- Equal pay for women

-

Equal pay for women is an issue regarding pay inequality between men and women. It is often introduced into domestic politics in many first world countries as an economic problem that needs governmental intervention via regulation. The Equal Remuneration Convention requires its over 160 states parties to have equal pay for men and women.

Contents

Gender pay gap

Main article: Gender pay gapThe 2008 edition of the Employment Outlook report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that women are paid 17% less than their male counterparts. Moreover the report argued that labor market discrimination continues to be a problem and that "30% of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labour market."[2][3]

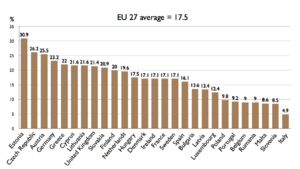

Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5 % on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008. There were considerable differences between the Member States, with the pay gap ranging from less than 10% in Italy, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Belgium to more than 20% in Slovakia, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, United Kingdom and Greece and more than 25% in Estonia and Austria.[1]

A report commissioned by the International Trade Union Confederation in 2008 shows that, based on their survey of 63 countries, there is a significant gender pay gap of 15.6 %. Excluding Bahrain, where a positive gap of 40% is shown (due possibly to very low female participation in paid employment), the global figure is 16.5%. Women who are engaged in work in the informal economy have not been included in these figures. Overall, throughout the world, the figures for the gender pay gap range from 13% to 23%. The report found that women are often educated equally high as men, or to a higher level but "higher education of women does not necessarily lead to a smaller pay gap, however, in some cases the gap actually increases with the level of education obtained". The report also argues that this global gender pay gap is not due to lack of training or expertise on the part of women since "the pay gap in the European Union member states increases with age, years of service and education".[4][5]

Situation by country

Australia

Main article: Gender pay gap in AustraliaUnder Australia's old centralised wage fixing system, "equal pay for work of equal value" by women was introduced in 1969. Anti-discrimination on the basis of sex was legislated in 1984.[6]

In November 2011, Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced efforts by the national government to improve salaries of the 150,000 lowest-paid workers in Australia, roughly 120,000 women, by contributing AU$2 billion over the next 6 years.[7]

Canada

In Canadian usage, the terms pay equity and pay equality are used somewhat differently than in other countries. The two terms refer to distinctly separate legal concepts.

Pay equality, or equal pay for equal work, refers to the requirement that men and women be paid the same if performing the same job in the same organization. For example, a female electrician must be paid the same as a male electrician in the same organization. Reasonable differences are permitted if due to seniority or merit.

Pay equality is required by law in each of Canada’s 14 legislative jurisdictions (ten provinces, three territories, and the federal government). Note that federal legislation applies only to those employers in certain federally-regulated industries such as banks, broadcasters, and airlines, to name a few. For most employers, the relevant legislation is that of the respective province or territory.

For federally-regulated employers, pay equality is guaranteed under the Canadian Human Rights Act.[8] In Ontario, pay equality is required under the Ontario Employment Standards Act.[9] Every Canadian jurisdiction has similar legislation, although the name of the law will vary.

In contrast, pay equity, in the Canadian context, means that male-dominated occupations and female-dominated occupations of comparable value must be paid the same if within the same employer. The Canadian term pay equity is referred to as “comparable worth” in the US. For example, if an organization’s nurses and electricians are deemed to have jobs of equal importance, they must be paid the same. One way of distinguishing the concepts is to note that pay equality addresses the rights of women employees as individuals, whereas pay equity addresses the rights of female-dominated occupations as groups.

Certain Canadian jurisdictions have pay equity legislation while others do not, hence the necessity of distinguishing between pay equity and pay equality in Canadian usage. For example, in Ontario, pay equality is guaranteed through the Ontario Employment Standards Act[9] while pay equity is guaranteed through the Ontario Pay Equity Act.[10] On the other hand, the three westernmost provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan) have pay equality legislation but no pay equity legislation. Some provinces (for example, Manitoba) have legislation that requires pay equity for public sector employers but not for private sector employers; meanwhile, pay equality legislation applies to everyone.

Ireland

In Ireland, the Anti-Discrimination (Pay) Act was passed in 1974 and came into force in 1977.

United Kingdom

Main article: Equal Pay Act 1970The Equal Pay Act of 1970 was passed by the United Kingdom Parliament to prevent discrimination as regards to terms and conditions of employment between men and women, following the 1968 Ford sewing machinists strike. A similar act to these was passed in France in 1972. These reflected Article 119 of the original EEC Treaty, which started: "Each Member State shall in the course of the first stage ensure and subsequently maintain the application of the principle of equal remuneration for equal work as between men and women workers."

