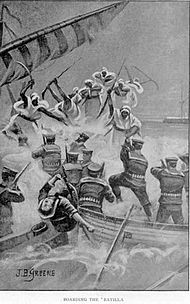

Somali soldiers board a British naval batilla.

Somali soldiers board a British naval batilla.

The fascist government was surprised by the setback in Hobyo. The whole policy of conquest was collapsing under its nose. The El-Buur episode drastically changed the strategy of Italy as it revived memories of the Adwa fiasco when Italy had been defeated by Abyssinia. Furthermore, in the Colonial Ministry in Rome, senior officials distrusted the Governor's ability to deal with the matter. Rome instructed De Vecchi that he was to receive the reinforcement from Eritrea, but that the commander of the two battalions was to temporarily assume the military command of the operations and De Vecchi was to stay in Mogadishu and confine himself to other colonial matters. In the case of any military development, the military commander was to report directly to the Chief of Staff in Rome.

While the situation remained perplexing, De Vecchi moved the deposed sultan to Mogadishu. Fascist Italy was poised to re-conquer the sultanate by whatever means. To maneuver the situation within Hobyo, they even contemplated the idea of reinstating Ali Yusuf. However, the idea was dropped after they became pessimistic about the results.

To undermine the resistance, however, and before the Eritrean reinforcement could arrive, De Vecchi began to instill distrust among the local people by buying the loyalty of some of them. In fact, these tactics had better results than had the military campaign, and the resistance began gradually to wear down. Given the anarchy which would follow, the new policy was a success.

On the military front, on 26 December 1925 Italian troops finally overran El-Buur, and the forces of Omar Samatar were compelled to retreat to Western Somaliland.

By neutralising Hobyo, the fascists could concentrate on the Majeerteen. In early October 1924, E. Coronaro, the new Alula commissioner, presented Boqor (king) Osman with an ultimatum to disarm and surrender. Meanwhile, Italian troops began to pour into the sultanate in anticipation of this operation. While landing at Haafuun and Alula, the sultanate's troops opened fire on them. Fierce fighting ensued and to avoid escalating the conflict and to press the fascist government to revoke their policy, Boqor Osman tried to open a dialogue. However, he failed, and again fighting broke out between the two parties. Following this disturbance, on 7 October the Governor instructed Coronaro to order the Sultan to surrender; to intimidate the people he ordered the seizure of all merchant boats in the Alula area. At Hafun, Arimondi bombarded and destroyed all the boats in the area.

Downtown Mogadishu in 1936. Arba Rucun mosque to the center right.

Downtown Mogadishu in 1936. Arba Rucun mosque to the center right.

On 13 October Coronaro was to meet Boqor Osman at Baargaal to press for his surrender. Under siege already, Boqor Osman was playing for time. However, on 23 October, Boqor Osman sent an angry response to the Governor defying his order. Following this a full scale attack was ordered in November. Baargaal was bombarded and destroyed to the ground. This region was ethnically compact, and was out of range of direct action by the fascist government of Muqdisho. The attempt of the colonizers to suppress the region erupted into explosive confrontation. The Italians were meeting fierce resistance on many fronts. In December 1925, led by the charismatic leader Hersi Boqor, son of Boqor Osman, the sultanate forces drove the Italians out of Hurdia and Haafuun, two strategic coastal towns. Another contingent attacked and destroyed an Italian communications centre at Cape Guardafui, at the tip of the Horn. In retaliation the Bernica and other warships were called on to bombard all main coastal towns of the Majeerteen. After a violent confrontation Italian forces captured Ayl (Eil), which until then had remained in the hands of Hersi Boqor. In response to the unyielding situation, Italy called for reinforcements from their other colonies, notably Eritrea. With their arrival at the closing of 1926, the Italians began to move into the interior where they had not been able to venture since their first seizure of the coastal towns. Their attempt to capture Dharoor Valley was resisted, and ended in failure.

De Vecchi had to reassess his plans as he was being humiliated on many fronts. After one year of exerting full force he could not yet manage to gain a result over the sultanate. In spite of the fact that the Italian navy sealed the sultanate's main coastal entrance, they could not succeed in stopping them from receiving arms and ammunition through it. It was only early 1927 when they finally succeeded in shutting the northern coast of the sultanate, thus cutting arms and ammunition supplies for the Majeerteen. By this time, the balance had tilted to the Italians' side, and in January 1927 they began to attack with a massive force, capturing Iskushuban, at the heart of the Majeerteen. Hersi Boqor unsuccessfully attacked and challenged the Italians at Iskushuban. To demoralise the resistance, ships were ordered to target and bombard the sultanate's coastal towns and villages. In the interior the Italian troops confiscated livestock. By the end of the 1927 the Italians had nearly taken control of the sultanate. Defeated and Hersi Boqor and his top staff were forced to retreat to Ethiopia in order to rebuild the forces. However, they had an epidemic of cholera which frustrated all attempts to recover his force.

With the elimination of the north-eastern sultanates and the breaking of the Benaadir resistance, from this period henceforth, Italian Somaliland was to become a reality.

