- United States presidential election, 1948

-

United States presidential election, 1948

1944 ← November 2, 1948 → 1952

Nominee Harry S. Truman Thomas E. Dewey Strom Thurmond Party Democratic Republican States' Rights Democratic Party (Dixiecrat) Home state Missouri New York South Carolina Running mate Alben W. Barkley Earl Warren Fielding L. Wright Electoral vote 303 189 39 States carried 28 16 4 Popular vote 24,179,347 21,991,292 1,175,930 Percentage 49.6% 45.1% 2.4%

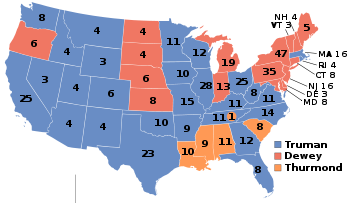

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Truman/Barkley , Red denotes those won by Dewey/Warren, Orange denotes those won by Thurmond/Wright, including a faithless elector in Tennessee. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state.

President before election

Elected President

The United States presidential election of 1948 is considered by most historians as the greatest election upset in American history. Virtually every prediction (with or without public opinion polls) indicated that incumbent President Harry S. Truman would be defeated by Republican Thomas E. Dewey. Truman won, overcoming a three-way split in his own party. Truman's surprise victory was the fifth consecutive win for the Democratic Party in a presidential election. As a result of the 1948 congressional election, the Democrats would regain control of both houses of Congress.[1] Thus, Truman's election confirmed the Democratic Party's status as the nation's majority party, a status it would retain until the conservative realignment in 1968.[2][3]

Contents

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Main article: 1948 Republican National Convention-

Former Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota

-

President pro tempore of the Senate Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan

Both major parties courted General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the most popular general of World War II. Eisenhower's political views were unknown in 1948. He was, later events would prove, a moderate Republican, but in 1948 he flatly refused the nomination of any political party.

With Eisenhower refusing to run, the contest for the Republican nomination was between New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, former Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen, Ohio Senator Robert Taft, California Governor Earl Warren, General Douglas MacArthur and Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan, the senior Republican in the Senate. Governor Dewey, who had been the Republican nominee in 1944, was regarded as the frontrunner when the primaries began. Dewey was the acknowledged leader of the GOP's powerful eastern establishment; in 1946 he had been re-elected Governor of New York by the largest margin in state history. Dewey's handicap was that many Republicans disliked him; he often struck observers as cold, stiff and calculating. Senator Taft was the leader of the GOP's conservative wing. He opened his campaign in 1947 by attacking the Democratic Party's domestic policy and foreign policy. In foreign policy, Taft was an isolationist who blamed Truman for implementing the Morgenthau Plan in occupied Germany, thereby wrecking the European economy which (in his view) thus required rescue from U.S. taxpayers in the form of the Marshall Plan.[4] In domestic issues, Taft and his fellow conservatives wanted to abolish many of the New Deal social welfare programs that had been created in the 1930s; they regarded these programs as too expensive and harmful to business interests. Taft had two major weaknesses: he was seen as a plodding, dull campaigner, and he was viewed by most party leaders as being too conservative and controversial to win a presidential election. Taft's support was limited to his native Midwest and parts of the South. Although both Senator Vandenberg and Governor Warren were highly popular in their home states, both men refused to campaign in the primaries, which limited their chances of winning the nomination. However, their supporters hoped that in the event of a Dewey-Taft-Stassen deadlock, the convention would turn to their man as a compromise candidate. General MacArthur was serving in Japan as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers occupying that nation; as such he was unable to campaign for the nomination. However, he did make it known that he would not decline the GOP nomination if it were offered to him, and some conservative Republicans hoped that by winning a primary contest he could prove his popularity with voters. They chose to enter his name in the Wisconsin primary.

The "surprise" candidate of 1948 was Stassen, the former "boy wonder" of Minnesota politics. Stassen had been elected governor of Minnesota at the age of 31; he resigned as governor in 1943 to serve in the United States Navy in World War II. In 1945 he had served on the committee which created the United Nations. Stassen was widely regarded as the most liberal of the Republican candidates, yet during the primaries he was criticized for being vague on many issues. Stassen stunned Dewey and MacArthur in the Wisconsin primary; Stassen's surprise victory virtually eliminated General MacArthur, whose supporters had made a major effort on his behalf. Stassen defeated Dewey again in the Nebraska primary, thus making him the new frontrunner. He then made the strategic mistake of trying to beat Senator Taft in Taft's home state of Ohio. Stassen believed that if he could defeat Taft in his home state, Taft would be forced to quit the race and most of Taft's delegates would support him instead of Dewey. However, Taft defeated Stassen in his native Ohio, and Stassen earned the hostility of the party's conservatives. Even so, Stassen was still leading Dewey in the polls for the upcoming Oregon primary. However, Dewey, who realized that a defeat in Oregon would end his chances at the nomination, sent his powerful political organization into the state and spent large sums of money on campaign ads in Oregon. Dewey also agreed to debate Stassen in Oregon on national radio - it was the first-ever radio debate between presidential candidates. The sole issue of the debate concerned whether to outlaw the Communist Party of the United States. Stassen, despite his liberal reputation, argued in favor of outlawing the party, while Dewey forcefully argued against it; at one point he famously stated that "you can't shoot an idea with a gun". Most observers rated Dewey as the winner of the debate, and a few days later Dewey defeated Stassen in Oregon. From this point forward, the New York governor had the momentum he needed to win his party's second nomination.

