- Jellyfish

-

For other uses, see Jellyfish (disambiguation).

Jellyfish

Temporal range: 505–0 Ma Cambrian – Recent

Atlantic sea nettle

Chrysaora quinquecirrhaScientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Cnidaria Subphylum: Medusozoa

Petersen, 1979Classes Jellyfish (also known as jellies or sea jellies or a stage of the life cycle of Medusozoa) are free-swimming members of the phylum Cnidaria. Medusa is another word for jellyfish, and refers to any free-swimming jellyfish stages in the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish have several different morphologies that represent several different cnidarian classes including the Scyphozoa (over 200 species), Staurozoa (about 50 species), Cubozoa (about 20 species), and Hydrozoa (about 1000–1500 species that make jellyfish and many more that do not).[1][2]

Jellyfish are found in every ocean, from the surface to the deep sea. Some hydrozoan jellyfish, or hydromedusae, are also found in fresh water; freshwater jellyfish are less than an inch (25 mm) in diameter, are colorless and do not sting. Large, often colorful, jellyfish are common in coastal zones worldwide. Scientists have evidence of jellyfish roaming the seas for about 500 million years.[3]

In its broadest sense, the term jellyfish also generally refers to members of the phylum Ctenophora. Although not closely related to cnidarian jellyfish, ctenophores are also free-swimming planktonic carnivores, are generally transparent or translucent, and exist in shallow to deep portions of all the world's oceans.

Alternative names for groups of jellyfish are scyphomedusae, stauromedusae, cubomedusae, and hydromedusae. These may relate to an entire order or class.[4]

Contents

Terminology

The word jellyfish (which has been in common usage for more than a century)[5] is used to denote several different kinds of cnidarians, all of which have a basic body structure that resembles an umbrella, including scyphozoans, staurozoans (stalked jellyfish), hydrozoans, and cubozoans (box jellyfish). Some textbooks and websites refer to scyphozoans as "true jellyfish".[6][7]

As jellyfish are not even vertebrates, let alone true fish, the usual word jellyfish is considered by some to be a misnomer, and American public aquariums have popularized use of the terms jellies or sea jellies instead.[8]

In its broadest usage, some scientists occasionally include members of the phylum Ctenophora (comb jellies) when they are referring to jellyfish.[9] Other scientists prefer to use the more all-encompassing term "gelatinous zooplankton", when referring to these, together with other soft-bodied animals in the water column.[10]

A group of jellyfish is sometimes called a bloom or a swarm.[11] "Bloom" is usually used for a large group of jellyfish that gather in a small area, but may also have a time component, referring to seasonal increases, or numbers beyond what was expected.[12] Another collective name for a group of jellyfish is a smack.[13]

Jellyfish are "bloomy" by nature of their life cycles, being produced by their benthic polyps usually in the spring when sunshine and plankton increase, so they appear rather suddenly and often in large numbers, even when an ecosystem is in balance.[14] Using "swarm" usually implies some kind of active ability to stay together, which a few species like Aurelia, the moon jelly, demonstrate.[15]

Most jellyfish have a second part of their life cycle, which is called the polyp phase. When single polyps, arising from a single fertilized egg, develop into a multiple-polyp cluster, connected to each other by strands of tissue called stolons, they are said to be "colonial". A few polyps never proliferate and are referred to as "solitary" species.[16]

Anatomy

Most Jellyfish do not have specialized digestive, osmoregulatory, central nervous, respiratory, or circulatory systems. They digest using the gastrodermal lining of the gastrovascular cavity, where nutrients are absorbed. They do not need a respiratory system since their skin is thin enough that the body is oxygenated by diffusion. They have limited control over movement, but can use their hydrostatic skeleton to accomplish movement through contraction-pulsations of the bell-like body; some species actively swim most of the time, while others are passive much of the time.[citation needed] Jellyfish are composed of more than 90% water; most of their umbrella mass is a gelatinous material — the jelly — called mesoglea which is surrounded by two layers of epithelial cells which form the umbrella (top surface) and subumbrella (bottom surface) of the bell, or body.

Most jellyfish do not have a brain or central nervous system, but rather has a loose network of nerves, located in the epidermis, which is called a "nerve net". A jellyfish detects various stimuli including the touch of other animals via this nerve net, which then transmits impulses both throughout the nerve net and around a circular nerve ring, through the rhopalial lappet, located at the rim of the jellyfish body, to other nerve cells. Some jellyfish also have ocelli: light-sensitive organs that do not form images but which can detect light, and are used to determine up from down, responding to sunlight shining on the water's surface. These are generally pigment spot ocelli, which have some cells (not all) pigmented.

