- Dvorak Simplified Keyboard

-

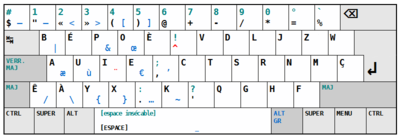

Typing a text excerpt at 115 WPM with the Canadian French Dvorak keyboard layout.

The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard is a keyboard layout patented in 1936 by Dr. August Dvorak (pronounced /dᵊˈvɔræk/ (

listen) d-vor-ak) and his brother-in-law, Dr. William Dealey. Over the years several slight variations were designed by the team led by Dvorak or by ANSI. These variations have been collectively or individually also called the Simplified Keyboard or American Simplified Keyboard but they all have come to be commonly known as the Dvorak keyboard or Dvorak layout. Dvorak proponents claim the Dvorak layout uses less finger motion, increases typing rate, and reduces errors compared to the standard QWERTY[1] keyboard. This reduction in finger distance traveled was originally purported to permit faster rates of typing, and also in later years, it was purported to reduce repetitive strain injuries[2] including carpal tunnel syndrome.[citation needed]

listen) d-vor-ak) and his brother-in-law, Dr. William Dealey. Over the years several slight variations were designed by the team led by Dvorak or by ANSI. These variations have been collectively or individually also called the Simplified Keyboard or American Simplified Keyboard but they all have come to be commonly known as the Dvorak keyboard or Dvorak layout. Dvorak proponents claim the Dvorak layout uses less finger motion, increases typing rate, and reduces errors compared to the standard QWERTY[1] keyboard. This reduction in finger distance traveled was originally purported to permit faster rates of typing, and also in later years, it was purported to reduce repetitive strain injuries[2] including carpal tunnel syndrome.[citation needed]Although the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard (“DSK”) has failed to displace the QWERTY keyboard, it has become easier to access in the computer age, being compatible with all major operating systems (such as GNU/Linux, Mac OS X, Microsoft Windows and BSD) in addition to the standard QWERTY layout. Most major operating systems have the option of toggling to the Dvorak layout.[3] It is also supported at the hardware level by some high-end ergonomic keyboards.[4]

Contents

Overview

The Dvorak layout was designed to replace the QWERTY keyboard layout (the de facto standard keyboard layout, so named for the starting letters in the top row), in which keys are arranged to avoid mechanical jams on the first generation of economically successful typewriters.[5] The original QWERTY keyboard suffers from many problems that Dvorak himself identified:

- Many common letter combinations require awkward finger motions.

- Many common letter combinations are typed with the same finger.

- Many common letter combinations require a finger to jump over the home row.

- Many common letter combinations are typed with one hand while the other sits idle.

- Most typing is done with the left hand, which for most people is the weaker hand.

- Many common letter combinations are typed by adjacent fingers, which is slower than using other fingers.

- About 30% of typing is done on the lower row, which is the slowest and most difficult row to reach.[6]

- About 52% of keyboard strokes are done in the top row, requiring the fingers to travel away from the home row most of the time.[7]

Dvorak studied letter frequencies and the physiology of people’s hands and created a layout to alleviate the problems he identified with the QWERTY layout. The layout he created adheres to these principles:

- Letters should be typed by alternating between hands (which makes typing more rhythmic, increases speed, reduces error, and reduces fatigue).

- For maximum speed and efficiency, the most common letters and digraphs should be the easiest to type. This means that they should be on the home row, which is where the fingers rest, and under the strongest fingers (Thus, about 70% of keyboard strokes on the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard are done on the home row).

- The least common letters should be on the bottom row, which is the hardest row to reach.

- The right hand should do more of the typing, because most people are right-handed.

- Digraphs should not be typed with adjacent fingers.

- Stroking should generally move from the edges of the board to the middle. An observation of this principle is that, for many people, when tapping fingers on a table, it is easier going from little finger to index than vice versa. This motion on a keyboard is called inboard stroke flow.[8]

The Dvorak layout is intended for the English language. In other European languages, letter frequencies, letter sequences, and digraphs differ from English. Also, many languages have letters that do not occur in English. For non-English use, these differences lessen the supposed advantages of the original Dvorak keyboard. However, the Dvorak principles have been applied to the design of keyboards for these other languages.

The layout was completed in 1932 and was granted U.S. Patent 2,040,248 in 1936.[9] The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) designated the Dvorak keyboard as an alternative standard keyboard layout in 1982; the standard is X3.207:1991 (previously X4.22-1983), “Alternate Keyboard Arrangement for Alphanumeric Machines”. The original ANSI Dvorak layout was available as a factory-supplied option on the original IBM Selectric typewriter.[specify]

Some researchers challenge the established view that the Dvorak layout is ergonomically superior to the QWERTY one, and hold that QWERTY emerged through a quite rigorous process of competition and eventual acceptance in the marketplace.[10] However, the findings of these researchers themselves have been challenged. For instance, even though QWERTY did emerge from a process of competition, at the time few, if any, other typing machines had keyboards; therefore the QWERTY keyboard layout itself was subject to very little, if any, competition.[11]

In 1984, the Dvorak layout had an estimated 100,000 users.[12]

Comparison of the QWERTY and Dvorak layouts

Keyboard strokes

Touch typing requires a typist to rest their hands in the home row (QWERTY row starting with "ASDF"). The more strokes there are in the home row, the less movement the fingers must do, thus allowing a typist to type faster, more accurately, and with less strain to the hand and fingers. Motion picture studies prove not only that typing is done fastest in the home row, but also typing is the slowest on the bottom row. If the fingers must move, it is easier to move them up to the top row (QWERTY row starting with "QWERTY") rather than down to the bottom row (QWERTY row starting with "ZXCV").

