- Battle of San Juan Hill

-

Battle of San Juan Hill Part of the Spanish–American War

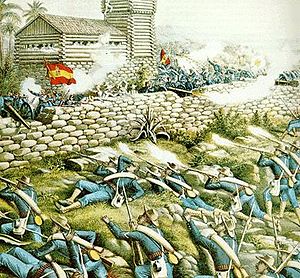

Detail from Charge of the 24th and 25th Colored Infantry at San Juan Hill, July 2, 1898 .Date July 1, 1898 Location near Santiago, Cuba

20°01′15″N 75°47′46″W / 20.0209106°N 75.7961154°WResult U.S./Cuban victory[1] Belligerents  United States

United States

Republic of Cuba

Republic of Cuba Kingdom of Spain

Kingdom of SpainCommanders and leaders  William Rufus Shafter

William Rufus Shafter

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Arsenio Linares

Arsenio LinaresStrength 15,000 infantry

4,000 guerrilleros

12 field guns

4 Gatling guns800 infantry

5 field gunsCasualties and losses 205 dead

1,180 wounded58 dead

170 wounded

39 capturedSpanish-American War and Cuban War of Independence: Cuban Campaign, 18981st Cardenas - 2nd Cardenas - 3rd Cárdenas –1st Cienfuegos – USS Merrimac –Guantánamo Bay – Fort Toro - 2nd Cienfuegos - Las Guasimas – 1st Manzanillo – Tayacoba – Aguadores – El Caney – San Juan Hill – 2nd Manzanillo – Aguacate – 1st Santiago – 2nd Santiago – 3rd Manzanillo – Nipe Bay – Manimani - 4th ManzanilloThe Battle of San Juan Hill (July 1, 1898), also known as the battle for the San Juan Heights, was a decisive battle of the Spanish-American War. The San Juan heights was a north-south running elevation about two kilometers east of Santiago de Cuba. The names San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill were names given by the Americans. This fight for the heights was the bloodiest and most famous battle of the War. It was also the location of the greatest victory for the Rough Riders as claimed by the press and its new commander, the future Vice-President and later President, Theodore Roosevelt was (posthumously) awarded the Medal of Honor in 2001 for his actions in Cuba.[2] Overlooked then by the American Press, much of the heaviest fighting was done by African-American troops.[3]

Contents

Background

The post-battle names of San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill, 760 Spanish Army regular troops were ordered to hold the "San Juan heights" against an American offensive on July 1, 1898. For unclear reasons, Spanish General Arsenio Linares failed to reinforce this position, choosing to hold nearly 10,000 Spanish reserves in the city of Santiago.

Spanish hilltop entrenchments, while typically well-concealed, were not all correctly positioned for plunging fire, making return fire at the advancing Americans more difficult. Most of their fortifications and trench lines were laid out along the geographic (actual) crest of the heights instead of the military crest. This meant that the fire from the Spanish troops would have difficulty hitting the advancing enemy when the attacking Americans reached the defilade at the foot of the heights. Once they began scaling the hill, however, the attackers would be in full view of the defenders, who could engage the Americans with both rifle and artillery fire.[4]

Most Spanish troops were recently arrived conscripts. However, their officers were skilled in fighting Cuban insurgents. The Spanish were also well-equipped with supporting artillery, and all Spanish soldiers were armed with 7 mm Mauser M1893 rifles, a modern repeating bolt action arm with a high rate of fire, and utilizing a high-velocity cartridge and smokeless powder. Spanish artillery units were armed mainly with modern rapid-fire breech-loading cannon, again using smokeless powder.[5]

Likewise, the American regular forces and troopers were armed with bolt-action Krag rifles chambered in the smokeless .30 Army caliber.[6] However, U.S. artillery pieces were of an outmoded design, with a slow rate of fire.[5] They also used less-powerful black powder charges, which limited the effective range of support fire for U.S. troops. A small four-gun detachment of hand-cranked Gatling guns in .30 Army caliber was also present.

