- Joseph Francis Shea

Infobox Person

name = Joseph Francis Shea

image_size = 200px

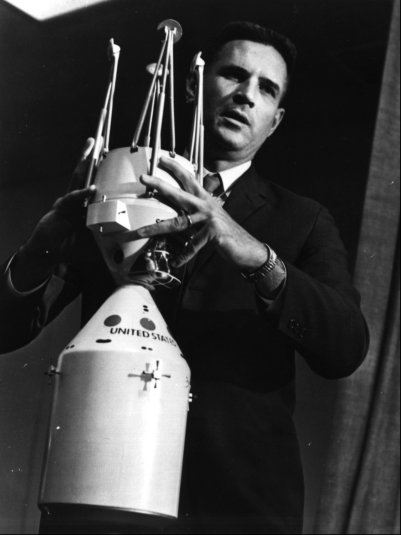

caption = Shea demonstrates a docking between the Apollolunar module and command module

birth_date = birth date|1925|9|5|mf=y

birth_place =The Bronx ,New York , USA

death_date= death date and age|1999|2|14|1925|9|5|mf=y

death_place= Weston,Massachusetts , USA

occupation =NASA managerJoseph Francis Shea (September 5, 1925 – February 14, 1999) was an American

aerospace engineer andNASA manager. Born in theNew York City borough ofthe Bronx , he was educated at theUniversity of Michigan , receiving a Ph.D. in Engineering Mechanics in 1955. After working forBell Labs on the radioinertial guidance system of theTitan I intercontinental ballistic missile , he was hired by NASA in 1961. As Deputy Director of NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight, and later as head of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, Shea played a key role in shaping the course of the Apollo program, helping to lead NASA to the decision in favor oflunar orbit rendezvous and supporting "all up" testing of theSaturn V rocket. While sometimes causing controversy within the agency, Shea was remembered by his former colleague George Mueller as "one of the greatest systems engineers of our time".Mueller, "Joseph F. Shea," in "Memorial Tributes: National Academy of Engineering, Volume 10", p. 211.]Deeply involved in the investigation of the 1967

Apollo 1 fire, Shea suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of the stress that he suffered. He was removed from his position and left NASA shortly afterwards. From 1968 until 1990 he worked as a senior manager atRaytheon inLexington, Massachusetts , and thereafter became an adjunct professor ofaeronautics andastronautics atMIT . While Shea served as a consultant for NASA on the redesign of theInternational Space Station in 1993, he was forced to resign from the position due to health issues.Early life and education

Shea was born and grew up in

the Bronx ,New York , the eldest son in aworking-class Irish Catholic family. His father worked as a mechanic on the New York subways. As a child, Shea had no interest in engineering; he was a good runner and hoped to become a professional athlete. He attended a Catholichigh school and graduated when he was only sixteen years of age.Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 121.]On graduating in 1943, Shea enlisted in the Navy and enrolled in a program that would put him through college. He began his studies at

Dartmouth College , later moving to MIT and finally to theUniversity of Michigan , where he would remain until he earned his doctorate in 1955. In 1946, he was commissioned as an ensign in the Navy and received a Bachelor of Science degree in Mathematics. Shea went on to earn an MSc (1950) and a Ph.D. (1955) in Engineering Mechanics from the University of Michigan. While earning his doctorate, Shea found the time to teach at the university and to hold down a job atBell Labs . [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 121. Mueller, "Joseph F. Shea," in "Memorial Tributes: National Academy of Engineering, Volume 10", p. 211.]ystems engineer

After receiving his doctorate, Shea took a position at Bell Labs in

Whippany, New Jersey . There he first worked as the system engineer on the radioguidance system of theTitan I intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and then as the development and program manager on theinertial guidance system of theTitan II ICBM.Mueller, "Joseph F. Shea," in "Memorial Tributes: National Academy of Engineering, Volume 10", p. 212.] Shea's specialty wassystems engineering , a new type of engineering developed in the 1950s that focused on themanagement and integration of large-scale projects, turning the work of engineers andcontractor s into one functioning whole. He played a significant role in the Titan I project; as George Mueller writes, " [H] e contributed a considerable amount of engineering innovation andproject management skill and was directly responsible for the successful development of this pioneeringguidance system ." In addition to Shea's technical abilities, it quickly became obvious that he was also an excellent manager of people. Known for his quick intellect, he also endeared himself to his subordinates through small eccentricities such as his fondness for badpuns and habit of wearing red socks to important meetings. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 122.] During the critical days of the Titan project Shea moved into the plant, sleeping on a cot in his office so as to be available at all hours if he was needed.Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 123.]Having brought in the project on time and on budget, Shea established a reputation in the aerospace community. In 1961 he was offered and accepted a position with Space Technology Laboratories, a division of

