- King Philip's War

-

King Philip's War

Native Americans attacking a garrison houseDate June 1675 – August 1676 Location Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maine Result Colonial Victory Belligerents Wampanoag

Nipmuck

Podunk

Narragansett

NashawayNew England Confederation

Mohegan

PequotCommanders and leaders Metacomet, Metacom, or Pometacom known as "King Philip of Wampanoag",

Canonchet, chief of Narragansett

Awashonks, chief of Sakonnet

Muttawmp, chief of NipmuckGov. Josiah Winslow,

Gov. John Leverett,

Gov. John Winthrop, Jr.,

Captain William Turner,

Captain Benjamin ChurchStrength approx. 3,400 approx. 3,500 Casualties and losses 3,000 600 King Philip's WarBrookfield – Bloody Brook – Springfield – Great Swamp Fight – Lancaster – Sudbury – PeskeompskutKing Philip's War, sometimes called Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, or Metacom's Rebellion,[1] was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day southern New England and English colonists and their Native American allies in 1675–76. The war is named after the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, known to the English as "King Philip".[2] Major Benjamin Church emerged as the Puritan hero of the war; it was his company of Puritan rangers and Native American allies that finally hunted down and killed King Philip on August 12, 1676.[3] The war continued in northern New England (primarily on the Maine frontier) after King Philip was killed, until a treaty was signed at Casco Bay in April 1678.[4]

The war was the single greatest calamity to occur in seventeenth-century Puritan New England. In little over a year, nearly half of the region's towns were destroyed, its economy was all but ruined, and much of its population was killed, including one-tenth of all men available for military service.[5] Proportionately, it was one of the bloodiest and costliest wars in the history of North America.[6] More than half of New England's ninety towns were assaulted by Native American warriors.[7]

King Philip's War was the beginning of the development of a greater American identity, for the trials and tribulations suffered by the colonists gave them a group identity separate and distinct from subjects of the English Crown.[8]

Contents

Background

Plymouth, Massachusetts, was established in 1620 with significant early help from Native Americans, particularly Squanto and Massasoit, Metacomet's father and chief of the Wampanoag tribe. Salem, Boston, and several small towns were established around Massachusetts Bay between 1628 and 1640. The building of towns such as Windsor, Connecticut (est. 1633), Hartford, Connecticut (est. 1636), Springfield, Massachusetts (est. 1636), and Northampton, Massachusetts (est. 1654), on the Connecticut River and towns such as Providence, Rhode Island, on Narragansett Bay (est. 1636), progressively encroached on Native American territories. Prior to King Philip's War, tensions fluctuated between different groups of Native Americans and the colonists, but relations were generally peaceful. As the colonists' small population grew larger over time and the number of their towns increased, the Wampanoag, Nipmuck, Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot, and other small tribes were each treated individually (many were traditional enemies of each other) by the English officials of Rhode Island, Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and New Haven. The New Englanders continued to expand their settlements along the coastal plain and up the Connecticut River valley. By 1675 they had established a few small towns in the interior between Boston and the Connecticut River.

Disease and war

The Native American population throughout the Northeast had been significantly reduced by pandemics of smallpox, spotted fever, typhoid and measles brought by contact with European fishermen, starting in about 1618, two years before the first colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts, had been settled.[9]

Shifting alliances between different Algonkian peoples and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), represented by leaders such as Massasoit, Sassacus, Uncas and Ninigret, and the colonial polities of Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, Rhode Island and Connecticut, negotiated a troubled peace for several decades.

Failure of diplomacy

"King Philip's Seat", a meeting place on Mount Hope (Rhode Island)

"King Philip's Seat", a meeting place on Mount Hope (Rhode Island)

Metacom, known to the English as "King Philip", became Sachem of the Pokanoket and Grand Sachem of the Wampanoag Confederacy after the death in 1662 of his older brother, the Grand Sachem Wamsutta. Well known to the English before his ascension as paramount chief to the Wampanoag, Metacom distrusted the colonists. Wamsutta had been visiting the Marshfield home of Josiah Winslow, the governor of Plymouth Colony, for peaceful negotiations, and suddenly collapsed and died just after leaving the town.