Primaries total popular vote results[5]:

- Earl Warren - 771,295 (26.99%)

- Harold Stassen - 627,321 (21.96%)

- Robert Taft - 464,741 (16.27%)

- Thomas E. Dewey - 330,799 (11.58%)

- Riley A. Bender - 324,029 (11.34%)

- Douglas MacArthur - 87,839 (3.07%)

- Leverett Saltonstall - 72,191 (2.53%)

- Herbert E. Hitchcock - 45,463 (1.59%)

- Edward Martin - 45,072 (1.58%)

- Unpledged delegates - 28,854 (1.01%)

- Arthur H. Vandenberg - 18,924 (0.66%)

- Dwight D. Eisenhower - 5,014 (0.18%)

- Harry S. Truman - 4,907 (0.17%)

- Henry A. Wallace - 1,452 (0.05%)

- Joseph William Martin, Jr. - 974 (0.03%)

Republican Convention

The 1948 Republican National Convention was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first presidential convention to be shown on national television. As the convention opened Dewey was believed to have a large lead in the delegate count. His major opponents – Taft, Stassen, and Senator Vandenberg – met in Taft's hotel suite to plan a "stop-Dewey" movement. However, a key obstacle soon developed when the three men refused to unite behind a single candidate to oppose Dewey. Instead, all three men simply agreed to try to hold their own delegates in the hopes of preventing Dewey from obtaining a majority. This proved to be futile, as Dewey's efficient campaign team methodically gathered the remaining delegates they needed to win the nomination. After the second round of balloting, Dewey was only 33 votes short of victory. Taft then called Stassen and urged him to withdraw from the race and endorse him as Dewey's main opponent. When Stassen refused, Taft wrote a concession speech and had it read at the start of the third ballot; Dewey was then nominated by acclamation. Dewey then chose popular Governor Earl Warren (and future Chief Justice) of California as his running mate. Following the convention, most political experts in the news media rated the GOP ticket as an almost-certain winner over the Democrats.

The tally Ballot 1 2 3 Thomas E. Dewey 434 515 1094 Robert Taft 224 274 0 Harold Stassen 157 149 0 Arthur H. Vandenberg 62 62 0 Earl Warren 59 57 0 Dwight H. Green 56 0 0 Alfred E. Driscoll 35 0 0 Raymond E. Baldwin 19 19 0 Joseph William Martin, Jr. 18 10 0 B. Carroll Reece 15 0 0 Douglas MacArthur 11 8 0 Everett Dirksen 1 0 0 Abstaining 1 0 0 Democratic Party nomination

Main article: 1948 Democratic National ConventionDemocratic candidates:

On July 12, the Democratic National Convention convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the same arena where the Republicans had met a few weeks earlier. Spirits were low: the Republicans had taken control of both houses of the United States Congress and a majority of state governorships during the 1946 midterm elections by running against Truman, and the public-opinion polls showed Truman trailing Republican nominee Dewey, sometimes by double digits. Furthermore, some liberal Democrats had joined Henry A. Wallace's new Progressive Party, and party leaders feared that Wallace would take enough votes from Truman to give the large Northern and Midwestern states to the Republicans.

As a result of Truman's low standing in the polls, several Democratic party bosses began working to "dump" Truman and nominate a more popular candidate. Among the leaders of this movement were Jacob Arvey, the boss of the Chicago Democratic organization, Frank Hague, the boss of New Jersey, James Roosevelt, the eldest son of former President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Senator Claude Pepper of Florida. The primary target of the rebels was General Dwight D. Eisenhower; in 1947, Truman had offered to run as Eisenhower's running mate on the Democratic ticket if General Douglas MacArthur won the Republican nomination.[6] Despite their efforts, however, Eisenhower refused to become a candidate (in 1952, he revealed that he was a Republican). Rebuffed, the leaders of the "dump" Truman movement then reluctantly agreed to support Truman for the nomination. At the Democratic Convention, a group of Northern liberals, led by Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey, successfully pushed through a platform (over vigorous Southern opposition) that promoted civil rights for blacks. In his speech promoting the civil rights platform, Humphrey memorably stated that "the time has come for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights!" Ironically, while Truman and his staff were ambivalent about supporting the civil rights plank, it did receive strong support from many of the big-city party bosses, most of whom felt that the civil rights platform would encourage the growing black population in their cities to vote for the Democrats. The passage of the civil rights platform caused some three dozen Southern delegates, led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, to walk out of the convention; the Southern delegates who remained nominated Senator Richard Russell, Jr. of Georgia for the Democratic nomination as a rebuke to Truman. Nonetheless, 947 Democratic delegates voted for Truman as the Democratic nominee, while Russell received only 266 votes, all from the South. Truman then selected Kentucky Senator Alben W. Barkley, who had delivered the convention's keynote address, as his running mate, with this nomination being made by acclamation.

