- Saturday Night Massacre

-

Watergate

Events Timeline

Criminality

1972 presidential election

Watergate burglaries

Watergate tapes

"Saturday Night Massacre"

United States v. Nixon

Inauguration of Gerald FordPeople Richard Nixon

Conspirators

John Dean

John Ehrlichman

H. R. Haldeman

E. Howard Hunt

Egil Krogh

G. Gordon Liddy

Jeb Magruder

John N. Mitchell

"Watergate Seven"Groups "White House Plumbers"

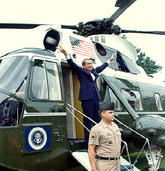

Senate Watergate CommitteeThe "Saturday Night Massacre" was the term given by political commentators[1] to U.S. President Richard Nixon's executive dismissal of independent special prosecutor Archibald Cox, and the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus on October 20, 1973 during the Watergate scandal.[2][3][4]

History

Richardson appointed Cox in May of that year, after having given assurances to the Senate Judiciary Committee that he would appoint an independent counsel to investigate the events surrounding the Watergate break-in of June 17, 1972. Cox subsequently issued a subpoena to President Nixon, asking for copies of taped conversations recorded in the Oval Office and authorized by Nixon as evidence. The president initially refused to comply with the subpoena, but on October 19, 1973, he offered what was later known as the Stennis Compromise—asking U.S. Senator John C. Stennis to review and summarize the tapes for the special prosecutor's office.

Aware that Stennis was famously hard-of-hearing, Cox refused the compromise that same evening and it was believed that there would be a short rest in the legal maneuvering while government offices were closed for the weekend. However, President Nixon acted to dismiss Cox from his office the next night, a Saturday. He contacted Attorney General Richardson and ordered him to fire the special prosecutor. Richardson refused, and instead resigned in protest. Nixon then ordered Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus to fire Cox. He also refused and resigned in protest.[5][6]

Nixon then contacted the Solicitor General, Robert Bork, and ordered him as acting head of the Justice Department to fire Cox. Richardson and Ruckelshaus had both personally assured the congressional committee overseeing the special prosecutor investigation that they would not interfere. However, Bork had made no such assurance to the committee. Though Bork believed Nixon's order to be valid and appropriate, he considered resigning to avoid being "perceived as a man who did the President's bidding to save my job."[7] Nevertheless, after being persuaded by Richardson to stay on to ensure that someone who knew how the Justice Department worked would still be in charge, Bork did comply with Nixon's order after consulting with others, since the President was obviously determined to find someone who would fire Cox. Initially, the White House claimed to have fired Ruckelshaus, but as The Washington Post article written the next day pointed out, "The letter from the President to Bork also said Ruckelshaus resigned."

Congress was infuriated by the act, which was seen as a gross abuse of presidential power. The public sent in an unusually large number of telegrams to both the White House and Congress.[8][9] And following the Saturday Night Massacre, as opposed to August of the same year, an Oliver Quayle poll for NBC News showed that a plurality of American citizens now supported impeachment, with 44% in favor, 43% opposed, and 13% undecided, although with a sampling error of 2 to 3 percent.[10] In the days that followed, numerous resolutions of impeachment against the president were introduced in Congress.

Approximately a month later on Nov. 17, 1973, in response to a number of different issues, including his personal income taxes[11], Pres. Nixon said in a well-remembered speech:

"In all of my years of public life, I have never obstructed justice. And I think, too, that I can say that in my years of public life that I've welcomed this kind of examination, because people have got to know whether or not their President's a crook. Well, I'm not a crook! I've earned everything I've got."[12][13][14]Impact and legacy

Nixon was compelled, however, to allow the appointment of a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who continued the investigation. There was a question whether Jaworski would limit the investigation to only the Watergate burglary itself or follow Cox's lead and also look at broader corrupt activities such as the "White House Plumbers."[15] As it turned out, Jaworski also looked at broader corrupt activities.[16]

While Nixon continued to refuse to turn over actual tapes, he agreed to release transcripts of a large number of them. Nixon cited the fact that any audio pertinent to national security information would have to be redacted from the released tapes. The audio tapes caused further controversy on December 7, when an 18 1/2 minute portion of one tape was found to have been erased. Nixon's personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, said she had accidentally erased the tape by pushing the wrong foot pedal on her tape player while answering the phone. Later forensic analysis determined that the tape had been erased in several segments — at least five, and perhaps as many as nine.[17]

Nixon's presidency would later succumb to mounting pressure resulting from the Watergate scandal and its coverup. In the face of a certain threat of removal from office through impeachment and conviction, Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. The Independent Counsel Act of 1978 was a direct result of the Saturday Night Massacre.