Metacom began negotiating with other Native American tribes against the interests of the Plymouth Colony soon after the deaths of his father Massasoit in 1661, the Plymouth colony's greatest ally, and his brother Wamsutta in 1662. For almost half a century after the colonists' arrival, Massasoit had maintained an uneasy alliance with the English as a source of desired trade goods and a counter-weight to traditional enemies, the Pequot, Narragansett, and the Mohegan. Massasoit's price was colonial incursion into Wampanoag territory as well as English political interference. Maintaining good relations with the English became increasingly difficult, as the English were plying local Natives with alcohol and then obtaining their marks on illegal land sale documents. The colonists' refusal to stop this practice combined with Wamsutta's suspicious death eventually led to Metacom's War.[citation needed]

The war begins

John Sassamon, a Native American Christian convert ("Praying Indian") and early Harvard graduate, translator, and adviser to Metacom, contributed to the outbreak of the war. He spread a rumor to Plymouth Colony officials alleging King Philip's attempts to arrange Native American attacks on widely dispersed colonial settlements. King Philip was brought before a public court to answer to the rumors and after the court admitted it had no proof, it warned him that any other rumors—baseless or otherwise—would be rewarded with further confiscations of Wampanoag land and guns. Not long after, Sassamon was murdered; his body was found in an ice-covered pond (Assawompset Pond), allegedly killed by a few of Philip's Wampanoag, angry at his betrayal.

On the testimony of a Native American witness, the Plymouth Colony officials arrested three Wampanoag, who included one of Metacom's counselors. A jury, among whom were some Indian members, convicted the men of Sassamon's murder; they were hanged on June 8, 1675, at Plymouth. Some Wampanoag believed that both the trial and the court's sentence infringed on Wampanoag sovereignty. On June 20, a band of Pokanoket, possibly without Philip's approval, attacked several isolated homesteads in the small Plymouth colony settlement of Swansea. Laying siege to the town, they destroyed it five days later and killed several inhabitants and others coming to their aid. Officials from Plymouth and Boston responded quickly; on June 28 they sent a military expedition that destroyed the Wampanoag town at Mount Hope (modern Bristol, Rhode Island).

Population

The white population of New England totaled about 80,000 people, including 16,000 men of military age. They lived in 110 towns, of which 64 were in Massachusetts. Many towns had built strong garrison houses for defense, and others had stockades enclosing most of the houses. The region included about 10,500 Indians, including 4000 Narragansett of western Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut, 2400 Nipmuck of central and western Massachusetts, and 2400 combined in the Massachusetts and Pawtucket tribes, living about Massachusetts Bay and extending northwest to Maine. The Wampanoag and Pokanoket of Plymouth and eastern Rhode Island by then numbered fewer than 1000 each. The various tribes, though unconnected in government, spoke dialects of the same Algonquian language, and shared a similar culture.[10]

The war

Early engagements

The war quickly spread, and soon involved the Podunk and Nipmuck tribes. During the summer of 1675, the Native Americans attacked at Middleborough and Dartmouth (July 8), Mendon (July 14), Brookfield (August 2), and Lancaster (August 9). In early September they attacked Deerfield, Hadley, and Northfield (possibly giving rise to the Angel of Hadley legend.)

The New England Confederation declared war on the Native Americans on September 9, 1675. The next colonial expedition was to recover crops from abandoned fields for the coming winter and included almost 100 farmers/militia. They were ambushed and soundly defeated in the Battle of Bloody Brook (near Hadley) on September 18, 1675.[11]

The sack of Springfield

The next attack was organized on October 5, 1675, on the Connecticut River's largest settlement at the time, Springfield, Massachusetts. During the attack, nearly all of Springfield's buildings were burned to the ground., including the town's grist mill. Most of the Springfielders who escaped unharmed took cover at Miles Morgan's house, a resident who had constructed one of Springfield's only fortified blockhouses.[12] An Indian servant who worked for Morgan managed to escape and later alerted the Massachusetts Bay troops under the command of Major Samuel Appleton, who broke through to Springfield and drove off the attackers. Morgan's sons were famous Indian fighters in the territory. The Indians in battle killed his son, Peletiah, in 1675. Springfielders later honored Miles Morgan with a large statue in Court Square, the center of Springfield's urban Metro Center.[12]

The Great Swamp Fight

On November 2, Plymouth Colony governor Josiah Winslow led a combined force of colonial militia against the Narragansett tribe. The Narragansett had not been directly involved in the war, but they had sheltered many of the Wampanoag women and children. Several of their warriors were reported in several Indian raiding parties. The colonists distrusted the tribe and did not understand the various alliances. As the colonial forces went through Rhode Island, they found and burned several Indian towns which had been abandoned by the Narragansett, who had retreated to a massive fort in a swamp. Led by an Indian guide, on December 16, 1675, the colonial force found the Narragansett fort near present-day South Kingstown. A combined force of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut militia numbering about 1,000 men, including about 150 Pequots and Mohicans, attacked the fort. The battle that followed is known as the Great Swamp Fight. It is believed that the militia killed about 300 Narragansett (exact figures are unavailable). The militia burned the fort (occupying over 5 acres (20,000 m2) of land) and destroyed most of the tribe's winter stores.