The Balloting Presidential Ballot Vice Presidential Ballot Harry S. Truman 947.5 Alben W. Barkley 1,234 Richard Russell, Jr. 266 James A. Roe 15 Paul V. McNutt 2 Alben W. Barkley 1 Progressive Party nomination

Progressive Party nominee Henry A. Wallace, former Vice President of the United States under Franklin D. Roosevelt

Progressive Party nominee Henry A. Wallace, former Vice President of the United States under Franklin D. Roosevelt

Meanwhile, the Democratic party had fragmented. A new Progressive Party — the name had been used earlier by Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 and Robert M. La Follette in 1924 — was created afresh in 1948 with the nomination of Henry A. Wallace, who had served as Secretary of Agriculture, Vice President of the United States, and Secretary of Commerce under Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1946 President Truman had fired Wallace as Secretary of Commerce when Wallace publicly opposed Truman's firm moves to counter the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Wallace's 1948 platform opposed the Cold War policies of President Truman, including the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine. The Progressives proposed stronger government regulation and control of Big Business. They also campaigned to end discrimination against blacks and women, backed a minimum wage and called for the elimination of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was investigating the issue of communist spies within the U.S. government and labor unions. Wallace and his supporters believed that the committee was violating the civil liberties of government workers and labor unions. However, the Progressives also generated a great deal of controversy, due to the widespread belief that they were secretly controlled by Communists who were more loyal to the Soviet Union than the United States. Wallace himself denied being a Communist, but he repeatedly refused to disavow their support, and at one point was quoted as saying that the "Communists are the closest thing to the early Christian martyrs." Wallace was also hurt when Westbrook Pegler, a prominent conservative newspaper columnist, revealed that Wallace as Vice President had written coded letters discussing prominent politicians such as Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill to his Russian New Age spiritual guru, Nicholas Roerich. This revelation - and quotes from the letters were published - led to much ridicule of Wallace in the national press.

The Progressive Party Convention, which was held in Philadelphia, was a highly contentious affair; several famous newspaper journalists, such as H. L. Mencken and Dorothy Thompson, publicly accused the Progressives of being covertly controlled by Communists. Several leading figures of the Progressive Party (such as socialist leader Norman Thomas) quit the party in protest over what they perceived as the undue influence Communists exerted over Wallace. Thomas ran as the Socialist Party presidential candidate to offer an alternative to Wallace.

Senator Glen H. Taylor of Idaho, an eccentric figure who was known as a "singing cowboy" and who had ridden his horse "Nugget" up the steps of the United States Capitol after winning election to the Senate in 1944, was named as Wallace's running mate.

States' Rights Democratic Party nomination

The Southern Democrats who had bolted the Democratic Convention over Truman's civil rights platform promptly met at Municipal Auditorium in Birmingham, Alabama and formed yet another political party, which they named the "States' Rights" Democratic Party. More commonly known as the “Dixiecrats”, the party's main goal was continuing the policy of racial segregation in the South and the Jim Crow laws that sustained it. South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, who had led the walkout, became the party's presidential nominee. Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright received the vice presidential nomination. The Dixiecrats had no chance of winning the election themselves, since they were not on the ballot in enough states. Their strategy was to take enough Southern states from Truman to force the election into the United States House of Representatives, where they could then extract concessions from either Truman or Dewey on racial issues in exchange for their support. Even if Dewey won the election outright, the Dixiecrats hoped that their defection would show that the Democratic Party needed Southern support in order to win national elections, and that this fact would weaken the pro-civil rights movement among Northern and Western Democrats. However, the Dixiecrats were weakened when most Southern Democratic leaders (such as Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia and "Boss" E. H. Crump of Tennessee) refused to support the party. Despite being an incumbent President, Truman was not placed on the ballot in Alabama.[7] In the states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina, the party was able to be labeled as the main Democratic Party ticket on the local ballots on election night[8] Outside of these four states, however, it was only listed as a third-party ticket.[8]

General election

The fall campaign

Given Truman's sinking popularity and the seemingly fatal three-way split in the Democratic Party, Dewey appeared unbeatable. Top Republicans believed that all their candidate had to do to win was to avoid major mistakes; in keeping with this advice, Dewey carefully avoided risks. He spoke in platitudes, avoided controversial issues, and was vague on what he planned to do as President. Speech after speech was filled with non-political, optimistic assertions of the obvious, including the now infamous quote “You know that your future is still ahead of you.” An editorial in The (Louisville) Courier-Journal summed it up as such: “No presidential candidate in the future will be so inept that four of his major speeches can be boiled down to these historic four sentences: Agriculture is important. Our rivers are full of fish. You cannot have freedom without liberty. Our future lies ahead.”[9] Truman, trailing in the polls, decided to adopt a slashing, no-holds-barred campaign. He ridiculed Dewey by name, criticized Dewey's refusal to address specific issues, and scornfully targeted the Republican-controlled 80th Congress with a wave of relentless, and blistering, partisan assaults. He nicknamed the Republican-controlled Congress as the "do-nothing" Congress, a remark which brought strong criticism from GOP Congressional leaders (such as Senator Taft), but no comment from Dewey. In fact, Dewey rarely mentioned Truman's name during the campaign, which fit into his strategy of appearing to be above petty partisan politics.