Certain species of jellyfish, such as the Box jellyfish, have been revealed to be more advanced than their primitive counterparts. The Box jellyfish has 24 eyes, two of which are capable of seeing color, and four parallel brains that act in competition, supposedly making it one of the only creatures to have a 360 degree view of its environment.[17] It is suggested that the two eyes that contain cornea and retina are attached to a central nervous system which enables the four brains to process images. It is unknown how this works, as the creature has an as yet unseen type of central nervous system.[18]

It has also been found that certain species of the Box Jellyfish sleep on the sea bed in shallow water.[19]

Jellyfish blooms

Aurelia sp., occurs in large quantities in most of the world's coastal waters. Members of this genus are nearly identical to each other.

Aurelia sp., occurs in large quantities in most of the world's coastal waters. Members of this genus are nearly identical to each other.

The presence of ocean blooms is usually seasonal, responding to prey availability and increasing with temperature and sunshine. Ocean currents tend to congregate jellyfish into large swarms or "blooms", consisting of hundreds or thousands of individuals. In addition to sometimes being concentrated by ocean currents, blooms can result from unusually high populations in some years. Bloom formation is a complex process that depends on ocean currents, nutrients, temperature, predation, and oxygen concentrations. Jellyfish are better able to survive in oxygen-poor water than competitors, and thus can thrive on plankton without competition. Jellyfish may also benefit from saltier waters, as saltier waters contain more iodine, which is necessary for polyps to turn into jellyfish. Rising sea temperatures caused by climate change may also contribute to jellyfish blooms, because many species of jellyfish are better able to survive in warmer waters.[20] Jellyfish are likely to stay in blooms that are quite large and can reach up to 100,000 in each.

There is very little data about changes in global jellyfish populations over time, besides "impressions" in the public memory. Scientists have little quantitative data of historic or current jellyfish populations.[14] Recent speculation about increases in jellyfish populations are based on no "before" data.

The global increase in jellyfish bloom frequency may stem from human impact. In some locations jellyfish may be filling ecological niches formerly occupied by now overfished creatures, but this hypothesis lacks supporting data.[14] Jellyfish researcher Marsh Youngbluth further clarifies that "jellyfish feed on the same kinds of prey as adult and young fish, so if fish are removed from the equation, jellyfish are likely to move in."[21]

Some jellyfish populations that have shown clear increases in the past few decades are "invasive" species, newly arrived from other habitats: examples include the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, the Baltic Sea, the eastern Mediterranean coasts of Egypt and Israel[22], and the American coast of the Gulf of Mexico.[citation needed] Populations of invasive species can expand rapidly because there are often no natural predators in the new habitat to check their growth. Such blooms would not necessarily reflect overfishing or other environmental problems.

Increased nutrients, ascribed to agricultural runoff, have also been cited as an antecedent to the proliferation of jellyfish. Monty Graham, of the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama, says that "ecosystems in which there are high levels of nutrients ... provide nourishment for the small organisms on which jellyfish feed. In waters where there is eutrophication, low oxygen levels often result, favoring jellyfish as they thrive in less oxygen-rich water than fish can tolerate. The fact that jellyfish are increasing is a symptom of something happening in the ecosystem."[21]

Life cycle

See also: Biological life cycle and Developmental biologyJellyfish are usually either male or female (occasionally hermaphroditic specimens are found). In most cases, both release sperm and eggs into the surrounding water, where the (unprotected) eggs are fertilized and mature into new organisms. In a few species, the sperm swim into the female's mouth fertilizing the eggs within the female's body where they remain for the early stages of development. In moon jellies, the eggs lodge in pits on the oral arms, which form a temporary brood chamber for the developing planula larvae.

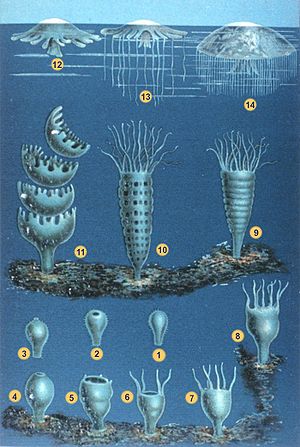

Most jellyfish undergo two distinct life history stages (body forms) during their life cycle. The first is the polypoid stage. After fertilization and initial growth, a larval form, called the planula, develops. The planula is a small larva covered with cilia. It settles onto a firm surface and develops into a polyp. The polyp is generally a small stalk with a mouth surrounded by upward-facing tentacles like miniatures of the closely related anthozoan polyps (sea anemones and corals), also of the phylum Cnidaria. This polyp may be sessile, living on the bottom or on similar substrata such as floats or boat-bottoms, or it may be free-floating or attached to tiny bits of free-living plankton[23] or rarely, fish[24] or other invertebrates. Polyps may be solitary or colonial, and some bud asexually by various means, making more polyps. Most are very small, measured in millimeters.

