- Metzora (parsha)

-

Metzora, Metzorah, M’tzora, Mezora, Metsora, or M’tsora (מְּצֹרָע — Hebrew for “one being diseased,” the ninth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parshah) is the 28th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fifth in the book of Leviticus. It constitutes Leviticus 14:1–15:33. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in April.

The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2011, 2014, and 2016), parshah Metzora is read separately. In common years (for example, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2018), parshah Metzora is combined with the previous parshah, Tazria, to help achieve the needed number of weekly readings.

The parshah deals with ritual impurity. It addresses cleansing from tzaraath, houses with an eruptive plague, male genital discharges, and menstruation.

cedar wood

cedar wood

Contents

Summary

Cleansing from skin disease

God told Moses the ritual for cleansing one with a skin disease. (Leviticus 14:1–2.) If the priest saw that the person had healed, the priest would order two live clean birds, cedar wood, crimson stuff, and hyssop. (Leviticus 14:3–4.) The priest would order one of the birds slaughtered over fresh water and would then dip the live bird, the cedar wood, the crimson stuff, and the hyssop in the blood of the slaughtered bird. (Leviticus 14:5–6.) The priest would then sprinkle the blood seven times on the one who was to be cleansed and then set the live bird free. (Leviticus 14:6–7.) The one to be cleansed would then wash his clothes, shave off his hair, bathe in water, and then be clean. (Leviticus 14:8.) On the eighth day after that, the one being cleansed was to present two male lambs, one ewe lamb, choice flour, and oil for the priest to offer. (Leviticus 14:9–13.) The priest was to put some of the blood and the oil on the ridge of the right ear, the right thumb, and the right big toe of the one being cleansed, and then put more of the oil on his head. (Leviticus 14:14–18.) If the one being cleansed was poor, he could bring two turtle doves or pigeons in place of two of the lambs. (Leviticus 14:21–22.)

hyssop (1885 painting by Otto Wilhelm Thomé)

hyssop (1885 painting by Otto Wilhelm Thomé)

Houses with an eruptive plague

God then told Moses and Aaron the ritual for cleansing a house with an eruptive plague. (Leviticus 14:33–34.) The owner was to tell the priest, who was to order the house cleared and then examine it. (Leviticus 14:35–36.) If the plague in the walls was greenish or reddish streaks deep into the wall, the priest was to close the house for seven days. (Leviticus 14:37–38.) If, after seven days, the plague had spread, the priest was to order the stones with the plague to be pulled out and cast outside the city. (Leviticus 14:39–40.) The house was then to be scraped, the stones replaced, and the house replastered. (Leviticus 14:41–42.) If the plague again broke out, the house was to be torn down. (Leviticus 14:43–45.) If the plague did not break out again, the priest was to pronounce the house clean. (Leviticus 14:48.) To purge the house, the priest was to take two birds, cedar wood, crimson stuff, and hyssop, slaughter one bird over fresh water, sprinkle on the house seven times with the bird’s blood, and then let the live bird go free. (Leviticus 14:49–53.)

Male genital discharge

God then told Moses and Aaron the ritual for cleansing a person who had a genital discharge. (Leviticus 15.)

When a man had a discharge from his genitals, he was unclean, and any bedding on which he lay and every object on which he sat was to be unclean. (Leviticus 15:2–4.) Anyone who touched his body, touched his bedding, touched an object on which he sat, was touched by his spit, or was touched by him before he rinsed his hands was to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:5–11.) An earthen vessel that he touched was to be broken, and any wooden implement was to be rinsed with water. (Leviticus 15:12.) Seven days after the discharge ended, he was to wash his clothes, bathe his body in fresh water, and be clean. (Leviticus 15:13.) On the eighth day, he was to give two turtle doves or two pigeons to the priest, who was to offer them to make expiation. (Leviticus 15:14–15.)

When a man had an emission of semen, he was to bathe and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:16.) All material on which semen fell was to be washed in water and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:17.) And if a man had carnal relations with a woman, they were both to bathe and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:18.)

Menstruation

When a woman had a menstrual discharge, she was to remain impure seven days, and whoever touched her was to be unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:19.) Anything that she lay on or sat on was unclean. (Leviticus 15:20.) Anyone who touched her bedding or any object on which she has sat was to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 15:21–23.) And if a man lay with her, her impurity was communicated to him and he was to be unclean seven days, and any bedding on which he lay became unclean. (Leviticus 15:24.) When a woman had an irregular discharge of blood, she was to be unclean as long as her discharge lasted. (Leviticus 15:25–27.) Seven days after the discharge ended, she was to be clean. (Leviticus 15:28.) On the eighth day, she was to give two turtle doves or two pigeons to the priest, who was to offer them to make expiation. (Leviticus 15:29–30.)

God told Moses and Aaron to put the Israelites on guard against uncleanness, lest they die by defiling God’s Tabernacle. (Leviticus 15:31.)

In inner-biblical interpretation

Leviticus chapter 14

Leviticus 13–14 associates skin disease with uncleanness, and Leviticus 15 associates various sexuality-related events with uncleanness. In the Hebrew Bible, uncleanness has a variety of associations. Leviticus 11:8, 11; 21:1–4, 11; and Numbers 6:6–7; and 19:11–16; associate it with death. And perhaps similarly, Leviticus 12 associates it with childbirth and Leviticus 13–14 associates it with skin disease. Leviticus 15 associates it with various sexuality-related events. And Jeremiah 2:7, 23; 3:2; and 7:30; and Hosea 6:10 associate it with contact with the worship of alien gods.