President Harry S. Truman at the mike, left Harley O. Staggers & Alben W. Barkley. 1948 in Keyser, West Virginia on Whistle Stop Train

President Harry S. Truman at the mike, left Harley O. Staggers & Alben W. Barkley. 1948 in Keyser, West Virginia on Whistle Stop Train

Under Dewey's leadership, the Republicans had enacted a platform at their 1948 convention that called for expanding social security, more funding for public housing, civil rights legislation, and promotion of health and education by the federal government. These positions were, however, unacceptable to the conservative Congressional Republican leadership. Truman exploited this rift in the opposing party by calling a special session of Congress on “Turnip Day” (referring to an old piece of Missouri folklore about planting turnips in late July) and daring the Republican Congressional leadership to pass its own platform. The 80th Congress played into Truman's hands, delivering very little in the way of substantive legislation during this time. The GOP's lack of action in the "turnip" session of Congress allowed Truman to continue his attacks on the "do-nothing" Republican-controlled Congress. Truman simply ignored the fact that Dewey's policies were considerably more liberal than most of his fellow Republicans, and instead he concentrated his fire against what he characterized as the conservative, obstructionist tendencies of the unpopular 80th Congress.

Clifford K. Berryman depicts the attitude of the time

Truman toured—and transfixed[citation needed] — much of the nation with his fiery rhetoric, playing to large, enthusiastic crowds. “Give 'em hell, Harry,” was a popular slogan shouted out at stop after stop along the tour. However, the polls and the pundits all held that Dewey's lead was insurmountable, and that Truman's efforts were for naught. Indeed, Truman's own staff considered the campaign a last hurrah. The only person who appears to have considered Truman's campaign to be winnable was the President himself, who confidently predicted victory to anyone and everyone who would listen to him. However, even Truman's own wife had private doubts that her husband could win.

In the final weeks of the campaign, American movie theatres agreed to play two short newsreel-like campaign films in support of the two major-party candidates; each film had been created by its respective campaign organization. The Dewey film, shot professionally on an impressive budget, featured very high production values, but somehow reinforced an image of the New York governor as cautious and distant. The Truman film, hastily assembled on virtually no budget by the perpetually cash-short Truman campaign, relied heavily on public-domain and newsreel footage of the President taking part in major world events and signing important legislation. Perhaps unintentionally, the Truman film visually reinforced an image of the President as engaged and decisive. Years later, historian David McCullough cited the expensive, but lackluster, Dewey film, and the far cheaper, but more effective, Truman film, as important factors in determining the preferences of undecided voters.

In the campaign's final days many newspapers, magazines, and political pundits were so confident of Dewey's impending victory they wrote articles to be printed the morning after the election speculating about the new "Dewey Presidency". Life magazine printed a large photo in its final edition before the election; entitled "Our Next President Rides by Ferryboat over San Francisco Bay", the photo showed Dewey and his staff riding across the city's harbor. Several well-known and influential newspaper columnists, such as Drew Pearson and Joseph Alsop, wrote columns to be printed the morning after the election speculating about Dewey's possible choices for his cabinet. Alistair Cooke, the distinguished writer for the Manchester Guardian newspaper in England, published an article on the day of the election entitled "Harry S. Truman: A Study of a Failure." As Truman made his way to his hometown of Independence, Missouri to await the election returns, not a single reporter traveling on his campaign train thought that he would win.

Results

On election night — November 2 — Dewey, his family, and campaign staff confidently gathered in the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City to await the returns. Truman, aided by the Secret Service, sneaked away from reporters covering him in Kansas City, Missouri and made his way to nearby Excelsior Springs, Missouri, a small resort town. There he took a room in the Elms Hotel, had dinner and a Turkish bath, and went to sleep. As the returns came in Truman took an early lead which he never lost. However, the leading radio commentators, such as H. V. Kaltenborn of NBC, confidently predicted that once the "late returns" came in Dewey would overcome Truman's lead and win. At midnight, Truman awoke and turned on the radio in his room; he heard Kaltenborn announce that, while Truman was still ahead in the popular vote, he couldn't possibly win. Around 4 a.m. Truman awoke again, heard on the radio that his lead was nearly two million votes, and decided to ride back to Kansas City. For the rest of his life, Truman would gleefully mimic Kaltenborn's voice predicting his defeat throughout that election night. Dewey, meanwhile, realized that he was in trouble when early returns from New York and New England showed him running well behind his expected vote total. He was also troubled when the early returns showed that Henry A. Wallace and Strom Thurmond, the two third-party candidates, were not taking as many votes from Truman as had been predicted. Dewey stayed up throughout the night examining the votes as they came in. By 10:30 the next morning he was convinced that he had lost; he then sent a gracious telegram of concession to Truman.