After a growth interval, the polyp begins reproducing asexually by budding and, in the Scyphozoa, is called a segmenting polyp, or a scyphistoma. New scyphistomae may be produced by budding or new, immature jellies called ephyrae may be formed. A few jellyfish species can produce new medusae by budding directly from the medusan stage. Budding sites vary by species; from the tentacle bulbs, the manubrium (above the mouth), or the gonads of hydromedusae. A few of species of hydromedusae reproduce by fission (splitting in half).[23]

In the second stage, the tiny polyps asexually produce jellyfish, each of which is also known as a medusa. Tiny jellyfish (usually only a millimeter or two across) swim away from the polyp and then grow and feed in the plankton.[citation needed] Medusae have a radially symmetric, umbrella-shaped body called a bell, which is usually supplied with marginal tentacles - fringe-like protrusions from the bell's border that capture prey. A few species of jellyfish do not have the polyp portion of the life cycle, but go from jellyfish to the next generation of jellyfish through direct development of fertilized eggs.

Other species of jellyfish are among the most common and important jellyfish predators, some of which specialize in jellies. Other predators include tuna, shark, swordfish, sea turtles and at least one species of Pacific salmon. Sea birds sometimes pick symbiotic crustaceans from the jellyfish bells near the sea's surface, inevitably feeding also on the jellyfish hosts of these amphipods or young crabs and shrimp.

Jellyfish lifespans typically range from a few hours (in the case of some very small hydromedusae) to several months. Life span and maximum size varies by species. One unusual species is reported to live as long as 30 years. Another species, Turritopsis dohrnii as T. nutricula, may be effectively immortal because of its ability to transform between medusa and polyp, thereby escaping death.[25] Most large coastal jellyfish live 2 to 6 months, during which they grow from a millimeter or two to many centimeters in diameter. They feed continuously and grow to adult size fairly rapidly. After reaching adult size, jellyfish spawn daily if there is enough food. In most species, spawning is controlled by light, so the entire population spawns at about the same time of day, often at either dusk or dawn.[26]

Relationship to humans

Culinary

Cannonball jellyfish, Stomolophus meleagris, are harvested for culinary purposes.

Cannonball jellyfish, Stomolophus meleagris, are harvested for culinary purposes.

Only scyphozoan jellyfish belonging to the order Rhizostomeae are harvested for food; about 12 of the approximately 85 species are harvested and sold on international markets. Most of the harvest takes place in southeast Asia.[27] Rhizostomes, especially Rhopilema esculentum in China (海蜇 hǎizhē, "sea stings") and Stomolophus meleagris (cannonball jellyfish) in the United States, are favored because of their larger and more rigid bodies and because their toxins are harmless to humans.[28]

Traditional processing methods, carried out by a Jellyfish Master, involve a 20 to 40 day multi-phase procedure in which after removing the gonads and mucous membranes, the umbrella and oral arms are treated with a mixture of table salt and alum, and compressed.[28] Processing reduces liquefaction, off-odors and the growth of spoilage organisms, and makes the jellyfish drier and more acidic, producing a "crunchy and crispy texture."[28] Jellyfish prepared this way retain 7-10% of their original weight, and the processed product contains approximately 94% water and 6% protein.[28] Freshly processed jellyfish has a white, creamy color and turns yellow or brown during prolonged storage.

In China, processed jellyfish are desalted by soaking in water overnight and eaten cooked or raw. The dish is often served shredded with a dressing of oil, soy sauce, vinegar and sugar, or as a salad with vegetables.[28] In Japan, cured jellyfish are rinsed, cut into strips and served with vinegar as an appetizer.[28][29] Desalted, ready-to-eat products are also available.[28]

Fisheries have begun harvesting the American cannonball jellyfish, Stomolophus meleagris, along the southern Atlantic coast of the United States and in the Gulf of Mexico for export to Asia.[28]

In biotechnology

The hydromedusa Aequorea victoria.

