- History of Germany during World War II

-

This article is about the combat history of Nazi Germany. For other national history through the period (domestic activity, war production, etc.), see Germany in World War II.

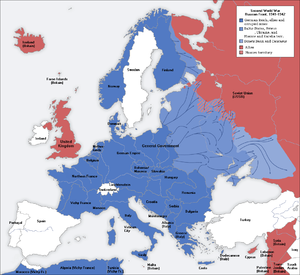

The history of Germany during World War II closely parallels that of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. He came to power in Germany in 1933. From that point onward, Germany followed a policy of rearmament and confrontation with other countries. During the war German armies occupied most of Europe; Nazi forces defeated France, took Norway, invaded Yugoslavia and Greece and occupied much of the European portion of the Soviet Union. Germany also forged alliances with Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and later Finland and collaborated with individuals in several other nations. The German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942 was considered the decisive victory that turned the tide of the war against Germany and her Anti-Comintern allies.[1] The Second World War culminated in Germany's unconditional surrender to the Allies, the fall of Nazi Germany, and the death of Adolf Hitler.

Contents

Invasion of Poland

Main article: Invasion of PolandOn 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland which led to World War II and then Britain and France declared war on Germany, in accordance with the agreement that they had with Poland. Following Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and India also declared war on Germany. After the end of the campaign in Poland, the war entered a period of relative inactivity known as the "Phoney War". This ended when Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in April 1940 (see Operation Weserübung) and the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France in May (see Battle of France). All of the invaded countries swiftly capitulated and the forces of Britain and its allies suffered a humiliating defeat in Norway (see Allied campaign in Norway) and a near-disastrous retreat from France (see Battle of Dunkirk). Britain was threatened with an amphibious invasion (see Operation Sea Lion), but during the Battle of Britain the Luftwaffe failed to achieve air superiority, so the invasion was postponed indefinitely. One piece of British territory, the Channel Islands, was occupied by Germany until the end of the war.

North Africa

In June 1940, after the Battle for France was all but over, Italy joined Germany and dictator Benito Mussolini declared war on Britain and France. In August, Italian colonial forces took the initiative; from their colony in East Africa they occupied British Somaliland. In September, they also staged a limited invasion of Egypt from Libya. The British and Commonwealth forces, despite being outnumbered by 500,000 available troops to 35,000 (of whom 17,000 were non-combatants), made a fighting withdrawal after reinforcements were sent to the region in December and counterattacked. The British dealt out several humiliating defeats to the Italians and captured over 130,000 prisoners in a two-month campaign in eastern Libya. In January 1941, the Afrika Korps were sent to Libya to reinforce their Italian allies and a hard fought campaign ensued. This part of the war is known as the North African Campaign.

South Eastern Europe

Main articles: Battle of Greece and Invasion of YugoslaviaThe Italian invasion of Greece in November 1940 was a disaster and Italian forces were driven back into Albania, which Italy had occupied in 1939. Nazi Germany attacked Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941 to assist their allies and prevent any possibility of disruption to the production of oil from their oilfields by hostile forces.

Soviet Union

Main article: Operation BarbarossaThe Soviet Union invaded Poland together with Nazi Germany in 1939 in accordance with the secret part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and remained outside the main conflict for two years, Stalin assuming that he was safe from an attack from Hitler, not wishing to fight a war on two fronts.

For the Germans and the British, however, the war in the West was seen as only the overture to the great operations against Communist Russia. The successful campaigns against Poland, Scandinavia and France, and the bad standing of the Red Army after the Great Purge in the 1930s, as indicated by the fiasco of the Winter War, made Hitler believe that relations between Nazi Germany and Russia would not again be as favorable. This crusade against Bolshevism (as Hitler saw it), codenamed Operation Barbarossa, was to be launched sooner rather than later. It was planned to unite Western Europe behind Nazi Germany's leadership for the common goal (to fight Communism).

The German campaigns in Greece and North Africa delayed the planned invasion by several weeks, and a great deal of the good summer weather was already lost by the time the invasion was launched on 22 June 1941. The massive attack still turned out to be an initial success, conquering whole areas of the Soviet Union's western region. Their only significant strategic failure was the advance on Moscow, which was halted by stiff resistance, and subsequently driven back by a Russian counter-attack. The following years, however, were less successful on the Eastern Front.

Italian Armistice and loss of the Allies

The German and Italian defeat in North Africa allowed the Allied forces to contemplate opening up a new theater in the south. Sicily was invaded in July 1943 leading to the overthrow and imprisonment of Mussolini. In September, the Italian mainland was invaded. Shortly afterward, an armistice was signed and Italian troops found themselves arrested and imprisoned by the Germans. The Germans fought on in Italy, and in October the new Italian government declared war on Germany. The campaign in Italy eventually bogged down as the focus of attention for the Western Allies was drawn to opening up a new front in northern France.