The Hebrew Bible reports skin disease (tzara’at, צָּרַעַת) and a person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע) at several places, often (and sometimes incorrectly) translated as “leprosy” and “a leper.” In Exodus 4:6, to help Moses to convince others that God had sent him, God instructed Moses to put his hand into his bosom, and when he took it out, his hand was “leprous (m’tzora’at, מְצֹרַעַת), as white as snow.” In Leviticus 13–14, the Torah sets out regulations for skin diseases (tzara’at, צָרַעַת) and a person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע). In Numbers 12:10, after Miriam spoke against Moses, God’s cloud removed from the Tent of Meeting and “Miriam was leprous (m’tzora’at, מְצֹרַעַת), as white as snow.” In Deuteronomy 24:8–9, Moses warned the Israelites in the case of skin disease (tzara’at, צָּרַעַת) diligently to observe all that the priests would teach them, remembering what God did to Miriam. In 2 Kings 5:1–19, part of the haftarah for parshah Tazria, the prophet Elisha cures Naaman, the commander of the army of the king of Aram, who was a “leper” (metzora, מְּצֹרָע). In 2 Kings 7:3–20, part of the haftarah for parshah Metzora, the story is told of four “leprous men” (m’tzora’im, מְצֹרָעִים) at the gate during the Arameans’ siege of Samaria. And in 2 Chronicles 26:19, after King Uzziah tried to burn incense in the Temple in Jerusalem, “leprosy (tzara’at, צָּרַעַת) broke forth on his forehead.”

In classical rabbinic interpretation

Leviticus chapter 14

Tractate Negaim in the Mishnah and Tosefta interpreted the laws of skin disease in Leviticus 14. (Mishnah Negaim 1:1–14:13; Tosefta Negaim 1:1–9:9.)

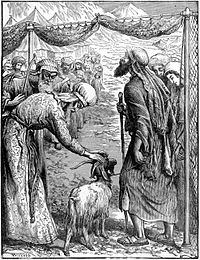

Leviticus 18:4 calls on the Israelites to obey God’s “statutes” (hukim) and “ordinances” (mishpatim). The Rabbis in a Baraita taught that the “ordinances” (mishpatim) were commandments that logic would have dictated that we follow even had Scripture not commanded them, like the laws concerning idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery, and blasphemy. And “statutes” (hukim) were commandments that the Adversary challenges us to violate as beyond reason, like those relating to purification of the person with tzaraat (in Leviticus 14), shaatnez (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), halizah (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), and the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16). So that people do not think these “ordinances” (mishpatim) to be empty acts, in Leviticus 18:4, God says, “I am the Lord,” indicating that the Lord made these statutes, and we have no right to question them. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 67b.)

Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Joseph ben Zimra that anyone who bears evil tales (lashon hara) will be visited by skin disease (tzaraat), as it is said in Psalm 101:5: “Whoever slanders his neighbor in secret, him will I destroy (azmit).” The Gemara read azmit to allude to tzaraat, and cited how Leviticus 25:23 says “in perpetuity” (la-zemitut). And Resh Lakish interpreted the words of Leviticus 14:2, “This shall be the law of the person with skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע),” to mean, “This shall be the law for him who brings up an evil name (motzi shem ra).” (Babylonian Talmud Arachin 15b.)

Similarly, Rabbi Haninah taught that skin disease came only from slander. The Rabbis found a proof for this from the case of Miriam, arguing that because she uttered slander against Moses, plagues attacked her. And the Rabbis read Deuteronomy 24:8–9 to support this when it says in connection with skin disease, “remember what the Lord your God did to Miriam.” (Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8.)

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that skin disease results from seven things: slander, the shedding of blood, vain oath, incest, arrogance, robbery, and envy. The Gemara cited scriptural bases for each of the associations: For slander, Psalm 101:5; for bloodshed, 2 Samuel 3:29; for a vain oath, 2 Kings 5:23–27; for incest, Genesis 12:17; for arrogance, 2 Chronicles 26:16–19; for robbery, Leviticus 14:36 (as a Tanna taught that those who collect money that does not belong to them will see a priest come and scatter their money around the street); and for envy, Leviticus 14:35. (Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 16a.)

Miriam Shut Out from the Camp (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Miriam Shut Out from the Camp (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

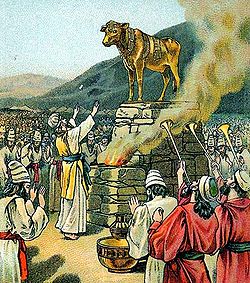

Similarly, a midrash taught that skin disease resulted from 10 sins: (1) idol-worship, (2) unchastity, (3) bloodshed, (4) the profanation of the Divine Name, (5) blasphemy of the Divine Name, (6) robbing the public, (7) usurping a dignity to which one has no right, (8) overweening pride, (9) evil speech, and (10) an evil eye. The midrash cited as proofs: (1) for idol-worship, the experience of the Israelites who said of the Golden Calf, “This is your god, O Israel,” in Exodus 32:4 and then were smitten with leprosy, as reported in Exodus 32:25, where “Moses saw that the people had broken out (parua, פָרֻעַ),” indicating that leprosy had “broken out” (parah) among them; (2) for unchastity, from the experience of the daughters of Zion of whom Isaiah 3:16 says, “the daughters of Zion are haughty, and walk with stretched-forth necks and ogling eyes,” and then Isaiah 3:17 says, “Therefore will the Lord smite with a scab the crown of the head of the daughters of Zion”; (3) for bloodshed, from the experience of Joab, of whom 2 Samuel 3:29 says, “Let it fall upon the head of Joab, and upon all his father's house; and let there not fail from the house of Joab one that hath an issue, or that is a leper,” (4) for the profanation of the Divine Name, from the experience of Gehazi, of whom 2 Kings 5:20 says, “But Gehazi, the servant of Elisha the man of God, said: ‘Behold, my master has spared this Naaman the Aramean, in not receiving at his hands that which he brought; as the Lord lives, I will surely run after him, and take of him somewhat (me'umah, מְאוּמָה),” and “somewhat” (me'umah, מְאוּמָה) means “of the blemish” (mum, מוּם) that Naaman had, and thus Gehazi was smitten with leprosy, as 2 Kings 5:20 reports Elisha said to Gehazi, “The leprosy therefore of Naaman shall cleave to you”; (5) for blaspheming the Divine Name, from the experience of Goliath, of whom 1 Samuel 17:43 says, “And the Philistine cursed David by his God,” and the 1 Samuel 17:46 says, “This day will the Lord deliver (sagar, סַגֶּרְ) you,” and the term “deliver” (sagar, סַגֶּרְ) is used here in the same sense as Leviticus 13:5 uses it with regard to leprosy, when it is says, “And the priest shall shut him up (sagar)”; (6) for robbing the public, from the experience of Shebna, who derived illicit personal benefit from property of the Sanctuary, and of whom Isaiah 22:17 says, “the Lord . . . will wrap you round and round,” and “wrap” must refer to a leper, of whom Leviticus 13:45 says, “And he shall wrap himself over the upper lip”; (7) for usurping a dignity to which one has no right, from the experience of Uzziah, of whom 2 Chronicles 26:21 says, “And Uzziah the king was a leper to the day of his death”; (8) for overweening pride, from the same example of Uzziah, of whom 2 Chronicles 26:16 says, “But when he became strong, his heart was lifted up, so that he did corruptly and he trespassed against the Lord his God”; (9) for evil speech, from the experience of Miriam, of whom Numbers 12:1 says, “And Miriam . . . spoke against Moses,” and then Numbers 12:10 says, “when the cloud was removed from over the Tent, behold Miriam was leprous”; and (10) for an evil eye, from the person described in Leviticus 14:35, which can be read, “And he that keeps his house to himself shall come to the priest, saying: There seems to me to be a plague in the house,” and Leviticus 14:35 thus describes one who is not willing to permit any other to have any benefit from the house. (Leviticus Rabbah 17:3.)

