- Maria Valtorta

-

This article is about Maria Valtorta's life. For her major literary work, please see The Poem of the Man God.

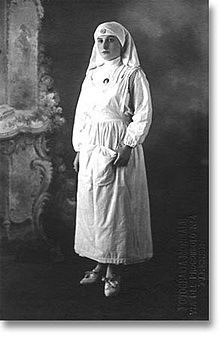

At age 21, in the uniform of a Samaritan Nurse, 1918.

At age 21, in the uniform of a Samaritan Nurse, 1918.

Maria Valtorta (14 March 1897 – 12 October 1961) was a Roman Catholic Italian writer and poet, considered by many to be a mystic. Her work centers on Catholic Christian themes. Her followers believe that she had personally conversed with Jesus Christ in her visions of Jesus and Mary[1]

Contents

Early life

Valtorta was born in Caserta, in the Campania region of Italy, the only child of parents from the Lombardy region. Her father, Giuseppe, was in the Italian cavalry and her mother, Iside, was a French teacher.[2]

At age 7 she was enrolled in the Institute of the Marcellienne Sisters and at age 12 she was sent to boarding school. As the family moved around Italy due to her father's military career, she received a classic education in various parts of Italy and focused on Italian literature. In 1917 she entered the ranks of the Samaritan Nurses and for 18 months offered her service at the military hospital in Florence.

On 17 March 1920, at the age of 23, while she was walking on a street with her mother, a delinquent youth struck her in the back with an iron bar for no apparent reason. She was confined to bed for three months. Although she seemed to have recovered after three months, and was able to move around for over a decade thereafter, the complications from that injury eventually confined her to bed for 28 years, from 1934 onwards.[3]

Settling in Viareggio

In 1924, her father retired and the family settled in the town of Viareggio, on the coast of Tuscany in 1924.[4] After settling in Viareggio (which means "way of the kings"), she hardly ever left that town. In Viareggio Maria led a life dominated by solitude. Except for occasional excursions to the seaside and the pine-forest, her days mostly consisted of doing the daily household shopping and visiting the Church for the Blessed Sacrament.

In 1925 she read the autobiography of St. Theresa of the Child Jesus at one sitting. The experience was deeply moving to her and on January 28, 1925 she offered herself as victim to the merciful Love. In December 1929, she was admitted to Catholic Action as youth cultural delegate, and in 1930 took private vows of chastity, poverty and obedience.

January 4, 1933 was the last day on which Maria, walking with extraordinary fatigue, was able to leave her house. And from 1 April 1934, she was no longer able to leave her bed. In 1935, a year after she was bed-ridden, Martha Diciotti began to care for her.

In 1942 she was visited by a missionary priest, Fr. Rornuald M. Migliorini of the Servants of Mary, who became her spiritual director for four years. In 1943 her mother died and Martha Diciotti became her only constant companion and listener until her death. Except for a brief wartime evacuation to Sant’ Andrea di Compito in Lucca, from April to December 1944 during the Second World War, the rest of her life was spent in her bed at 257 Via Antonio Fratti in Viareggio.

Report of Visions

Early in 1943, when Maria had been infirm for nine years, her religious advisor, Father Migliorini, suggested to her to write about her life. After some hesitation, she agreed and, in about two months had produced several hundred handwritten pages for her confessor.

On the morning of Good Friday April 23, 1943, she reported a sudden voice speaking to her and asking her to write. From her bedroom Maria called for Marta Diciotti, showed her the sheet in her hands and said that something extraordinary had happened. Marta called Father Migliorini regarding the dictation Maria had reported and he arrived soon thereafter. Father Migliorini asked her to write down anything else she received and over time provided her with notebooks to write in.

Thereafter, Maria wrote almost every day until 1947 and intermittently in the following years until 1951. She would write with a fountain pen in the notebook resting on her knees and placed upon the writing board she had made herself. She did not prepare outlines, did not even know what she would write from one day to another, and did not reread to correct. At times she would call Marta to read back to her what she had written.[5]

One of Maria's declarations reads:

- "I can affirm that I have had no human source to be able to know what I write, and what, even while writing, I often do not understand."