Key stroke distribution Row QWERTY Dvorak Top 52% 22% Home 32% 70% Bottom 16% 8% It is notable that the vast majority of the Dvorak layout's key strokes (70%) are done in the home row (the easiest row to type because the fingers rest there). In addition, the Dvorak layout requires the fewest strokes on the bottom row (the most difficult row to type). On the other hand, QWERTY requires typists to move their fingers to the top row for a majority of strokes and has only 32% of the strokes done in the home row.[13]

Because the Dvorak layout concentrates the vast majority of key strokes to the home row, the Dvorak layout uses about 63% of the finger motion required by QWERTY, thus making the Dvorak layout more ergonomic.[14] Because the Dvorak layout requires less finger motion from the typist compared to QWERTY, many users with repetitive strain injuries have reported that switching from QWERTY to Dvorak alleviated or even eliminated their repetitive strain injuries.[15][16]

The typing loads between hands differs for each of the keyboard layouts. On QWERTY keyboards, 56% of the typing strokes are done by the left hand. As the left hand is weaker for the majority of people, the Dvorak keyboard puts the more often used keys on the right hand side, thereby having 56% of the typing strokes done by the right hand.[13]

Awkward strokes

Awkward strokes are undesirable because they slow down typing, increase typing errors, and increase finger strain. Hurdling is an awkward stroke requiring a single finger to jump directly from one row, over the home row to another row (e.g., typing “minimum” (which often comes out as "minimun" or "mimimum") on the QWERTY keyboard).[17] In the English language, there are about 1,200 words that require a hurdle on the QWERTY layout. In contrast, there are few words requiring a hurdle on the Dvorak layout and even fewer requiring a double hurdle.[17][18]

Hand alternation

Alternating hands while typing is a desirable trait because while one hand is typing a letter, the other hand can get in position to type the next letter. Thus, a typist may fall into a steady rhythm and type quickly. However, when a string of letters is done with the same hand, the chances of stuttering are increased and a rhythm can be broken, thus decreasing speed and increasing errors and fatigue. The QWERTY layout has more than 3,000 words that are typed on the left hand alone and about 300 words that are typed on the right hand alone (the aforementioned word "minimum" is a right-hand-only word). In contrast, with the Dvorak layout, only a few words are typed using only the left hand and even fewer with the right hand.[13] This is because a syllable requires at least one vowel, and all the vowels (and "y") are on the left side.

Standard keyboard

QWERTY enjoys advantages over the Dvorak layout due to its position as the de facto standard keyboard:

- Keyboard shortcuts in most major operating systems, including Windows, are designed for QWERTY users and can be awkward for Dvorak users, such as Ctrl-C (Copy) and Ctrl-V (Paste).

- Some public computers (such as in libraries) will not allow users to change the keyboard to the Dvorak layout

- Some standardized exams will not allow test takers to use the Dvorak layout (e.g. Graduate Record Examination)

- Games can prove nearly impossible to play with the default keyboard mapping, especially those which use W,A,S,D as controls.

- People who can touch type with a QWERTY keyboard may be less productive with alternative layouts even if these are more optimal[19]. Re-learning touch typing is an investment, with average level courses costing $ 320 or about, not counting the time of the student, and these are still not the true professional studies[20].

History

August Dvorak was an educational psychologist and professor of education at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.[21] Dvorak became interested in the keyboard layout while serving as an advisor to Gertrude Ford, who was writing her master’s thesis on typing errors. Touch typing had come into wide use by that time, so when Dvorak studied the QWERTY layout he concluded that the QWERTY layout needed to be replaced. Dvorak was joined by his brother-in-law William Dealey, who was a professor of education at the then North Texas State Teacher's College in Denton, Texas.

Dvorak and Dealey’s objective was to scientifically design a keyboard to decrease typing errors, speed up typing, and lessen typer fatigue. They engaged in extensive research while designing their keyboard layout. In 1914 and 1915, Dealey attended seminars on the science of motion and later reviewed slow-motion films of typists with Dvorak. Dvorak and Dealey meticulously studied the English language, researching the most used letters and letter combinations. They also studied the physiology of the hand. The result in 1932 was the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard.[22]

In 1933, Dvorak started entering typists trained on his keyboard into the International Commercial Schools Contest, which were typing contests sponsored by typewriter manufacturers consisting of professional and amateur contests. The professional contests had typists sponsored by typewriter companies to advertise their machines. Ten times from 1934–41, Dvorak’s typists won first in their class events. In the 1935 contest alone, nine Dvorak typists won twenty awards. Dvorak typists were so successful that in 1937 the Contest Committee barred Dvorak’s typists for being “unfair competition” until Dvorak protested. In addition, QWERTY typists did not want to be placed near Dvorak typists because QWERTY typists were disconcerted by the noise produced from the fast typing speeds made by Dvorak typists.[23]

In the 1930s, the Tacoma, Washington, school district ran an experimental program in typing to determine whether to hold Dvorak layout classes. The experiment used 2,700 students to learn the Dvorak layout, and the district found that the Dvorak layout students learned the keyboard in one-third the time it took to learn QWERTY. However, a new school board was elected and chose to close the Dvorak layout classes.[23]

Writer Barbara Blackburn was the fastest English language typist in the world, according to The Guinness Book of World Records. Using the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, she was able to maintain 150 words per minute (wpm) for 50 minutes, and 170 wpm for shorter periods. She has been clocked at a peak speed of 212 wpm. Blackburn, who failed her QWERTY typing class in high school, first encountered the Dvorak keyboard in 1938, quickly learned to achieve very high speeds, and occasionally toured giving speed-typing demonstrations during her secretarial career. Blackburn died in April 2008.[24]

