- Négritude

-

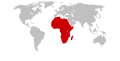

Négritude is a literary and ideological movement, developed by francophone black intellectuals, writers, and politicians in France in the 1930s by a group that included the future Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor, Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, and the Guianan Léon Damas.

The Négritude writers found solidarity in a common black identity as a rejection of perceived French colonial racism. They believed that the shared black heritage of members of the African diaspora was the best tool in fighting against French political and intellectual hegemony and domination. They formed a realistic literary style and formulated their Marxist ideas as part of this movement.

Contents

Influences

In 1885, Haitian anthropologist Anténor Firmin published an early work of négritude De l'Égalité des Races Humaines (English: On the Equality of Human Races), which was published as a rebuttal to French writer Count Arthur de Gobineau's work Essai sur l'inegalite des Races Humaines (English: Essay on the Inequality of Human Races). Firmin had an impact on Jean Price-Mars, the founder of Haitian ethnology and on 20th century American anthropologist Melville Herskovits.[1]

The Harlem Renaissance, centred on Harlem in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s, had a significant influence on the Negritude movement.[2] The movement's writers including Langston Hughes, and slightly later figures such as Richard Wright, addressed the themes of "noireism" and racism. Further inspiration came from Haiti, where there had similarly been a flourishing of black culture in the early 20th century, and which historically holds a particular place of pride in the African diaspora world due to the slave revolution led by Toussaint L'Ouverture in the 1790s. Césaire speaks, thus, of Haiti as being "where négritude stood up for the first time". On the European side, there was also influence and support from the Surrealism movement.

Emergence in the 20th century

During the 1920s and 1930s, a group of young black students and scholars, primarily hailing from France's colonies and territories, assembled in Paris. There they were introduced to the writers of the Harlem Renaissance by Paulette Nardal and her sister Jane. The Nardal Sisters contributed invaluably to the negritude movement both with their writings and by being the proprietors of the Clamart Salon, the tea-shop haunt of the French-Black intelligentsia where the Negritude movement truly began. It was from the Clamart Salon that Paulette Nardal and the Haitian Dr. Leo Sajou founded La revue du Monde Noir (1931–32), a literary journal published in English and French, which attempted to be a mouthpiece for the growing movement of African and Caribbean intellectuals in Paris. This Harlem connection was also shared by the closely parallel development of negrismo in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, and it is likely that there were many influences between the movements, which differed in language but were in many ways united in purpose. At the same time, "Murderous Humanitarianism" (1932) was signed by prominent Surrealists including the Martiniquan surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot and the relationship developed especially with Aimé Césaire.

The actual founders of la Négritude, known as les trois pères (Fr. the three fathers), were originally from three different French colonies in Africa and the Caribbean but they met while living in Paris in the early 1930s.

Aimé Césaire was a poet, playwright, and politician from Martinique. He studied in Paris, where he discovered the black community and "rediscovered Africa". He saw la Négritude as the fact of being black, acceptance of this fact, and appreciation of the history, culture, and destiny of black people. He sought to recognize the collective colonial experience of Blacks - the slave trade and plantation system. He attempted to redefine it. Césaire's ideology defined the early years of la Négritude.

The term négritude (which most closely means "blackness" in English) then was first used in 1935 by Aimé Césaire, in the 3rd issue of L'Étudiant noir, a magazine which he had started in Paris with fellow students Léopold Senghor and Léon Damas, as well as Gilbert Gratiant, Leonard Sainville, and Paulette Nardal. L'Étudiant noir also contains Césaire's first published work, "Negreries", which is notable not only for its disavowal of assimilation as a valid strategy for resistance but also for its reclamation of the word "nègre" as a positive term. "Nègre" previously had been almost exclusively used in a pejorative sense, much like the English word "nigger". Césaire deliberately and proudly incorporated this derogatory word into the name of his movement.

Although each of the pères had his very own ideas about the purpose and styles of la Négritude, the movement was generally characterized by opposing colonialism, the denunciation of Europe's lack of humanity, and the rejection of Western domination and ideas. Also important was the acceptance of and pride in being black and a valorization of African history, traditions, and beliefs. Their literary style was realistic and they cherished Marxist ideas.

Neither Césaire—who after returning to Martinique after his studies in Paris was elected both Mayor of Fort de France, the capital, and a representative of Martinique in France's Parliament—nor Senghor in Senegal envisaged political independence from France. Négritude would, according to Senghor, enable Blacks under French rule to take a "seat at the give and take [French] table as equals". However, France had other ideas, and it would eventually present Senegal and its other African colonies with independence.

Poet and the later first president of Sénégal, Senghor used la Négritude to work toward a universal valuation of African people. He advocated a modern incorporation of the expression and celebration of traditional African customs and ideas. This interpretation of la Négritude tended to be the most common, particularly in later years.

Damas was a French Guyanese poet and National Assembly member. He was called the "enfant terrible" of la Négritude. He had a militant style of defending "black qualities" and rejected any kind of reconciliation with the West.

Reception

In 1948, Jean-Paul Sartre analyzed the négritude movement in an essay called "Orphée Noir" (Black Orpheus) which served as the introduction to a volume of francophone poetry called Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache, compiled by Léopold Senghor. In this essay, Sartre characterizes négritude as the polar opposite of colonial racism in a Hegelian dialectic and with it he helped to introduce Négritude issues to French intellectuals. In his view, négritude was an "anti-racist racism" (racisme antiraciste) necessary to the final goal of racial unity.

Négritude criticized some black writers in the 1960s as insufficiently militant. Keorapetse Kgositsile criticized that the term was based too much on blackness by a white aesthetic, and was unable to define a new kind of black perception that would free black people and black art from white conceptualizations altogether.

