- German school of fencing

-

German School of Fencing

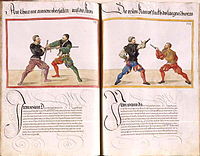

page of Mscr. Dresd. C 93 by Paulus Hector Mair (1540s)Also known as Deutsche Fechtschule, German Swordsmanship, Kunst des Fechtens Focus longsword, messer, dagger, polearms, grappling Country of origin  Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman EmpireFamous practitioners Johannes Liechtenauer, Paulus Hector Mair, Sigmund Ringeck Olympic sport No The German school of fencing (Deutsche Fechtschule) is the historical system of combat taught in the Holy Roman Empire in the Late Medieval, Renaissance and Early Modern periods (14th to 17th centuries), as described in the Fechtbücher ("fight books") written at the time. During the period in which it was taught, it was known as the Kunst des Fechtens, or the "Art of Combat".[1] It notably comprises the techniques of the two-handed Zweihänder (two hander), but also describes many other types of combat, notably mounted combat, unarmed grappling, fighting with polearms, with the dagger, the messer with or without buckler, and the staff.

Most of the authors are, or claim to be, in the tradition of the 14th century master Johannes Liechtenauer. The earliest surviving treatise on Liechtenauer's system is contained in a manuscript dated to 1389, known as Ms. 3227a. More manuscript treatises survive from the 15th century, and during the 16th century, the system was also presented in print, notably by Joachim Meyer in 1570. The German tradition is eclipsed by the Italian school of rapier fencing by the early 17th century.

Fencing with the German longsword has been one focus of historical martial arts reconstruction since the late 20th century.

Contents

History

The history of the German school spans roughly 250 years, or eight to ten generations of masters (depending on the dating of Liechtenauer), from 1350 to 1600. Our earliest source, Ms. 3227a of 1389 already mentions a number of masters, considered peers of Liechtenauer's, Hanko Döbringer, Andres Jud, Jost von der Nyssen, and Niklaus Preuss. Probably active in the early 15th century were Martin Hundsfeld and Ott Jud, but sources are sparse until the mid 15th century.

The mid 15th century mark the peak and decline of the "Society of Liechtenauer" with Peter von Danzig, Sigmund Ringeck and Paulus Kal. Kal's contemporary Hans Talhoffer was possibly involved with the foundation of the Brotherhood of St. Mark who enjoyed a quasi-monopoly on teaching martial arts for the best part of a century, from 1487 until 1570.

Late 15th centuries masters include Johannes Lecküchner, Hans von Speyer, Peter Falkner, and Hans Folz. With the 16th century, the school becomes more of a sport and less of a martial art designed for judicial duels or the battlefield. Early 16th century masters include Hans Wurm and Jörg Wilhalm.

In the mid 16th century, there were first attempts at preservation and reconstruction of the teachings of the past century, notably by Paulus Hector Mair. The foundation of the Federfechter in 1570 at Vienna falls into this late period. The final phase of the tradition stretches from the late 16th to the early 17th century, with masters such as Joachim Meyer and Jakob Sutor. In the 17th century, rapier fencing of the Italian school becomes fashionable, with treatises such as Salvator Fabris', and the German tradition, falling into disfavour as old-fashioned and unrefined among the baroque nobility, was discontinued.

Disciplines

Master Johannes Liechtenauer based his system of fencing upon the use of the Longsword. He used this weapon to exemplify several overarching martial principles that also apply to other disciplines within the tradition. Ringen (wrestling/grappling) was taught, as well as fighting with the messer, and staff. Also part of the curriculum were fighting with the dagger Degen (mainly the roundel dagger) and with pole weapons. Two other disciplines besides Blossfechten involved the sword: fencing with (single-handed) sword and buckler (or a large shield in the case of judicial combat according to Swabian law), and armoured fighting (Harnischfechten), the latter reserved for nobility.

First principles

Johannes Liechtenauer's teachings as recorded in 3227a are introduced by some general principles (foll. 13-17). The anonymous author explicitly states that Liechtenauer had cast his teaching in opaque verses intended to hide their meaning from the unitiated. He stresses that there is "only a single art of the sword" which had been the same for centuries, and which is the kernel and foundation of all arts of combat.

- the principle of taking the shortest and most direct line of attack (of das aller neheste vnd kors körtzste / slecht vnd gerade czu) disregarding flourishes or flashy parrying techniques ( mit dem höbschen paryrn vnd weit vmefechten).