Original Dvorak layout

Over the decades, symbol keys were shifted around the keyboard leading to variations in the Dvorak layout. In 1982, the American National Standards Institute (“ANSI”) implemented a standard for the Dvorak layout known as ANSI X4.22-1983. This standard gave the Dvorak layout official recognition as an alternative to the QWERTY keyboard.[25]

The layout standardized by the ANSI differs from the original or “classic” layout devised and promulgated by Dvorak. Indeed, the layout promulgated publicly by Dvorak differed slightly from the layout for which Dvorak & Dealey applied for a patent in 1932—most notably in the placement of Z. Today’s keyboards have more keys than the original typewriter did, and other significant differences existed:

- The numeric keys of the classic Dvorak layout are ordered: 7 5 3 1 9 0 2 4 6 8

- In the classic Dvorak layout, the question mark key [?] is in the leftmost position of the upper row, while the slash key [/] is in the rightmost position of the upper row.

- The following symbols share keys (the second symbol being printed when the SHIFT key is pressed):

- colon [:] and question mark [?]

- ampersand [&] and slash [/].

Modern U.S. keyboard layouts almost always place semicolon and colon together on a single key, and slash and question mark together on a single key. Thus, if the keycaps of a modern keyboard are rearranged so that the unshifted symbol characters match the classic Dvorak layout then, sensibly, the result is the ANSI layout.

Modern operating systems

The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard (“DSK”) is included with all major operating systems (such as Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, Linux and BSD). Changing a computer running on a major operating system to the Dvorak layout can be done within 30 seconds.[3]

Early PCs

Although some word processors could simulate alternative keyboard layouts through software, this was application-specific; if more than one program was commonly used (e.g., a word processor and a spreadsheet), the user could be forced to switch layouts depending on the application. Occasionally, stickers were provided to place over the keys for these layouts.

However, IBM-compatible PCs used an active, “smart” keyboard, where the keyboard was actually a peripheral device (powered by the keyboard port). Striking a key generated a key “code”, which was sent to the computer. Thus, changing to an alternative keyboard layout was most easily accomplished by simply buying a keyboard with the new layout. Because the key codes were generated by the keyboard itself, all software would respond accordingly. In the mid- to late-1980s, a small cottage industry for replacement PC keyboards arose; although most of these were concerned with keyboard “feel” and/or programmable macros, there were several with alternative layouts, such as Dvorak.

Amiga

Some Amiga operating systems can modify the keyboard layout by opening up the keyboard input preference, and selecting "Dvorak". Earlier Amiga systems also came with the Dvorak keymap available on the "Extras" disk that came with the computer. By copying the keymap to the Workbench disk, editing the startup scripts, and then rebooting, Dvorak was usable in many Workbench application programs.

Windows

According to Microsoft, versions of the Windows operating system including Windows 95, Windows NT 3.51 and higher have shipped with support for the U.S. Dvorak layout.[26] Free updates to use the layout on earlier Windows versions are available for download from Microsoft.

Earlier versions, such as DOS 6.2/Windows 3.1, included four keyboard layouts: QWERTY, two-handed Dvorak, right-hand Dvorak, and left-hand Dvorak.

In May 2004 Microsoft published an improved version of its Keyboard Layout Creator (MSKLC version 1.3[27] – current version is 1.4[28]) that allows anyone to easily create any keyboard layout desired, thus allowing the creation and installation of any international Dvorak keyboard layout such as Dvorak Type II (for German), Svorak (for Swedish) etc.

Another advantage of the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator over third-party tools for installing an international Dvorak layout is that it allows creation of a keyboard layout that automatically switches to standard (QWERTY) after pressing the two hotkeys (SHIFT and CTRL).

Unix-based systems

Many operating systems based on UNIX, including OpenBSD, FreeBSD, NetBSD, OpenSolaris, Plan 9, and most Linux distributions, can be configured to use the U.S. Dvorak layout and a handful of variants. However, all current Unix-like systems with X.Org and appropriate keymaps installed (and virtually all systems meant for desktop use include them) are able to use any QWERTY-labeled keyboard as a Dvorak one without any problems or additional configuration. This removes the burden of producing additional keymaps for every variant of QWERTY provided. Runtime layout switching is also possible.

Apple computers

Apple had Dvorak advocates since the company’s early (pre-IPO) days. Several engineers devised hardware and software to remap the keyboard, which were used inside the company and even sold commercially.

Apple II

The Apple II had a keyboard ROM that translated keystrokes into characters. The ROM contained both QWERTY and Dvorak layouts, but the QWERTY layout was enabled by default. A modification could be made by pulling out the ROM, bending up four pins, soldering a resistor between two pins, soldering two others to a pair of wires connected to a DIP switch, which was installed in a pre-existing hole in the back of the machine, then plugging the modified ROM back in its socket. The “hack” was reversible and did no damage. By flipping a switch on the machine’s back panel, the user could switch from one layout to the other. This modification was entirely unofficial but was inadvertently demonstrated at the 1984 Comdex show, in Las Vegas, by an Apple employee whose mission was to demonstrate Apple Logo II. The employee had become accustomed to the Dvorak layout and brought the necessary parts to the show, installed them in a demo machine, then did his Logo demo. Viewers, curious that he always reached behind the machine before and after allowing other people to type, asked him about the modification. He spent as much time explaining the Dvorak keyboard as explaining Logo.[citation needed]

Apple brought new interest to the Dvorak layout with the Apple IIc, which had a mechanical switch above the keyboard whereby the user could switch back and forth between the QWERTY layout and the Dvorak layout: this was the most official version of the IIe Dvorak mod. The IIc Dvorak layout was even mentioned in 1984 ads, which stated that the World's Fastest Typist, Barbara Blackburn, had set a record on an Apple IIc with the Dvorak layout.