The hydromedusa Aequorea victoria.

In 1961, Osamu Shimomura of Princeton University extracted green fluorescent protein (GFP) and another bioluminescent protein, called aequorin, from the large and abundant hydromedusa Aequorea victoria, while studying photoproteins that cause bioluminescence by this species of jellyfish. Three decades later, Douglas Prasher, a post-doctoral scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, sequenced and cloned the gene for GFP. Martin Chalfie of Columbia University soon figured out how to use GFP as a fluorescent marker of genes inserted into other cells or organisms. Roger Tsien of University of California, San Diego, later chemically manipulated GFP in order to get other colors of fluorescence to use as markers. In 2008, Shimomura, Chalfie, and Tsien won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work with GFP.

Man-made GFP is now commonly used as a fluorescent tag to show which cells or tissues express specific genes. The genetic engineering technique fuses the gene of interest to the GFP gene. The fused DNA is then put into a cell, to generate either a cell line or (via IVF techniques) an entire animal bearing the gene. In the cell or animal, the artificial gene turns on in the same tissues and the same time as the normal gene. But instead of making the normal protein, the gene makes GFP. One can then find out what tissues express that protein—or at what stage of development—by shining light on the animal or cell and observing fluorescence. The fluorescence shows where the gene is expressed.[30]

Jellyfish are also harvested for their collagen, which can be used for a variety of applications including the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

In captivity

A group of Pacific sea nettle jellyfish, Chrysaora fuscescens, in an aquarium exhibit.

A group of Pacific sea nettle jellyfish, Chrysaora fuscescens, in an aquarium exhibit.

Jellyfish are displayed in aquariums in many countries. Often the tank's background is blue and the animals are illuminated by side light, increasing the contrast between the animal and the background. In natural conditions, many jellies are so transparent that they are nearly invisible.

Jellyfish are not adapted to closed spaces. They depend on currents to transport them from place to place. Professional exhibits feature precise water flows, typically in circular tanks to prevent specimens from becoming trapped in corners. The Monterey Bay Aquarium uses a modified version of the kreisel (German for "spinning top") for this purpose. Jellyfish are becoming a popular trend in home aquaria. It is now possible to buy jellyfish aquaria and live jellyfish online.[31][32][33] It is also possible to assemble a jellyfish aquarium for personal use.[34]

Toxicity

All jellyfish sting their prey using nematocysts, also called cnidocysts, stinging structures located in specialized cells called cnidocytes, which are characteristic of all Cnidaria. Contact with a jellyfish tentacle can trigger millions of nematocysts to pierce the skin and inject venom,[35] yet only some species have a sting that will cause an adverse reaction in humans. When a nematocyst is triggered by contact by predator or prey, pressure builds up rapidly inside it up to 2,000 lbs/sq. inch until it bursts open. A lance inside the nematocyst pierces the victim's skin, and poison flows through into the victim.[36] Touching or being touched by a jellyfish can be very uncomfortable, sometimes requiring medical assistance; sting effects range from no effect to extreme pain or even death. Because of the wide variation in response to jellyfish stings, it is wisest not to contact any jellyfish with bare skin. Even beached and dying jellyfish can still sting when touched.

Scyphozoan jellyfish stings range from a twinge to tingling to savage agony.[37] Most jellyfish stings are not deadly, but stings of some species of the class Cubozoa and the Box jellyfish, such as the famous and especially toxic Irukandji jellyfish, can be deadly. Stings may cause anaphylaxis, which can be fatal. Medical care may include administration of an antivenom.

In 2010 at a New Hampshire beach, pieces of a single dead lion's mane jellyfish stung between 125 and 150 people.[38][39] Jellyfish kill 20 to 40 people a year in the Philippines alone.[37] In 2006 the Spanish Red Cross treated 19,000 stung swimmers along the Costa Brava.[37]

Treatment

The three goals of first aid for uncomplicated jellyfish stings are to prevent injury to rescuers, deactivate the nematocysts, and remove tentacles attached to the patient. Rescuers need to wear barrier clothing, such as pantyhose, wet suits or full-body sting-proof suits. Deactivating the nematocysts (stinging cells) prevents further injection of venom.