One by one, Germany's other allies left the war. Throughout 1944, the governments of Romania, Bulgaria, and Finland found ways to change sides.

War crimes

Many units of the German army actively participated in war crimes, such as the massacre of prisoners and the civilian population, especially on the Eastern front. Those actions were in addition to the massacres carried out by the Einsatzgruppen who were specifically detailed to kill innocent civilians and Jews. The Einsatzgruppen were assisted by other Axis forces, including designated members of the Wehrmacht, including generals Walther von Reichenau and Erich von Manstein, as well as the Waffen-SS. For example, von Manstein issued an order on 20 November 1941: his version of the infamous "Reichenau Order", which equated "partisans" and "Jews" and called for draconian measures against them. Hitler commended the "Reichenau Order" as exemplary and encouraged other generals to issue similar orders. Von Manstein was among the minority that voluntarily issued such an order. It stated that:

This struggle is not being carried on against the Soviet Armed Forces alone in the established form laid down by European rules of warfare.

Behind the front too, the fighting continues. Partisan snipers dressed as civilians attack single soldiers and small units and try to disrupt our supplies by sabotage with mines and infernal machines. Bolshevists left behind keep the population freed from Bolshevism in a state of unrest by means of terror and attempt thereby to sabotage the political and economic pacification of the country. Harvests and factories are destroyed and the city population in particular is thereby ruthlessly delivered to starvation.

Jewry is the middleman between the enemy in the rear and the remains of the Red Army and the Red leadership [who are] still fighting. More strongly than in Europe they hold all key positions of political leadership and administration, of trade and crafts and constitutes a cell for all unrest and possible uprisings.

The Jewish Bolshevik system must be wiped out once and for all and should never again be allowed to invade our European living space.

The German soldier has therefore not only the task of crushing the military potential of this system. He comes also as the bearer of a racial concept and as the avenger of all the cruelties which have been perpetrated on him and on the German people.

...

The soldier must appreciate the necessity for the harsh punishment of Jewry, the spiritual bearer of the Bolshevik terror. This is also necessary in order to nip in the bud all uprisings which are mostly plotted by Jews.[2]In the Baltic states and Ukraine, they also recruited local collaborators - Hiwis to assist in the killing. Such behavior was officially sanctioned and two heads of the army, Generals Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, were prosecuted at the Nuremberg Trials. They were both found guilty and executed.

On the defensive

German forces surrender to Canadians at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

German forces surrender to Canadians at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

In the east, the Germans had been steadily withdrawing in the face of increasingly capable Red Army offensives. After the Battle of Kursk in July 1943, the Reich arsenal was deprived of many important armored vehicles and Germany was unable to launch another serious offensive in the east. At the time of the D-Day invasion on 6 June 1944, German forces were thinly stretched across three fronts. By August 1944, Soviet forces had crossed into parts of eastern Germany and in December, the last ditch Ardennes Offensive ground to a halt in the west due to a lack of supplies and bitter allied opposition.

Defeat

Allied forces established a bridgehead on the Rhine in March 1945, the Battle of Berlin began on 16 April. A planned last defense from the Alpenfestung ("Alpine Fortress") never happened. Hitler's demolitions on Reich Territory order was largely ignored. Hitler shot himself and ordered his assistant to burn his body, he also appointed Karl Dönitz as his successor. Berlin surrendered on the night of May 2-3, the German Instrument of Surrender was signed on May 7. The members of the provisional government were arrested on May 23 and subsequently found guilty of war crimes at Nuremberg.

See also

- Mass suicides in 1945 Nazi Germany

- German prisoners of war in the United States

References and notes

- ^ "...among the decisive battles in the long history of war". Editorial The New York Times, 2 February 1943, quoted in Roberts, Geoffrey (2002), Victory at Stalingrad: The Battle that Changed History page 4. London: Pearson. ISBN 0-582-77185-4

- ^ Nuremberg trials proceedings, Vol. 20, pp. 639–645

- Calvocoressi, Peter and Guy Wint. Total War New York, New York Penguin press, 2001

- Keegan, John. The Second World War. New York Penguin press, 1990

- Lubbeck, William and David B. Hurt. "At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North.", Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2006 (ISBN 1-932033-55-6).

World War II Participants Timeline Aspects GeneralWar crimes- German and Wehrmacht war crimes

- The Holocaust

- Italian war crimes

- Japanese war crimes

- Unit 731

- Allied war crimes

- Soviet war crimes

- United States war crimes

- German military brothels

- Camp brothels

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- Comfort women

- Rape of Nanking

- Rape during the occupation of Germany

- Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs

- Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Japanese prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Japanese prisoners of war in World War II

- German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Finnish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Polish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Romanian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- German prisoners of war in the United States

Categories:- Military history of Germany during World War II

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.