Similarly, Rabbi Judah the Levite, son of Rabbi Shalom, inferred that skin disease comes because of eleven sins: (1) for cursing the Divine Name, (2) for immorality, (3) for bloodshed, (4) for ascribing to another a fault that is not in him, (5) for haughtiness, (6) for encroaching upon other people's domains, (7) for a lying tongue, (8) for theft, (9) for swearing falsely, (10) for profanation of the name of Heaven, and (11) for idolatry. Rabbi Isaac added: for ill-will. And our Rabbis said: for despising the words of the Torah. (Numbers Rabbah 7:5.)

A midrash taught that Divine Justice first attacks a person’s substance and then the person’s body. So when leprous plagues come upon a person, first they come upon the fabric of the person’s house. If the person repents, then Leviticus 14:40 requires that only the affected stones need to be pulled out; if the person does not repent, then Leviticus 14:45 requires pulling down the house. Then the plagues come upon the person’s clothes. If the person repents, then the clothes require washing; if not, they require burning. Then the plagues come upon the person’s body. If the person repents, Leviticus 14:1–32 provides for purification; if not, then Leviticus 13:46 ordains that the person “shall dwell alone.” (Leviticus Rabbah 17:4; Ruth Rabbah 2:10.)

Similarly, the Tosefta reported that when a person would come to the priest, the priest would tell the person to engage in self-examination and turn from evil ways. The priest would continue that plagues come only from gossip, and skin disease from arrogance. But God would judge in mercy. The plague would come to the house, and if the homeowner repented, the house required only dismantling, but if the homeowner did not repent, the house required demolition. They would appear on clothing, and if the owner repented, the clothing required only tearing, but if the owner did not repent, the clothing required burning. They would appear on the person’s body, and if the person repented, well and good, but if the person did not repent, Leviticus 13:46 required that the person “shall dwell alone.” (Tosefta Negaim 6:7.)

Pigeons (painting circa 1832–1837 by John Gould)

Pigeons (painting circa 1832–1837 by John Gould)

In the priest’s examination of skin disease mandated by Leviticus 13:2, 9, and 14:2, the Mishnah taught that a priest could examine anyone else’s symptoms, but not his own. And Rabbi Meir taught that the priest could not examine his relatives. (Mishnah Negaim 2:5; Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8.) The Mishnah taught that the priests delayed examining a bridegroom — as well as his house and his garment — until after his seven days of rejoicing, and delayed examining anyone until after a holy day. (Mishnah Negaim 3:2.)

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that Leviticus 14:4 required “two living clean birds” to be brought to purify the person afflicted with skin disease because the afflicted person did the work of a babbler in spreading evil tales, and therefore Leviticus 14:4 required that the afflicted person offer babbling birds as a sacrifice. (Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 16b.)

The Gemara interpreted the expression “two living birds” in Leviticus 14:4. The Gemara interpreted the word “living” to mean those whose principal limbs are living (excluding birds that are missing a limb) and to exclude treifah birds (birds with an injury or defect that would prevent them from living out a year). The Gemara interpreted the word “birds” (צִפֳּרִים, zipparim) to mean kosher birds. The Gemara deduced from the words of Deuteronomy 14:11, “Every bird (צִפּוֹר, zippor) that is clean you may eat,” that some zipparim are forbidden as unclean — namely, birds slaughtered pursuant to Leviticus 14. The Gemara interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 14:12, “And these are they of which you shall not eat,” to refer to birds slaughtered pursuant to Leviticus 14. And the Gemara taught that Deuteronomy 14:11–12 repeats the commandment so as to teach that one who consumes a bird slaughtered pursuant to Leviticus 14 infringes both a positive and a negative commandment. (Babylonian Talmud Chullin 139b–40a.)

Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel interpreted the words “completely blue (תְּכֵלֶת, tekhelet)” in Exodus 28:31 to teach that blue dye used to test the dye is unfit for further use to dye the blue, tekhelet strand of a tzitzit, interpreting the word “completely” to mean “full strength.” But Rabbi Johanan ben Dahabai taught that even the second dyeing using the same dye is valid, reading the words “and scarlet” (וּשְׁנִי תוֹלַעַת, ushni tolalat) in Leviticus 14:4 to mean “a second [dying] of red wool.” (Babylonian Talmud Menachot 42b.)

A midrash noted that God commanded the Israelites to perform certain precepts with similar material from trees: God commanded that the Israelites throw cedar wood and hyssop into the Red Heifer mixture of Numbers 19:6 and use hyssop to sprinkle the resulting waters of lustration in Numbers 19:18; God commanded that the Israelites use cedar wood and hyssop to purify those stricken with skin disease in Leviticus 14:4–6; and in Egypt God commanded the Israelites to use the bunch of hyssop to strike the lintel and the two side-posts with blood in Exodus 12:22. (Exodus Rabbah 17:1.)