Many of the warriors and their families escaped into the frozen swamp. Facing a winter with little food and shelter, the entire surviving Narragansett tribe was forced out of quasi-neutrality and joined the fight. The colonists lost many of their officers in this assault: about 70 of their men were killed and nearly 150 more wounded.[13]

Native American victories

Site of "Nine Men's Misery" in Cumberland, Rhode Island, where Captain Pierce's troops were allegedly tortured

Site of "Nine Men's Misery" in Cumberland, Rhode Island, where Captain Pierce's troops were allegedly tortured

Throughout the winter of 1675–76, Native Americans attacked and destroyed more frontier settlements in their effort to expel the English colonists. Attacks were made at Andover, Bridgewater, Chelmsford, Groton, Lancaster, Marlborough, Medfield, Millis, Medford, Portland, Providence, Rehoboth, Scituate, Seekonk, Simsbury, Sudbury, Suffield, Warwick, Weymouth, and Wrentham, including what is modern-day Plainville. The famous account written and published by Mary Rowlandson after the war gives a colonial captive's perspective on it. It was part of a genre known as captivity narratives.[14]

The spring of 1676 marked the high point for the combined tribes when, on March 12, they attacked Plymouth Plantation. Though the town withstood the assault, the natives had demonstrated their ability to penetrate deep into colonial territory. They attacked three more settlements: Longmeadow (near Springfield), Marlborough, and Simsbury were attacked two weeks later. They killed Captain Pierce[15] and a company of Massachusetts soldiers between Pawtucket and the Blackstone's settlement. Several colonial men were allegedly tortured and buried at Nine Men's Misery in Cumberland, as part of the Native Americans' ritual treatment of enemies. The natives burned the abandoned capital of Providence to the ground on March 29. At the same time, a small band of Native Americans infiltrated and burned part of Springfield while the militia was away.

Colonial comeback

The tide of war slowly began to turn in the colonists' favor later in the spring of 1676, as it became a war of attrition; both sides were determined to eliminate the other. The Native Americans had succeeded in driving the colonists back into their larger towns, but the Indians' supplies, nearly always sufficient for only a season or so, were running out. The colony of Rhode Island became an island colony for a time, as the few hundred colonists were driven back to Newport and Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island. The Connecticut River towns with their thousands of acres of cultivated crop land, known as the bread basket of New England, had to manage their crops by working in large armed groups for self protection.[16]:20 Towns such as Springfield, Hatfield, Hadley and Northampton fortified their defenses, reinforced their militias and held their ground, though attacked several times. The small towns of Northfield and Deerfield, and several others, were abandoned as settlers retreated to the larger towns.

Benjamin Church: Father of American ranging

Benjamin Church: Father of American ranging

The towns of the Connecticut colony escaped largely unharmed, although more than 100 militia died in the actions. The colonists were re-supplied by sea from wherever they could buy supplies. The English government did not have sufficient manpower to send any reinforcements. The war ultimately cost the colonists over £100,000—a significant amount of money at a time when most families earned less than £20/yr. Taxes were raised to cover its costs. Over 600 colonial men, women and children were killed, and twelve towns were totally destroyed with many more damaged. Despite this, they eventually emerged victorious. The Native Americans lost many more people. They were dispersed out of New England or put on reservations. They never recovered their former power in New England. The hope of many to integrate Indian and colonial societies was abandoned, as the war and its excesses bred bitter resentment on both sides.