- the difficulty of explaining techniques in words, and the importance of direct instruction and intensive training, offering the aphorism that "exercise is better than art, because exercise without art is useful, but art without exercise is useless" (15r).

- the importance of footwork and stance (15v) and of correct distance (mosse, 15v) and speed of motion (16r)

- the importance of taking the offensive (vorslag, 14v, 16r-16v), with a fixed plan of attack

- the tactical importance of hiding the intended action from the opponent (16r)

The text goes on to present the core principles of successful swordsmanship in eight rhyming couplets (17v):

1. the help of God Czu allem fechten / gehört dy hölfe gotes von rechte 2. a healthy body and a good weapon Gerader leip vnd gesvnder / eyn gancz vertik swert pesundr 3. the principles of offensive and defensive and of hard and soft Vor noch swach sterke / yndes das wort mete czu merken 4.-5. a list of basic techniques (discussed below) Hewe stiche snete drücken / leger schütczen stöße fülen czücken

Winden vnd hengen / rücken striche sprönge greiffen ringen6. speed and courage paired with wariness, deceit and cleverness Rascheit vnd kunheit / vorsichtikeit list vnd klugheit 7. correct distance, concealing one's intentions, reason, anticipation and dexterity Masse vörborgenheit / vernunft vorbetrachtunge fertikeit 8. training and confidence, speed, agility and good footwork Vbunge vnd guter mut / motus gelenkheit schrete gut A characteristic introductory verse of Liechtenauer's, often repeated in later manuscripts, echoes classic 14th-century chivalry, addressing the student as "young knight" (jung ritter), notwithstanding that during most of its lifetime, the German school was very much in bourgeois hands:

- (fol 18r) Jung Ritter lere / got lip haben frawen io ere / So wechst dein ere / Uebe ritterschaft und lere / kunst dy dich zyret und in krigen sere hofiret

- "Young knight, learn to love God and revere noble ladies, so that your honour grows. Practice knighthood and learn the art that dignifies you, and brings you honour in wars."

Unarmoured longsword

The principal discipline is unarmoured fencing with the longsword (Blossfechten).

At the basis of the system are five 'master-hews' (Meisterhäue) or 'hidden hews' from which many masterful techniques arise, twelve 'chief pieces' ("hauptstücke") that categorize the main components of the art, and five words (fünf Wörter) dealing with concepts of timing and leverage.

At the centre of the art lies emphasis on swiftness, as well as balance and good judgement:

- (fol. 20r) vor noch swach stark Indes / an den selben woertern leit alle kunst / meister lichtnawers / Und sint dy gruntfeste und der / kern alles fechtens czu fusse ader czu rosse / blos ader in harnuesche

- "'Before', 'after', 'weak', 'strong', Indes ('meanwhile'), on these five words hinges the entire art of master Lichtenauer, and they are the foundation and the core of all combat, on foot or on horseback, unarmoured or armoured."

The terms 'before' (vor) and 'after' (nach) correspond to offensive and defensive actions. While in the vor, one dictates his opponent's actions and thus is in control of the engagement, while in the nach, one responds to the decisions made by his opponent. Under Liechtenauer's system, a combatant must always strive to be in control of the engagement—that is, in the vor. 'Strong' (stark) and 'weak' (swach) relate to the amount of force that is applied in a bind of the swords. Here, neither is better than the other, but one needs to counter the opponent's action with a complementary reaction; strength is countered with weakness, and weakness with strength. Indes means "meanwhile" or "interim", referring to the time it takes for the opponent to complete an action. At the instant of contact with the opponent's blade, an experienced fencer uses 'feeling' (fühlen) to immediately sense his opponent's pressure in order to know whether he should be "weak or "strong" against him. He then either attacks using the "vor" or remains in the bind until his opponent acts, depending on what he feels is right. When his opponent starts to act, the fencer acts "indes" (meanwhile) and regains the "vor" before the opponent can finish his action.[2]

-

pflug and ochs, as shown on fol. 1r of Cod. 44 A 8 (1452)

What follows is a list of technical terms of the system (with rough translation; they should each be explained in a separate section):

Basic Attacks

Liechtenauer and other German masters describe three basic methods of attack with the sword. They are sometimes called "drei wunder", "three wounders", with a deliberate pun on "three wonders".

- Hauen, "hews": A hewing stroke with one of the edges of the sword.

- Oberhau, "over hew": A stroke delivered from above the attacker.

- Mittelhau, "middle hew": A stroke delivered from side to side.

- Unterhau, "under hew": A stroke delivered from below the attacker.