A midrash interpreted the words, “And he spoke of trees, from the cedar that is in Lebanon even to the hyssop that springs out of the wall,” in 1 Kings 5:13 to teach that Solomon interpreted the requirement in Leviticus 14:4–6 to use cedar wood and hyssop to purify those stricken with skin disease. Solomon asked why the person stricken with skin disease was purified by means of the tallest and lowest of trees. And Solomon answered that the person’s raising himself up like a cedar caused him to be smitten with skin disease, but making himself small and humbling himself like the hyssop caused him be healed. (Ecclesiastes Rabbah 7:35.)

When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel, he said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that there were three red threads: one in connection with the red cow in Numbers 19:6, the second in connection with the scapegoat in the Yom Kippur service of Leviticus 16:7–10 (which Mishnah Yoma 4:2 indicates was marked with a red thread), and the third in connection with the person with skin disease (the m’tzora) in Leviticus 14:4. Rav Dimi reported that one weighed ten zuz, another weighed two selas, and the third weighed a shekel, but he could not say which was which. When Rabin came, he said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the thread in connection with the red cow weighed ten zuz, that of the scapegoat weighed two selas, and that of the person with skin disease weighed a shekel. Rabbi Johanan said that Rabbi Simeon ben Halafta and the Sages disagreed about the thread of the red cow, one saying that it weighed ten shekels, the other that it weighed one shekel. Rabbi Jeremiah of Difti said to Rabina that they disagreed not about the thread of the red cow, but about that of the scapegoat. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b–42a.)

Tractate Kinnim in the Mishnah interpreted the laws of pairs of sacrificial pigeons and doves in Leviticus 1:14, 5:7, 12:6–8, 14:22, and 15:29; and Numbers 6:10. (Mishnah Kinnim 1:1–3:6.)

The Levant in the 9th Century B.C.E.

In Leviticus 14:33–34, God announced that God would “put the plague of leprosy in a house of the land of your possession.” Rabbi Hiyya asked: Was it then a piece of good news that plagues were to come upon them? Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai answered that when the Canaanites heard that the Israelites were approaching, they hid their valuables in their houses. But God promised the Israelites’ forbearers that God would bring the Israelites into a land full of good things, including (in the words of Deuteronomy 6:11) “houses full of all good things.” So God brought plagues upon a house of one of the Israelites so that when he would pull it down, he would find a treasure. (Leviticus Rabbah 17:6.)

The Sifra read the words “the land of Canaan” in Leviticus 14:34 to refer to the Land that God set aside distinctly for the Israelites. The Sifra thus read the words “which I give to you” in Leviticus 14:34 to exclude the lands of Ammon and Moab east of the Jordan River. Thus house plagues could occur only in the Land of Israel west of the Jordan. (Sifra Mesora 155:1:1.) And Rabbi Ishmael read the words “of your possession” in Leviticus 14:34 to exclude the possession of Gentiles in the Land of Israel from house plagues. (Sifra Mesora 155:1:6; see also Mishnah Negaim 12:1.)

Because Leviticus 14:34 addresses “a house of the land,” the Mishnah taught that a house built on a ship, on a raft, or on four beams could not be afflicted by a house plague. (Mishnah Negaim 12:1.)

A midrash noted the difference in wording between Genesis 47:27, which says of the Israelites in Goshen that “they got possessions therein,” and Leviticus 14:34, which says of the Israelites in Canaan, “When you come into the land of Canaan, which I gave you for a possession.” The midrash read Genesis 47:27 to read, “and they were taken in possession by it.” The midrash thus taught that in the case of Goshen, the land seized the Israelites, so that their bond might be exacted and so as to bring about God's declaration to Abraham in Genesis 15:13 that the Egyptians would afflict the Israelites for 400 years. But the midrash read Leviticus 14:34 to teach the Israelites that if they were worthy, the Land of Israel would be an eternal possession, but if not, they would be banished from it. (Genesis Rabbah 95.)

The Rabbis taught that a structure of less than four square cubits could not contract a house plague. The Gemara explained that in speaking of house plagues, Leviticus 14:35 uses the word “house,” and a building of less than four square cubits did not constitute a “house.” (Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 3a–b.)

bronze ax heads of the type used between 1500 B.C.E. and 500 B.C.E. in the region of the Adriatic Sea (2008 drawing by Bratislav Tabaš)

bronze ax heads of the type used between 1500 B.C.E. and 500 B.C.E. in the region of the Adriatic Sea (2008 drawing by Bratislav Tabaš)

A Baraita (which the Gemara later said may have reflected the view of Rabbi Meir, or may have reflected the view of the Rabbis) taught that a synagogue, a house owned by partners, and a house owned by a woman are all subject to uncleanness from house plagues. The Gemara explained that the Baraita needed to expound this because one might have argued that Leviticus 14:35 says, “then he who owns the house shall come and tell the priest,” and “he who owns the house” could be read to imply “he” but not “she” and “he” but not “they.” And therefore the Baraita teaches that one should not read Leviticus 14:35 that narrowly. And the Gemara explained that one should not read Leviticus 14:35 that narrowly because Leviticus 14:34 speaks broadly of “a house of the land of your possession,” indicating that all houses in the Land of Israel are susceptible to plagues. The Gemara then asked why Leviticus 14:35 bothers to say, “he who owns the house.” The Gemara explained that Leviticus 14:35 intends to teach that if a homeowner keeps his house to himself exclusively, refusing to lend his belongings, pretending that he did not own them, then God exposes the homeowner by subjecting his house to the plague and causing his belongings to be removed for all to see (as Leviticus 14:36 requires). Thus Leviticus 14:35 excludes from the infliction of house plagues homeowners who lend their belongings to others. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 11b.)

Similarly, Rabbi Isaac taught that when a person asked to borrow a friend’s ax or sieve, and the friend out of selfishness replied that he did not have one, then immediately the plague would attack the friend’s house. And as Leviticus 14:36 required that they remove everything that he had in his house, including his axes and his sieves, the people would see his possessions and exclaim how selfish he had been. (Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8; see also Leviticus Rabbah 17:2.)