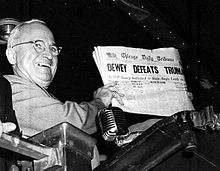

The Chicago Daily Tribune, a pro-Republican newspaper, was so sure of Dewey's victory it printed “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN” on election night as its headline for the following day. A famous photograph taken the next morning showed Truman grinning and holding up a copy of the newspaper. Part of the reason Truman's victory came as such a shock was because of as-yet uncorrected flaws in the emerging craft of public opinion polling. A political theory supported by many pollsters (and largely discredited by the 1948 election) held that voters had already decided who they would support by the time the political conventions ended during the summer, and that few voters were swayed by the campaigning done during the autumn. As a result many pollsters were so confident of Dewey's victory that they simply stopped polling voters weeks before the election, and thus missed a last-minute surge of support for the Democrats. It has been estimated that some 14% of Dewey's supporters — swayed by Truman's claims that an economic depression could return under GOP rule — switched to Truman in the final days before the election. After 1948, pollsters would survey voters until the day before the election: they would also announce their results on television, more or less in real time.

The key states in the 1948 election were Ohio, California, and Illinois. Truman narrowly won all three states by a margin of less than 1%. These three states had a combined total of 78 electoral votes. Had Dewey carried all three states by the same narrow margins, he would have won the election in the electoral college while still losing the popular vote. Had Dewey won any two of the three states the Dixiecrats would have succeeded in their goal of forcing the election into the House. The extreme closeness of the vote in these three states was the major reason why Dewey waited until late on the morning of November 3 to concede. A similarly narrow margin garnered Idaho and Nevada's electoral votes for Truman. Dewey countered by narrowly carrying New York and Pennsylvania, the states with the most electoral votes at the time, as well as Michigan, but it wasn't enough to give him the election. Dewey would always believe that he lost the election because he lost the rural vote in the Midwest, which he had won in the 1944 presidential election; given the effect the dramatic drop in farm commodity prices in the fall of 1948, a year of record farm harvests, may have had on the political mindset of the rural vote that November, Dewey may well have been right.[10]

Truman's victory can be attributed to many factors: his aggressive, populist campaign style; Dewey's complacent, distant approach to the campaign, and his failure to respond to Truman's attacks; the major shift in public opinion from Dewey to Truman during the late stages of the campaign; broad public approval of Truman's foreign policy, notably the Berlin Airlift of that year; and widespread dissatisfaction with the institution Truman labeled as the "do-nothing, good-for-nothing 80th Republican Congress." In addition, after suffering a relatively severe recession in 1946 and 1947 (in which real GDP dropped by 12% and inflation went over 15%), the economy began recovering throughout 1948, thus possibly motivating many voters to give Truman credit for the economic recovery. 1948 was essentially a Democratic year, as the Democrats not only retained the presidency but recaptured both houses of Congress as well. Furthermore, the two third parties did not hurt Truman nearly as much as expected. Thurmond's Dixiecrats carried only four Southern states, a lower total than predicted. The civil rights platform helped Truman win large majorities among black voters in the populous Northern and Midwestern states, and may well have made the difference for Truman in states such as Illinois and Ohio. Wallace's Progressives received only 2.4% of the national popular vote - well below their expected vote total - and Wallace did not take as many liberal votes from Truman as many political pundits had predicted.

The 1948 election marked only the third time in American presidential election history that the winning candidate won despite losing Pennsylvania and New York (the first two times being the 1868 election and the 1916 election - later such elections included 1968, 2000, and 2004). This was also the last time a Democratic candidate won Arizona except for one case: Bill Clinton pulled out a two-point win in 1996. It contrasted with elections from across the world, as Truman was a war leader who managed to win re-election. As of 2008, Truman is the most unpopular leader to win re-election, though his standing with all Americans increased so much in the ensuing decades that he is now remembered by many historians as one of the greatest presidents of the 20th century.

Presidential candidate Party Home state Popular vote Electoral

voteRunning mate Count Pct Vice-presidential candidate Home state Elect. vote Harry S. Truman Democratic(a) Missouri 24,179,347 49.6% 303 Alben W. Barkley Kentucky 303 Thomas E. Dewey Republican(b) New York 21,991,292 45.1% 189 Earl Warren California 189 Strom Thurmond States' Rights Democratic South Carolina 1,175,930 2.4% 39 Fielding L. Wright Mississippi 39 Henry A. Wallace Progressive/American Labor Iowa 1,157,328 2.4% 0 Glen H. Taylor Idaho 0 Norman Thomas Socialist New York 139,569 0.3% 0 Tucker P. Smith Michigan 0 Claude A. Watson Prohibition California 103,708 0.2% 0 Dale Learn Pennsylvania 0 Other 46,361 0.1% — Other — Total 48,793,535 100% 531 531 Needed to win 266 266 Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. 1948 Presidential Election Results. Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections (August 1, 2005).Source (Electoral Vote): Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996. Official website of the National Archives. (August 1, 2005).