General William Rufus Shafter commanded 5th Corps of about 15,000 troops in three divisions. Jacob F. Kent commanded the 1st Division, Henry W. Lawton commanded the 2nd Division, and Joseph Wheeler[7] commanded the dismounted Cavalry Division but was suffering from fever and had to turn over command to General Samuel S. Sumner. Shafter's plans to attack Santiago de Cuba called for Lawton's division to move north and reduce the Spanish stronghold at El Caney, which was to take about two hours then join with the rest of the troops for the attack on the San Juan Heights. The remaining two divisions would move directly against the "San Juan heights" with Sumner in the center and Kent to the south. Shafter was too ill to personally direct the operations and instead set up his headquarters at El Pozo 2 mi (3.2 km) from the heights and communicated through mounted staff officers.

Order of battle

See also: San Juan Hill order of battleU.S.

V Corps – Major General William Rufus Shafter, Corps Executive Officer – Major General Joseph Wheeler (Cavalry Division)

- 1st Division – Brigadier General Jacob Ford Kent

- 1st Brigade – Brigadier General Hamilton S. Hawkins consisted of the 6th and 16th Infantry Regiments, along with the 71st (New York Volunteer) Infantry Regiment

- 2nd Brigade – Colonel E. P. Pearson, consisting of the 2nd, 10th, and 21st U.S. Infantry Regiments

- 3rd Brigade – Colonel Charles A. Wikoff, consisting of the 9th, 13th and 24th (Colored) U.S. Infantry regiments

- Cavalry Division (Dismounted) – Major General Joseph Wheeler, Division Executive Officer Samuel S. Sumner (1st Brigade) was in command of the division when the battle began as General Wheeler was ill. Wheeler returned to the front once the battle was underway.[8]

- 1st Brigade – Brigadier General Samuel S. Sumner, Brigade Executive Officer Colonel Henry K. Carroll (6th Cav), consisted of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry, 6th U.S. Cavalry and 9th U.S. Cavalry.

- 2nd Brigade - Brigadier General Leonard Wood,[9] consisted of the 1st U.S. Cavalry, 10th U.S. Cavalry and 1st Volunteer Cavalry.

The American assault line consisted of the following regiments; From the far left, attacking what later became known as San Juan Hill was the 6th Infantry, the 9th Infantry, the 13th Infantry, the 16th Infantry, the 24th (Colored) Infantry, the 10th (Colored) Cavalry*, with the 3rd Cavalry, 1st Volunteer Cavalry on the far right attacking what became known later as Kettle Hill. *The 10th was the only unit that assaulted both high points on the San Juan heights (Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill).

Spanish

IV Corps – General Arsenio Linares –15th Provisional Battalion –4th Battalion Talavera Peninsular Regiment –1st Battalion San Fernando Regiment –1st Battalion Asia Regiment –1st Battalion Constitutional Regiment –1st Battalion Cuba Regiment –2nd Battalion Cuba Regiment –1st Battalion Simancas Regiment –1st and 2nd Guerrilla Companies –1st Cavalry Regiment

Battle

"Hell's Pocket"

A company from the signal corps ascended in a hot air balloon to reconnoiter the hills. The balloon made for a good target for the Spaniards. Hawkins' brigade had already passed by the new found route and Kent ordered forward the brigade under Colonel Charles A. Wikoff. It was noon by the time Wikoff began heading down the trail, and 30 minutes later he emerged from the woods and was struck by a Mauser bullet. He died as his staff officers carried him to the rear. Next in command was Lt. Col. William S. Worth who assumed command but within five minutes fell wounded. Lt. Col. Emerson Liscom assumed command and within another five minutes received a disabling wound. Lt. Col. Ezra P. Ewers, fourth in command of the brigade, assumed command.

Kent and Sumner lined up for the attack and waited for Lawton's division to arrive from El Caney. Lawton did not arrive as scheduled, and no orders came from either Shafter or Wheeler and the troops waited at the base of the hill plagued by constant Spanish Mauser gunfire in areas dubbed "Hell's Pocket" and/or "Bloody Ford".