But the Gemara asked whether a synagogue could be subject to house plagues. For a Baraita (which the Gemara later identified with the view of the Rabbis) taught that one might assume that synagogues and houses of learning are subject to house plagues, and therefore Leviticus 14:35 says, “he who has the house will come,” to exclude those houses — like synagogues — that do not belong to any one individual. The Gemara proposed a resolution to the conflict by explaining that the first Baraita reflected the opinion of Rabbi Meir, while the second Baraita reflected the opinion of the Rabbis. For a Baraita taught that a synagogue that contains a dwelling for the synagogue attendant is required to have a mezuzah, but a synagogue that contains no dwelling, Rabbi Meir declares it is required to have a mezuzah, but the Sages exempt it. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 11b.)

The Second Temple in Jerusalem (model in the Israel Museum)

The Second Temple in Jerusalem (model in the Israel Museum)

Alternatively, the Gemara suggested that both teachings were in accord with the Rabbis. In the first case, the synagogue referred to has a dwelling, and then even the Rabbis would say that it would be subject to house plagues. In the other case, the synagogue referred to has no dwelling, and so would not be subject to house plagues. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 11b.)

Alternatively, the Gemara tentatively suggested that in both cases, the synagogue has no dwelling, but the first teaching refers to urban synagogues, while the second refers to rural synagogues. But the Gemara asked whether urban synagogues really are not subject to uncleanness from house plagues. For a Baraita taught that the words, “in the house of the land of your possession” in Leviticus 14:34 teach that a house of the land of the Israelites’ possession could become defiled through house plagues, but Jerusalem could not become defiled through house plagues, because Jerusalem did not fall within any single Tribe’s inheritance. Rabbi Judah, however, said that he had heard that only the Temple in Jerusalem was unaffected by house plagues. Thus Rabbi Judah’s view would imply that synagogues and houses of learning are subject to house plagues even in large cities. The Gemara suggested, however, that one should read Rabbi Judah’s view to say that sacred places are not subject to house plagues. The Gemara suggested that the principle that the first Tanna and Rabbi Judah were disputing was whether Jerusalem was divided among the Tribes; the first Tanna holds that Jerusalem was not divided, while Rabbi Judah holds that Jerusalem was divided among the Tribes. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 11b–12a.)

But the Gemara asked whether even rural synagogues could be subject to house plagues. For a Baraita taught that the words, “in the house of the land of your possession” in Leviticus 14:34 teach that house plagues would not affect the Israelites until they conquered the Land of Israel. Furthermore, if the Israelites had conquered the Land but not yet divided it among the Tribes, or even divided it among the Tribes but not divided it among the families, or even divided it among the families but not given each person his holding, then house plagues would not yet affect the Israelites. It is to teach this result that Leviticus 14:35 says, “he who has the house,” teaching that house plagues can occur only to those in the Land of Israel to whom alone the house belongs, excluding these houses that do not belong to an owner alone. Thus the Gemara rejected the explanation based on differences between urban and rural synagogues. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 12a.)

a cruse (drawing by Pearson Scott Foresman)

a cruse (drawing by Pearson Scott Foresman)

The Mishnah interpreted the words, “there seems to me to be as it were a plague in the house,” in Leviticus 14:35 to teach that even a learned sage who knows that he has definitely seen a sign of plague in a house may not speak with certainty. Rather, even the sage must say, “there seems to me to be as it were a plague in the house.” (Mishnah Negaim 12:5; Sifra Mesora 155:1:9.)

The Mishnah interpreted the instruction to empty the house in Leviticus 14:36. Rabbi Judah taught that they removed even bundles of wood and even bundles of reeds. Rabbi Simeon remarked that this (removal of bundles that are not susceptible to uncleanness) was idle business. But Rabbi Meir responded by asking which of the homeowner’s goods could become unclean. Articles of wood, cloth, or metal surely could be immersed in a ritual bath and become clean. The only thing that the Torah spared was the homeowner’s earthenware, even his cruse and his ewer (which, if the house proved unclean, Leviticus 15:12 indicates would have to be broken). If the Torah thus spared a person’s humble possessions, how much more so would the Torah spare a person’s cherished possessions. If the Torah shows so much consideration for material possessions, how much more so would the Torah show for the lives of a person’s children. If the Torah shows so much consideration for the possessions of a wicked person (if we take the plague as a punishment for the sin of slander), how much more so would the Torah show for the possessions of a righteous person. (Mishnah Negaim 12:5; Sifra Mesora 155:1:13.)

Reading Leviticus 14:37 to say, “And he shall look on the plague, and behold the plague,” the Sifra interpreted the double allusion to teach that a sign of house plague was no cause of uncleanness unless it appeared in at least the size of two split beans. (Sifra Mesora 156:1:1.) And because Leviticus 14:37 addresses the house’s “walls” in the plural, the Sifra taught that a sign of house plague was no cause of uncleanness unless it appeared on at least four walls. (Sifra Mesora 156:1:2.) Consequently, the Mishnah taught that a round house or a triangular house could not contract uncleanness from a house plague. (Mishnah Negaim 12:1; Sifra Mesora 156:1:2.)

Because Leviticus 14:40 addresses the house’s “stones” in the plural, Rabbi Akiba ruled that a sign of house plague was no cause of uncleanness unless it appeared in at least the size of two split beans on two stones, and not on only one stone. And because Leviticus 14:37 addresses the house’s “walls” in the plural, Rabbi Eliezer son of Rabbi Simeon said that a sign of house plague was no cause of uncleanness unless it appeared in the size of two split beans, on two stones, on two walls in a corner, its length being that of two split beans and its breadth that of one split bean. (Mishnah Negaim 12:3.)

Because Leviticus 14:45 addresses the “stones,” “timber,” and “mortar” of the house afflicted by a house plague, the Mishnah taught that only a house made of stones, timber, and mortar could be afflicted by a house plague. (Mishnah Negaim 12:2.) And the Mishnah taught that the quantity of wood must be enough to build a threshold, and quantity of mortar must be enough to fill up the space between one row of stones and another. (Mishnah Negaim 12:4.)

A Baraita taught that there never was a leprous house within the meaning of Leviticus 14:33–53 and never will be. The Gemara asked why then the law was written, and replied that it was so that one may study it and receive reward. But Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Zadok and Rabbi Simeon of Kefar Acco both cited cases where local tradition reported the ruins of such houses, in Gaza and Galilee, respectively. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 71a.)