- Stechen, "stabbing": A thrusting attack made with the point of the sword.

- Abschneiden, "slicing off": Slicing attacks made with the edge of the sword by placing the edge against the body of the opponent and then pushing or pulling the blade along it.

Master-Hews

Called "five hews" in 3227a, later "hidden hews", and in late manuals "master hews". These likely originated as secret surprise attacks in Liechtenauer's system, but with the success of Liechtenauer's school, they may have become common knowledge. All five are attacks from the first phase of the fight (zufechten) and long range, accompanied by triangular stepping.

- Zornhau: 'wrath-hew'

- A powerful diagonal hewing stroke dealt from the vom Tag guard that ends in the Wechsel guard on the opposite side.[3] When a Zornhau is used to displace (Versetzen) another oberhau the impact and binding of the blades will result in the hew ending in a lower hanging at the center of the body.[4] This strike is normally thrown to the opponent's upper opening.

- Krumphau: 'crooked-hew'

- A vertical hew from above that reaches across the direct line to the opponent, traveling left from a right position and vice versa. The motion of the blade resembles a windshield wiper. Krumphau is almost always accompanied with a wide diagonal sideways step. The Krumphau breaks the guard Ochs.

- Zwerchhau: or Twerhau 'thwart-hew'

- A high horizontal hew, with the 'short' (backhand) edge when thrown from the right side and with the 'long' edge when thrown from the left side. The Zwerchau breaks the guard vom Tag.

- Schielhau: 'squinting-hew'

- A short edge (backand) hew dealt from the vom Tag guard that ends in an upper hanger on the opposite side and usually targets the head or the right shoulder.[4] It is basically a twist from vom Tag to opposite side Ochs with one step forward, striking simultaneously downwards with short edge. The Schielhau breaks the both the Pflug and Langen Ort guards and can be used to counter-hew against a powerful Oberhau.

- Scheitelhau: 'part-hew'

- A vertical descending hew that ends in the guard Alber. This hew is dealt to the opponent's upper openings, most often to the opponent's head, where the hair parts (hence the name of the hew). Through the principle of überlauffen, “overrunning” or “overreaching”, a Scheitelhau is used to break the guard Alber.[4]

Guards

Basic Guards

- vom Tag: 'from-roof'

- a basic position with the sword held either on the right shoulder or above the head. The blade can be held vertically or at roughly 45-degrees.[5]

- Ochs: 'ox'

- a position with the sword held to either side of the head, with the point (as a horn) aiming at the opponent's face.

- Pflug: 'plough'

- a position with the sword held to either side of the body with the pommel near the back hip, with the point aiming at the opponent's chest or face. Some historical manuals state that when this guard is held on the right side of the body that the short edge should be facing up and when held on the left side of the body the short edge should be facing down with the thumb on the flat of the blade.[6]

- Alber: 'fool'

- In the Fool's Guard, the point of the sword is lowered to the ground, appearing to "foolishly" expose the upper parts of the body and inviting an attack. Although the Fool's Guard exposes the upper openings it does provide excellent protection to the lower openings. From the Fool's Guard an attack or displacement can be made with the false edge of the sword or the hilt of the sword can be quickly raised into a hanging parry.

Additional Guards: Liechtenauer is emphatic that the above four guards are sufficient, and all guards taught by other masters may be derived from them. Later masters introduce richer terminology for variant guards:

- Zornhut: 'wrath guard'

- Langort: 'long point', the sword point is extended straight out at the opponent, presenting a barrier of distance to the opponent while threatening him with the tip

- Wechsel: 'change'

- Nebenhut: 'near guard' or 'side guard'

- Eisenport: 'iron door', mentioned in 3227a as a non-Liechtenauerian ward, identical to the porta di ferro of the Italian school

- Schlüssel: 'key'

- Einhorn: 'unicorn', a variant of Ochs

- Schrankhut: 'barrier guard'

The following are transitional stances that are not properly called guards.

- Hengetort: 'hanging point'

- Kron: 'crown', the sword is held with the hilt close to the head, point up. Used at the bind and is usually a prelude to grappling.

Techniques

Other terms in Liechtenauers system (most of them referring to positions or actions applicable in mid-combat, when the blades are in contact) include:

- Duplieren: 'doubling', the immediate redoubling of a displaced hew.

- Mutieren: 'mutating', change of attack method, changing a displaced hew into a thrust, or a displaced thrust into a hew.

- Versetzen: 'displacement' or 'parrying'[2] (upper/lower, left/right), to parry an attack with ones own weapon.