San Juan heights

San Juan Hill

In the meantime, Gen. Hamilton Hawkins' 1st Infantry Brigade was preparing to assault San Juan heights. San Juan Hill 20°01′12″N 75°47′54″W / 20.0200185°N 75.7982129°W was the highest of the two hilltops forming San Juan Heights. The southernmost point was most recognizable for the Spanish blockhouse (defensive fort) that dominated the crest. The Cavalry Brigade then moved into position. In open view of the Spanish positions on the heights, the Americans began to suffer casualties from rifle and artillery fire while awaiting orders from General Shafter to take San Juan. As the volume of fire increased, officers began to agitate for action.[4]

The 2nd and 10th Infantry regiments of the 2nd Brigade were ordered by the brigade commander, Col. E. P. Pearson, to advance towards the Spanish lines. Positioned on the far left of the American line, the two regiments moved forward in good order, advanced towards a small knoll on the Spanish right flank, and drove groups of Spanish skirmishers back towards their trenches.

A former brigade staff officer, First Lieutenant Jules Garesche Ord (son of General E.O.C. Ord),[4] officially of the 6th Infantry Regiment, but then temporarily assigned to D Company of the 10th due sick and heat disabled officers in the 5th Corps, made a special request to General Hawkins. "General, if you will order a charge, I will lead it." Hawkins responded "I will not ask for volunteers, I will not give permission and I will not refuse it," he said. "God bless you and good luck!"[4] Lt. Ord then asked the leaders to the right of the 10th Cavalry (i.e. of the 3rd and 1st Volunteers) to "support the regulars" when they would charge the heights. When Ord returned to his assigned unit, he advised his commander of D Troop, Captain John Bigelow, Jr., of his conversation with the General and asking the units on the right to support the regulars. Bigelow gave the honor to sound the advance to Lt. Ord. Ord, with a sword in one hand and a pistol in the other stood up and ordered the advance for his unit. The "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 10th moved out of the trenches and up the hill. Units to the right began moving forward in a ripple effect to support the regulars. To the left of the 10th, a cheer went out from members of the 24th all-black Infantry Regiment and they too moved up toward the top of the heights, accompanied by elements of the 6th Infantry Regiment, including E Company led by Capt. L.W.V. Kennon, as well as units from the 9th, and 13th Infantry Regiments.[4][10] The 16th Infantry followed some distance behind the lead formations, while the 71st (New York Volunteer) infantry regiment, having failed to initially advance with the other regiments, remained at the rear.[11] As the units began their advance up the hill, they became separated, with the battalions of some regiments placed between those of other regiments.

Lt. Ord was among the first to reach the crest of San Juan heights. As the Spanish fled, Lt. Ord began directing supporting fire into the remaining Spanish when he was shot in the throat and mortally wounded. General Hawkins was wounded shortly after.[4] At 13:50, Private Arthur Agnew of the 13th Infantry pulled down the Spanish flag atop the San Juan blockhouse.[12]

General Wood next sent requests for General Kent to send up infantry to strengthen his vulnerable position. When General Wheeler reached the trenches, he ordered breastworks constructed. The Americans' position on San Juan was exposed to artillery fire from within Santiago, and General Shafter feared the vulnerability of the American position on Kettle Hill to counter-attack by Spanish forces. In fact, a Spanish counter-attack was launched late in the afteroon, but was easily beaten back with the aid of supporting Gatling fire from San Juan Hill. Though General Wheeler assured Shafter that the position could be held, Shafter ordered a withdrawal anyway. Before the men on Kettle Hill could withdraw, General Wheeler called aside Generals Kent and Sumner, and reassured them that the line could be held. During the night, the Americans worked at strengthening the lines while awaiting reinforcements.[4]

Kettle Hill

Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill by Frederic Remington. In reality, they assaulted San Juan Heights and the portion later called "Kettle Hill" by the Americans.