Close states

Margin of victory less than 8%:

- Ohio, 0.24%

- California, 0.44%

- Indiana, 0.80%

- Illinois, 0.84%

- New York, 0.99%

- Delaware, 1.28%

- Maryland, 1.39%

- Connecticut, 1.64%

- Michigan, 1.67%

- Iowa, 2.73%

- Idaho, 2.73%

- Nevada, 3.11%

- Oregon, 3.39%

- Pennsylvania, 4.01%

- Wyoming, 4.35%

- New Jersey, 4.39%

- Wisconsin, 4.41%

- South Dakota, 4.80%

Results by state

Harry Truman

DemocraticThomas Dewey

RepublicanStrom Thurmond

DixiecratHenry Wallace

ProgressiveOther State Total State electoral

votes# % electoral

votes# % electoral

votes# % electoral

votes# % electoral

votes# % electoral

votes# Alabama 11 not on ballot 40,930 19.0 - 171,443 79.8 11 1,522 0.7 - 1,085 0.5 - 214,980 AL Arizona 4 95,251 53.8 4 77,597 43.8 - not on ballot 3,310 1.9 - 907 0.5 - 177,065 AZ Arkansas 9 149,659 61.7 9 50,959 21.0 - 40,068 16.5 - 751 0.3 - 1,038 0.5 - 242,475 AR California 25 1,913,134 47.6 25 1,895,269 47.1 - 1,228 0.0 - 190,381 4.7 - 21,526 0.5 - 4,021,538 CA Colorado 6 267,288 51.9 6 239,714 46.5 - not on ballot 6,115 1.2 - 2,120 0.4 - 515,237 CO Connecticut 8 423,297 47.9 - 437,754 49.6 8 not on ballot 13,713 1.6 - 8,754 1.0 - 883,518 CT Delaware 3 67,813 48.8 - 69,588 50.0 3 not on ballot 1,050 0.8 - 622 0.5 - 139,073 DE Florida 8 281,988 48.8 8 194,280 33.6 - 89,755 15.5 - 11,620 2.0 - not on ballot 577,643 FL Georgia 12 254,646 60.8 12 76,691 18.3 - 85,055 20.3 - 1,636 0.4 - 736 0.2 - 418,764 GA Idaho 4 107,370 50.0 4 101,514 47.2 - not on ballot 4,972 2.3 - 960 0.5 - 214,816 ID Illinois 28 1,994,715 50.1 28 1,961,103 49.2 - not on ballot 28,228 0.7 - 3,984,046 IL Indiana 13 807,833 48.8 - 821,079 49.6 13 not on ballot 9,649 0.6 - 17,653 1.1 - 1,656,214 IN Iowa 10 522,380 50.3 10 494,018 47.6 - not on ballot 12,125 1.2 - 9,741 0.9 - 1,038,264 IA Kansas 8 351,902 44.6 - 423,039 53.6 8 not on ballot 4,603 0.6 - 9,275 1.2 - 788,819 KS Kentucky 11 466,756 56.7 11 341,210 41.5 - 10,411 1.3 - 1,567 0.2 - 2,714 0.3 - 822,658 KY Louisiana 10 136,344 32.8 - 72,657 17.5 - 204,290 49.1 10 3,035 0.7 - 10 0.00 - 416,336 LA Maine 5 111,916 42.3 - 150,234 56.7 5 not on ballot 1,884 0.7 - 753 0.3 - 264,787 ME Maryland 8 286,521 48.0 - 294,814 49.4 8 2,476 0.4 - 9,983 1.7 - 2,941 0.5 - 596,735 MD Massachusetts 16 1,151,788 54.7 16 909,370 43.2 - not on ballot 38,157 1.8 - 7,831 0.4 - 2,107,146 MA Michigan 19 1,003,448 47.6 - 1,038,595 49.2 19 not on ballot 46,515 2.2 - 21,051 1.0 - 2,109,609 MI Minnesota 11 692,966 57.2 11 483,617 39.9 - not on ballot 27,866 2.3 - 7,777 0.6 - 1,212,226 MN Mississippi 9 19,384 10.1 - 5,043 2.6 - 167,538 87.2 9 225 0.1 - not on ballot 192,190 MS Missouri 15 917,315 58.1 15 655,039 41.5 - 42 0.0 - 3,998 0.3 - 2,234 0.1 - 1,578,628 MO Montana 4 119,071 53.1 4 96,770 43.2 - not on ballot 7,313 3.3 - 1,124 0.5 - 224,278 MT Nebraska 6 224,165 45.9 - 264,774 54.2 6 not on ballot 1 0.0 - 488,940 NE Nevada 3 31,291 50.4 3 29,357 47.3 - not on ballot 1,469 2.4 - not on ballot 62,117 NV New Hampshire 4 107,995 46.7 - 121,299 52.4 4 7 0.0 - 1,970 0.9 - 169 0.1 - 231,440 NH New Jersey 16 895,455 45.9 - 981,124 50.3 16 not on ballot 42,683 2.2 - 30,293 1.6 - 1,949,555 NJ New Mexico 4 105,464 56.4 4 80,303 42.9 - not on ballot 1,037 0.6 - 259 0.1 - 187,063 NM New York 47 2,780,204 45.0 - 2,841,163 46.0 47 not on ballot 509,559 8.3 - 46,411 0.8 - 6,177,337 NY North Carolina 14 459,070 58.0 14 258,572 32.7 - 69,652 8.8 - 3,915 0.5 - not on ballot 791,209 NC North Dakota 4 95,812 43.4 - 115,139 52.2 4 374 0.2 - 8,391 3.8 - 1,000 0.5 - 220,716 ND Ohio 25 1,452,791 49.5 25 1,445,684 49.2 - not on ballot 37,596 1.3 - not on ballot 2,936,071 OH Oklahoma 10 452,782 62.7 10 268,817 37.3 - not on ballot 721,599 OK Oregon 6 243,147 46.4 - 260,904 49.8 6 not on ballot 14,978 2.9 - 5,051 1.0 - 524,080 OR Pennsylvania 35 1,752,426 46.9 - 1,902,197 50.9 35 not on ballot 55,161 1.5 - 25,364 0.7 - 3,735,148 PA Rhode Island 4 188,736 57.6 4 135,787 41.4 - not on ballot 2,619 0.8 - 560 0.2 - 327,702 RI South Carolina 8 34,423 24.1 - 5,386 3.8 - 102,607 72.0 8 154 0.1 - 1 0.0 - 142,571 SC South Dakota 4 117,653 47.0 - 129,651 51.8 4 not on ballot 2,801 1.1 - not on ballot 250,105 SD Tennessee 12 270,402 49.1 11 202,914 36.9 - 73,815 13.4 1 1,864 0.3 - 1,288 0.2 - 550,283 TN Texas 23 824,235 66.0 23 303,467 24.2 - 113,776 9.1 - 3,920 0.3 - 4,179 0.3 - 1,249,577 TX Utah 4 149,151 54.0 4 124,402 45.0 - not on ballot 2,679 1.0 - 73 0.0 - 276,305 UT Vermont 3 45,557 36.9 - 75,926 61.5 3 not on ballot 1,279 1.0 - 620 0.5 - 123,382 VT Virginia 11 200,786 47.9 11 172,070 41.0 - 43,393 10.4 - 2,047 0.5 - 960 0.2 - 419,256 VA Washington 8 476,165 52.6 8 386,315 42.7 - not on ballot 31,692 3.5 - 10,887 1.2 - 905,059 WA West Virginia 8 429,188 57.3 8 316,251 42.2 - not on ballot 3,311 0.4 - not on ballot 748,750 WV Wisconsin 12 647,310 50.7 12 590,959 46.3 - not on ballot 25,282 2.0 - 13,249 1.0 - 1,276,800 WI Wyoming 3 52,354 51.6 3 47,947 47.3 - not on ballot 931 0.9 - 193 0.2 - 101,425 WY TOTALS: 531 24,179,347 49.6 303 21,991,292 45.1 189 1,175,930 2.4 39 1,157,328 2.4 - 289,638 0.6 - 48,793,535