The Chaldees Destroy the Brazen Sea (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

The Chaldees Destroy the Brazen Sea (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

A midrash read the discussion of the house stricken with plague in Leviticus 14:33–53 as a prophecy. The midrash read the words, “and I put the plague of leprosy in a house of the land of your possession,” in Leviticus 14:34 to allude to the Temple, about which in Ezekiel 24:21 God says, “I will defile My sanctuary, the pride of your power, the desire of your eyes, and the longing of your soul.” The midrash read the words, “then He whose house it is shall come,” in Leviticus 14:35 to allude to God, about Whom Haggai 1:4 says, “Because of My house that lies waste.” The midrash read the words, “and He shall tell the priest,” in Leviticus 14:35 to allude to Jeremiah, who Jeremiah 1:1 identified as a priest. The midrash read the words, “there seems to me to be, as it were, a plague in the house,” in Leviticus 14:35 to allude to the idol that King Manasseh set up in 2 Kings 21:7. The midrash read the words, “and the priest shall command that they empty the house,” in Leviticus 14:36 to allude to King Shishak of Egypt, who 1 Kings 14:26 reports, “took away the treasures of the house of the Lord.” The midrash read the words, “and he shall break down the house,” in Leviticus 14:45 to allude to King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, who Ezra 5:12 reports destroyed the Temple. The midrash read the words, “and they shall pour out the dust that they have scraped off outside the city,” in Leviticus 14:41 to allude to the Israelites taken away to the Babylonian Captivity, whom Ezra 5:12 reports Nebuchadnezzar “carried . . . away into Babylon.” And the midrash read the words, “and they shall take other stones, and put them in the place of those stones,” in Leviticus 14:42 to allude to the Israelites who would come to restore Israel, and of whom Isaiah 28:16 reports God saying, “Behold, I lay in Zion for a foundation stone, a tried stone, a costly corner-stone of sure foundation; he that believes shall not make haste.” (Leviticus Rabbah 17:7.)

Leviticus chapter 15

Tractate Zavim in the Mishnah and Tosefta interpreted the laws of male genital discharges in Leviticus 15:1–18. (Mishnah Zavim 1:1–5:12; Tosefta Zavim 1:1–5:12.)

The Mishnah taught that they inquired along seven lines before they determined that a genital discharge rendered a man unclean. A discharge caused by one of these reasons did not render the man impure or subject him to bringing an offering. They asked: (1) about his food, (2) about his drink, (3) what he had carried, (4) whether he had jumped, (5) whether he had been ill, (6) what he had seen, and (7) whether he had obscene thoughts. It did not matter whether he had had thoughts before or after seeing a woman. Rabbi Judah taught that the discharge would not render him unclean if he had watched animals having intercourse or even if he merely saw a woman's dyed garments. Rabbi Akiba taught that the discharge would not render him unclean even if he had eaten any kind of food, good or bad, or had drunk any kind of liquid. The Sages exclaimed to Rabbi Akiba that according to his view, no more men would ever be rendered unclean by genital discharge. Rabbi Akiba replied that one does not have an obligation to ensure that there exist men unclean because of a genital discharges. (Mishnah Zavim 2:2.)

Rabbi Eleazar ben Hisma taught that even the apparently arcane laws of bird offerings in Leviticus 12:8 and menstrual cycles in Leviticus 12:1–8 and 15:19–33 are essential laws. (Mishnah Avot 3:18.)

Tractate Niddah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of menstruation in Leviticus 15:19–33. (Mishnah Niddah 1:1–10:8; Tosefta Niddah 1:1–9:19; Jerusalem Talmud Niddah 1a–; Babylonian Talmud Niddah 2a–73a.)

Rabbi Meir taught that the Torah ordained that menstruation should separate a wife from her husband for seven days, because if the husband were in constant contact with his wife, the husband might become disenchanted with her. The Torah, therefore, ordained that a wife might be unclean for seven days (and therefore forbidden to her husband for intercourse) so that she should become as desirable to her husband as when she first entered the bridal chamber. (Babylonian Talmud Niddah 31b.)

Interpreting the beginning of menstrual cycles, as in Leviticus 15:19–33, the Mishnah ruled that if a woman loses track of her menstrual cycle, there is no return to the beginning of the niddah count in fewer than seven, nor more than seventeen days. (Mishnah Arakhin 2:1; Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 8a.)

The Mishnah taught that a woman may attribute a bloodstain to any external cause to which she can possibly attribute it and thus regard herself as clean. If, for instance, she had killed an animal, she was handling bloodstains, she had sat beside those who handled bloodstains, or she had killed a louse, she may attribute the stain to those external causes. (Mishnah Niddah 8:2; Babylonian Talmud Niddah 58b.)

The Mishnah related that a woman once came to Rabbi Akiba and told him that she had observed a bloodstain. He asked her whether she perhaps had a wound. She replied that she had a wound, but it had healed. He asked whether it was possible that it could open again and bleed. She answered in the affirmative, and Rabbi Akiba declared her clean. Observing that his disciples looked at each other in astonishment, he told them that the Sages did not lay down the rule for bloodstains to create a strict result but rather to produce a lenient result. for it is said in scripture, and if a woman have an issue, and her issue in her flesh be blood.14 only blood15 but not a bloodstain. (Mishnah Niddah 8:3; Babylonian Talmud Niddah 58b.)

Commandments

According Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 11 positive and no negative commandments in the parshah:

- To carry out the prescribed rules for purifying the person affected by tzara'at (Leviticus 14:2.)

- The person affected by tzara'at must shave off all his hair prior to purification. (Leviticus 14:9.)

- Every impure person must immerse in a mikvah to become pure. (Leviticus 14:9.)

- A person affected by tzara'at must bring an offering after going to the mikvah. (Leviticus 14:10.)

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by a house's tzara'at (Leviticus 14:35.)

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by a man's running issue (Leviticus 15:3.)

- A man who had a running issue must bring an offering after he goes to the mikvah. (Leviticus 15:13–14.)

- To observe the laws of impurity of a seminal emission (Leviticus 15:16.)

- To observe the laws of menstrual impurity (Leviticus 15:19.)