The 1st Volunteers (Rough Riders), along with the 3rd Cavalry regiment, began a near simultaneous assault with the regulars of the 10th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) up Kettle Hill, supported by the fire of three Gatling guns commanded by Lt. John H. Parker. Trooper Jesse D. Langdon of the 1st Volunteer Infantry, who accompanied Col. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders in their assault on Kettle Hill, reported:

"We were exposed to the Spanish fire, but there was very little because just before we started, why, the Gatling guns opened up at the bottom of the hill, and everybody yelled, “The Gatlings! The Gatlings!” and away we went. The Gatlings just enfiladed the top of those trenches. We’d never have been able to take Kettle Hill if it hadn’t been for Parker’s Gatling guns."[13]

Under continuous fire, the advance began to slow as troops dropped from heat exhaustion. Officers from the rest of Wood's brigade along with Carrol's brigade began to bunch up under fire. When the regulars punched toward the top of the hill, the units became intermingled. The regulars involved were part of the all-black 10th Cavalry "Buffalo Soldiers". One of the 10th's officers who took part in the attack, Lt. John J. "Black Jack" Pershing, would later reach the highest rank ever held in the United States Army by a living officer—General of the Armies. Pershing later recalled that:

"...the entire command moved forward as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees. White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young manhood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederate or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans."[14]

When the American formations (10th, 3rd & 1st Vol.) reached the summit of Kettle Hill, they fought briefly hand to hand within the Spanish defensive works. After a brief skirmish the Spanish retreated. The first American soldier to reach the crest of Kettle Hill is documented as Sgt. George Berry of the "Negro" 10th Cavalry. Sergeant Berry took his unit colors and that of the 3rd Cavalry to the top of Kettle Hill before the Rough Riders' flag arrived. This is supported in the writings of "Black Jack" Pershing who fought with the 10th on Kettle Hill and who was present when Col. Roosevelt reached the top of Kettle Hill.[4] It appears that politics and racial discrimination led to many myths about the fighting in Cuba where the African-Americans were involved.[3][15]

General Linares's troops on San Juan heights began to fire on the American newly-won position on the crest of Kettle Hill. The Americans in turn began to fire on entrenched Spanish troops on the hills in front of them.[4]

Seeing the 'spontaneous advance' of the 1st Infantry Brigade led by the 10th Cavalry, General Wheeler (having returned to the front) gave the order for Col. Kent to advance with his whole division while he returned to order the 3rd Brigade into the attack. General Kent sent forward the 3rd Infantry Brigade — now effectively commanded by Lt. Col. Ezra P. Ewers[16] — to join the advance of the 1st Infantry Brigade and part of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, who had successfully reached the heights.[4]

Witnessing the assault on San Juan Hill, Col. Roosevelt decided to cross the steep ravine from Kettle Hill to San Juan Hill to support the fighting still going on there. Calling for his men to follow him, he ran forward, only to find just five of the Rough Riders following him (most had not heard his command). Roosevelt returned and gathered together a larger group of his men, leading them down the western slope of Kettle Hill, past a small lagoon, and up the northern extension of San Juan Hill, but the fighting was over for the top of the heights. General Summer intercepted Roosevelt and ordered him back to Kettle Hill immediately to prepare for the expected counterattack. When he returned his men were exhausted and his horse was again spent from the heat. A counterattack directed at Kettle Hill by some 600 Spanish infantry was stopped primarily by the fire of a single ten-barreled .30 Gatling Gun manned by Sergeant Green of the Gatling Gun Detachment, which (according to Spanish officers captured after the attack) killed or wounded all but 40 of the Spanish attackers.[17]

Original title: "Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders at the top of the hill which they captured, Battle of San Juan Hill." US Army victors on Kettle Hill about July 3, 1898 after the battle of "San Juan Hill(s)." Left to right is 3rd US Cavalry, 1st Volunteer Cavalry (Col. Theodore Roosevelt center) and 10th US Cavalry. A second similar picture is often shown cropping out all but the 1st Vol Cav and TR.

Original title: "Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders at the top of the hill which they captured, Battle of San Juan Hill." US Army victors on Kettle Hill about July 3, 1898 after the battle of "San Juan Hill(s)." Left to right is 3rd US Cavalry, 1st Volunteer Cavalry (Col. Theodore Roosevelt center) and 10th US Cavalry. A second similar picture is often shown cropping out all but the 1st Vol Cav and TR.