By 1935, the British were ready to cut their losses in "British Somaliland". The dervishes refused to accept any negotiations. Even after they had been soundly defeated in 1920, sporadic violence continued for the entire duration of British occupation. To make matters worse, Italy invaded and conquered Ethiopia in 1936, whom the British had been using to help their effort to put down the Somali uprisings. Now with Ethiopia unavailable, the British were faced with the option of doing the dirty work themselves, or packing up and looking for friendlier territory.

By this time many thousand Italian immigrants were living in Romanesque villas on extensive plantations in the south. Conditions for natives were very prosperous under fascist Italian rule, and the southern Somalis never violently resisted. It had become obvious then that Italy had won the horn of Africa, and Britain left upon Mussolini's insistence, with little protest.

Meanwhile the French colony had faded to obsolescence with Britain's dwindling control, and it too was neglected. The Italians then enjoyed sole dominance of the entire East African region including recently occupied Ethiopia.

On May 9, 1936, Mussolini proclaimed the creation of the Italian Empire, calling it the "Africa Orientale Italiana" (A.O.I.) and formed by Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somalia. Many investments in infrastructure were made by the Italians in their Empire, like the Strada Imperiale ("imperial road") between Addis Abeba and Mogadishu.

World War II

Italian hegemony of Somalia was short-lived, because of World War II. At the start of the war, Mussolini realized he would have to concentrate his resources primarily on the home front to survive the Allied onslaught.

The Italians conquered the British Somaliland in August 1940, but the British were able to totally reconquer Somalia by 1941. Italian officers organized an Italian guerrilla with Italian colonial troops, that lasted in Somalia from the end of 1941 to spring 1943.

During the war years, Somalia was directly ruled by a British military administration and martial law was in place, especially in the north where bitter memories of past bloodshed still lingered.

Unfortunately these policies were as ill-advised as they were previously. The irregular bandits and militias of the Somali outback received a windfall in weaponry, thanks to the world wide surge in arms production from the war. The Italian settlers and other anti-British elements made sure the rebels got as many guns as they needed to cause trouble. Despite a fresh Somali thorn in their side, the British protectorate lasted until 1949, and actually made some progress in economic development. The British established their capital in the northern city of Hargeisa, and wisely allowed local Muslim judges to try most cases, rather than impose alien British military justice on the populace.

The British allowed almost all the Italians to stay, except for a few too risky for their security, and regularly employed them as civil servants and in the educated professions. The fact that 9 out of 10 of the Italians were loyal to Mussolini, and probably actively spying on the Italian Army's behalf during World War II, was tolerated due to Somalia's relative strategic irrelevance to the larger war effort. Indeed, considering that they were technically citizens of an enemy power, the British lent considerable leeway to the Italian residents, even allowing them to form their own political parties in direct competition with British authority.

Post-War period

After the war, the British gradually relaxed military control of Somalia, and attempted to introduce democracy, and numerous native Somalian political parties sprang into existence, the first being the Somali Youth League (SYL) in 1945. The Potsdam conference was unsure of what to do with Somalia, whether to allow Britain to continue its occupation, to return control to the Italians, who actually had a significant number of people living there, or grant full independence. This question was hotly debated in the Somalian political scene for the next several years. Many wanted outright independence, especially the rural citizens in the west and north. Southerners enjoyed the economic prosperity brought by the Italians, and preferred their leadership. A smaller faction appreciated the British attempt to maintain order.

Ogaden granted to Ethiopia

In 1948 a commission led by representatives of the victorious Allied nations wanted to decide the Somali question once and for all. They made one particular decision, granting Ogaden to Ethiopia, which would spark war decades later. After months of vacillations and eventually turning the debate over to the United Nations, in 1949 it was decided that in recognition of its genuine economic improvements to the country, Italy would retain a nominal trusteeship of Somalia for the next 10 years, after which it would gain full independence. The SYL, Somalia's first and most powerful party, strongly opposed this decision, preferring immediate independence, and would become a source of unrest in the coming years.

Despite the SYL's misgivings the 1950s were something of a golden age for Somalia. With UN aid money pouring in, and experienced Italian administrators who had come to see Somalia as their home, infrastructural and educational development bloomed. This decade passed relatively without incident and was marked by positive growth in virtually all parts of Somali life. As scheduled, in 1960, Somalia was granted independence, and power transferred from the Italian administrators to the well developed Somali political culture.

Independence

Hawo Tako was a remarkable woman who had played a significant role in Somalia's struggle for independence.[1] .

Hawo Tako was a remarkable woman who had played a significant role in Somalia's struggle for independence.[1] .

The freshly independent Somalis loved politics. Every nomad had a radio to listen to political speeches, and although remarkable for an African Muslim country, women were also active participants. There were only mild mumblings from the more conservative sectors of society. Despite this promising start, there were significant underlying problems, most notably the north/south economic divide and the Ogaden issue. Also, long held distrust of Ethiopia and the deeply ingrained belief that Ogaden was rightfully part of Somalia, should have been properly addressed prior to independence. The north and south spoke different languages (English vs Italian respectively) and had different currencies.