TRW Inc., where he continued to work onballistic missile systems.cite web

title = Joseph F. Shea

work = NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Biographical Data Sheet

url = http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_Bio.pdf

format =PDF ]NASA career

In December 1961, NASA invited Shea to interview for the position of deputy director of the Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF). Brainerd Holmes, the director of the OMSF, had been searching for a deputy who could offer expertise in systems engineering, someone with the technical abilities to supervise the Apollo program as a whole. Shea was recommended by one of Holmes' advisors, who had worked with him at Bell Labs. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 120–1.] Although Shea had worked at Space Technology Labs for less than a year, he was captivated by the challenge offered by the NASA position. "I could see they needed good people in the space program," he later said, "and I was kind of cocky in those days." [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 123.]

Lunar orbit rendezvous

When Shea was hired by NASA, President

John F. Kennedy 's commitment to landing men on the moon was still only seven months old, and many of the major decisions that shaped the Apollo program were yet to be made. Foremost among these the mode that NASA would use to land on the moon. When Shea first began to consider the issue in 1962, most NASA engineers and managersemdashincludingWernher von Braun , the director of theMarshall Space Flight Center emdashfavored either an approach calleddirect ascent , where the Apollo spacecraft would land on the moon and return to the earth as one unit, orearth orbit rendezvous , where the spacecraft would be assembled while still in orbit around the earth. However, dissenters such asJohn Houbolt , a Langley engineer, favored an approach that was then considered to be more risky. This waslunar orbit rendezvous , in which the landing on the moon would be accomplished using two spacecraft: acommand module that remained inorbit around the moon, and alunar module that descended to the moon and then returned to dock with the command module while in lunar orbit. [Hansen, "Enchanted Rendezvous", "passim".]In November 1961, John Houbolt had sent a paper advocating lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) to

Robert Seamans , the deputy administrator of NASA. As Shea remembered, "Seamans gave a copy of Houbolt's letter to Brainerd Holmes [the director of OMSF] . Holmes put the letter on my desk and said, "Figure it out." [Shea, [http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_8-26-98.pdf Oral History] (PDF), August 26, 1998, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, p. 1.] Shea became involved in the lunar orbit rendezvous decision as a result of this letter. While he began with a mild preference for earth orbit rendezvous, Shea "prided himself," according to space historians Murray and Cox, "on going wherever the data took him." [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 124.] In this case, the data took him to NASA'sLangley Research Center inHampton, Virginia , where he met with John Houbolt and with theSpace Task Group , and became convinced that LOR was an option worth considering.Hansen, "Enchanted Rendezvous", p. 23.]Shea's task now became to shepherd NASA to a firm decision on the issue. This task was complicated by the fact that he had to build consensus between NASA's different centersemdashmost notably the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston headed by

Robert Gilruth , and theMarshall Space Flight Center inHuntsville, Alabama , headed byWernher von Braun . Relations between the centers were not good, and it was a major milestone in the progress of the Apollo program when von Braun and his team finally came to accept the superiority of the LOR concept. NASA announced its decision at a press conference on July 11, 1962, only six months after Shea had joined NASA. Space historian James Hansen concludes that Shea "played a major role in supporting Houbolt's ideas and making the... decision in favor of LOR," while his former colleague George Mueller writes that "it is a tribute to Joe's logic and leadership that he was able to build a consensus within the centers at a time when they were autonomous." [Mueller, quoted in Rosen, "Apollo 11 remembered," "Aerospace America", November 1994, p. B7.]During his time at the OMSF, Shea helped to resolve many of the other inevitable engineering debates and conflicts that cropped up during the development of the Apollo spacecraft. In May 1963, he formed a Panel Review Board, bringing together representatives of the many committees that aimed to coordinate work between NASA centers. Under Shea's leadership, this coordination became far more efficient. [Brooks, Grimwood and Swenson, "Chariots for Apollo", pp. 122–3]

Program manager

In October 1963, Shea became the new manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO) in Houston. Although technically a demotion, this new position gave Shea the responsibility for managing the design and construction of the Apollo command and

lunar module s. Of particular concern to Shea was the performance ofNorth American Aviation , the contractor responsible for the command module. As he later recounted:I do not have a high opinion of North American and their motives in the early days. Their first program manager was a first-class jerk.... There were spots of good guys, but it was just an ineffective organization. They had no discipline, no concept of change control. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 170.]