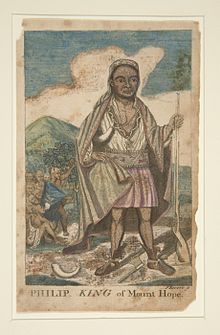

Portrait of King Philip, by Paul Revere, illustration from the 1772 edition of Benjamin Church's The Entertaining History of King Philip's War

Portrait of King Philip, by Paul Revere, illustration from the 1772 edition of Benjamin Church's The Entertaining History of King Philip's War

The Wampanoag and Narragansett hopes for supplies from the French in Canada were not met, except for some small amounts of ammunition obtained in Maine. The colonists allied with the Mohegan and Pequot tribes in Connecticut as well as several Indian groups in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. King Philip and his allies found their forces continually harassed. In January 1675/76 Philip traveled westward to Mohawk territory, seeking, but failing to secure, an alliance. The Mohawks—traditional enemies of many of the warring tribes—proceeded to raid isolated groups of Native Americans, scattering and killing many. Traditional Indian crop-growing areas and fishing places in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut were continually attacked by roving patrols of combined Colonials and friendly Native Americans. The allies had poor luck finding any place to grow more food for the coming winter. Many Native Americans drifted north into Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Canada. Some drifted west into New York and points farther west to avoid their traditional enemies, the Iroquois.

In April 1676 the Narragansett were defeated and their chief, Canonchet, was killed. On May 18, 1676, Captain William Turner of the Massachusetts Militia and a group of about 150 militia volunteers attacked a large fishing camp of Native Americans at Peskeopscut on the Connecticut River (now called Turners Falls, Massachusetts). The colonists claimed they killed 100–200 Native Americans in retaliation for earlier Indian attacks against Deerfield colonist settlements and homesteads, and for disputes over foraging rights on abandoned planting fields. Turner and nearly 40 of the militia were killed during the retreat.[17] With the help of their long-time allies the Mohegans, the colonists won at Hadley on June 12, 1676, and scattered most of the survivors into New Hampshire and points farther north. Later that month, a force of 250 Native Americans was routed near Marlborough. Other forces, often a combined force of colonial volunteers and Indian allies, continued to attack, kill, capture or disperse bands of Narragansett as they tried to return to their traditional locations. The colonists granted amnesty to Native Americans who surrendered and showed they had not participated in the conflict.

Philip's allies began to desert him. By early July, over 400 had surrendered to the colonists, and Philip took refuge in the Assowamset Swamp, below Providence, close to where the war had started. The colonists formed raiding parties of Native Americans and militia. They were allowed to keep the possessions of warring Indians and received a bounty on all captives. Philip was ultimately killed by one of these teams when he was tracked down by colony-allied Native Americans led by Captain Benjamin Church and Captain Josiah Standish of the Plymouth Colony militia at Mt. Hope, Rhode Island. Philip was shot and killed by an Indian named John Alderman on August 12, 1676. Philip was beheaded, then drawn and quartered (a traditional treatment of criminals in this era). His head was displayed in Plymouth for twenty years. The war was nearly over except for a few attacks in Maine that lasted until 1677.

Aftermath

The site of King Philip's death in Miery Swamp on Mount Hope (Rhode Island)

The site of King Philip's death in Miery Swamp on Mount Hope (Rhode Island)

The war in the south largely ended with Metacom's death. Over 600 colonists and 3,000 Native Americans had died, including several hundred native captives who were tried and executed or enslaved and sold in Bermuda.[18] The majority of the dead Native Americans and many of the colonials died as the result of disease, which was typical of all armies in this era. Those sent to Bermuda included Metacom's son (and also, according to Bermudian tradition, his wife). A sizable number of Bermudians today claim ancestry from these exiles. Members of the Sachem's extended family were placed for safekeeping among colonists in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. Other survivors joined western and northern tribes and refugee communities as captives or tribal members. Some of the refugees would return on occasion to southern New England.[19] The Narragansett, Wampanoag, Podunk, Nipmuck, and several smaller bands were virtually eliminated as organized bands,[citation needed] while even the Mohegans were greatly weakened.

Sir Edmund Andros negotiated a treaty with some of the northern Indian bands on April 12, 1678, as he tried to establish his New York-based royal power structure in Maine's fishing industry. Andros was arrested and sent back to England at the start of the Glorious Revolution in 1689. James II, Charles II's younger brother, was forced to vacate the British throne. Sporadic Indian and French raids plagued Maine, New Hampshire and northern Massachusetts for the next 50 years as France encouraged and financed raids on New England settlers. Most of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island was now nearly completely open to New England's continuing settlement, free of interference from the Native Americans. Frontier settlements in New England would face sporadic Indian raids until the French and Indian War (1754–1763) finally drove the French authorities out of North America in 1763.