Gatling supporting fire

During the 2 July assault, V Corps' newly-formed Gatling Gun Detachment participated in the first use by the U.S. Army of machine gun fire for mobile fire support in offensive combat.[18]

Led by First Lt. John Henry Parker, V Army Corps' recently-formed Gatling Gun Detachment was ordered to move forward in support of the U.S. assault. Because U.S. blackpowder artillery pieces lacked the range to reach Spanish positions, Parker's ad hoc Gatling battery of four .30-40, 10-barrelled guns was originally conceived as providing covering fire for the artillery trains. Moving forward on his own initiative, Lt. Parker received a message from his colonel, ordering him to detach one gun to General Shafter's aide, Lt. John D. Miley, then to take the remaining three guns forward "to the best point you can find".[19] Parker set up his three Gatlings approximately 600 yd (550 m) from the San Juan Hill blockhouse and its surrounding trenches, occupied by Spanish regulars; 800 yd (730 m) away was another ridgeline, again with Spanish entrenchments. Being exposed, the Detachment soon came under attack, and quickly lost five men in action to wounds, others to severe heatstroke. Ordinarily, four to six men were required to operate each Gatling gun. Nevertheless, the crews continued to fire back at the Spanish.

Lt. Parker's three rapid-fire[20] Gatlings provided covering fire for U.S. forces assaulting both San Juan and Kettle Hills.[13][21] Equipped with swivel mountings that enabled the gunners to rake Spanish positions, the three guns poured a continuous and demoralizing hail of bullets into the Spanish defensive lines. Witnessing the assault on San Juan Hill, more than one observer from the U.S. side noticed some of the Spanish defenders fleeing their trenches to escape the intense fire.[22][23] The Gatlings continued to fire until Lt. Parker observed Lt. Ferguson of the 13th Infantry waving a white handkerchief as a signal for the battery to cease firing to avoid causing friendly casualties.[24][25] The American assault then broke into a charge about 150 yd (140 m) from the crest of the hill.[19][26]

After the Spanish positions atop San Juan had been taken, two of Lt. Parker's Gatling guns were dragged by mules up the slope to the captured position on San Juan ridge, where both were hurriedly emplaced among a line of skirmishers.[27] As they were setting up the guns, the Spanish commenced a general counterattack on the heights.[28] Though a Spanish counterattack on San Juan was quickly broken up, the Americans on Kettle Hill faced a more serious attack from some 600 Spanish regulars.[28] Ignoring an order from Col. Leonard Wood to reposition one or two of his Gatling guns to the top of Kettle Hill to support the 1st Volunteer and 3rd Cavalry, Parker instead ordered the closest Gatling, manned by Sgt Green, to fire obliquely against 600 enemy soldiers attacking Kettle Hill.[26][28] From a range of 600 yd (550 m), Sgt. Green's Gatling responded, killing all but 40 of the attackers.[19][29][30]

After the counterattack was driven off, Lt. Parker moved to Kettle Hill to view the American positions, where he was soon joined by Sgt. Weigle's Gatling and crew from San Juan, detached to the service of Lt. Miley.[31] Miley (who was primarily interested in inspecting troop positions for General Shafter) had restrained Weigle's crew from opening fire during the entirety of the fighting.[31] Parker then ordered Sgt. Weigle and his crew to emplace their gun on Kettle Hill.[31] This Gatling was used to eliminate Spanish sniper fire against the American defensive positions on Kettle Hill.[31]

Returning to the two Gatlings on San Juan Hill, Lt. Parker had the guns relocated near the road to avoid counterbattery fire.[19][31] Despite this precaution, the guns again came under shellfire from a heavy Spanish 6.3 in (160 mm) gun.[19][31] Parker located the enemy gun and trained the two Gatlings using a powerful set of field glasses. The two Gatlings then opened fire, silencing the Spanish 6.3 in (160 mm) gun at a range of roughly 2,000 yd (1,800 m).[19][31]