TO WIN: 266 (a) In New York, the Truman vote was a fusion of the Democratic and Liberal slates. There, Truman obtained 2,557,642 votes on the Democratic ticket and 222,562 votes on the Liberal ticket.[11]

(b) In Mississippi, the Dewey vote was a fusion of the Republican and Independent Republican slates. There, Dewey obtained 2595 votes on the Republican ticket and 2448 votes on the Independent Republican ticket.[11]See also

References

- ^ "The Nation: Independence Day". Time. 1948-11-08. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,853326,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ "The Nation: The Will of the People". Time. 1952-11-10. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,817173,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ "National Affairs: Tke Corruption Issue: A Pandora's Box". Time. 1956-09-24. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,867099-3,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ http://jcgi.pathfinder.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,887493,00.html

- ^ Our Campaigns - US President - R Primaries Race - Feb 01, 1948

- ^ "Truman Wrote of '48 Offer to Eisenhower" The New York Times, July 11,2003.

- ^ Hugh Alvin Bone, American Politics and the Party System, p262 (McGraw-Hill 1955).

- ^ a b http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1366

- ^ Donaldson, Gary A. (1999). Truman Defeats Dewey. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 173. ISBN 0813120756. Quoting The Courier-Journal, November 18, 1948.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b "Statistics of the Presidential and Congressional Election of November 2, 1948" (PDF). Official website of the Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. http://clerk.house.gov/member_info/electionInfo/1948election.pdf. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

Further reading

- Bass, Jack; Thompson, Marilyn W. (2005). Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 1586482971

- Divine, Robert A. (1972). "The Cold War and the Election of 1948". Journal of American History (Organization of American Historians) 59 (1): 90–110. doi:10.2307/1888388. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1888388

- Donaldson, Gary A. (1999). Truman Defeats Dewey. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813120756.

- Gullan, Harold I. (1998). The Upset That Wasn't: Harry S. Truman and the Crucial Election of 1948. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1566632064.

- Karabell, Zachary (2001). The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0375400869.

- Pietrusza, David W. (2011). 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America. New York: Union Square Press (Sterling Publishing). ISBN 140276748X.