Starting in the early 1960s, troubling trends began to emerge when the north started to reject referendums that had won a majority of votes, based on an overwhelming southern favoritism. This came to a head in 1961 when northern paramilitary organizations revolted when placed under southerners' command. The north's second largest political party began openly advocating secession. Attempts to mend these divides with the formation of a Pan-Somalian party were ineffectual; one opportunistic party attempted to unite the bickering regions by rallying them against their common enemy Ethiopia and the cause of reconquering Ogaden. Other nationalistic party platforms included the independence of the northern Kenyan holdings of the Italian colony, from Kenya proper. These regions were largely inhabited by ethnic Somalis who had become accustomed to Italian rule, and were distressed by the different regime they faced in Kenya.

Greater Somalia

Main article: Greater SomaliaSomali people in the Horn of Africa are divided among different territories that were artificially and arbitrarily partitioned by the former Imperial powers. Besides Somalia proper, other historically and almost exclusively Somali-inhabited areas of the Horn of Africa now find themselves administered by neighboring countries, such as the Somali Region in Ethiopia and the North Eastern Province (NFD) in Kenya.[45][46][47][48] Pan Somalism was and is an ideology that advocates the unification of all ethnic Somalis under one flag and one nation. This led to a series of cross border raids by Somali insurgents and violent crackdowns by Ethiopian troops from 1960 to 1964, when open conflict erupted between Ethiopia and Somalia. This lasted a few months until a cease fire was signed in the same year. In the aftermath, Ethiopia and Kenya signed a mutual defense pact to protect their newly acquired territories from the Somali separatists.

Aden Abdullah Osman Daar was the first President of Somalia.

Aden Abdullah Osman Daar was the first President of Somalia.

Although Somalis were, to some extent, politically influenced in the post-war period by the British and the Italians, the socialist parties rejected the European's advice whole cloth, and preferred association with the like-minded Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. By the middle of the 1960s, the Somalis had initiated a formal military relationship with the Soviet Union whereby the Soviets provided extensive material and training to the Somali armed forces in exchange for use of the Somali naval bases. They also had an exchange program in which several hundred soldiers from one country went to the others to train or be trained. As a result of their contact with the Soviet military, many Somali officers gained a distinctly Marxist worldview. China supplied a lot of non-military industrial funding for various projects. Italy, for its part, continued to support its expatriate citizens in the Horn of Africa. The relationship between the rapidly communizing Somali government and the Italian government also remained cordial. The Somalis, however, were increasingly becoming jaded with the United States, which had been sending substantial military aid to their hostile neighbor, Ethiopia, and thanks to incessant anti-Western indoctrination at the hands of their new Russian friends.

By the late 1960s, the Somali democracy that had gotten off to such an enthusiastic start just ten years prior, was beginning to crumble. In the 1967 election, due to a complicated web of clan loyalties, the winner was not properly recognized and instead a new secret vote was taken by already elected National Assemblymen (senators). The central election issue was whether or not to use military force to bring about the long lived dream of pan-Somalism, which would mean war with Ethiopia and Kenya and possibly Djibouti. In 1968 there seemed to be a brief respite from ominous developments when a telecommunications and trade treaty was worked out with Ethiopia, which was very profitable for both countries, and especially for residents on the border who had been living in a de facto state of emergency since the 1964 cease fire.

1969 was a tumultuous year for Somali politics with even more party defections, collusions, betrayals and collaborations than normal. In a major upset, the SYL and its various closely allied supporting parties, which had previously enjoyed a near monopoly of 120 out of 123 seats in the Assembly, saw their power slashed to only 46 seats. This resulted in angry accusations of election fraud from the displaced SYLers, and their remaining members still had the clout to do something about it. Particularly unsettling was that the military was a strong supporter of the SYL, since that party had always been supportive about invading Ethiopia and Kenya, thus giving the military a reason to exist.

Barre regime

Main article: Somali Democratic Republic1969 coup d'etat

The stage was set for a coup d'état, but the event that precipitated the coup was unplanned. On 15 October 1969, a bodyguard killed president Shermarke while prime minister Igaal was out of the country.[50] (The assassin, a member of a lineage said to have been badly treated by the president, was subsequently tried and executed by the revolutionary government.) Igaal returned to Mogadishu to arrange for the selection of a new president by the National Assembly. His choice was, like Shermarke, a member of the Daarood clan-family (Igaal was an Isaaq). Government critics, particularly a group of army officers, saw no hope for improving the country's situation by this means. Critics also saw the process as extremely corrupt with votes for the presidency being actively bid on, the highest offer being 55,000 Somali Shillings (approximately $8,000) per vote by Hagi Musa Bogor. On 21 October 1969, when it became apparent that the assembly would support Igaal's choice, army units, with the cooperation of the police, took over strategic points in Mogadishu and rounded up government officials and other prominent political figures.

Although not regarded as the author of the military takeover, army commander Major General Salad Gabeire Kediye and Mahammad Siad Barre assumed leadership of the officers who deposed the civilian government. The new governing body, the Supreme Revolutionary Council leader Salad Gabeire, installed Siad Barre as its president. The SRC arrested and detained at the presidential palace leading members of the democratic regime, including Igaal. The SRC banned political parties, abolished the National Assembly, and suspended the constitution. The new regime's goals included an end to "tribalism, nepotism, corruption, and misrule". Existing treaties were to be honored, but national liberation movements and Somali unification were to be supported. The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic.

Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC)

The SRC also gave priority to rapid economic and social development through "crash programs", efficient and responsive government, and creation of a standard written form of Somali as the country's single official language. The régime pledged continuance of regional détente in its foreign relations without relinquishing Somali claims to disputed territories.

The SRC's domestic program, known as the First Charter of the Revolution, appeared in 1969. Along with Law Number 1, an enabling instrument promulgated on the day of the military takeover, the First Charter provided the institutional and ideological framework of the new regime. Law Number 1 assigned to the SRC all functions previously performed by the president, the National Assembly, and the Council of Ministers, as well as many duties of the courts. The role of the twenty-five-member military junta was that of an executive committee that made decisions and had responsibility to formulate and execute policy. Actions were based on majority vote, but deliberations rarely were published. SRC members met in specialized committees to oversee government operations in given areas. A subordinate fourteen-man secretariat—the Council of the Secretaries of State (CSS)-- functioned as a cabinet and was responsible for day-to-day government operation, although it lacked political power. The CSS consisted largely of civilians, but until 1974 several key ministries were headed by military officers who were concurrently members of the SRC. Existing legislation from the previous democratic government remained in force unless specifically abrogated by the SRC, usually on the grounds that it was "incompatible… with the spirit of the Revolution." In February 1970, the democratic constitution of 1960, suspended at the time of the coup, was repealed by the SRC under powers conferred by Law Number 1.

Although the SRC monopolized executive and legislative authority, Siad Barre filled a number of executive posts: titular head of state, chairman of the CSS (and thereby head of government), commander in chief of the armed forces, and president of the SRC. His titles were of less importance, however, than was his personal authority, to which most SRC members deferred, and his ability to manipulate the clans.

Military and police officers, including some SRC members, headed government agencies and public institutions to supervise economic development, financial management, trade, communications, and public utilities. Military officers replaced civilian district and regional officials. Meanwhile, civil servants attended reorientation courses that combined professional training with political indoctrination, and those found to be incompetent or politically unreliable were fired. A mass dismissal of civil servants in 1974, however, was dictated in part by economic pressures.

The legal system functioned after the coup, subject to modification. In 1970 special tribunals, the National Security Courts (NSC), were set up as the judicial arm of the SRC. Using a military attorney as prosecutor, the courts operated outside the ordinary legal system as watchdogs against activities considered to be counterrevolutionary. The first cases that the courts dealt with involved Shermaarke's assassination and charges of corruption leveled by the SRC against members of the democratic regime. The NSC subsequently heard cases with and without political content. A uniform civil code introduced in 1973 replaced predecessor laws inherited from the Italians and British and also imposed restrictions on the activities of sharia courts. The new regime subsequently extended the death penalty and prison sentences to individual offenders, formally eliminating collective responsibility through the payment of diyya or blood money.

The SRC also overhauled local government, breaking up the old regions into smaller units as part of a long-range decentralization program intended to destroy the influence of the traditional clan assemblies and, in the government's words, to bring government "closer to the people." Local councils, composed of military administrators and representatives appointed by the SRC, were established under the Ministry of Interior at the regional, district, and village levels to advise the government on local conditions and to expedite its directives. Other institutional innovations included the organization (under Soviet direction) of the National Security Service (NSS), directed initially at halting the flow of professionals and dissidents out of the country and at counteracting attempts to settle disputes among the clans by traditional means. The newly formed Ministry of Information and National Guidance set up local political education bureaus to carry the government's message to the people and used Somalia's print and broadcast media for the "success of the socialist, revolutionary road." A censorship board, appointed by the ministry, tailored information to SRC guidelines.

The SRC took its toughest political stance in the campaign to break down the solidarity of the lineage groups. Tribalism was condemned as the most serious impediment to national unity. Siad Barre denounced clanism in a wider context as a "disease" obstructing development not only in Somalia, but also throughout the Third World. The government meted out prison terms and fines for a broad category of proscribed activities classified as clanism. Traditional headmen, whom the democratic government had paid a stipend, were replaced by reliable local dignitaries known as "peacekeepers" (nabod doan), appointed by Mogadishu to represent government interests. Community identification rather than lineage affiliation was forcefully advocated at orientation centers set up in every district as the foci of local political and social activity. For example, the SRC decreed that all marriage ceremonies should occur at an orientation center. Siad Barre presided over these ceremonies from time to time and contrasted the benefits of socialism to the evils he associated with clanism.

To increase production and control over the nomads, the government resettled 140,000 nomadic pastoralists in farming communities and in coastal towns, where the erstwhile herders were encouraged to engage in agriculture and fishing. By dispersing the nomads and severing their ties with the land to which specific clans made collective claim, the government may also have undercut clan solidarity. In many instances, real improvement in the living conditions of resettled nomads was evident, but despite government efforts to eliminate it, clan consciousness as well as a desire to return to the nomadic life persisted. Concurrent SRC attempts to improve the status of Somali women were unpopular in a traditional Muslim society, despite Siad Barre's argument that such reforms were consistent with Islamic principles.