Two days later, on the 4th, Parker ordered the three operational guns moved into the battle line around the City of Santiago. The wheels of the Gatling carriages were removed, and the Gatlings, along with two 7 mm Colt-Browning machine guns (a gift from Col. Roosevelt) were placed in breastworks where they could command various sectors of fire. The fourth Gatling was repaired and placed in reserve behind the others. However, it was soon moved to Fort Canosa, where it was used during the siege of Santiago to fire 6,000-7,000 rounds into the city to help force a surrender.[32]

Aftermath

The battle had been a hard one for the Americans, who suffered almost five times as many losses as the Spanish. The Spaniards, meanwhile, had literally fought to the knife, losing a third of their force in casualties but yielding very few prisoners.

Lawton's division, which was supposed to join the fight early on July 1, did not arrive until noon on 2 July, having encountered unexpectedly heavy resistance in the battle of El Caney. The Americans, along with the aid of Cuban insurgents, immediately began the investment of Santiago, which surrendered on July 17.

Theodore Roosevelt, along with the rest of the Rough Riders, achieved considerable fame with the victory. Other soldiers fared less well.Young Jules Garesche Ord never received recognition in the popular press of the day for his actions. The Army turned down requests for a medal for his heroism from his commanding officer and his commanding general.

The large number of U.S. casualties from small-arms fire incurred in the fighting led directly to the Army's decision to update and modernize its small arms arsenal. The .45-70 and M1892 (Krag) Springfield rifles were quickly retired from service in favor of new Mauser-pattern .30-03 (later .30-06) M1903 Springfield rifles, while the remaining .30 Army Gatling guns were replaced in 1909 by the M1909 Benet-Mercie machine gun.

See also

- American Wars

- Spanish Wars

- History of Cuba

- Jules Garesche Ord

- John Bigelow, Jr.

- Lt. John H. Parker

- 10th Cavalry Regiment - Buffalo Soldiers

- Rough Riders

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Nofi, Albert A., The Spanish American War, 1898, 1997.

- Carrasco García, Antonio, En Guerra con Los Estados Unidos: Cuba, 1898, Madrid: 1998.

- Frank N. Schubert "Buffalo Soldiers at San Juan Hill" from a talk in 1998 during the Conference of Army Historians in Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- ^ Konstam, Angus San Juan Hill 1898: America's Emergence as a World Power: 1998, p.77

- ^ Brands, H.W. ed. The Selected Letters of Theodore Roosevelt. (2001), Chapter 13

- ^ a b Anthony L. Powell (1998). "Black Participation in the Spanish-American War". The Spanish-American War Centennial web site. http://www.spanamwar.com/AfroAmericans.htm. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kinevan, Marcos E., Brigadier General, USAF, retired (1998). Frontier Cavalryman, Lieutenant John Bigelow with the Buffalo Soldiers in Texas. Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso. ISBN 0-87404-243-7.

- ^ a b Roosevelt, Theodore, The Rough Riders, Scribner's Magazine, Vol. 25, January–June 1899, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 423

- ^ While the Rough Rider's troopers carried the Krag, each Rough Rider officer was equipped with a .30 Army caliber M1895 Winchester lever action rifle, courtesy of Col. Roosevelt.

- ^ Once the fighting had begun General Wheeler rode to the front becoming the senior ranking officer on the front lines as General Shafter was far to the rear at his headquarters. There he directed parts of Kent's Division and his own Cavalry Division during the attack.

- ^ Longacre, Edward G. A Soldier to the Last: Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler in Blue and Gray: 2006 p.227

- ^ Nofi, Albert The Spanish-American War, 1898, 1997 p.149

- ^ Larned, J.N., History For Ready Reference: Report of General Kent, Vol. 6 (1901), Springfield, MA: C.A. Nichols, pp. 604-605: In his official report, General Kent stated that the 6th, 9th, 13th, 16th, and 24th regiments of infantry participated in the assault on San Juan Hill, and were due equal credit for its capture. The 25th Infantry Regiment (Colored) participated in the Battle of El Caney, and was not present for the attack on San Juan Hill.