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by a woman's running issue (Leviticus 15:25.)

- A woman who had a running issue must bring an offering after she goes to the mikvah. (Leviticus 15:28–29.)

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 2:233–75. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1984. ISBN 0-87306-296-5.)

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parshah is 2 Kings 7:3–20.

Summary

During the Arameans’ siege of Samaria, four leprous men at the gate asked each other why they should die there of starvation, when they might go to the Arameans, who would wither save them or leave them no worse than they were. (2 Kings 7:3–4.) When at twilight, they went to the Arameans’ camp, there was no one there, for God had made the Arameans hear chariots, horses, and a great army, and fearing the Hittites and the Egyptians, they fled, leaving their tents, their horses, their donkeys, and their camp. (2 Kings 7:5–7.) The lepers went into a tent, ate and drank, and carried away silver, gold, and clothing from the tents and hid it. (2 Kings 7:8.)

The four lepers bring the news to the guards at the gate of Samaria (illumination from Petrus Comestor's 1372 Bible Historiale)

The four lepers bring the news to the guards at the gate of Samaria (illumination from Petrus Comestor's 1372 Bible Historiale)

Feeling qualms of guilt, they went to go tell the king of Samaria, and called to the porters of the city telling them what they had seen, and the porters told the king's household within. (2 Kings 7:9–11.) The king arose in the night, and told his servants that he suspected that the Arameans had hidden in the field, thinking that when the Samaritans came out, they would be able to get into the city. (2 Kings 7:12.) One of his servants suggested that some men take five of the horses that remained and go see, and they took two chariots with horses to go and see. (2 Kings 7:13–14.) They went after the Arameans as far as the Jordan River, and all the way was littered with garments and vessels that the Arameans had cast away in their haste, and the messengers returned and told the king. (2 Kings 7:15.) So the people went out and looted Arameans’ camp, so that the price of fine flour and two measures of barley each dropped to a shekel, as God had said it would. (2 Kings 7:16.) And the king appointed the captain on whom he leaned to take charge of the gate, and the people trampled him and killed him before he could taste of the flour, just as the man of God Elisha had said. (2 Kings 7:17–20.)

Connection to the parshah

Both the parshah and the haftarah deal with people stricken with skin disease. Both the parshah and the haftarah employ the term for the person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע). (Leviticus 14:2; 2 Kings 7:3, 8.) Just before parshah Metzora, in the sister parshah Tazria, Leviticus 13:46 provides that the person with skin disease “shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his dwelling be,” thus explaining why the four leprous men in the haftarah lived outside the gate. (2 Kings 7:3.)

Rabbi Johanan taught that the four leprous men at the gate in 2 Kings 7:3 were none other than Elisha’s former servant Gehazi (whom the midrash, above, cited as having been stricken with leprosy for profanation of the Divine Name) and his three sons. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 107b.)

In the parshah, when there “seems” to be a plague in the house (Leviticus 14:35), the priest must not jump to conclusions, but must examine the facts. (Leviticus 14:36–37, 39, 44.) Just before the opening of the haftarah, in 2 Kings 7:2, the captain on whom the king leaned jumps to the conclusion that Elisha’s prophesy could not come true, and the captain meets his punishment in 2 Kings 7:17 and 19. (See Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, 203. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-86705-054-3.)

On Shabbat HaChodesh

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat HaChodesh ("Sabbath [of] the month," the special Sabbath preceding the Hebrew month of Nissan — as it did in 2008), the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 45:16–46:18

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 45:18–46:15

Isaiah (fresco circa 1508–1512 by Michelangelo from the Sistine Chapel)

Isaiah (fresco circa 1508–1512 by Michelangelo from the Sistine Chapel)

Connection to the special Sabbath

On Shabbat HaChodesh, Jews read Exodus 12:1–20, in which God commands that “This month [Nissan] shall be the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year” (Exodus 12:2), and in which God issued the commandments of Passover. (Exodus 12:3–20.) Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 45:21–25 discusses Passover. In both the special reading and the haftarah, God instructs the Israelites to apply blood to doorposts. (Exodus 12:7; Ezekiel 45:19.)

On Shabbat Rosh Chodesh

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (as it did in 2009), the haftarah is Isaiah 66:1–24.

In the liturgy

Some Jews refer to the guilt offerings for skin disease in Leviticus 14:10–12 as part of readings on the offerings after the Sabbath morning blessings. (Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation, 239. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-697-3.)

The laws of a house afflicted with plague in Leviticus 14:34–53 provide an application of the twelfth of the Thirteen Rules for interpreting the Torah in the Baraita of Rabbi Ishmael that many Jews read as part of the readings before the Pesukei d’Zimrah prayer service. The twelfth rule provides that one may elucidate a matter from its context or from a passage following it. Leviticus 14:34–53 describes the laws of the house afflicted with plague generally. But because Leviticus 14:45 instructs what to do with the “stones . . . timber . . . and all the mortar of the house,” the Rabbis interpret the laws of the house afflicted with plague to apply only to houses made of stones, timber, and mortar. (Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 246.)

Further reading

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Exodus 12:22 (hyssop).

- Leviticus 8:23 (right ear, thumb of right hand, and great toe of right foot); 16:10, 20–22 (riddance ritual).

- Numbers 19:6 (cedar wood, hyssop, and red stuff); 19:18 (hyssop).

- Deuteronomy 17:8–9 (priests’ duty to assess); 24:8–9 (priests’ duties regarding skin diseases).

- 2 Kings 5:10–14 (purification from skin disease with living water); 7:3–20 (people with skin disease).

- Zechariah 5:8–9 (transporting away wickedness by wing).

- Psalm 51:9 (“Purge me with hyssop”); 78:5–6 (to teach); 91:10 (plague on dwelling); 119:97–99 (learning from the law).

Early nonrabbinic

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 3:4:15; That the Worse Is Wont To Attack the Better 6:16; On the Unchangableness of God 28:131–35. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 51, 113, 169. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:11:3–4. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 96–97. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Hebrews 9:19 Late 1st century. (scarlet wool and hyssop).

- John 19:29 (hyssop).