The Dvorak layout was also selectable using the built-in control panel applet on the Apple IIGS.

Apple III

The Apple III used a keyboard-layout file loaded from a floppy disk: the standard system-software package included QWERTY and Dvorak layout files. Changing layouts required restarting the machine.

Apple Lisa

The technical documentation available to third-party developers does not mention keyboard mapping, though it was purportedly available through undocumented interfaces.[citation needed].

Mac OS

iBook with alpha and punctuation keys manually rearranged to the Dvorak layout

In its early days, the Macintosh could be converted to the Dvorak layout by making changes to the “System” file: this was not easily reversible and required restarting the machine. This modification was highly unofficial, but it was comparable to many other user-modifications and customizations that Mac users made. Using the “resource editor”, ResEdit, users could create keyboard layouts, icons, and other useful items. A few years later, a third-party developer offered a utility program called MacKeymeleon, which put a menu on the menu bar that allowed on-the-fly switching of keyboard layouts. Eventually, Apple Macintosh engineers built the functionality of this utility into the standard System Software, along with a few layouts: QWERTY, Dvorak, French (AZERTY), and other foreign-language layouts.

Since about 1998, beginning with Mac OS 8.6, Apple has included the Dvorak layout. It can be activated with the Keyboard Control Panel and selecting "Dvorak". The setting is applied once the Control Panel is closed out. Keyboard layouts can be switched back and forth by firmly pressing ⌘ + Space or ⌘ + Option + Space. Apple also includes a Dvorak variant they call “Dvorak – Qwerty ⌘”. With this layout, the keyboard temporarily becomes QWERTY when the Command (⌘/Apple) key is held down. By keeping familiar keyboard shortcuts like “close” or “copy” on the same keys as ordinary QWERTY, this lets some people use their well-practiced muscle memory and may make the transition easier. Mac OS and subsequently Mac OS X allows additional “on-the-fly” switching between layouts: a menu-bar icon (by default, a national flag that matches the current language, a ‘DV’ represents Dvorak and a ‘DQ’ represents Dvorak – Qwerty ⌘) brings up a drop-down menu, allowing the user to choose the desired layout. Subsequent keystrokes will reflect the choice, which can be reversed the same way.

Mobile phones and PDAs

A number of mobile phones today are built with either full QWERTY keyboards or software implementations of them on a touch screen. Sometimes the keyboard layout can be changed by means of a freeware third-party utility, such as Hacker's Keyboard for Android, AE Keyboard Mapper for Windows Mobile, or KeybLayout for Symbian OS.

The RIM BlackBerry lines support only QWERTY and its localized variants AZERTY and QWERTZ. Apple's iOS 4.0 supports external Dvorak keyboards.

Controversy

Through its history the Dvorak layout and the benefits it claims have come under much scrutiny. Many claim that the experiments determining its superiority in terms of speed of typing are biased, with the most famous being conducted by Dvorak himself, and insufficiently rigorous.[29] One major test in 1956 conducted by the U.S. General Service Administration found Dvorak no more efficient than QWERTY.[30]

Resistance to adoption

Although the Dvorak layout is the only other keyboard layout registered with ANSI and is provided with all major operating systems, attempts to convert universally to the Dvorak layout have not succeeded. The failure of the Dvorak layout to displace the QWERTY layout has been the subject of some studies.[31][32][33]

In 1956, a General Services Administration study by Earle Strong, which included an experiment involving ten experienced government typists, concluded that Dvorak training would never be able to amortize its costs.[19] The study was a large obstacle for the wide adoption of Dvorak for many firms and government agencies.[34] One criticism of the experiment is that it did not involve any beginning typists; however, Liebowitz notes that it parallels the decision that a real firm or government agency would need to make: Is it worthwhile to retrain its present typists?[35] A second critique of the study points out that the Dvorak typists were not given adequate time to reach their potential competence, and what promise had been demonstrated by the Dvorak typists was ignored by the researchers.[36] Strong's objectivity with regard to the Dvorak keyboard has also been questioned. Seven years before the study began Strong wrote “I have developed a great deal of material on how to get this increased production on the part of typists on the standard keyboard. Consequently, I am not in favor of purchasing new keyboards and retraining typists on the new keyboard. ... I strongly feel that the present keyboard has not been fully exploited, and I am out to exploit it to its utmost in opposition to the change to new keyboards.” Furthermore, there is evidence of a strained business relationship between Strong and Dvorak.[37] When researchers had asked Strong for the data to his study, it was found that Strong had destroyed it.[37][Full citation needed]

However, in considering resistance to the adoption of the Dvorak layout, different segments of the market differ in the extent, nature, and motivation of their resistance. Furthermore, the influence of these factors on the different segments of the market has changed over time, following changes in technology and awareness of Dvorak as an alternative keyboard layout. Factors against adoption of the Dvorak layout have included the following:

- Dvorak introduced his layout during the Great Depression, a time when businesses and people did not have the resources to invest in the new layout.[38]

- With World War II came the conversion of typewriter manufacturing plants into small arms plants, thus halting production of new typewriters (including the Dvorak Layout).[39]

- The publication of Earle Strong's aforementioned report.[39]

- Failure to achieve the general population's awareness that the Dvorak layout existed. This improved somewhat following the Guinness Book of Records 1985 publication of Barbara Blackburn’s achievement of 212 wpm using a Dvorak keyboard,[40] and again in the mid-1990s when computer operating systems began to incorporate the Dvorak layout as an option.