- Reinhard, David W. (1983). The Republican Right since 1945. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813114845.

- Smith, Richard Norton (1984). Thomas E. Dewey and His Times. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 067141741X

- Schmidt, Karl M. (1960). Henry A. Wallace, Quixotic Crusade 1948. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815600208.

- Sitkoff, Harvard. "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics," Journal of Southern History Vol. 37, No. 4 (Nov., 1971), pp. 597-616 in JSTOR

Primary sources

- Mosteller, Frederick (1949). The Pre-Election Polls of 1948: Report to the Committee on Analysis of Pre-Election Polls and Forecasts. New York: Social Science Research Council.

- Neal, Steve (2003). Miracle of '48: Harry Truman's Major Campaign Speeches & Selected Whistle-Stops. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0809325578.

External links

- 1948 popular vote by counties

- 1948 State-by-state Popular vote

- How close was the 1948 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

United States presidential elections

United States presidential elections1788 · 1792 · 1796 · 1800 · 1804 · 1808 · 1812 · 1816 · 1820 · 1824 · 1828 · 1832 · 1836 · 1840 · 1844 · 1848 · 1852 · 1856 · 1860 · 1864 · 1868 · 1872 · 1876 · 1880 · 1884 · 1888 · 1892 · 1896 · 1900 · 1904 · 1908 · 1912 · 1916 · 1920 · 1924 · 1928 · 1932 · 1936 · 1940 · 1944 · 1948 · 1952 · 1956 · 1960 · 1964 · 1968 · 1972 · 1976 · 1980 · 1984 · 1988 · 1992 · 1996 · 2000 · 2004 · 2008 · 2012

Electoral College · Electoral vote changes · Electoral votes by state · Results by Electoral College margin · Results by popular vote margin · Results by state · Voter turnout · Presidential primaries · Presidential nominating conventionsSee also: House elections · Senate elections · Gubernatorial elections United States presidential election, 1948 Democratic Party

Convention · PrimariesNominee: Harry Truman

VP nominee: Alben W. Barkley

Candidates: Harley M. Kilgore · Richard Russell, Jr. · Henry A. WallaceRepublican Party

Convention · PrimariesNominee: Thomas Dewey

VP nominee: Earl Warren

Candidiates: Riley A. Bender · Herbert E. Hitchcock · Joseph William Martin, Jr. · Edward Martin · Leverett Saltonstall · Harold Stassen · Arthur H. Vandenberg · Robert TaftState's Rights Democratic Party Other third party and independent candidates Prohibition Party Nominee: Claude A. WatsonProgressive Party Socialist Party of America Nominee: Norman Thomas

VP nominee: Tucker P. SmithSocialist Workers Party Nominee: Farrell DobbsIndependents and other candidates: Other 1948 elections: House · Senate Notable third party performances in United States elections (At least 5% of the vote) Presidential (Since 1832) Senatorial (Since 1990) Virginia 1990 · Alaska 1992 · Arizona 1992 · Hawaii 1992 · Ohio 1992 · Arizona 1994 · Minnesota 1994 · Ohio 1994 · Vermont 1994 · Virginia 1994 · Alaska 1996 · Minnesota 1996 · Arizona 2000 · Massachusetts 2000 · Minnesota 2000 · Alaska 2002 · Kansas 2002 · Massachusetts 2002 · Mississippi 2002 · Oklahoma 2002 · Virginia 2002 · Oklahoma 2004 · Connecticut 2006 · Indiana 2006 · Maine 2006 · Vermont 2006 · Arkansas 2008 · Minnesota 2008 · Oregon 2008 · Florida 2010 · Indiana 2010 · South Carolina 2010 · Utah 2010Gubernatorial (Since 1990) Alaska 1990 · Connecticut 1990 · Kansas 1990 · Maine 1990 · New York 1990 · Oklahoma 1990 · Oregon 1990 · Utah 1992 · West Virginia 1992 · Alaska 1994 · Connecticut 1994 · Hawaii 1994 · Maine 1994 · New Mexico 1994 · Oklahoma 1994 · Pennsylvania 1994 · Rhode Island 1994 · Vermont 1994 · Alaska 1998 · Maine 1998 · Minnesota 1998 · New York 1998 · Pennsylvania 1998 · Rhode Island 1998 · Kentucky 1999 · New Hampshire 2000 · Vermont 2000 · Arizona 2002 · California 2002 · Maine 2002 · Minnesota 2002 · New Mexico 2002 · New York 2002 · Oklahoma 2002 · Wisconsin 2002 · Alaska 2006 · Illinois 2006 · Maine 2006 · Massachusetts 2006 · Minnesota 2006 · Texas 2006 · Louisiana 2007 · Vermont 2008 · New Jersey 2009 · Colorado 2010 · Idaho 2010 · Maine 2010 · Massachusetts 2010 · Minnesota 2010 · Rhode Island 2010 · Wyoming 2010Portal:Politics - Third party (United States) - Third party officeholders in the United States - Third party United States House of Representatives Categories:- United States presidential election, 1948

- History of the United States (1945–1964)

- Presidency of Harry S. Truman

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.