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Pesachim 8:5; Shekalim 5:3; Moed Katan 3:1–2; Nazir 7:3; Horayot 1:3; Zevachim 4:3; Menachot 5:6–7, 9:3; Bekhorot 7:2; Arakhin 2:1; Negaim 1:1–14:13; Parah 1:4, 6:5; Niddah 1:1–10:8; Zavim 1:1–5:12. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 245, 259, 327, 443–44, 690, 706, 743, 751, 801, 811, 981–1012, 1014, 1021, 1077–95, 1108–17. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Demai 2:7; Challah 2:7; Sotah 1:8; Menachot 7:16, 10:1; Chullin 10:14; Negaim 1:1–9:9; Niddah 1:1–9:19; Zavim 1:1–5:12. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:85, 339, 835; 2:1404, 1438, 1450, 1709–44, 1779–808, 1887–99. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifra 148:1–173:9. Land of Israel, 4th century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 2:325–429. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-206-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Orlah 6a, 39a; Yoma 16b, 41b; Niddah 1a–. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 12, 21. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007–2011.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 13:1; 57:3; 59:3. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, 43, 258, 268. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006. ISBN 0-8276-0799-7.

- Leviticus Rabbah 16:1–19:6; 34:6. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, 4:199–249, 431. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 2b, 11b, 59a, 62b, 64a–b, 71b, 83a, 84a–b, 86b, 109a, 132a; Eruvin 4a–b, 14b, 51a, 82b; Pesachim 3a, 24a, 59a–b, 65b, 67b–68a, 85b, 90b, 92a, 109a; Yoma 5a, 6a, 11b–12a, 24a, 30b–31a, 41b, 61a–b, 62b, 63a; Sukkah 3a–b, 5b–6a; Beitzah 32a; Taanit 26b; Megillah 8a–b, 20a–21a, 26a; Moed Katan 5a, 7a–b, 13b, 14b, 15a–16a, 17b, 25b, 27b; Chagigah 9b, 11a, 23b; Yevamot 5a, 7a, 17b, 34b, 46b, 49b, 54a, 69b, 73a, 102b, 103b–04a, 105a; Ketubot 61b, 64b, 72a, 75a; Nedarim 35b–36a, 56a–b; Nazir 3b, 5a, 8b, 15b, 25b, 27a, 29a, 38a, 39b, 40b–41a, 43a, 44a–b, 46b, 47b, 54a–b, 56a–b, 57b–58a, 60a–b, 65b–66a; Sotah 5b, 8a, 15b–16b, 29b; Gittin 46a, 82a; Kiddushin 15a, 25a, 33b, 56b–57b, 68a, 70b; Bava Kamma 17b, 24a, 25a–b, 66b, 82a–b; Bava Metzia 31a; Bava Batra 9b, 24a, 164b, 166a; Sanhedrin 45b, 48b, 71a, 87b–88a, 92a; Makkot 13b, 21a; Shevuot 6a–b, 8a, 11a, 14b, 17b, 18a–b; Avodah Zarah 34a, 47b, 74a; Horayot 3b–4a, 8b, 10a; Zevachim 6b, 8a, 17b, 24b, 32b, 40a, 43a, 44a–b, 47b, 49a, 54b, 76b, 90b, 91b, 105a, 112b; Menachot 3a, 5a, 8a, 9a–10a, 15b, 18b, 24a, 27a–b, 35b, 42b, 48b, 61a, 64b, 73a, 76b, 86b, 88a, 89a, 91a, 101b, 106b; Chullin 10b, 24b, 27a, 35a, 49b, 51b, 62a, 71b, 72b, 82a, 85a, 106a, 123b, 128b, 133a, 140a, 141a, 142a; Bekhorot 32a, 38a, 45b; Arakhin 3a, 8a, 15b–17b; Keritot 8a–b, 9b, 10b, 25a, 28a; Meilah 11a, 18a, 19a–b; Niddah 2a–73a. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006.

Medieval

- Exodus Rabbah 17:1. 10th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by S. M. Lehrman, 3:211. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Rashi. Commentary. Leviticus 14–15. Troyes, France, late 11th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 3:159–90. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-028-5.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 3:53. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 181. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, 3:47. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, 367–68, 370. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Zohar 3:52b–56a. Spain, late 13th century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:40. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 503–04. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0-14-043195-0.

- Emily Dickinson. Poem 1733 (No man saw awe, nor to his house). 19th century. In The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, 703. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-18414-4.

- Helen Frenkley. “The Search for Roots—Israel’s Biblical Landscape Reserve.” In Biblical Archaeology Review. 12:5 (Sept./Oct. 1986).

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 1–16, 3:827–1009. New York: Anchor Bible, 1998. ISBN 0-385-11434-6.

- Suzanne A. Brody. “Blood.” In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, 89. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. ISBN 1-60047-112-9.

- Varda Polak-Sahm. The House of Secrets: The Hidden World of the Mikveh. Beacon Press, 2009. ISBN 0807077429.

- “Holy Water: A New Book Reveals the Secrets of the Mikveh.” In Tablet Magazine. (Aug. 31, 2009).

External links

Texts

Commentaries

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University

- Anshe Emes Synagogue, Los Angeles

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- eparsha.com

- G-dcast

- The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash

- Jewish Agency for Israel

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- MyJewishLearning.com

- Ohr Sameach

- Orthodox Union

- OzTorah — Torah from Australia

- Oz Ve Shalom — Netivot Shalom

- Pardes from Jerusalem

- RabbiShimon.com

- Rabbi Shlomo Riskin

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Shiur.com

- 613.org Jewish Torah Audio

- Tanach Study Center

- Teach613.org, Torah Education at Cherry Hill

- Torah from Dixie

- Torah.org

- Torahvort.com

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- What’s Bothering Rashi?

Weekly Torah Portions Genesis Bereishit · Noach · Lech-Lecha · Vayeira · Chayei Sarah · Toledot · Vayetze · Vayishlach · Vayeshev · Miketz · Vayigash · Vayechi

Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Devarim · Va'etchanan · Eikev · Re'eh · Shoftim · Ki Teitzei · Ki Tavo · Nitzavim · Vayelech · Haazinu · V'Zot HaBerachahCategories:- Weekly Torah readings

- Book of Leviticus

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.