Her notebooks were dated each day, but her writing was not in sequence, in that some of the last chapters of The Poem of the Man God were written before the early chapters, yet the text flows smoothly between them.[6]

Notebooks

Main article: Poem of the Man GodFrom 1943 to 1951 Valtorta produced over 15,000 handwritten pages in 122 notebooks. She wrote her autobiography in 7 additional notebooks. These pages became the basis of her major work, The Poem of the Man God, and constitute about two thirds of her literary work. The visions give a detailed account of the life of Jesus from his birth to the Passion with more elaboration than the Gospels provide. For instance, while the Gospel includes a few sentences about the wedding at Cana, the text includes a few pages and narrates the words spoken among the people present. The visions also describe the many journeys of Jesus throughout the Holy Land, and his conversations with people such as the apostles.[7]

The handwritten pages were characterized by the fact that they included no overwrites, corrections or revisions and seemed somewhat like dictations. The fact that she often suffered from heart and lung ailments during the period of the visions made the natural flow of the text even more unusual. Readers are often struck by the fact that the sentences attributed to Jesus in the visions have a distinct and recognizable tone and style that is distinct from the rest of the text. Given that she never left Italy and was bed-ridden much of her life, Maria's writings reflect a surprising knowledge of the Holy Land. A geologist, Vittorio Tredici, stated that her detailed knowledge of the topographic, geological and mineralogical aspects of Palestine seems unexplainable. And a biblical archeologist, Father Dreyfus, noted that her work includes the names of several small towns which are absent from the Old and New Testaments and are only known to a few experts.[6] [8][9]

Popes Pius XII and John XXIII

Maria Valtorta was at first reluctant to have her notebooks published, but on the advice of her priest agreed in 1947 to their publication.

Her priest, Father Romualdo Migliorini and Father Corrado Berti, along with their Prior, Father Andrea Checchin, used their contacts to present the manuscript directly to Pope Pius XII. Among those impressed by the work at the Vatican was the Pope's confessor, Father (later Cardinal) Augustin Bea who later wrote that he found the work "not only interesting and pleasing, but truly edifying".[10] Father Berti presented the first copy of the work to Pius XII shortly after April 1947 and on 26 February 1948 received the three priests in audience,[11] and the papal audience was listed on the next day's L'Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper.

At the meeting Pope Pius XII reportedly told the three priests; "Publish this work as it is. There is no need to give an opinion about its origin, whether it be extraordinary or not. Who reads it, will understand. One hears of many visions and revelations. I will not say they are all authentic; but there are some of which it could be said that they are"[11] Father Berti then signed an affidavit to that effect, as did the other two witnesses, with written testimony.[12] The three priests understood this permission to publish as a papal imprimatur.[13][14]

The permission of the author's ordinary or of the ordinary of the place of publication or of printing was required for publishing such books, and that had to be given in writing. [15][16] Because Pope Pius XII had thus agreed, before the three priests of the Servite Order, to publication of the Poem of the Man God, it was offered for publication in 1948 to the Vatican Printing Office, which however did not publish it.

While Pius XII was alive, the Holy Office did not announce an official position on the manuscript. When Pius XII died in 1958, his newly appointed successor Pope John XXIII, upon taking office, signed in 1959 a decision by the Holy Office (then headed by Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani) to place the book on the Index of Forbidden Books, along with a number of other works, such as those of Sister Faustina Kowalska who was later declared a saint, and whose writings are now quoted by the Vatican.[17][18]

In 1987, Vatican Cardinal Edouard Gagnon was persuaded to locate and evaluate the original minutes from the February 26, 1948 Papal meeting transcribed by the Vatican Recording Cardinal who accompanied Pope Pius XII. Shortly afterwards Cardinal Gagnon wrote from the Vatican, that Pope Pius XII's action was "the kind of official Imprimatur granted before witnesses by the Holy Father in 1948, an Official Imprimatur of the Supreme Authority of the Church". The Cardinal Gagnon letter was eventually published in a 1992 CEV periodical.[19][20][21]

Cardinal Edouard Gagnon served as the Peritus (Expert Theologian Advisor and Consultant) during the second Vatican Council. He had a Doctorate in Theology and taught Canon law for ten years at the Grand Seminary.[22]