It was Shea's responsibility to bring that engineering discipline to North American and to NASA's management of its contractors. His systems management experience served him well in his new post. In the coming years, any change to the design of the Apollo spacecraft would have to receive its final approval from Joe Shea. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 174.] He kept control of the program using a management tool that he devised for himself—a looseleaf notebook, more than a hundred pages in length, that would be put together for him every week summarizing all of the important developments that had taken place and decisions that needed to be made. Presented with the notebook on Thursday evenings, Shea would study and annotate it over the weekend and return to work with new questions instructions, and decisions. This idiosyncratic tool allowed him to keep tabs on a complex and ever-expanding program. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 172–3.]Shea's relationship with the engineers at North American was a difficult one. While Shea blamed North American's management for the continuing difficulties in the development of the command module, project leader

Harrison Storms felt that NASA itself was far from blameless. It had delayed in making key design decisions, and persisted in making significant changes to the design once construction had begun. While Shea did his part in attempting to control the change requests, Storms felt that he did not understand or sympathize with the inevitable problems involved in the day-to-day work of manufacturing. [Gray, "Angle of Attack", pp. 184, 188.]Shea was a controversial figure even at the Manned Spacecraft Center. Not having been at Langley with the Space Task Group, he was considered an "outsider" by men such as flight director

Chris Kraft . Kraft recalled that "the animosity between my people and Shea's was intense." [Kraft, "Flight", p. 251.] Relations between Shea and other NASA centers were even more fraught. As the deputy director of OMSF, Shea had sought to extend the authority of NASA Headquarters over the fiercely independent NASA centers. This was particularly problematic when it came to the Marshall Space Flight Center, which had developed its own culture under Wernher von Braun. Von Braun's philosophy of engineering differed from Shea's, taking a consensual rather than top-down approach. As one historian recounts, von Braun felt that "Shea had 'bitten off' too much work and was going to 'wreck' the centers engineering capabilities." [Sato, "Local Engineering and Systems Engineering," "Technology and Culture", July 2005, p. 576.]The friction between Shea and Marshall, which had begun when Shea was at OMSF, continued after he moved to his new position. He became deeply involved in supporting George Mueller's effort to impose the idea of "all up" testing of the

Saturn V rocket on the unwilling engineers at Marshall. Von Braun's approach to engineering was a conservative one, emphasizing the incremental testing of components. But the tight schedule of the Apollo program didn't allow for this slow and careful process. What Mueller and Shea proposed was to test the Saturn V as one unit on its very first flight, and Marshall only reluctantly came to accept this approach in late 1963. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 158, 162.] When later asked how he and Mueller had managed to sell the idea to von Braun, Shea responded that "we just told him that's the way it's going to be, finally." [Shea, [http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_8-26-98.pdf Oral History] (PDF), August 26, 1998, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, p. 7.]Shea's role in resolving differences within NASA, and between NASA and its contractors, placed him in a position where criticism was inevitable. However, even Shea's critics could not help but respect his engineering and management skills. Everyone who knew Shea considered him to be a brilliant engineer, [Gray, "Angle of Attack", p. 188. Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 121.] and his time as manager at ASPO only served to solidify a reputation that had been formed during his time on the Titan project. Of Shea's work in the mid-1960s, Murray and Cox write that "these were Joe Shea's glory days, and whatever the swirl of opinions about this gifted, enigmatic man, he was taking an effort that had been foundering and driving it forward." [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 178.] Shea's work also won wider attention, bringing him public recognition that approached that accorded to Wernher von Braun or Chris Kraft. Kraft had appeared on the cover of "Time" in 1965; "Time" planned to offer Shea the same honor in February 1967, the month in which the first manned Apollo mission was scheduled to occur.Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 186.]

Apollo 1 fire

Background

Problems with the Apollo command module continued through the testing phase. The review meeting for the first spacecraft intended for a manned mission took place on August 19, 1966. One issue of concern was the amount of

Velcro in the cabin, a potential fire hazard in the pure-oxygen atmosphere of the spacecraft, if there were to be a spark. As Shea later recounted:And so the issue was brought up at the acceptance of the spacecraft, a long drawn-out discussion. I got a little annoyed, and I said, "Look, there's no way there's going to be a fire in that spacecraft unless there's a spark or the astronauts bring cigarettes aboard. We're not going to let them smoke." Well, I then issued orders at that meeting, "Go clean up the spacecraft. Be sure that all the fire rules are obeyed." [Shea, [http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_11-23-98.pdf Oral History] (PDF), November 23, 1998, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, p. 16.]