The Nigerian dramatist, poet, and novelist Wole Soyinka opposed la Négritude. He believed that by deliberately and outspokenly taking pride in their color, black people were automatically on the defensive: "Un tigre ne proclame pas sa tigritude, il saute sur sa proie" (Fr. A tiger doesn't proclaim its tigerness; it jumps on its prey).

Other uses

American physician Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and early abolitionist, used the term negritude to describe a hypothetical disease which he believed to be a mild form of leprosy, whose only cure was to become white.[3]

Novelist Norman Mailer used the term to describe boxer George Foreman's physical and psychological presence in his book The Fight, a journalistic treatment of the legendary Ali vs. Foreman "Rumble in the Jungle" bout in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) in October 1974.

Stage Oui Be Negroes, an African-American Sketch and Improv company, presented a show entitled "Absolute Negritude" first in Chicago (1999) and then in San Francisco (2000) that explores "the latitude and longitude of “negritude”". (Lawrence Bommer, The Chicago Reader)

See also

References

- ^ Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (2005). "Anténor Firmin and Haiti’s contribution to anthropology". Gradhiva - musée du quai Branly (2005 : Haïti et l'anthropologie): 95–108.

- ^ Murphey, David "Birth of a Nation? The Origins of Senegalese Literature in French", Research in African Literature 39.1 (2008): 48-69. Web. 9 Nov 2009. <https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=28628450&site=ehost-live&scope=site>.

- ^ Vernellia R. Randall. "An Early History - African American Mental Health". http://academic.udayton.edu/health/01status/mental01.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Orphée Noir". Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache. ed. Léopold Senghor. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. p. xiv (1948).

- Condé, Maryse (1998), "O Brave New World", Research in African Literatures 29: 1–7, http://www.awigp.com/default.asp?numcat=conde.

Bibliography

Original texts

- Césaire, Aimé: Return to My Native Land, Bloodaxe Books Ltd 1997, ISBN 1852241845

- Césaire, Aimé: Discourse on Colonialism, Monthly Review Press 2000 (orig. 1950), ISBN 1583670254

- Damas, Léon-Gontran, Poètes d'expression française.Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1947

- Diop, Birago, Leurres et lueurs. Paris: Présence Africaine, 1960

- Senghor, Léopold Sedar, The Collected Poetry, University of Virginia Press, 1998

- Senghor, Léopold Sédar, Ce que je crois. Paris: Grasset, 1988

- Tadjo, Véronique, Red Earth/Latérite. Spokane, Washington: Eastern Washington University Press, 2006

Secondary literature

- T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Negritude Women, University of Minnesota Press 2002, ISBN 081663680X

- Christian Filostrat, Negritude Agonistes, Africana Homestead Legacy Publishers 2008, ISBN 9780981893921

- Gary Wilder, The French Imperial Nation-State: Negritude & Colonial Humanism Between the Two World Wars, University of Chicago Press 2005, ISBN 0226897729

- Thompson, Peter, Negritude and Changing Africa: An Update, in Research in African Literatures, Winter, 2002

- Thompson, Peter, Négritude et nouveaux mondes—poésie noire: africaine, antillaise et malgache. Concord, Mass: Wayside Publishing, 1994

Still Relevant:

- Georges Balandier, "La Situation Coloniale: Approche Théorique", Cahiers internationaux de sociologie, XI (1951):44-79. English translation by Robert A Wagoner, as "The Colonial Situation: A Theoretical Approach (1951) in Immanuel Wallerstein, ed. Social Change; The Colonial Situation (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1966): 34-61

Filmography

- Négritude : Naissance et expansion du concept a documentary by Nathalie Fave et Jean-Baptiste Fave, with the interventions of Amadou Lamine Sall, Racine Senghor, Lylian Kesteloot, Jean-Louis Roy, Jacqueline Lemoine, Gérard Chenêt, Victor Emmanuel Cabrita, Nafissatou Dia Diouf, Amadou Ly, Youssoufa Bâ, Raphaël Ndiaye, Alioune Badara Bèye, Hamidou Dia, Georges Courrèges, Baba Diop ; Maison Africaine de la Poésie Internationale, Shoot at Sénégal in 2005, 56' (DVD) : first minutes online

Schools of Poetry Akhmatova's Orphans · Auden Group · The Beats · Black Arts Movement · Black Mountain poets · British Poetry Revival · Cairo poets · Castalian Band · Cavalier poets · Chhayavaad · Churchyard poets · Confessionalists · Créolité · Cyclic poets · Dadaism · Deep image · Della Cruscans · Dolce Stil Novo · Dymock poets · The poets of Elan · Flarf · Fugitives · Garip · Gay Saber · Generation of '98 · Generation of '27 · Georgian poets · Goliard · The Group · Harlem Renaissance · Harvard Aesthetes · Hungry Generation · Imagism · Informationist poetry · Jindyworobak · Lake Poets · Language poets · Martian poetry · Metaphysical poets · Misty Poets · Modernist poetry · The Movement · Négritude · New American Poetry · New Apocalyptics · New Formalism · New York School · Objectivists · Others group of artists · Parnassian poets · La Pléiade · Rhymers' Club · San Francisco Renaissance · Scottish Renaissance · Sicilian School · Sons of Ben · Southern Agrarians · Spasmodic poets · Sung poetry · Surrealism · Symbolism · Uranian poetryCategories:- Literary movements

- Postcolonialism

- Pan-Africanism

- African and Black nationalism

- Latin American literature

- French West Africa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.