Siad Barre and scientific socialism

Somalia's adherence to socialism became official on the first anniversary of the military coup when Siad Barre proclaimed that Somalia was a socialist state, despite the fact that the country had no history of class conflict in the Marxist sense. For purposes of Marxist analysis, therefore, clanism was equated with class in a society struggling to liberate itself from distinctions imposed by lineage group affiliation. At the time, Siad Barre explained that the official ideology consisted of three elements: his own conception of community development based on the principle of self-reliance, a form of socialism based on Marxist principles, and Islam. These were subsumed under "scientific socialism," although such a definition was at variance with the Soviet and Chinese models to which reference was frequently made. The theoretical underpinning of the state ideology combined aspects of the Qur'an with the influences of Marx, Lenin, and Mao, but Siad Barre was pragmatic in its application. "Socialism is not a religion," he explained; "It is a political principle" to organize government and manage production. Somalia's alignment with communist states, coupled with its proclaimed adherence to scientific socialism, led to frequent accusations that the country had become a Soviet satellite. For all the rhetoric extolling scientific socialism, however, genuine Marxist sympathies were not deep-rooted in Somalia. But the ideology was acknowledged—partly in view of the country's economic and military dependence on the Soviet Union—as the most convenient peg on which to hang a revolution introduced through a military coup that had supplanted a Western-oriented parliamentary democracy.

More important than Marxist ideology to the popular acceptance of the revolutionary regime in the early 1970s were the personal power of Siad Barre and the image he projected. Styled the "Victorious Leader" (Guulwaadde), Siad Barre fostered the growth of a personality cult. Portraits of him in the company of Marx and Lenin festooned the streets on public occasions. The epigrams, exhortations, and advice of the paternalistic leader who had synthesized Marx with Islam and had found a uniquely Somali path to socialist revolution were widely distributed in Siad Barre's little blue-and-white book. Despite the revolutionary regime's intention to stamp out the clan politics, the government was commonly referred to by the code name MOD. This acronym stood for Marehan (Siad Barre's clan), Ogaden (the clan of Siad Barre's mother), and Dulbahante (the clan of Siad Barre son-in-law Colonel Ahmad Sulaymaan Abdullah, who headed the NSS). These were the three clans whose members formed the government's inner circle. In 1975, for example, ten of the twenty members of the SRC were from the Daarood clan-family, of which these three clans were a part, while the Digil and Rahanweyn, sedentary interriverine clan-families, were totally unrepresented.

The language and literacy issue

One of the principal objectives of the revolutionary regime was the adoption of a standard orthography of the Somali language. Such a system would enable the government to make Somali the country's official language. Since independence Italian and English had served as the languages of administration and instruction in Somalia's schools. All government documents had been published in the two European languages. Indeed, it had been considered necessary that certain civil service posts of national importance be held by two officials, one proficient in English and the other in Italian. During the Husseen and Igaal governments, when a number of English-speaking northerners were put in prominent positions, English had dominated Italian in official circles and had even begun to replace it as a medium of instruction in southern schools. Arabic—or a heavily arabized Somali—also had been widely used in cultural and commercial areas and in Islamic schools and courts. Religious traditionalists and supporters of Somalia's integration into the Arab world had advocated that Arabic be adopted as the official language, with Somali as a vernacular. A few months after independence, the Somali Language Committee was appointed to investigate the best means of writing Somali. The committee considered nine scripts, including Arabic, Latin, and various indigenous scripts. Its report, issued in 1962, favored the Latin script, which the committee regarded as the best suited to represent the phonemic structure of Somali and flexible enough to be adjusted for the dialects. Facility with a Latin system, moreover, offered obvious advantages to those who sought higher education outside the country. Modern printing equipment would also be more easily and reasonably available for Latin type. Existing Somali grammars prepared by foreign scholars, although outdated for modern teaching methods, would give some initial advantage in the preparation of teaching materials. Disagreement had been so intense among opposing factions, however, that no action was taken to adopt a standard script, although successive governments continued to reiterate their intention to resolve the issue.

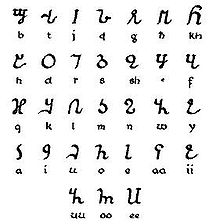

The Borama script for the Somali language

The Borama script for the Somali language

On coming to power, the SRC made clear that it viewed the official use of foreign languages, of which only a relatively small fraction of the population had an adequate working knowledge, as a threat to national unity, contributing to the stratification of society on the basis of language. In 1971 the SRC revived the Somali Language Committee and instructed it to prepare textbooks for schools and adult education programs, a national grammar, and a new Somali dictionary. However, no decision was made at the time concerning the use of a particular script, and each member of the committee worked in the one with which he was familiar. The understanding was that, upon adoption of a standard script, all materials would be immediately transcribed.

On the third anniversary of the 1969 coup, the SRC announced that a Latin script had been adopted as the standard script to be used throughout Somalia beginning January 1, 1973. There were 18 varying scripts brought to the Language Committee. Of these, 11 were new Somali scripts invented by aspiring linguists. Of the remaining seven, 4 were Arabic and 3 Latin. There were over a dozen linguists and Shire Jama Ahmed's Latin version which he already used to print pamphlets won over the council. It is the Somali script or written Af Soomaali used today. The Somali script has 21 consonants and five vowels. As a prerequisite for continued government service, all officials were given three months (later extended to six months) to learn the new script and to become proficient in it. During 1973 educational material written in the standard orthography was introduced in elementary schools and by 1975 was also being used in secondary and higher education.