Although the spacecraft passed its review, the crew finished the meeting by presenting Joe Shea with a picture of the three of them seated around a model of the capsule, heads bowed in prayer. The inscription was simple:

It isn't that we don't trust you, Joe, but this time we've decided to go over your head." [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 184.]

On January 25, 1967, the

Apollo 1 crew began a series of countdown tests in the spacecraft on the pad atKennedy Space Center . Although Shea had ordered his staff to direct North American to take action on the issue of flammable materials in the cabin, he had not supervised the issue directly, and little if any action had been taken. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 185.] During pad testing, the spacecraft suffered a number of technical problems, including broken and static-filled communications.Wally Schirra , the backup commander for the mission, suggested to Shea that he should go through the countdown test in the spacecraft with the crew in order to experience first-hand the issues that they were facing. Although Shea seriously considered the idea, it proved to be unworkable because of the difficulties of hooking up a fourth communications loop for Shea. The hatch would have to be left open in order to run the extra wires out, and leaving the hatch open would make it impossible to run the emergency egress test that had been scheduled for the end of the day on the 27th. [Gray, "Angle of Attack", pp. 226–7.] As Shea later told the press, joining the crew for the test "would have been highly irregular". ["2 Space Aides Decided Not to Join Apollo Test," "The New York Times", February 12, 1967, p. 32.]The final countdown test took place on January 27. While Shea was in Florida for the beginning of the test, he decided to leave before it concluded. He arrived back at his office in Houston at about 5:30 p.m. CST. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 188.] At 5:31 p.m. CST (6:31 p.m. EST) a massive fire broke out in the Apollo command module. Unable to escape, the three astronauts inside the spacecraftemdash

Gus Grissom , Ed White andRoger Chaffee emdashwere killed within seconds.Investigation

Immediately after the fire, Shea and his ASPO colleagues at Houston boarded a NASA plane to the Kennedy Space Center. They landed at about 1:00 a.m., only five hours after the fire had broken out. At a meeting that morning with

Robert Gilruth , George Mueller andGeorge Low , Shea helped to determine the individuals who would be on the NASA review board looking into the causes of the fire. Additionally, he persuaded George Mueller, head of NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight, to allow him to act as Mueller's deputy in Florida, supervising the progress of the investigation. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 206–11.]Named to the advisory group chosen to support the review board, [Ertel and Newkirk, "Apollo Spacecraft", Vol IV, p. 70.] Shea threw himself into the investigation, working eighty-hour weeks. [Gray, "Angle of Attack", p. 238.] Although the precise source of ignition was never found, it soon became clear that an

electrical short somewhere in the command module had started the fire, probably sparked by a chafed wire. What was less clear was where to apportion responsibility. NASA engineers tended to point to what they saw as shoddy workmanship by North American Aviation. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 214–15.] By contrast, North American executives blamed NASA management for its decision over their objections to pressurize the command module with pure oxygen to a pressure far in excess of that needed in space, in which almost any materialemdashincluding Velcro, with which the cabin was filledemdashwould instantly burst into flames if exposed to a spark. [Gray, "Angle of Attack", p. 245.] Whatever the precise distribution of responsibility, Joseph Shea remained haunted by the feeling that he, personally, was responsible for the deaths of three astronauts. For years after the fire, he displayed the portrait given to him by the Apollo 1 crew in the front hallway of his own home. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 225.]Breakdown

The pressure of the investigation took a psychological toll on Shea. He had trouble sleeping and began to resort to

barbiturates and alcohol in order to help him cope. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", pp. 213–14.] Shea was not the only NASA employee who found the aftermath of the fire difficult to handle: Robert Seamans wrote that "key people from Houston would fly up to Washington to testify and literally sob all the way on the plane", [Seamans, "Aiming at Targets", p. 139.] and a man who worked under Shea suffered a nervous breakdown and was reportedly taken to a mental hospital in astraitjacket . [O'Toole and Schefter, "The Bumpy Road," "The New York Times", July 15, 1979, p. E1.] A few weeks after the fire, Shea's colleagues began to notice that he too was behaving erratically. Chris Kraft, whose father had suffered fromschizophrenia , later related Shea's behavior in one meeting:Joe Shea got up and started calmly with a report on the state of the investigation. But within a minute, he was rambling, and in another thirty seconds, he was incoherent. I looked at him and saw my father, in the grip of