Controversy

Supporters of Maria Valtorta argue that, according to canon law, the Roman Pontiff has full power over the whole Church, hence the initial approval given by Pope Pius XII effectively nullified any subsequent ruling by the Holy Office. The detractors argue that the same canon law applied to Pope John XXIII when he signed the order to place the work on the Index. However, in 1963 Pope Paul VI succeeded John XXIII and abolished the Index altogether in 1965. Valtorta followers argue that this in effect nullified the suppression of 1959 since the Index no longer existed after 1965. Those opposed to the book considered the abolition of the Index as not reversing the Church's opinion of the work. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) while acting as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1985 wrote that "the Index retains its moral force despite its dissolution."[23] Valtorta supporters point to the fact that the long list of books on the Forbidden Index also included writings by Jean-Paul Sartre, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, John Milton, John Locke, Galileo Galilei, Blaise Pascal and Saint Faustina Kowalska, among others. But some authors (e.g. Karl Marx or Adolf Hitler) whose views are generally considered highly unacceptable to the Church were never put on the Index.[24][25][26]

At the moment the official position of the Catholic Church with respect to the book is less than clear. The Catholic Church does not endorse the book, yet does not ban it either, although church officials have made occasional comments about it. The last formal action taken by the Vatican with respect to the book was in 1992, when Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanzi, the Secretary General of the Italian Bishops' Conference, wrote to the publisher Emilio Pisani. In his letter, Tettamanzi requested that a paragraph be added to the first few pages of the book disclaiming any supernatural origin for the work. The publisher assumes that the letter indicates that the Italian Bishops' Conference sees nothing in the work that contradicts the doctrines of the Church, yet some detractors claim that the letter intended to classify the work as fiction. Since 1993 the Catholic Church has chosen to remain silent on its position with respect to the work.

The Poem of the Man God was eventually published as a 4,000 page multi-volume book and has since been translated into 10 languages and received the imprimatur and approval of several Catholic bishops and Cardinals worldwide. Valtorta's other literary works include historical notes on the early Catholic Church and martyrs and comments on biblical texts, as well as some religious poems and compositions.

The Poem of the Man God has, however, also drawn criticism from a variety of theologians and skeptics, who claim internal inconsistencies,[27] friction with the Holy See[28] and theological errors of the Biblical account of the Gospel and Catholic dogma.[29]

Regarding the issue of internal consistency and correspondence with the Gospels, Valtorta supporters point to the fact that ever since Saint Augustine of Hippo addressed the Augustinian hypothesis in the 5th Century, religious scholars have been debating issues regarding the comparison of various texts with the Gospels, at times with no clear resolution. Such debates still take place among experts even on issues regarding the Church Canons and the early Gospels themselves.[30][31] Valtorta supporters point to the fact that the Poem of the Man God seems to provide solutions to some synoptic debates such as those regarding Luke 22:66[32] and Matthew 26:57[33] on the Trial of Jesus by providing simple explanations that resolve the conflicts.[34] And highly respected scripture scholars such as the Venerable Gabriele Allegra have expressed their support for the Poem of the Man God and its correspondence with the Gospel.[35]

As for friction with and within the Holy See, it is well documented that the Cardinals favorable towards Valtorta's writings (e.g. Cardinal Augustin Bea) and those opposing it (e.g. Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani) had high levels of friction with each other on a wide range of issues beyond Valtorta's work.[36] Thus in defense of Maria Valtorta, when providing his imprimatur for the Poem of the Man God, Bishop Roman Danylak recalled John 8:7[37] and referred to some of her critics as "those who want to cast stones".[38]

Death and burial

Maria Valtorta died and was buried in Viareggio in 1961, at age 64. In 1973 with ecclesiastic permission, her remains were moved to Florence to the Chapel in the Grand Cloister of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata di Firenze. Chiseled on her tomb are the words: "DIVINARUM RERUM SCRIPTRIX" (Writer of Divine Things).