Somalia's literacy rate was estimated at only 5 percent in 1972. After adopting the new script, the SRC launched a "cultural revolution" aimed at making the entire population literate in two years. The first part of the massive literacy campaign was carried out in a series of three-month sessions in urban and rural sedentary areas and reportedly resulted in several hundred thousand people learning to read and write. As many as 8,000 teachers were recruited, mostly among government employees and members of the armed forces, to conduct the program.

The campaign in settled areas was followed by preparations for a major effort among the nomads that got underway in August 1974. The program in the countryside was carried out by more than 20,000 teachers, half of whom were secondary school students whose classes were suspended for the duration of the school year. The rural program also compelled a privileged class of urban youth to share the hardships of the nomadic pastoralists. Although affected by the onset of a severe drought, the program appeared to have achieved substantial results in the field in a short period of time. Nevertheless, the UN estimate of Somalia's literacy rate in 1990 was only 24 percent.

Creation of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party

One of the SRC's first acts was to prohibit the existence of any political association. Under Soviet pressure to create a communist party structure to replace Somalia's military regime, Siad Barre had announced as early as 1971 the SRC's intention to establish a one-party state. The SRC already had begun organizing what was described as a "vanguard of the revolution" composed of members of a socialist elite drawn from the military and the civilian sectors. The National Public Relations Office (retitled the National Political Office in 1973) was formed to propagate scientific socialism with the support of the Ministry of Information and National Guidance through orientation centers that had been built around the country, generally as local selfhelp projects.

The SRC convened a congress of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) in June 1976 and voted to establish the Supreme Council as the new party's central committee. The council included the nineteen officers who composed the SRC, in addition to civilian advisers, heads of ministries, and other public figures. Civilians accounted for a majority of the Supreme Council's seventy-three members. On July 1, 1976, the SRC dissolved itself, formally vesting power over the government in the SRSP under the direction of the Supreme Council.

In theory the SRSP's creation marked the end of military rule, but in practice real power over the party and the government remained with the small group of military officers who had been most influential in the SRC. Decision-making power resided with the new party's politburo, a select committee of the Supreme Council that was composed of five former SRC members, including Siad Barre and his son-in-law, NSS chief Abdullah. Siad Barre was also secretary general of the SRSP, as well as chairman of the Council of Ministers, which had replaced the CSS in 1981. Military influence in the new government increased with the assignment of former SRC members to additional ministerial posts. The MOD circle also had wide representation on the Supreme Council and in other party organs. Upon the establishment of the SRSP, the National Political Office was abolished; local party leadership assumed its functions.

Ogaden War

Main article: Ogaden WarIn 1977 the Somali president, Siad Barre, was able to muster 35,000 regulars and 15,000 fighters of the Western Somali Liberation Front. His forces began infiltrating into the Ogaden in May–June 1977, and overt warfare began in July. By September 1977 Mogadishu controlled all of the Ogaden and had followed retreating Ethiopian forces into non-Somali regions of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo.

After watching Ethiopian events in 1975-76, the Soviet Union concluded that the revolution would lead to the establishment of an authentic Marxist-Leninist state and that, for geopolitical purposes, it was wise to transfer Soviet interests to Ethiopia. To this end, Moscow secretly promised the Derg military aid on condition that it renounce the alliance with the United States. Mengistu Haile Mariam, believing that the Soviet Union's revolutionary history of national reconstruction was in keeping with Ethiopia's political goals, closed down the U.S. military mission and the communications centre in April 1977. In September, Moscow suspended all military aid to Somalia, and began to openly deliver weapons to its new ally, and reassigned military advisers from Somalia to Ethiopia. This Soviet volte-face also gained Ethiopia important support from North Korea, which trained a People's Militia, and from Cuba and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, which provided infantry, pilots, and armoured units. Somalia renounced the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union expelled all Soviet advisers, broke diplomatic relations with Cuba, and ejected all Soviet personnel from Somalia

By March 1978, Ethiopia and its allies regained control over the Ogaden. Siad Barre proved unable to return the Ogaden to Somali rule, and the people grew restive; in northern Somalia, rebels destroyed administrative centres and took over major towns. Both Ethiopia and Somalia were unable to surmount droughts and famines that afflicted the Horn during the 1980s. In 1988 Siad and Mengistu agreed to withdraw their armies from further confrontation in the Ogaden.

Somalia, 1980-90

Repression

Faced with shrinking popularity and an armed and organized domestic resistance, Siad Barre unleashed a reign of terror against the Majeerteen, the Hawiye, and the Isaaq, carried out by the Red Berets (Duub Cas), a special unit recruited from the president's Marehan clansmen. Thus, by the beginning of 1986, Siad Barre's grip on power seemed secure, despite the host of problems facing the regime. The president received a severe blow from an unexpected quarter, however. On the evening of May 23, he was severely injured in an automobile accident. Astonishingly, although at the time he was in his early seventies and suffered from chronic diabetes, Siad Barre recovered sufficiently to resume the reins of government following a month's recuperation. But the accident unleashed a power struggle among senior army commandants, elements of the president's Marehan clan, and related factions, whose infighting practically brought the country to a standstill. Broadly, two groups contended for power: a constitutional faction and a clan faction. The constitutional faction was led by the senior vice president, Brigadier General Mahammad Ali Samantar; the second vice president, Major General Husseen Kulmiye; and generals Ahmad Sulaymaan Abdullah and Ahmad Mahamuud Faarah. The four, together with president Siad Barre, constituted the politburo of the SRSP.