- ^ General Kent's Report: His Official Account Of The Three Days' Fighting Around Santiago de Cuba, New York Times, 22 July 1898: Armed with obsolescent M1873 Trapdoor single-shot rifles, and with many of its soldiers ill with malaria, the 71st failed to advance with the lead formations, and played no role in the actual assault.

- ^ General Kent's Report: His Official Account Of The Three Days' Fighting Around Santiago de Cuba, New York Times, 22 July 1898

- ^ a b Jones, V.C., Before The Colors Fade: Last Of The Rough Riders, American Heritage Magazine, August 1969, Vol. 20, Issue 5, p. 26

- ^ Cashin, Herschel V., Under Fire With the 10th U.S. Cavalry, Chicago: American Publishing House (1902) pp. 207-208

- ^ Evan Thomas (2008). "A 'Splendid' War’s Shameful Side. The finale of the Spanish-American war, rooted in misunderstanding and racism, still reverberates.". Newsweek.com. http://www.newsweek.com/id/128987. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ Ewers was the ranking surviving officer of the 3rd Brigade, after Colonel Wikoff, Lt. Col. Worth, and Lt. Col. Liscum had all been killed in action while the Brigade formed for the assault in full view of the Spanish lines atop San Juan Heights.

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), pp. 59-61

- ^ Lt. Parker's use of the Gatling machine gun as offensive fire support was preceded by the U.S. Marines' use of the M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun a month before in their assault on Spanish positions surrounding Guantanamo Bay Harbor

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong, David A., Bullets and Bureaucrats: The Machine Gun and the United States Army 1861-1916, Greenwood Publishing (1982), ISBN 0313230293, 9780313230295, p. 101

- ^ The Model 1895 10-barrelled Gatling Gun was capable of an initial rate of fire of some 800-900 rpm.

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), History of the Gatling Gun Detachment, Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. (1898), pp. 85-89

- ^ Armstrong, David A., Bullets and Bureaucrats: The Machine Gun and the United States Army 1861-1916, Greenwood Publishing (1982), ISBN 0313230293, 9780313230295, p. 104: Capt. Lyman Kennon of the 6th Infantry and Capt. James B. Goe of the 13th Infantry reported that they personally observed Spanish troops running away to escape the Gatling fire.

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006): The three Gatling guns expended a total of 18,000 .30 Army rounds against Spanish troop positions in support of the assault by U.S. forces.

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), History of the Gatling Gun Detachment, Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. (1898), p. 138

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), History of the Gatling Gun Detachment, Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. (1898), pp. 137-138: Col. Egbert, commander of the 6th Infantry assaulting San Juan Hill, stated that his regiment was brought to a momentary halt near the top of San Juan Hill until the cease fire order was given, as the Gatling fire striking the crest and trenchline was so intense.

- ^ a b Tucker, Spencer C., The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO Press (2009), p. 238

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), pp. 58-59: The third gun had broken its pintle pin, and could not be limbered.

- ^ a b c Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), p. 59

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), p. 59: Parker's account is very clear that he never obeyed Col. Wood's order to redeploy his guns to Kettle Hill ("The order to move the guns was disregarded."), instead ordering Sgt. Green's Gatling to fire immediately from its existing position atop San Juan at the Spanish assaulting Kettle Hill.

- ^ Roosevelt, The Rough Riders, p. 568: Speaking of Lt. Parker's contribution to the battle, Roosevelt stated: "I think Parker deserved rather more credit than any other one man in the entire campaign...he had the rare good judgment and foresight to see the possibilities of the machine-guns..He then, by his own exertions, got it to the front and proved that it could do invaluable work on the field of battle, as much in attack as in defence."

- ^ a b c d e f g Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), pp. 60-61

- ^ Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, U.K.: Echo Library (reprinted 2006), p. 68

External links

Categories:- Conflicts in 1898

- Battles of the Spanish–American War

- Theodore Roosevelt

- 1st Division – Brigadier General Jacob Ford Kent

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.