Bork's role, albeit unwilling, in the Saturday Night Massacre would later play a role in his rejection for a Supreme Court associate judgeship in 1987.

References

- ^ Alexander Haig, 85; soldier-statesman managed Nixon resignation

- ^ Our World Fall 1973, Part 4. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OVh4haQ4Ewg&feature=related

- ^ Pres. Nixon's Press Secretary Ron Ziegler reading a statement (audio only), October 20, 1973. http://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675073752_Ronald-Ziegler_Watergate-Case_Richard-Nixon_Saturday-Night-Massacre

- ^ "Nixon Forces Firing of Cox; Richardson, Ruckelshaus Quit". Washingtonpost.com. 1973-10-21. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/articles/102173-2.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ^ Youngstown Vindicator (Ohio), Washington (AP), Nixon Fires Cox; Richardson Quits, Sunday, Oct. 21, 1973, page 1.

- ^ Tri-City Herald (Washington state), Washington (AP), Nixon fires Cox; Richardson quits, Sunday, Oct. 21, 1973, page 1.

- ^ Noble, Kenneth (1987-07-02). "Bork Irked by Emphasis on His Role in Watergate". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/07/02/us/bork-irked-by-emphasis-on-his-role-in-watergate.html. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ The Modesto Bee [California], McClatchy Newspapers Service and UPI, “Record Numbers Jam Western Union” ‘Western Union today reported a record 71,000 telegrams received in its Washington office about the firing [of] Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox in the first 36 hours . . . ’ and “You Can Cheaply Wire (Cable) The White House” ‘ . . . special flat rate for public opinion messages to Washington, DC . . . up to 15 words, can be sent by dialing 1-800 . . . $1.25 charge for the telegram is then billed to the calling person’s telephone number. . . ’, Monday, Oct. 22, 1973, both articles on page A-2.

- ^ Gadsden Times [Alabama], "Impeachment Mail Floods Congress", Oct. 24, 1973, page 2. ' . . . Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., had 270 telegrams for impeachment and about a dozen against it with telephone calls more evenly divided in sentiment. Sen. John G. Tower, R-Tex., reported 275 telegrams against Nixon, 16 for him; . . . '

- ^ Spokane Daily Chronicle, New York (AP), Poll Shows Many for Impeachment, Tuesdays, Oct. 23, 1973, page 14. ‘ . . . shows 44 per cent favored impeaching President Nixon. Forty-three per cent opposed impeachment and 13 per cent were undecided, according to the poll. . . built-in sampling error of 2 to 3 per cent. . . ’

- ^ Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), Frank Cormier, Associated Press Writer, Nixon Counterattacks As The Underdog, November 19, 1973, page 22-A. ’ . . . Nixon acknowledged for the first time he paid nominal federal income taxes -- apparently a total of $1,670 -- during 1970 and 1971. But he said his 1969 taxes were $79,000. . . '

- ^ Discovery Education, 90 second video of what Pres. Nixon said before saying “ . . . I’m not a crook . . . ” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmjMa2hLXpc

- ^ Richard Nixon: Question-and-Answer Session at the Annual Convention of the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, Orlando, Florida. The American Presidency Project.

- ^ Kilpatrick, Carroll, Nixon Tells Editors, 'I'm Not a Crook' Washington Post, November 18, 1973.

- ^ Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “Nixon Hoping Jaworski Will Drop Plumber Probe”, Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, Nov. 6, 1973, page 6.

- ^ The Free Lance-Star [Fredericksburg, Virginia], "Jaworski: In Cox's footsteps", Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, Nov. 19, 1973, page 4.

- ^ Clymer, Adam (May 9, 2003). "National Archives Has Given Up on Filling the Nixon Tape Gap". The New York Times. http://www.webcitation.org/5sPqUFNJO. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

Categories:- American political terms

- Watergate scandal

- 1973 in American politics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.