NASA administrator James Webb became increasingly worried about Shea's mental state. Specifically, he was concerned that Shea might not be able to deal with the hostile questioning that he would receive from the congressional inquiry into the Apollo 1 fire. Senatordementia praecox . It was horrifying and fascinating at the same time. [Kraft, "Flight", p. 275.]Walter Mondale had accused NASA engineers of "criminal negligence " with regard to the design and construction of the Apollo command module, and it was reliably expected that Shea would be in the firing line. In March, Webb sent Robert Seamans and Charles Berry, NASA's head physician, to speak with Shea and ask him to take an extended voluntaryleave of absence . This would, they hoped, protect him from being called to testify. Apress release was already prepared, but Shea refused to accept this "fait accompli", threatening to resign rather than take leave. As a compromise, he agreed to meet with a psychiatrist and to abide by an independent assessment of his psychological fitness. Yet this approach to removing Shea from his position was also unsuccessful. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 217–19.] As one of his friends later recounted:The psychiatrists came back saying, 'He's so smart, he's so intelligent!' Here Joe was, ready to kill himself, but he could still outsmart the psychiatrists. [Murray and Cox, "Apollo", p. 219.]

Reassignment

Finally Shea's superiors were forced to take a more direct approach. On April 7 it was announced that Shea would be moving to NASA Headquarters in

Washington, D.C. , where he would serve as George Mueller's deputy at the Office of Manned Space Flight. He was replaced as chief of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office byGeorge Low . [Ertel and Newkirk, "Apollo Spacecraft", Vol IV, p. 119.] While Shea had already acted as Mueller's "de facto" deputy in Florida during the investigation, the reality of this permanent posting was very different. When Shea's reassignment was announced, one of his friends gave an anonymous interview to "Time" magazine in which he said that "if Joe stays in Washington, it'll be a promotion. If he leaves in three or four months, you'll know this move amounted to being fired. ["How Soon the Moon?", "Time", April 14, 1967.]Shea himself accepted the re-assignment only reluctantly, feeling that "it was as if NASA was trying to hide me from the Congress for what I might have said".Shea, [http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_11-23-98.pdf Oral History] (PDF), November 23, 1998, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, p. 18.] Once in the job, he grew increasingly dissatisfied with a posting that he considered to be a "non-job", later commenting that "I don't understand why, after everything I had done for the program ... I was only one that was removed. That's the end of the program for me." [Shea, [http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SheaJF/SheaJF_11-23-98.pdf Oral History] (PDF), November 23, 1998, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, p. 17.] Only six months after the fire, and some two months after taking his new position, Shea left NASA in order to become a Vice President at the

Polaroid Corporation inWaltham, Massachusetts . He had not been called to testify before the congressional inquiry into the fire.Post-NASA career

In 1968, Shea took a position at

Raytheon inLexington, Massachusetts . He would remain with the company until his retirement in 1990, serving as Senior Vice President for Engineering from 1981 through 1990. After leaving Raytheon, Shea became an adjunct professor of aeronautics and astronautics atMIT .In February 1993, NASA administrator

Daniel Goldin appointed Shea to the chairmanship of a technical review board convened to oversee the redesign of the troubledInternational Space Station project. [Sawyer, "NASA Picks Manager to Cut Expenditures on Space Station," "The Washington Post", February 27, 1993, p. A2.] However, Shea was hospitalized shortly after his appointment. By April he was well enough to attend a meeting where the design team formally presented the preliminary results of its studies, but his behavior at the meeting again called his capacities into question. As "The Washington Post" reported:Shea made a rambling, sometimes barely audible two-hour presentation that left many of those present speculating about his ability to do the job. A longtime friend said, "That's not the real Joe Shea. He is normally incisive and well-organized."cite news |first= |last= |authorlink= |coauthors= |title=Space Station Redesign Chief Steps Down |url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-943331.html |quote= |work=

On the day following the meeting, Shea offered his resignation, becoming instead a special advisor to Daniel Goldin. NASA reported that he had resigned due to health reasons. However, "The Scientist" offered a different interpretation, quoting sources who speculated that the bluntness of his speech, including criticisms of Goldin, may have been controversial in NASA circles.Veggeberg, "President to Space Station," vol 7, issue 10, p. 3.]Washington Post |date=April 23, 1993 |accessdate=2008-07-29 ]

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.