Vinegar (3 to 10% aqueous acetic acid) is a common remedy to help with box jellyfish stings,[40][41] but not the stings of the Portuguese Man o' War (which is not a true jellyfish, but a colony).[40] For stings on or around the eyes, a towel dampened with vinegar is used to dab around the eyes, with care taken to avoid the eyeballs. Salt water is also used if vinegar is unavailable.[40][42] Fresh water is not used if the sting occurs in salt water, as changes in tonicity[43] can release additional venom. Rubbing wounds, or using alcohol, spirits, ammonia, or urine may have strongly negative effects as these can also encourage the release of venom.[44]

Clearing the area of jelly, tentacles, and wetness further reduces nematocyst firing.[44] Scraping the affected skin with a knife edge, safety razor, or credit card can remove remaining nematocysts.[45]

Beyond initial first aid, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can control skin irritation (pruritus).[45] For removal of venom in the skin, a paste of baking soda and water can be applied with a cloth covering on the sting.[citation needed] In some cases it is necessary to reapply paste every 15–20 minutes. Ice or fresh water should not be applied to the sting, as this may help the nematocysts to continue releasing their toxin.[46][47]

Overpopulation

Evidence in recent years suggest that the population of jellyfish has swelled as a result of overfishing which reduces the number of predatory organisms that feed on them. This has allowed jellyfish to proliferate to the extent that they adversely affect humanity by interfering with public systems and harming swimmers.[37] Jellyfish blooms cause problems for mankind. The most obvious are stings to humans (sometimes deadly), and causing coastal tourism to decline. Other problems are destroying fish nets, poisoning or crushing captured fish, and consuming fish eggs and young fish.[48]

By clogging cooling equipment en masse, jellyfish have disabled power plants in several countries, including a cascading blackout in the Philippines in 1999[37] as well as in the Diablo Canyon Power Plant in California in 2010.[49] Clogging also causes many problems including stoppage of nuclear power plants and desalination plants, as well as clogging engines of ships[48] and making pull in of fishing nets hazardous.[50]

In media

New discoveries about jellyfish and their prevalence are reflected on television in programs such as in "Jellyfish Invasion," which is an episode of the National Geographic Channel documentary series Explorer,[51][52][53] which includes research conducted by scientists in Australia, Hawaii and Japan.

The Disney Pixar animated film Finding Nemo shows the near fatal effects of swimming through a jellyfish bloom. The opening sequence of the animated film Ponyo depicts a massive jellyfish bloom off the coast of Japan.

The Japanese science fiction film Dogora features jellyfish-like space creatures. The Japanese anime Kuragehime features a main character who is obsessed with jellyfish, and has jellyfish related plotlines.

In the Will Smith movie Seven Pounds, Will Smith's character had a pet jellyfish which was an important piece to the end of the movie.

On an episode of Survivor Palau, the team winning the reward challenge got to swim in Jellyfish Lake, a lake full of golden jellyfish, which are harmless to Humans.

On the "A Star is Born Again" episode of The Simpsons, the fictional town of Springfield holds a Jellyfish Festival, portrayed as a magical evening celebrating the waters and beach being overrun with jellyfish.

Taxonomy

Taxonomic classification systematics within the Cnidaria, as with all organisms, are always in flux. Many scientists who work on relationships between these groups are reluctant to assign ranks, although there is general agreement on the different groups, regardless of their absolute rank. Presented here is one scheme, which includes all groups that produce medusae (jellyfish), derived from several expert sources:

Jellyfish taxonomy (phylum Cnidaria: subphylum Medusozoa) Class Subclass Order Suborder Families Hydrozoa [54][55] Hydroidolina Anthomedusae Filifera see [54] Capitata see [54] Leptomedusae Conica see [54] Proboscoida see [54] Siphonophorae Physonectae Agalmatidae, Apolemiidae, Erennidae, Forskaliidae, Physophoridae, Pyrostephidae, Rhodaliidae Calycophorae Abylidae, Clausophyidae, Diphyidae, Hippopodiidae, Prayidae, Sphaeronectidae Cystonectae Physaliidae, Rhizophysidaev Trachylina Limnomedusae Olindiidae, Monobrachiidae, Microhydrulidae, Armorhydridae Trachymedusae Geryoniidae, Halicreatidae, Petasidae, Ptychogastriidae, Rhopalonematidae Narcomedusae Cuninidae, Solmarisidae, Aeginidae, Tetraplatiidae Actinulidae Halammohydridae, Otohydridae Staurozoa[56] Eleutherocarpida Lucernariidae, Kishinouyeidae, Lipkeidae, Kyopodiidae Cleistocarpida Depastridae, Thaumatoscyphidae, Craterolophinae Cubozoa [57] Carybdeidae, Alatinidae, Tamoyidae, Chirodropidae, Chiropsalmidae Scyphozoa [57] Coronatae Atollidae, Atorellidae, Linuchidae, Nausithoidae, Paraphyllinidae, Periphyllidae Semaeostomeae Cyaneidae, Pelagiidae, Ulmaridae Rhizostomeae Cassiopeidae, Catostylidae, Cepheidae, Lychnorhizidae, Lobonematidae, Mastigiidae, Rhizostomatidae, Stomolophidae Largest jellyfish