King Philip's War, for a time, seriously damaged the recently arrived English colonists' prospects in New England. But with their extraordinary population growth rate of about 3% a year (doubling every 25 years), they repaired all the damage, replaced their losses, rebuilt the destroyed towns and continued on with establishing new towns within a few years.

The colonists' defense of New England brought them to the attention of the British royal government which soon tried to exploit them for its own gain—beginning with the revocation of the charter of Massachusetts Bay in 1684 (enforced 1686). At the same time, an Anglican church was established in Boston in 1686, ending the Puritan monopoly on religion in Massachusetts. The legend of Connecticut's Charter Oak stems from the belief that a cavity within the tree was used in late 1687 as a hiding place for the colony's charter as Andros tried unsuccessfully to revoke their charter and take over their militia. In 1690, Plymouth's charter was not renewed, and its inhabitants were forced to join the Massachusetts government. The equally small colony of Rhode Island, with its largely Puritan dissident settlers, maintained its charter – mainly as a counterweight and irritant to Massachusetts. The Massachusetts General Court (the main legislative and judicial body) was brought under nominal British government control, but all members except the Royal Governor and a few of his deputies were elected from the various towns as was the practice.

Nearly all layers of government and church life (except in Rhode Island) remained Puritan, and only a few of the so-called "upper crust" joined the Anglican church. Most New Englanders lived in self-governing towns and attended the Congregational or dissident churches that they had already set up by 1690. New towns, complete with their own militias, were nearly all established by the sons and daughters of the original settlers and were in nearly all cases modeled after these original settlements. The many trials and tribulations between the British crown and British Parliament for the next 100 years made self government not only desirable but relatively easy to continue. The squabbles with the British government would eventually lead to Lexington, Concord and the Battle of Bunker Hill by 1775, a century and four generations later. When the British were forced to evacuate Boston in 1776, only a few thousand of the over 700,000 New Englanders went with them.

King Philip's War joined the Powhatan wars of 1610–14, 1622–32 and 1644–46[20] in Virginia, the Pequot War of 1637 in Connecticut, the Dutch-Indian war of 1643 along the Hudson River[21] and the Iroquois Beaver Wars of 1650[22] in a list of ongoing uprisings and conflicts between various Native American tribes and the French, Dutch, and English colonial settlements of Canada, New York, and New England.

In response to King Philip's War and King William's War (1689–97), many colonists from northeastern Maine relocated to Massachusetts and New Hampshire to avoid Wabanaki Indian raids.[4]

See also

References

- ^ America’s Guardian Myths, op-ed by Susan Faludi, September 7, 2007. New York Times. Accessed September 6, 2007.

- ^ He was also known as Metacom, or Pometacom. King Philip may well have been a name that he adopted, as it was common for Natives to take other names. King Philip had on several occasions signed as such and has been referred to by other natives by that name. Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity, New York: Vintage Books

- ^ Philip Gould. "Reinventing Benjamin Church: Virtue, Citizenship and the History of King Philip's War in Early National America." Journal of the Early Republic, No. 16, Winter 1996. p. 647.

- ^ a b Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, New York: Vintage Books, 2003

- ^ Philip Gould. "Reinventing Benjamin Church: Virtue, Citizenship and the History of King Philip's War in Early National America." Journal of the Early Republic, No. 16, Winter 1996. p. 656. According to a combined estimate of loss of life in Schultz and Tougias' King Philip's War, The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict (based on sources from the Department of Defense, the Bureau of Census, and the work of Colonial historian Francis Jennings), 800 out of 52,000 English colonists (1.5%) and 3,000 out of 20,000 Native Americans (15%) lost their lives due to the war.

- ^ Schultz, Eric B.; Michael J. Touglas (2000). King Philip's War: The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict. W.W. Norton and Co.. pp. 5. ISBN 0-88150-483-1.

- ^ The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut – 1675 King Philip's War

- ^ The Name of War by Harvard University Professor Jill Lepore Lepore, Jill (1998-01-20). The name of war: King Philip's War and the origins of American identity. Knopf. ISBN 0679446869. http://books.google.com/books?id=eHJ0AAAAMAAJ.

- ^ "Epidemics and Pandemics in the U.S."