United States

In the United States, women make roughly 77.8 cents to the dollar.[11] Economists expect that in a free market, managers would prefer to hire less costly women workers, forcing men to compete with women on wages and balancing out the wage disparity.[12] One study[13] found that customers who viewed videos featuring a black male, a white female, or a white male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19% more satisfied with the white male employee's performance and also were more satisfied with the store's cleanliness and appearance. This despite that all three actors performed identically, read the same script, and were in exactly the same location with identical camera angles and lighting. Moreover, 45 percent of the customers were women and 41 percent were non-white, indicating that even women and minority customers prefer white men. In a second study, they found that white male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally-well performing women or minority doctors. They interpret their findings to suggest that employers are willing to pay more for white male employees because employers are customer driven and customers are happier with white male employees. They also suggest that what is required to solve the problem of wage inequality isn't necessarily paying women more but changing customer biases. This paper has been featured in many media outlets including The New York Times,[14] The Washington Post,[15]The Boston Globe,[16] and National Public Radio.[17] However, the Independent Women's Forum cites another study that found that the wage gap nearly disappears "when controlled for experience, education, and number of years on the job."[18]

Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Main articles: Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964Legislation passed by the Federal Government of the United States in 1963 made it illegal to pay men and women different wage rates for equal work on jobs that require equal skill, effort, and responsibility and are performed under similar working conditions.[19] One year after passing the Equal Pay Act, Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Title VII of this act, makes it unlawful to discriminate based on a person’s race, religion, color, or sex.[20] Title VII attacks sex discrimination more broadly than the Equal Pay Act extending not only to wages but to compensation, terms, conditions or privileges of employment. Thus with the Equal Pay Act and Title VII, an employer cannot deny women equal pay for equal work; deny women transfers, promotions, or wage increases; manipulate job evaluations to relegate women’s pay; or intentionally segregate men and women into jobs according to their gender.[21]

Since Congress was debating this bill at the same time that the Equal Pay Act was coming into effect, there was concern over how these two laws would interact, which led to the passage of Senator Bennett’s Amendment. This Amendment states: “It Shall not be unlawful employment practice under this subchapter for any employer to differentiate upon the basis of sex . . . if such differentiation is authorized by the provisions of the [Equal Pay Act].” There was confusion on the interpretation of this Amendment, which was left to the courts to resolve.[22]

Washington and Minnesota State Actions

In Washington, Governor Evans implemented a pay equity study in 1973 and then another in 1977.[23] The results clearly showed that when comparing male and female dominated jobs there was almost no overlap between the averages for similar jobs and in every sector, a twenty percent gap emerged. For example, a food service worker earned $472 per month, and a Delivery Truck Driver earned $792, though they were both given the same amount of “points” on the scale of comparable worth to the state.[24] Unfortunately for the state, and for the female state workers, his successor Governor Dixie Lee Ray failed to implement the recommendations of the study (which clearly stated women made 20 percent less than men).[25] Thus in 1981, AFSCME filed a sex discrimination complaint with the EEOC against the State of Washington. The District Court ruled that since the state had done a study of sex discrimination in the state, found that there was severe disparities in wages, and had not done anything to ameliorate these disparities, this constituted discrimination under Title VII that was “pervasive and intentional.”[26] The Court then ordered the State to pay its over 15,500 women back pay from 1979 based on a 1983 study of comparable worth.[27] This amounted to over $800 million dollars. However, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit overturned this decision, stating that Washington had always required their employees’ salaries to reflect the free market, and discrimination was one cause of many for wage disparities. The court stated, “the State did not create the market disparity . . . [and] neither law nor logic deems the free market system a suspect enterprise.”[28] While the suit was ultimately unsuccessful, it led to state legislation bolstering state workers’ pay. The costs for implementing this equal pay policy was 2.6% of personnel costs for the state.[29]

In Minnesota, the state began considering a formal comparable worth policy in the late 1970s when the Minnesota Task Force of the Council on the Economic Status of Women commissioned Hay Associates to conduct a study. The results were staggering and similar to the results in Washington (there was a 20% gap between state male and female workers pay). Hay Associates proved that in the 19 years since the Equal Pay Act was passed, wage discrimination persisted and had even increased over from 1976 to 1981.[30] Using their point system, they noted that while delivery van drivers and clerk typists were both scaled with 117 points each of “worth” to the state, the delivery van driver (a male dominated profession) was paid $1,382 a month while the clerk typist (a female dominated profession) was paid $1,115 a month.[31] The study also noted that women were severely underrepresented in manager and professional positions; and that state jobs were often segregated by sex. The study finally recommended that the state take several courses of action: 1) establish comparable worth considerations for female- dominated jobs; 2) set aside money to ameliorate the pay inequity; 3) encourage affirmative action for women and other minorities and 4) continue analyzing the situation to improve it. The Minnesota Legislature moved immediately in response. In 1983 the state appropriated 21.8 million dollars to begin amending the pay disparities for state employees.[32] From 1982 to 1993, women’s wages in the state increased 10%. According to the Star Tribune, in 2005 women in Minnesota state government made 97 cents to the dollar, ranking Minnesota as one of the most equal for female state workers in the country.