- Failure to overcome an investment in competence in the QWERTY layout made by a large number of typists and typist trainers prior to the general availability of the Dvorak layout. This investment has proved the most powerful influence up until the 1990s. Typing training in schools and secretarial colleges is almost always done on the QWERTY layout both because it conforms with the expectation of industry and because it is the layout with which most teachers or trainers are already familiar.

- A reduction in efficiency while learning the Dvorak layout further impedes its adoption by typists already competent with QWERTY, and the organizations that employ them.

- Failure to persuade large typewriter manufacturers to produce significant volumes of typewriters equipped with Dvorak layouts.

- Converting standard mechanical typewriters to Dvorak (or any alternative, e.g. international layout) was often impractical and excessively expensive, so switching to Dvorak usually required a new, dedicated machine[citation needed]. A notable exception was the popular IBM Selectric typewriter, which used a single spherical typing element rather than individual character hammers; it could easily be converted by replacing the QWERTY typing element with a Dvorak equivalent.

This problem was effectively eliminated with the advent of PCs, where computer programs can change the character produced when a particular key is pressed. This capacity benefited not only Dvorak typists, but those who typed in languages other than English. With early computers, this required the contents of the character-generator ROM to be changed, but with subsequent designs only a table in memory or the disk file storing this table needed to be changed. By the mid 1990s the Dvorak layout was a standard option on most computer systems. - Incompatibility between the two keyboard layouts on computers, where keys are assigned additional functions within software programs. In some cases related additional functions are assigned to keys that are physically proximate on the QWERTY layout, but not so in the Dvorak layout; for example, the Unix text editor vi uses the keys H, J, K and L to cause movement to the left, down, up, and right, respectively. With a QWERTY layout, these keys are all together under the right-hand home row, but with the Dvorak layout they are no longer neatly together. In many video games, keys W, A, S and D are used for arrow movements (their inverse-T arrangement on a QWERTY layout mirrors the arrangement of the cursor keys). In the Dvorak layout, this is no longer true, although most video games allow keys to be remapped, and many will automatically recognize the normal key locations regardless. Common computer keyboard shortcuts for undo, cut, copy and paste operations are Ctrl (or Command) + Z, X, C, and V respectively; conveniently located in the same row in the QWERTY layout, but not on a Dvorak layout. While some applications do compensate for this, these issues do add a layer of complexity to using the many computer applications that do not.

- Some confusion regarding which of the keyboard layouts designed by August Dvorak is the “real” Dvorak layout. This arose in part due to the existence of, in addition to the standard layout, layouts for left-handed (only) and right-handed (only) use. Also, while Dvorak specified a particular layout for the number sequence at the top of the keyboard, most implementations of the Dvorak layout retain the ‘1,2,3...9,0’ arrangement; most people who want to type numbers quickly will use the numeric keypad rather than the top row.

An appreciation of the strength of the resistance factors (particularly the investment in typewriter manufacturing)[citation needed] suggests that the Dvorak layout would need to have been significantly superior to the QWERTY layout in order for the former to displace the latter in widespread use in the past. If the Dvorak layout is inherently at least as efficient as, or more efficient than, the QWERTY layout, then one might expect to see an increasing rate of use as resistance factors (such as lack of awareness, non-programmable machines, and one-style formal training) become less powerful. There are no surveys or studies looking at the rate of use of the Dvorak layout over time.

A discussion of the Dvorak layout is sometimes used as an exercise by management consultants to illustrate the difficulties of change. The Dvorak layout is often used[by whom?] as a standard example of network effects, particularly in economics textbooks.

Alternatives

Because of the radical differences between QWERTY and Dvorak, existing typists find that it takes considerable time and effort to make the change. As a consequence, some attempts have been made to design alternative layouts that follow the principles involved in the Dvorak keyboard layout but preserve many of the QWERTY key positions, thereby making it easier for users to make the transition. Programs such as the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator[41] and KbdEdit[42] allow this to be done very easily. One such popular variant is the Colemak keyboard layout.[43]

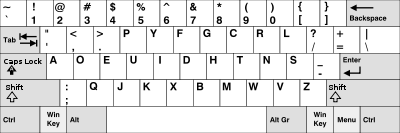

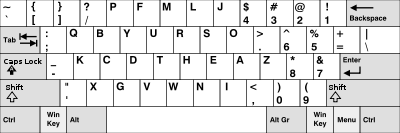

One-handed versions

During the 1960s, Dvorak applied a similar approach of minimizing distance traveled when he designed quite different arrangements for touch-typing with only the left hand or with only the right hand. This can provide increased accessibility to single-handed users who might struggle with excessive lateral hand movement when using two-handed keyboards. Note that the right-handed and left-handed Dvorak layouts not only differ from each other dramatically, but also differ from two-handed Dvorak layout quite dramatically as well. Some users with full use of both hands enjoy the ability to simultaneously type with only a single hand while concurrently controlling a mouse with the other hand, or in the case of police officers, operating vehicular controls with their left hand while touch-typing with their right hand on a dashboard-mounted laptop computer. The arrangements have been designed for each hand to minimize distance traveled by fingers as well as to minimize lateral distance traveled by the hand as a whole. Note that the hand is intended to rest near the center of the keyboard in order to reach the entire keyboard, eliminating the need for the split ergonomic keyboard layout.