Presiding over the services at Valtorta's "privileged burial" and the relocation of her remains from Viareggio to the Santissima Annunziata Basilica was Father Gabriel M. Roschini.[39] A respected Mariologist, founding professor at the Marianum pontifical institute in Rome and advisor to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Father Roschini had studied Valtorta's writings and her book The Poem of the Man God and was initially skeptical of the authenticity of her work. But upon studying her work further he grew to appreciate it as a private revelation. He wrote of Valtorta's work:

- "We find ourselves facing an effect (her work) which seems to be beyond its cause (Maria Valtorta)".[40]

The house at 257 Via Antonio Fratti in Viareggio, where all her messages were written, was purchased by the publisher of The Poem of the Man God and has been preserved intact. It can be visited by appointment in Viareggio, Italy.

Mentions in other reported visions

In the 1980s, she was mentioned in the visions of two of the visionaries in Medjugorje. The Medjugorje visions by Marija Pavlovic and Vicka Ivankovic both stated that Maria Valtorta's records of her conversations with Jesus are truthful. According to Ivankovic, in 1981 the Virgin Mary told her at Medjugorje: "If a person wants to know Jesus he should read Maria Valtorta".[41][42][43][44][45] According to printed records of Medjugorje messages, Marija Pavlovic stated that she was told at Medjugorje by the Virgin Mary that it was permitted to read Maria Valtorta's book.[46][47]

A 2009 Yale University student report details the intricate connection between the Medjugorje apparitions and the writings of Maria Valtorta.[48][49]

Maria Valtorta's work is also mentioned in the writings of Archbishop Don Ottavio Michelini, from Mirandola, who reported a series of Dictations and Visions given to him by Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary from 1975 to 1979. He reported these words dictated to him by Christ:

I have dictated to Maria Valtorta, a victim soul, a marvelous work. Of this work I am the Author. You yourself, Son, have taken account of the raging reactions of Satan.... You have verified the resistance that many priests oppose to this work. This also proves, Son, that he who has not sensed in the Poem the savor of the Divine, the perfume of the Supernatural, has a soul encumbered and darkened. If it were -- I do not say "read" --but studied and meditated, it would bring an immense good to souls. This work is a well-spring of serious and solid culture.... This is a work willed by Wisdom and Divine Providence for the new times. It is a spring of living and pure water. It is I, the Word living and eternal, Who have given Myself anew as nourishment to the souls that I love. I, Myself, am the Light, and the Light cannot be confused with, and still less blend Itself with, the darkness. Where I am found, the darkness is dissolved to make room for the Light.

The particular Michelini book from which this quotation was taken is called La medida está colmada in its Spanish version and remains in the library of The Archidiocesan Minor Seminary of Monterrey in the city of San Pedro Garza García. It is worth noting that the first page of the book has a seal that reads "Biblioteca Seminario Menor de Monterrey Donativo del Sr. Emmo. Adolfo Antonio Cardenal Suárez Rivera", ("Library of the Minor Seminary of Monterrey Donated by Sr. Eminentísimo Adolfo Cardinal Suárez Rivera"). He was for many years Cardinal Archbishop of the Diocese of Monterrey. This Spanish edition of Michelini's writings where supposedly Christ himself defends Valtorta's Work, comes with a copy of two letters between Bishops (within the first pages). The first letter is from the Bishop of León, México Anselmo Zarza Bernal and is addressed to Bishop Miguel García Franco at the time Bishop of Mazatlán. The response to Bishop Zarza is the second letter. In the first letter, Bishop Zarza recommends to Bishop García Franco the reading and reflection of Michelini's book (where among many supposed dictations from Christ, there is one defending Valtorta's work), on response (second letter) Bishop García wrote: "I received your letter...that came with the book" (Michelini's Book) "...I find all the doctrine contained in the book 100% orthodox, more yet, in whole coincident with the writings of Mrs. Conchita Cabrera de Armida..." (the Venerable Concepción Cabrera de Armida a Mexican mystic in the process of canonization) "... and with the book of Father Esteban Gobbi (In Italian Stefano Gobbi), books for which we have ecclesiastic aprobation".

Imprimatur

Santissima Annunziata Basilica, Florence, the mother church of the Servite Order, where Maria Valtorta is buried.