The lion's mane jellyfish are arguably the longest animal in the world

The lion's mane jellyfish are arguably the longest animal in the world

The lion's mane jellyfish, Cyanea capillata, have long been cited as the largest known jellyfish, and are arguably the longest animal in the world, with fine, thread-like tentacles up to 36.5 m (120 feet) long (though most are nowhere near that large).[58][59][60] They have a painful, but rarely fatal, sting.

The increasingly common giant Nomura's jellyfish, Nemopilema nomurai, found some, but not all years in the waters of Japan, Korea and China in summer and autumn is probably a much better candidate for "largest jellyfish", since the largest Nomura's jellyfish in late autumn can reach 200 cm (79 inches) in bell (body) diameter and about 200 kg (440 lbs) in weight, with average specimens frequently reaching 90 cm (35 inches) in bell diameter and about 150 kg (330 lbs) in weight.[61][62] The large bell mass of the giant Nomura's jellyfish[63] can dwarf a diver and is nearly always much greater than the up-to-100 cm bell diameter Lion's Mane.[64]

The rarely-encountered deep-sea jellyfish Stygiomedusa gigantea is another solid candidate for "largest jellyfish", with its 100 cm wide, and thick, massive bell and four thick, "paddle-like" oral arms extending up to 600 cm in length,[65] very different than the typical fine, threadlike tentacles that rim the umbrella of more-typical-looking jellyfish, including the Lion's Mane.

Gallery

-

Upside-down jellyfish, in Jellyfish Lake, harbor algae in their tentacles which they turn up to the sun to promote photosynthesis.

See also

- Jellyfish dermatitis

- Ocean sunfish a significant jellyfish predator

- List of prehistoric medusozoans

References

- ^ Marques, A.C.; A. G. Collins (2004). "Cladistic analysis of Medusozoa and cnidarian evolution". Invertebrate Biology 123: 23–42. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2004.tb00139.x.

- ^ Kramp, P.L. (1961). "Synopsis of the Medusae of the World". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 40: 1–469.

- ^ Public Library of Science. "Fossil Record Reveals Elusive Jellyfish More Than 500 Million Years Old." ScienceDaily, 2 Nov. 2007. Web. 16 Apr. 2011.[1]

- ^ "There's no such thing as a jellyfish". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3HzFiQFFQYw&feature=channel_video_title. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ Kelman, Janet Harvey; Rev. Theodore Wood (1910). The Sea-Shore, Shown to the Children. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack. p. 146.

- ^ Klappenbach, Laura. "Ten Facts about Jellyfish". http://animals.about.com/od/cnidarians/a/tenfactsjellyfi.htm. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ "What are some determining characteristics of jellyfish in the class, Scyphozoa?". http://qanda.encyclopedia.com/question/some-determining-characteristics-jellyfish-class-scyphozoa-97854.html. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ Flower Hat Jelly[dead link], New York Aquarium, retrieved Aug 2009.

- ^ Kaplan, Eugene H.; Kaplan, Susan L.; Peterson, Roger Tory (August 1999). A Field Guide to Coral Reefs: Caribbean and Florida. Boston : Houghton Mifflin. p. 55. ISBN 0-6180-0211-1. http://books.google.com/?id=OLYPWMoBkccC&pg. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ^ Haddock, S.H.D., and Case, J.F. (April 1999). "Bioluminescence spectra of shallow and deep-sea gelatinous zooplankton: ctenophores, medusae and siphonophores". Marine Biology 133: 571. doi:10.1007/s002270050497. http://www.lifesci.ucsb.edu/~haddock/abstracts/haddock_spectra.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "Jellyfish Gone Wild" (Text of Flash). National Science Foundation. 3 March 2009. http://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/jellyfish/textonly/intro.jsp. Retrieved 17 November 2009. "In recent years, massive blooms of stinging jellyfish and jellyfish-like creatures have overrun some of the world’s most important fisheries and tourist destinations.... Jellyfish swarms have also damaged fisheries, fish farms, seabed mining operations, desalination plants and large ships."