Note that the left-handed Dvorak and right-handed Dvorak keyboard layouts are substantially mirror images of each other, with the exception of keys that are wider than the normal keys and the tilde–grave-accent key. Some left-handed Dvorak keyboards have “)(” in strict compliance with the mirror-image concept whereas others have “()” in the customary order. Shown at the right is Dvorak's original ")(" placement of the parentheses, which is the more widely-distributed layout, such as the one that Microsoft supplies with Windows.

Other languages

Although DSK is implemented in many languages other than English, there are still potential issues. Every Dvorak implementation in other languages leaves the Roman characters in the same position as the English DSK. However, other (occidental) language orthographies can clearly have other typing needs for optimization (many are very different from English). Because Dvorak Simplified Keyboard was optimized for the statistical distribution of letters in English text, keyboards for other languages would likely have drastically different distributions of letter frequencies. Hence, non-QWERTY-derived keyboards for such languages would need a keyboard layout that might look quite different from the Dvorak layout for English.

An implementation for Swedish, known as Svorak,[44] places the three extra Swedish vowels (å, ä and ö) on the leftmost three keys of the upper row, which correspond to punctuation symbols on the English Dvorak layout. These punctuation symbols are then juggled with other keys, and the Alt-Gr key is required to access some of them.

Another Swedish version, Svdvorak by Gunnar Parment, keeps the punctuation symbols as they were in the English version; the first extra vowel (å) is placed in the far left of the top row while the other two (ä and ö) are placed at the far left of the bottom row.

The Swedish variant that most closely resembles the American Dvorak layout is Thomas Lundqvist’s sv_dvorak, which places å, ä and ö like Parment’s layout, but keeps the American placement of most special characters.

The Norwegian implementation (known as “Norsk Dvorak”) is similar to Parment’s layout, with “æ” and “ø” replacing “ä” and “ö”.

The Danish layout DanskDvorak[45] is similar to the Norwegian.

A Finnish DAS keyboard layout[46] follows many of Dvorak’s design principles, but the layout is an original design based on the most common letters and letter combinations in the Finnish language. Matti Airas has also made another layout for Finnish.[47] Finnish can also be typed reasonably well with the English Dvorak layout if the letters ä and ö are added. The Finnish ArkkuDvorak keyboard layout[48] adds both on a single key and keeps the American placement for each other character. As with DAS, the SuoRak[49] keyboard is designed by the same principles as the Dvorak keyboard, but with the most common letters of the Finnish language taken into account. Contrary to DAS, it keeps the vowels on the left side of the keyboard and most consonants on the right hand side.

The Turkish F keyboard layout (link) is also an original design with Dvorak's design principles, however it's not clear if it is inspired by Dvorak or not. Turkish F keyboard was standardized in 1955 and the layout has been a requirement for imported typewriters since 1963.

There are some non standard Brazilian Dvorak keyboard layouts currently in development. The simpler design (also called BRDK) is just a Dvorak layout plus some keys from the Brazilian ABNT2 keyboard layout. Another design, however, was specifically designed for writing Brazilian Portuguese, by means of a study that optimized typing statistics, like frequent letters, trigraphs and words.[50]

The most common German Dvorak layout is the German Type II layout. It is available for Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X. There is also the Neo layout[51] and the de ergo layout,[52] both original layouts that also follow many of Dvorak’s design principles. Germans may also use a standard Dvorak layout with ß at the shift+W position (on QWERTY) and the umlaut dots as a dead key accessible via shift+E.

There are also two French[53][54] and three Spanish[55] layouts, and also a proposed Esperanto version.

A Greek version of the Dvorak layout was released on Valentine’s Day 2007. This layout, unlike other Greek Dvorak layouts, preserves the spirit of Dvorak wherein the vowel keys are all placed on the left side of the keyboard. Currently this version is for Mac OS X.[56]

An Italian Mac layout, optimized for this language and with all the accented vowels on the left, is being developed by Paolo Tramannoni.[57] Several PC versions, consisting in the original layout with accented vowels added, are also being developed.

A Romanian version of the Dvorak layout was released in October 2008. It is available for both Windows and Linux.[58]

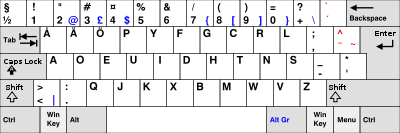

United Kingdom (British) layouts

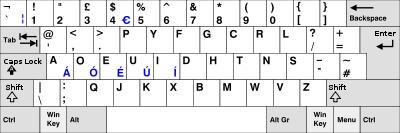

Whether Dvorak or QWERTY, a United Kingdom (British) keyboard differs from the U.S. equivalent in these ways: the " and @ are swapped; the backslash/pipe [\ |] key is in an extra position (to the right of the lower left shift key); there is a taller return/enter key, which places the hash/tilde [# ~] key to its lower left corner (see picture).

The most notable difference between the U.S. and UK Dvorak layouts is the [2 "] key remains on the top row, whereas the U.S. [' "] key moves. This means that the query [/ ?] key retains its classic Dvorak location, top left, albeit shifted.

Interchanging the [/ ?] and [' @] keys more closely matches the U.S. layout, and the use of “@” has increased in the information technology age. These variations, plus keeping the numerals in Dvorak's idealised order, appear in the Classic Dvorak and Dvorak for the Left Hand and Right Hand varieties.