Opposed to the constitutional group were elements from the president's Marehan clan, especially members of his immediate family, including his brother, Abdirahmaan Jaama Barre; the president's son, Colonel Masleh Siad, and the formidable Mama Khadiija, Siad Barre's senior wife. By some accounts, Mama Khadiija ran her own intelligence network, had well-placed political contacts, and oversaw a large group who had prospered under her patronage.

In November 1986, the dreaded Red Berets unleashed a campaign of terror and intimidation on a frightened citizenry. Meanwhile, the ministries atrophied and the army's officer corps was purged of competent career officers on suspicion of insufficient loyalty to the president. In addition, ministers and bureaucrats plundered what was left of the national treasury after it had been repeatedly skimmed by the top family.

The same month, the SRSP held its third congress. The Central Committee was reshuffled and the president was nominated as the only candidate for another seven-year term. Thus, with a weak opposition divided along clan lines, which he skillfully exploited, Siad Barre seemed invulnerable well into 1988. The regime might have lingered indefinitely but for the wholesale disaffection engendered by the genocidal policies carried out against important lineages of Somali kinship groupings. These actions were waged first against the Majeerteen clan (of the Darod clan-family), then against the Isaaq clans of the north, and finally against the Hawiye, who occupied the strategic central area of the country, which included the capital. The disaffection of the Hawiye and their subsequent organized armed resistance eventually caused the regime's downfall.

Somali Civil War

Main article: Somali Civil WarWith worsening conditions in Somalia, rebels of the United Somali Congress (USC) led by Mohamed Farrah Aidid attacked Mogadishu and on January 26, 1991, Barre's government was overthrown.

In May 1991, the northernwestern Somaliland region of Somalia declared its independence. This Isaaq-dominated governing zone is not recognized by any major international organization or country, although it has remained more stable and certainly more peaceful than the rest of Somalia, neighboring Puntland notwithstanding.[51][52]

UN Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on December 3, 1992, which approved a coalition of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States to form UNITAF, tasked with ensuring humanitarian aid being distributed and peace being established in Somalia until the humanitarian efforts were transferred to the UN. The UN humanitarian troops landed in 1993 and started a two-year effort (primarily in the south), known as UNOSOM II, to alleviate famine conditions.

Many Somalis opposed the foreign presence. In October, several gun battles in Mogadishu between local gunmen and peacekeepers resulted in the death of 24 Pakistanis and 19 US soldiers (total US deaths were 31). Most of the Americans were killed in the Battle of Mogadishu. The incident later became the basis for the book and movie Black Hawk Down. The UN withdrew on March 3, 1995, having suffered more significant casualties. Order in Somalia still has not been restored.

Yet again another secession from Somalia took place in the northeastern region. The self-proclaimed state took the name Puntland after declaring "temporary" independence in 1998, with the intention that it would participate in any Somali reconciliation to form a new central government.

A third secession occurred in 1998 with the declaration of the state of Jubaland. The territory of Jubaland is now encompassed by the state of Southwestern Somalia and its status is unclear.

A fourth self-proclaimed entity led by the Rahanweyn Resistance Army (RRA) was set up in 1999, along the lines of the Puntland. That "temporary" secession was reasserted in 2002. This led to the autonomy of Southwestern Somalia. The RRA had originally set up an autonomous administration over the Bay and Bakool regions of south and central Somalia in 1999.

Recent history

Main articles: History of Somalia (1991-2006), Transitional Federal Government, Islamic Courts Union, Harakat al-Shabaab Mujahideen, War in Somalia (2006–2009), and War in Somalia (2009–)The various Somali militias had at that point developed into security agencies for hire. Due to that development, security had much improved and an economic rebound occurred. Somalia was then arguably partly in a situation where all services were provided by private ventures. According to the CIA, Somalia's telecommunication firms provide wireless services in most major cities and offer the lowest international call rates on the continent.

In 2000, Abdiqasim Salad Hassan was selected to lead the Transitional National Government (TNG).

Flag of the Islamic Courts Union.

Flag of the Islamic Courts Union.

This was followed in 2004 by the establishment of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of the Republic of Somalia, the most recent attempt to restore national institutions to the nation after the 1991 collapse of the Barre regime and the ensuing civil war. On October 10, 2004, Somali parliament members elected Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, the former President of Puntland, to be the next president and head of the TFG. The other institutions adopted at this time were the Transitional Federal Charter and the selection of a 275-member Transitional Federal Parliament.