- Nachreisen: 'after-traveling', the act of attacking an opponent after he has pulled back to attack, or an attack after the opponent has missed, or an attack following the opponent's action.[2]

- Überlaufen: 'over-running' or 'overrunning', the act of countering a hew or thrust made to below with an attack to above.

- Absetzen: 'off-setting', deflecting a thrust or hew at the same time as stabbing.

- Durchwechseln: 'changing-through', name for various techniques for escaping a bind by sliding the sword's point out from underneath the blade and then stabbing to another opening.

- Zucken: 'tugging' a technique used in a strong bind between blades in which a combatant goes weak in the bind so as to disengage his blade from the bind and stabs or hews to the other side of the other combatant's blade. This technique is based upon the concept of using weakness against strength.

- Durchlauffen: 'running-through', a technique by which one combatant "runs through" his opponent's attack to initiate grappling with him.

- Händedrücken: 'pressing of hands', the execution of an Unterschnitt followed by an Oberschnitt such that the wrists of the opponent are sliced all the way around.

- Hängen: 'hanging' (upper/lower, left/right)

- Winden: 'Winding' The combatant moves the strong of his blade to the weak of the opponent's blade to gain leverage while keeping his point online with the opponent's opening. There are 8 variations.

Armoured combat

Halbschwert against Mordstreich in the Codex Wallerstein (Plate 214)

Halbschwert against Mordstreich in the Codex Wallerstein (Plate 214)

Combat in full plate armour made use of the same weapons as Blossfechten, the longsword and dagger (possibly in special make optimized for piercing the openings in armour), but the techniques were entirely different. Attacking an opponent in plate armour offers two basic possibilities: percussive force, or penetration at joints or unprotected areas. Penetration was extremely unlikely even with thrusting attacks. Percussion was realized with the Mordstreich, attacks with the hilt holding the sword at the blade, and penetration into openings of the armour with the Halbschwert, which allowed stabbing attacks with increased precision. From the evidence of the Fechtbücher, most armoured fights were concluded by wrestling moves, with one combatant falling to the ground. Lying on the ground, he could then be easily killed with a stab into his visor or another opening of the armour.

See also

- Historical European Martial Arts

- Italian school of fencing

- Kampfringen

Literature

- Clements, John. Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts: Rediscovering The Western Combat Heritage. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3

- Heim, Hans & Alex Kiermayer, The Longsword of Johannes Liechtenauer, Part I -DVD-, ISBN 1-891448-20-X

- Knight, David James and Brian Hunt, Polearms of Paulus Hector Mair , ISBN 978-1-58160-644-7 (2008)

- Lindholm, David & Peter Svard, Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword, ISBN 1-58160-410-6 (2003)'

- Schulze, André (ed.) , Mittelalterliche Kampfesweisen - Mainz am Rhein. : Zabern

- vol. 1: Das Lange Schwert, 2006. - ISBN 3-8053-3652-7

- vol. 2, Kriegshammer, Schild und Kolben, 2007. - ISBN 3-8053-3736-1

- vol. 3: Scheibendolch und Stechschild, 2007. - ISBN 978-3-8053-3750-2

- Thomas, Michael G., Fighting Man's Guide to German Longsword Combat, ISBN 978-1-906512-00-2 (2008)

- Tobler, Christian Henry, Fighting with the German Longsword, ISBN 1-891448-24-2 (2004)

- Tobler, Christian Henry, Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship (2001), ISBN 1-891448-07-2'

- Tobler, Christian Henry, In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts (2010), ISBN 978-0-9825911-1-6

Notes

- ^ The Early Modern German fechten translates to the English etymological equivalent, to fight. In Modern German, fechten has come to mean "fencing", but translating fechten as "fencing" in a pre-16th century context is an anachronism; the English verb "to fence" in the sense of "fighting with swords" arises in the 1590s, in Shakespeare, in reference specifically to the Elizabethan Art of Defence.

- ^ a b c Abnemen

- ^ A Zornhau may be thrown from another guard, such as Ochs, but in doing so the person will move through the vom Tag guard.

- ^ a b c The Mastercuts – What They Are and What They Aren’t by Bartholomew Walczak and Jacob Norwood.

- ^ The Basic Guards of Medieval Longsword by John Clements - note the depictions of vom Tag.

- ^ The Basic Guards of Medieval Longsword by John Clements.

External links

- The Wiktenauer The world's largest database of historical German fighting manuals

- Call to Arms: The German Longsword by Bill Grandy

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.