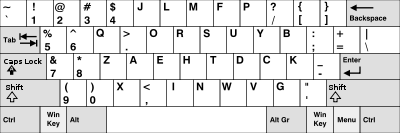

Programmer Dvorak

Programmer Dvorak is a special-purpose variant of the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard created by Roland Kaufmann which is targeted towards programmers. [59] [60] [61] It is available in operating systems that uses the X Keyboard Configuration Database, [62] such as Linux and FreeBSD, or as an add-on for Microsoft Windows and Mac OS X.

While the alphabetic keys are placed as on the standard Dvorak layout, the top row is devoted to symbolic characters and digits are accessed using the shift key, like the French layout. Following August Dvorak's original design, the numerals are not placed in ascending order, but rather with the most used digits on the strongest fingers. [63]

Placement of the symbols is claimed to follow the same principles as for the letters, but using source code instead of prose as underlying statistics.[59] It assumes an alternate finger assignment like the one used on some ergonomic keyboards such as the Microsoft Natural keyboard, where the top row is intended accessed with a slightly rightward-curving motion of the fingers with respect to the home row (see picture) instead of following the left-leaning column.

Notable users

- Piers Anthony, author of the Xanth novels, often wrote in the 1980s author's notes in the books about how his Dvorak use prevented him from converting to a word processor.[64] This was made even more difficult because he uses an alternative Dvorak layout (swapping the hyphen and apostrophe keys – the apostrophe key on his keyboard is where the hyphen key is on a standard U.S. keyboard (and vice-versa)).

- Barbara Blackburn, world typing speed record holder[65]

- Bram Cohen, inventor of BitTorrent[66]

- Terry Goodkind, author of The Sword of Truth[67]

- Holly Lisle, American author[68]

- Matt Mullenweg, co-founder of WordPress[69]

- Nathan Myhrvold, former CTO of Microsoft[70]

- Steve Wozniak, co-founder Apple Computer[71]

- Eliezer Yudkowsky, artificial intelligence researcher and writer: "I switched to Dvorak after a bout of RSI (Repetitive strain injury), and the RSI never came back."[72]

See also

- Dvorak encoding

- Kinesis contoured keyboard

- Maltron keyboard

- Path dependence

- TypeMatrix keyboard

- Velotype

References

- ^ Baker, Nick (11 August 2010). "Why do we all use Qwerty keyboards?". BBC Corporation. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-10925456. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ http://www.microsoft.com/enable/products/altkeyboard.aspx

- ^ a b http://www.dvorak-keyboards.com/Change_qwerty_keyboard_to_Dvorak_in_30_seconds.htm

- ^ http://www.kinesis-ergo.com/advantage.htm

- ^ Cassingham, Randy C. (March 1986). The Dvorak Keyboard. Freelance Communications. p. 20. ISBN 0935309101.

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 18

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 25

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 34

- ^ http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=WSNkAAAAEBAJ&dq=2040248

- ^ [|Liebowitz, S. J.]; Stephen E. Margolis (April 1990). "The Fable of the Keys". Journal of Law & Economics XXXIII. http://www.utdallas.edu/~liebowit/keys1.html. Retrieved 15 Jan 2010.

- ^ "The Fable of the Fable". http://dvorak.mwbrooks.com/dissent.html. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ Jordon Kalilich. "The Dvorak Keyboard and You". http://www.theworldofstuff.com/dvorak/. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ a b c Jared Diamond. "The Curse of QWERTY". http://discovermagazine.com/1997/apr/thecurseofqwerty1099/article_view?b_start:int=0&-C=. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Ober, Scot. "Relative Efficiencies of the Standard and Dvorak Simplified Keyboards". http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/custom/portlets/recordDetails/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=EJ458816&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=EJ458816. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Jonathan Oxer (2004-12-10). "Wrist Pain? Try the Dvorak Keyboard". The Age (Melbourne). http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2004/12/09/1102182415761.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Michael Samson. "Michael Sampson on the Dvorak Keyboard". http://www.productivity501.com/michael-sampson-on-the-dvorak-keyboard/526/. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b Jared Diamond. "The Curse of QWERTY". http://discovermagazine.com/1997/apr/thecurseofqwerty1099/article_view?b_start:int=0&-C=. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ William Hoffer (1985). "The Dvorak keyboard: is it your type?". Nation's Business. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1154/is_v73/ai_3876046/?tag=content;col1. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ a b Strong, E.P. (1956). A Comparative Experiment in Simplified Keyboard Retraining and Standard Keyboard Supplementary Training. Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration

- ^ Touch-Typing: Learning This Lost Art

- ^ Dvorak, August et al. (1936). Typewriting Behavior. American Book Company. Title page.

- ^ Cassingham 1986, pp. 32–35

- ^ a b Robert Parkinson. "The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard: Forty Years of Frustration". http://infohost.nmt.edu/~shipman/ergo/parkinson.html. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ "Barbara Blackburn, the World's Fastest Typist". Archived from the original on 2007-08-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20070805092632/http://rcranger.mysite.syr.edu/famhist/blackburn.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Cassingham 1986, pp. 35–37

- ^ Microsoft.com: Alternative Keyboard Layouts

- ^ "Download details: Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator (MSKLC) Version 1.3.4073". Microsoft.com. 2004-05-20. http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=FB7B3DCD-D4C1-4943-9C74-D8DF57EF19D7&displaylang=en. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ "The Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator". Msdn.microsoft.com. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/goglobal/bb964665.aspx. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ Liebowitz, Stan J.; Stephen E. Margolis (April 1990). "The Fable of the Keys". Journal of Law & Economics 33 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/467198. http://www.utdallas.edu/~liebowit/keys1.html.