Though internationally recognized, the TFG's support in Somalia was waning until the United States-backed 2006 intervention by the Ethiopian military, which helped drive out the rival Islamic Courts Union (ICU) in Mogadishu and solidify the TFG's rule.[53] Following this defeat, the ICU splintered into several different factions. Some of the more radical elements, including Al-Shabaab, regrouped to continue their insurgency against the TFG and oppose the Ethiopian military's presence in Somalia. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in both central and southern Somalia. At the end of 2008, the group had captured Baidoa but not Mogadishu. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other militias had managed to force the Ethiopian troops to withdraw from the country, leaving behind an underequipped African Union (AU) peacekeeping force.[54]

Over the next few months, a new President was elected from amongst the more moderate Islamists, and the Transitional Federal Government, with the help of a small team of African Union troops, began a counteroffensive in February 2009 to retake control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its control of southern Somalia, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union and other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia. Furthermore, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main Islamist groups in opposition, began to fight amongst themselves in mid 2009.[55]

As a truce, in March 2009, Somalia's newly established coalition government announced that it would implement shari'a as the nation's official judicial system.[56]

Timelines

Ancient

-

- c. 2350 BC: Ancient Egyptians establish trade with the Land of Punt[57]

- 1st century AD: City States on the Somali coast are active in commerce trading with Greek, and later Roman merchants.[58]

Muslim era

-

- 700 - 1000 AD: City States in Somalia trade with Arab merchants and adopt Islam

- 1300 - 1400 AD: Mogadishu and other prosperous Somali city-states are visited by Ibn Battuta and Zheng he

- 1500 - 1660: the rise and fall of the Adal Sultanate

- 1528 - 1535: Jihad against Ethiopia led by Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (also called Ahmed Gurey and Ahmed Gran; "the Left-handed")[58]

- 1400 - 1700: the Rise and Fall of the Ajuuraan Empire

- 1800 - 1900: Geledi Sultanate/Hobyo Sultanate

Modern era

-

- 20 July 1887 : British Somaliland protectorate (in the north) subordinated to Aden to 1905.

- 3 August 1889: Benadir Coast Italian Protectorate (in the northeast), (unoccupied until May 1893).

- 1900: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan spearheads a Somali war against foreigners and creates the Dervish State

- 16 March 1905: Italian Somalia (Italian Somaliland) colony (in the northeast and in the south).

- July 1910: Italian Somaliland a crown colony.

- 1920: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (called "the Mad Mullah" by the British) dies and the longest and bloodiest colonial resistance war in Africa ends.

- 15 January 1935: Italian Somalia part of Italian East Africa with Italian Eritrea (and from 1936 Ethiopia).

- 1 June 1936: Part of Italian East Africa (province of Somalia, formed by the merger of the colony and the Ethiopian region of Ogaden; see Ethiopia).

World War II

-

- 18 August 1940: Italian occupation of British Somaliland.

- February 1941: British administration of Italian Somalia.

Independence and Cold War

-

- 1 April 1950: Italian Somalia becomes United Nations trust territory administration and Somalia is promised independence within 10 years.

- 26 June 1960: Independence of British Somalia to reunite with Italian Somalia.

- 1 July 1960: Reunification of British Somalia with Italian Somalia to form the Somali Republic.

- 1 July 1960: First President of Somali National Assembly Hagi Bashir Ismail.

- 1960 - 1967: Presidency of Aden Abdullah Osman Daar

- 1967 - 1969: Presidency of Abdirashid Ali Shermarke; assassinated by one of his own bodyguards.[59]

- 21 October 1969: Somali Democratic Republic

- 1969 - 1991: Mohamed Siad Barre Leader of the Supreme Revolutionary Council rises to power.

- 23 July 1977 - 15 March 1978: Ogaden War

- 1982: 1982 Ethiopian-Somali Border War

See also

Main articles: Outline of Somalia and Index of Somalia-related articles- Adal Sultanate

- Ajuuraan State

- Borama script

- Dervish State

- Gobroon Dynasty

- Greater Somalia

- History of Africa

- Land of Punt

- List of colonial heads of British Somaliland

- List of colonial heads of Italian Somaliland

- List of Presidents of Somalia

- Marehan sultanate

- Members of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC)

- Osmanya script

- Politics of Somalia

- Heads of government of Somalia

- Somali maritime history

- Somali people

- Puntland

- Somaliland

- Sultanate of Hobyo

- Warsangali Sultanate

- Xeer

Notes

- ^ pg 9 - Becoming Somaliland By Mark Bradbury

- ^ Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, Somalia, (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.22

- ^ pg 105 - A History of African archaeology By Peter Robertshaw

- ^ pg 40 - Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia, by Steven A. Brandt World Archaeology © 1988

- ^ Prehistoric Implements from Somaliland by H. W. Seton-Karr pg 183

- ^ The Missionary review of the world - Page 132

- ^ Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London pg 447

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ Breasted 1906-07, pp. 246–295, vol. 1.

- ^ The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveries by James Talboys Wheeler pg 528

- ^ The British Critic, Quarterly Theological Review, And Ecclesiastical Record Volume 11 pg 434

- ^ a b Wheeler pg 526

- ^ Near Eastern archaeology: a reader – By Suzanne Richard pg 120

- ^ pg 258 - The commerce between the Roman Empire and India By Eric Herbert Warmington

- ^ pg 28 - Foreign trade and economic development in Africa: a historical perspective By Solomon Daniel Neumark

- ^ pg 186 - The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India