- ^ "Jellyfish Take Over an Over-Fished Area". 21 July 2006. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5573968. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "Smack of Jellyfish". Smack of Jellyfish. http://smackofjellyfish.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ a b c Mills, C.E. (2001). "Jellyfish blooms: are populations increasing globally in response to changing ocean conditions?". Hydrobiologia 451: 55–68. doi:10.1023/A:1011888006302. http://faculty.washington.edu/cemills/jellyblooms2001.pdf.

- ^ Hamner, W. M.; P. P. Hamner, S. W. Strand (1994). "Sun-compass migration by Aurelia aurita (Scyphozoa): population retention and reproduction in Saanich Inlet, British Columbia.". Marine Biology 119: 347–356.. doi:10.1007/BF00347531.

- ^ Schuchert, Peter. "The Hydrozoa". http://www.ville-ge.ch/mhng/hydrozoa/hydrozoa-directory.htm. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18624995.700-multieyed-jellyfish-helps-with-darwins-puzzle.html

- ^ www.mhest.com/spotlight/underthesea/.../EST_Box_jellyfish_YB.pdf

- ^ homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/class/Psy355D/jellyfish.pdf

- ^ Shubin, Kristie (10 December 2008). "Anthropogenic Factors Associated with Jellyfish Blooms - Final Draft II". http://jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu/fieldcourses08/PapersMarineEcologyArticles/AnthropogenicFactorsAssocA.html. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ a b The Washington Post, republished in the European Cetacean Bycatch Campaign, Jellyfish “blooms” could be sign of ailing seas, May 6, 2002. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ World's most invasive jellyfish spreading along Israel coast Haaretz article from June 15'th 2009

- ^ a b Mills, C. E. (1987). "In situ and shipboard studies of living hydromedusae and hydroids: preliminary observations of life-cycle adaptations to the open ocean". Modern Trends in the Systematics, Ecology, and Evolution of Hydroids and Hydromedusae (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

- ^ Fewkes, J. Walter (1887). "A hydroid parasitic on a fish". Nature 36 (939): 604–605. doi:10.1038/036604b0.

- ^ Piraino, S.; Boero, F.; Aeschbach, B.; Schmid, V. (1996). "Reversing the life cycle: medusae transforming into polyps and cell transdifferentiation in Turritopsis nutricula (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa)". Biological Bulletin 190 (3): 302–312. doi:10.2307/1543022. http://jstor.org/stable/1543022.

- ^ Mills, Claudia (1983). "Vertical migration and diel activity patterns of hydromedusae: studies in a large tank.". Journal of Plankton Research 5: 619–635. doi:10.1093/plankt/5.5.619.

- ^ Omori M., Nakano E. (2001). "Jellyfish fisheries in southeast Asia". Hydrobiologia 451: 19–26. doi:10.1023/A:1011879821323.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Y-H. Peggy Hsieh, Fui-Ming Leong, and Jack Rudloe (2004). "Jellyfish as food". Hydrobiologia 451 (1-3): 11–17. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 6102347. http://www.springerlink.com/content/x7204250k4174gwt/.

- ^ Firth, F.E. (1969). The Encyclopedia of Marine Resources. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.. New York. ISBN 0442223994.

- ^ Pieribone, V. and D.F. Gruber (2006). Aglow in the Dark: The Revolutionary Science of Biofluorescence. Harvard University Press. pp. 288p. http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog/PIEAGL.html.

- ^ Richtel, Matt (14 March 2009). "How to Avoid Liquefying Your Jellyfish". The New York Times. http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/03/14/how-to-avoid-liquefying-your-jellyfish/. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Garage brands". Airtran Magazine. http://www.airtranmagazine.com/features/2009/08/garage-brands. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ "Jellyfish Art". http://www.jellyfishart.com/.

- ^ "How to Start a Jellyfish Tank". wikiHow. 2010-10-07. http://www.wikihow.com/Start-a-Jellyfish-Tank. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Purves WK, Sadava D, Orians GH, Heller HC. 1998. Life.The Science of Biology. Part 4: The Evolution of Diversity. Chapter 31

- ^ KB Results

- ^ a b c d e Tucker, Abigail (July 2010). "The New King of the Sea". Smithsonian

- ^ Ouch! Jellyfish stings 150 on N.H. beach, Boston Globe, July 21, 2010

- ^ Death Does Not Deter Jellyfish Sting, The New York Times, July 22, 2010

- ^ a b c Fenner P, Williamson J, Burnett J, Rifkin J (1993). "First aid treatment of jellyfish stings in Australia. Response to a newly differentiated species". Med J Aust 158 (7): 498–501. PMID 8469205.