Different Studies and Economic Theories

Economists expect that in free market capitalist economy managers should be eager to hire less costly women workers, thereby making the wage gap disappear.[33] Therefore economists are puzzled why the wage gap persists. One study[34] found that customers who viewed videos featuring a black male, a white female, or a white male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19% more satisfied with the white male employee's performance and also were more satisfied with the store's cleanliness and appearance. This despite that all three actors performed identically, read the same script, and were in exactly the same location with identical camera angles and lighting. Moreover, 45 percent of the customers were women and 41 percent were non-white, indicating that even women and minority customers prefer white men. In a second study, they found that white male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally-well performing women or minority doctors. They interpret their findings to suggest that employers are willing to pay more for white male employees because employers are customer driven and customers are happier with white male employees. They also suggest that what is required to solve the problem of wage inequality isn't necessarily paying women more but changing customer biases. This paper has been featured in many media outlets including The New York Times,[35] The Washington Post,[15]The Boston Globe,[16] and National Public Radio.[17] However, the Independent Women's Forum cites another study that found that the wage gap nearly disappears "when controlled for experience, education, and number of years on the job."[18]

Possibility of a reversal

The momentum of the change has been dramatic with the most recent generations. However, a closer look at the figures shows that — at present — the United States is still in the linear region of the transition, with little sign of a slowdown yet. Therefore, the possibility arises that there may actually be a reversal in the coming decades, with women outearning men in the aggregate.

This is the most important aspect of the overall picture missed by the two prevailing points of view. While the discussion continues on why the inequity "still exist", the most recent changes in the world are blindsiding all involved.

A dramatic picture of this change—particularly how it is being masked under the weight of the baby boomer generation and older world—is seen in the TV news sector. An aggregate comparison of women's and men's salaries for TV news anchors shows that women are making 38% less than men overall (as of 2000), yet women are outearning men at each age range.

Age Group 20-29 30-39 40-up Comparison +10% +15% +14% This is an example of Simpson's paradox. The complete disconnect between aggregate and age-related figures is actually somewhat predictable as a consequence of the gender shift that has taken place in this field. The vast majority of graduates from Communications schools in the United States are now female. Yet, there is still a significant vestige from the older, male-dominated, era—particularly at the highest positions in the field. The net result is not only a gap in the average ages (29 for females, 38 for males) but, with the influx of women from the colleges, a widening in the age gap, and very likely the aggregate wage gap, itself!

This widening is, therefore, actually a precursor of a forthcoming reversal in the direction of movement, rather than a sign of a worsening situation.

The time inevitably comes when the older generations must leave the field—whether by the attrition of retirement or death. In the national TV news arena, this has already started to happen. With the departure of the older cohort, the masking effect of the pulling down of the average by the baby boomers' and earlier generations will be removed, resulting in what will appear to be a sudden upswing in the aggregate wage gap and even a reversal.[36]

See also

- Allonby v. Accrington and Rossendale College

- Bennett Amendment

- Glass ceiling

- Material feminism

- Paycheck Fairness Act (in the US)

- Gender pay gap

- Male–female income disparity in the United States

- Gender pay gap in Australia

References

- ^ a b European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on August 27, 2011.

- ^ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook - 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3-4.

- ^ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- ^ Chubb, Catherine, Simone Melis, Louisa Potter, and Raymond Storry. The Global Gender Pay Gap, International Trade Union Confederation, February 2008.

- ^ ITUC. Gender Pay Gap Stuck at 16% Worldwide: New ITUC Report, accessed on August 27, 2011.

- ^ Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/women.html

- ^ Coorey, Phillip (10 November 2011). "Gillard's $2bn equal pay push to see lowest-paid workers' salaries soar". Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/national/gillards-2bn-equal-pay-push-to-see-lowestpaid-workers-salaries-soar-20111110-1n8jh.html. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Canadian Human Rights Commission, http://www.chrc-ccdp.ca

- ^ a b Ontario Ministry of Labour - Employment Standards, http://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/es/

- ^ Ontario Pay Equity Commission, http://www.payequity.gov.on.ca

- ^ "C350". iwpr.org. http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-gender-wage-gap-2009.