- ^ Herbert L. Osgood, The American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century (1904) 1: 543 online

- ^ "Battle of Bloody Brook", Connecticut River Homepage, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1997

- ^ a b http://ritaren.tripod.com/miles.html

- ^ Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk – New England in King Philip's War, pp. 130-132

- ^ The Narrative of the Captivity and the Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682), City University of New York

- ^ Findagrave: Captain Pierce

- ^ Phelps, Noah Amherst (1845). History of Simsbury, Granby, and Canton; from 1642 To 1845. Hartford: Press of Case, Tiffany and Burnham.

- ^ Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk – New England in King Philip's War, pp. 200–203

- ^ Worlds rejoined, Cape Cod online, http://www.capecodonline.com/special/tribeslink/worldsrejoined13.htm.

- ^ Spady, James O'Neil. "As if in a Great Darkness: Native American Refugees of the Middle Connecticut River Valley in the Aftermath of King Phillip's War: 1677–1697," Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 23, no. 2 (Summer, 1995), 183–97.

- ^ Swope, Cynthia, "Chief Opechancanough of the Powhatan Confederacy"

- ^ Wick, Steve, "Blood Flows, War Threatens: Violence escalates as a Dutch craftsman is murdered and Indians are massacred", Newsday (archived 2007)

- ^ "Beaver Wars", Ohio History Central

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Easton, John, A Relation of the Indian War, by Mr. Easton, of Rhode Island, 1675 (See link below.)

- Eliot, John, ”Indian Dialogues”: A Study in Cultural Interaction eds. James P. Rhonda and Henry W. Bowden (Greenwood Press, 1980).

- Mather, Increase, A Brief History of the Warr with the Indians in New-England (Boston, 1676; London, 1676). (See link below.)

- ______. Relation of the Troubles Which Have Happened in New England by Reason of the Indians There, from the Year 1614 to the Year 1675 (Kessinger Publishing, [1677] 2003).

- ______. The History of King Philip's War by the Rev. Increase Mather, D.D.; also, a history of the same war, by the Rev. Cotton Mather, D.D.; to which are added an introduction and notes, by Samuel G. Drake(Boston: Samuel G. Drake, 1862).

- ______. "Diary", March, 1675–December, 1676: Together with extracts from another diary by him, 1674–1687 /With introductions and notes, by Samuel A. Green (Cambridge, MA: J. Wilson, [1675–76] 1900).

- Rowlandson, Mary, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: with Related Documents (Bedford/St. Martin's Press, 1997).

- Rowlandson, Mary, The Narrative of the Captivity and the Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682)online edition

- Belmonte, Laura. "Edward Randolph, the Causes and Results of King Philip's War (1675)"

Secondary sources

- Cave, Alfred A. The Pequot War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996).

- Cogley, Richard A. John Eliot's Mission to the Indians before King Philip's War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

- Hall, David. Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

- Kawashima, Yasuhide. Igniting King Philip's War: The John Sassamon Murder Trial (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001).

- Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).

- Mandell, Daniel R. King Philip's War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010) 176 pages

- Norton, Mary Beth. "In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692" (New York: Vintage Books, 2003)

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War (Penguin USA, 2006) ISBN 0-670-03760-5

- Schultz, Eric B. and Michael J. Touglas, King Philip's War: The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict.' New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2000.

- Slotkin, Richard and James K. Folsom. So Dreadful a Judgement: Puritan Responses to King Philip's War. (Middletown, CT: Weysleyan University Press, 1978) ISBN 0-8195-5027-2

- Webb, Stephen Saunders. 1676: The End of American Independence (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995).

External links

- Peters, Paula, "We Missed You", Cape Cod Times, July 14, 2002

- "Edward Randolph on the Causes of the King Philip's War (1685)", rootsweb.com.

- King Phillip's War in Peirce, Ebenezer Weaver, Indian history, biography and genealogy: pertaining to the good sachem Massasoit of the Wampanoag tribe, and his descendants, Z.G. Mitchell, 1878

- Records of Lancaster, Massachusetts, p.324

Categories:- King Philip's War

- Colonial American and Indian wars

- Native American history

- Military history of the Thirteen Colonies

- Native American history of Massachusetts

- Native American history of Connecticut

- Pre-state history of Rhode Island

- Narragansett tribe

- Springfield, Massachusetts

- Providence, Rhode Island

- History of Massachusetts

- 1670s conflicts

- 1670s in the Thirteen Colonies

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.