- ^ Currie B, Ho S, Alderslade P (1993). "Box-jellyfish, Coca-Cola and old wine". Med J Aust 158 (12): 868. PMID 8100984.

- ^ Yoshimoto C; Leong, Fui-Ming; Rudloe, Jack (2006). "Jellyfish species distinction has treatment implications". Am Fam Physician 73 (3): 391. PMID 16477882.

- ^ Paul Auerbach, M.D. (2008-01-19). "Meat Tenderizer for a Jellyfish Sting". Healthline.com. http://www.healthline.com/blogs/outdoor_health/2008/01/meat-tenderizer-for-jellyfish-sting.html. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ a b Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J (1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". Med J Aust 1 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 6102347.

- ^ a b Perkins R, Morgan S (2004). "Poisoning, envenomation, and trauma from marine creatures". Am Fam Physician 69 (4): 885–90. PMID 14989575.

- ^ "Jellyfish Stings Causes, Symptoms, Treatment - Jellyfish Stings Treatment on eMedicineHealth". Emedicinehealth.com. 2011-04-07. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/jellyfish_stings/page4_em.htm. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ "Jellyfish sting treatment?". Healthcareask.com. http://www.healthcareask.com/first-aid/first-aid-5-7563.html. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ a b "Jellyfish Gone Wild — Text-only". Nsf.gov. http://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/jellyfish/textonly/swarms.jsp. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ "Current Event Notification Report". NRC. October 22, 2008. http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/event-status/event/2008/20081022en.html#en44588. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (2 November 2009). "Japanese fishing trawler sunk by giant jellyfish". London: Telegraph.co.uk. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/6483758/Japanese-fishing-trawler-sunk-by-giant-jellyfish.html. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Jellyfish Invasion, National Geographic, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ Jellyfish Invasion, YouTube, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ Killer jellyfish population explosion warning, The Daily Telegraph, 11 February 2008, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Schuchert, Peter. "The Hydrozoa Directory". http://www.ville-ge.ch/mhng/hydrozoa/hydrozoa-directory.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ Mills, C.E., D.R. Calder, A.C. Marques, A.E. Migotto, S.H.D. Haddock, C.W. Dunn and P.R. Pugh, 2007. Combined species list of Hydroids, Hydromedusae, and Siphonophores. pp. 151-168. In Light and Smith's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. Fourth Edition (J.T. Carlton, editor). University of California Press, Berkeley.

- ^ Mills, Claudia E. "Stauromedusae: List of all valid species names". http://faculty.washington.edu/cemills/Staurolist.html. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ a b Dawson, Michael N. "The Scyphozoan". http://thescyphozoan.ucmerced.edu/. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ "Rare sighting of a lion’s mane jellyfish in Tramore Bay". Waterford Today. http://www.waterford-today.ie/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=933&Itemid=10177&ed=68. Retrieved 2010-10-18.[dead link]

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Lion’s Mane Jellyfish - Reference Library". redOrbit. http://www.redorbit.com/education/reference_library/cnidaria/lions_mane_jellyfish/4326/index.html. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Omori, Makoto; Kitamura, Minoru (2004). "Taxonomic review of three Japanese species of edible jellyfish (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae)" (PDF). Plankton Biology and Ecology 51 (1): 36–51. http://www.plankton.jp/PBE/issue/vol51_1/vol51_1_036.pdf.

- ^ Uye, Shin-Ichi (2008). "Blooms of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai: a threat to the fisheries sustainability of the East Asian Marginal Seas". Plankton & Benthos Research 3 (Supplement): 125–131.

- ^ "Giant Echizen jellyfish off Japan coast". BBC. 2009-11-30. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8385953.stm.

- ^ Kramp, P.L. (1961). "Synopsis of the medusae of the world". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 40: 1–469.

- ^ Bourton, Jody (23 April 2010). "Giant deep sea jellyfish filmed in Gulf of Mexico". BBC Earth News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8638000/8638527.stm.

External links

- Explore Jellyfish - Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Jellyfish and Other Gelatinous Zooplankton

- Jellyfish Facts - Information on Jellyfish and Jellyfish Safety

- Cotylorhiza tuberculata

- "There's no such thing as a jellyfish" from The MBARI YouTube channel

Photos:

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.