- ^ "Are Women Earning More Than Men?". Forbes.com. May 12, 2006. http://www.forbes.com/ceonetwork/2006/05/12/women-wage-gap-cx_wf_0512earningmore.html.

- ^ Hekman, David R.; Aquino, Karl; Owens, Brad P.; Mitchell, Terence R.; Schilpzand, Pauline; Leavitt, Keith. (2009) An Examination of Whether and How Racial and Gender Biases Influence Customer Satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2009) “A Customer Bias in Favor of White Men.” New York Times. June 23, 2009, page D6

- ^ a b Vedantam, Shankar (2009) “Caveat for Employers.” Washington Post, June 1, 2009, page A8

- ^ a b Jackson, Derrick (2009) “Subtle, and stubborn, race bias.” Boston Globe, July 6, 2009, page A10

- ^ a b National Public Radio, Lake Effect

- ^ a b Gender Wage Gap Is Feminist Fiction by Arrah Nielsen, Independent Women's Forum, April 15, 2005

- ^ Equal Pay Act of 1963, finduslaw.com

- ^ “Civil Rights Act of 1964.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2000e-17

- ^ Williams, Robert et al. Closer Look at Comparable Worth: A Study of the Basic Questions to be Addressed in Approaching Pay Equity. National Foundation for the Study of Equal Employment Policy: Washington, DC, 1984, pg. 28.

- ^ Webber, Katie. “Comparable Worth—It’s Present Status and the Problem of Measurement.” Hamline Journal of Public Law, Vol. 6, No. 38 (1985), pg. 37.

- ^ Remick, Helen. “ ‘A Want of Harmony’: Perspectives on Wage Discrimination and Comparable Worth.” Ed. Remick, Helen. Comparable Worth and Wage Discrimination: Technical Possibilities and Political Realities. Temple University Press: Philadelphia, 1984, 102.

- ^ Steinberg, Ronnie. “ ‘A Want of Harmony’: Perspectives on Wage Discrimination and Comparable Worth.” Ed. Remick, Helen. Comparable Worth and Wage Discrimination: Technical Possibilities and Political Realities. Temple University Press: Philadelphia, 1984, pg. 102.

- ^ Stewart, Debra A. “State Initiatives in the Federal System: The Politics and Policy of Comparable Worth in 1984.” Publius, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 1985), pg. 84.

- ^ American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO (AFSCME), et al. v. State of Washington et al. No. C 82-465T (District Court for the Western District of Washington), 1983.

- ^ Legler, Joel Ivan. “City, County and State Government Liability for Sex-Based Wage Discrimination After County of Washington v. Gunther and AFSCME v. Washington.” The Urban Lawyer, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Spring 1985), pg. 241.

- ^ American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO (AFSCME), et al. v. State of Washington et al. 770 F.2d 1401 (9th Cir), 1985.

- ^ “National Committee on Pay Equity,” pay-equity.org, Accessed Nov. 8, 2010

- ^ Cook, Alice H. Comparable Worth: A Case book of experiences in states and localities. Industrial Relations Center: University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1985, pg. 141

- ^ “Pay Equity: The Minnesota Experience: Fifth Edition.” Legislative Commission on the Economic Status of Women, April 1994, pg. 13.

- ^ Stewart, Debra A. “State Initiatives in the Federal System: The Politics and Policy of Comparable Worth in 1984.” Publius, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 1985), pg. 91.

- ^ "Are Women Earning More Than Men?". Forbes.com. May 12, 2006. http://www.forbes.com/ceonetwork/2006/05/12/women-wage-gap-cx_wf_0512earningmore.html.

- ^ Hekman, David R.; Aquino, Karl; Owens, Brad P.; Mitchell, Terence R.; Schilpzand, Pauline; Leavitt, Keith. (2009) An Examination of Whether and How Racial and Gender Biases Influence Customer Satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal.

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2009) “A Customer Bias in Favor of White Men.” New York Times. June 23, 2009, page D6.

- ^ Gender Gaps and Factors in Television News Salaries, Vernon Stone

External links

- Pay Equity Survey

- CNN report

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Pay Equity

- "Whatever Happened to Equal Pay?" Marxist Essay

- Pay Equity Group

- "Is The Wage Gap Women's Choice", Rachel Bondi

- "The Truth Behind Women's Wages in Mining", Jack Caldwell and Cecilia Jamasmie

Categories:- Public economics

- Employment compensation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.