- ^ Kissel, Joe. "The Dvorak Keyboard Controversy". http://itotd.com/articles/651/the-dvorak-keyboard-controversy/. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ David, Paul A. (May 1985). "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY". American Economic Review 75: 332–37. and David, Paul A. (1986). "Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: The Necessity of History.". In W. N Parker.. Economic History and the Modern Economist. New York: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631147993.

- ^ Liebowitz, Stan J.; Stephen E. Margolis (April 1990). "The Fable of the Keys". Journal of Law & Economics 33 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/467198. http://www.utdallas.edu/~liebowit/keys1.html. Retrieved 2007-09-19. "We show that David's version of the history of the market's rejection of Dvorak does not report the true history, and we present evidence that the continued use of Qwerty is efficient given the current understanding of keyboard design."

- ^ Brooks, Marcus W. (December 8, 1996). "The Fable of the Fable". http://www.mwbrooks.com/dvorak/dissent.html. Retrieved 2007-09-19. a pro-Dvorak rebuttal of Liebowitz & Margolis

- ^ "US Balks at Teaching Old Typists New Keys". New York Times. 1956-07-02.

- ^ Liebowitz, Stan J. and Margolis, Stephen E. (2001). "The Fable of the Keys". Winners, Losers and Microsoft. Oakland, Calif.: Independent Inst.. p. 30. ISBN 0945999844.

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 52

- ^ a b Cassingham 1986, p. 53

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 49

- ^ a b Cassingham 1986, p. 51

- ^ Robert Ranger. "Barbara Blackburn, the World's Fastest Typist". http://rcranger.mysite.syr.edu/famhist/blackburn.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ "Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator". http://www.microsoft.com/globaldev/tools/msklc.mspx. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ "KbdEdit". http://www.kbdedit.com. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Krzywinski, Martin. "Colemak – Popular Alternative". Carpalx – keyboard layout optimizer. Canada's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre. http://mkweb.bcgsc.ca/carpalx/?colemak. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ Swedish DVORAK keyboard, by Liket and Xtreamist

- ^ Dansk Dvorak – Dvorak er et ergonomisk tastatur layout. Museskade? prøv det ergonomiske Keyboard: Dvorak

- ^ Näppäimistö suomen kielelle

- ^ Airas-keyboard

- ^ My Dvorak keyboard layout

- ^ SuoRak – Dvorak-pohjainen näppäimistö suomen kielelle

- ^ "O que é o teclado brasileiro?". http://www.tecladobrasileiro.com.br/. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ Neo keyboard

- ^ de-ergo – Forschung bei Goebel Consult

- ^ Clavier Dvorak-fr

- ^ Bépo

- ^ Dvorak keyboard layouts

- ^ Greek Dvorak Layout

- ^ Layout italiano Dvorak-Tramannoni

- ^ Tastatura optimizată Popak

- ^ a b Kaufmann, Roland. "Programmer Dvorak Keyboard Layout". http://www.kaufmann.no/roland/dvorak/. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Lee, Xah. "Dvorak, Maltron, Colemak, NEO, Bepo, Turkish-F, Keyboard Layouts Fight!". http://xahlee.blogspot.com/2010/08/dvorak-matron-de-ergo-neo-colemak.html. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ^ Radley, David Stanley. "Programmer Dvorak". http://radderz.me.uk/2008/12/programmer-dvorak/. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ^ "Software/XKeyboardConfig". http://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/XKeyboardConfig. Retrieved 2011-02-05.

- ^ Cassingham 1986, p. 35

- ^ Dvorak inauthor:Piers Anthony

- ^ "Barbara Blackburn, the World's Fastest Typist". Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. http://web.archive.org/web/20080609055056/http://rcranger.mysite.syr.edu/famhist/blackburn.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ^ Cohen, Bram (March 7, 2006). "Keyboard Switching". http://bramcohen.livejournal.com/30675.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ "Terry Goodkind – Interviews and Past Chats". Archived from the original on 2007-06-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20070605135708/http://www.prophets-inc.com/the_author/pi2.html. Retrieved 2007-08-20. "I type on a dvorak keyboard layout..."

- ^ Holly Lisle. "Dvorak & Me – Three Months Later". http://hollylisle.com/index.php/Writing-Life/dvorak-a-me-three-months-later.html. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Mullenweg, Matt (August 31, 2003). "On the Dvorak Keyboard Layout". http://ma.tt/2003/08/on-the-dvorak-keyboard-layout/. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ "Dvorak Typists – Matt Mullenweg". Ma.tt. 2007-05-25. http://ma.tt/2007/05/dvorak-typists/. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ "Slashdot Comments | Dvorak Layout Claimed Not Superior To QWERTY". Hardware.slashdot.org. 2009-01-18. http://hardware.slashdot.org/comments.pl?sid=1096247&cid=26511091. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ http://lesswrong.com/lw/453/procedural_knowledge_gaps/3igl

External links

- DvZine.org – A print and webcomic zine advocating the Dvorak Keyboard and teaching its history.

- A Basic Course in Dvorak – by Dan Wood

- A Basic Course in Dvorak with javascript – by Dan Wood and Marcus Hayward

- LinkedIn group of Dvorak users

- Dvorak vs Qwerty – Online tool that compares the efficiency of the Dvorak layout and the standard Qwerty layout.

- [1] – Comparison of common optimal keyboard layouts, including Dvorak.

QWERTY based Alternative layouts Non-Roman Arabic · Dzongkha (Tibetan) · Hebrew · InScript (Indian languages Hindi, Telugu etc) · Urdu · Russian (pre-reform) · Russian (post-reform)For mobile devices Chorded keyboards Historical Categories:- Computer keyboards

- Ergonomics

- Keyboard layouts

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.