Over the years, support for Valtorta's work grew among the mid-levels of the Vatican. Her work has received the imprimature of Bishop Roman Danylak and Archbishop Soosa Pakiam.[50][51][52] But the official position of the Holy See with respect to the book is currently less than clear. Since 1993 the Vatican has decided to remain silent on the work[53]

Yet, support for her work continues to appear from unlikely corners of the Vatican, usually from biblical experts who are not at the Holy Office. One such expert was the respected scripture scholar the Venerable Gabriele Allegra, who spent 40 years translating the Bible to Chinese. Allegra wrote:

- "I hold that the work of Valtorta demands a supernatural origin. I think that it is the product of one or more charisma and that it should be studied in the light of the doctrine of charisma."[54][55]

Another expert was the respected Servite Mariologist, Fr. Gabriel M. Roschini, professor at the Pontifical Faculty of Theology in Rome, advisor to the Holy Office and founder of the Marianum (which is both the name of the pontifical school and the prestigious journal of Marian theology)[56] who wrote of Valtorta:

- "I must candidly admit that the Mariology found in Maria Valtorta's writings, whether published or not, has been for me a real discovery. No other Marian writing, not even the sum total of all the writings I have read and studied were able to give me as clear, as lively, as complete, as luminous, or as fascinating an image, both simple and sublime, of Mary, God's masterpiece."[57]

Father Roschini, who published over 900 works on Mariology, presided over the relocation of the remains of Maria Valtorta from Viareggio to the Grand Cloister of Santissima Annunziata Basilica in Florence (the mother church of the Servite Order) in 1973.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Maria Valtorta's death on 12 October 2011, a petition has been started to ask the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith/Vatican to actively promote Valtorta's work.[58] On 12 and 15 October 2011 there will also be Masses in memory of Maria Valtorta in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata in Florence, where Valtorta readers from all over the world will be present.[59][60][61]

References

- ^ Imprimatur for the Writings of Maria Valtorta. Bardstown.com

- ^ The Life of Maria Valtorta.Alphalink.com.au

- ^ Illness-28 years confined to bed

- ^ Overview of Valtorta's Life

- ^ Maria Valtorta's Writings

- ^ a b Introduction to Valtorta

- ^ Poem of the Man God Excerpts.

- ^ Tredici Quote on Valtorta

- ^ Pende Quotes on Valtorta

- ^ Statement by Bishop Roman Danylak Sacredheartofjesus.ca

- ^ a b Peter M. Rookey, "Shepherd of Souls: The Virtuous Life of Saint Anthony Pucci", CMJ Marian Publishers 2003, ISBN 1891280449 p. 2

- ^ Original copy of Corrado Bert's affidavit

- ^ Bishop Roman Danylak, "In Defence of the Poem", A Call to Peace, August/September 1992, Vol. 3, No. 4 Sacreadheartofjesus.ca

- ^ EWTN.com, Eternal Word Television Network

- ^ Code of Canon Law (1917), canon 1385

- ^ Code of Canon Law (1917), canon 1394 §1

- ^ Allen, John (2002-08-30). "A Saint despite the Vatican". National Catholic Reporter. http://natcath.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2002c/083002/083002f.htm.

- ^ Vatican Biography of St. Faustyna Kowalska

- ^ February 26, 1948 Papal Meeting Minutes

- ^ 1992 CEV Newsletter

- ^ Cardinal Edouard Gagnon Statement

- ^ Vatican Cardinal Edouard Gagnon Obituary

- ^ EWTN.com

- ^ Modern History Sourcebook: Index Librorum Prohibitorum

- ^ James Christian, 2005, Philosophy, Thomson Wadsworth, ISBN 053451250X

- ^ Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books.

- ^ Poem Of The Man-God by Fr. John Loughnan on Tripod.com

- ^ Poem of the Man-God by EWTN.com

- ^ La Reporta Valtorta by Fr. Brian Wilson, L.C., Envoymagazine.com

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, 2004, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195154622

- ^ Lee McDonald, 2002, The Canon Debate Hendrikson Publishers ISBN 1565635175

- ^ Bible Gateway, Luke 22:66 Biblegateway.com

- ^ Bible Gateway Matthew 26:57, Biblegateway.com

- ^ Valtorta on Luke 22:66, Valtorta.org

- ^ Analysis of Valtorta's Writing

- ^ Time Magazine article, Time.com

- ^ Bible gateway, John 8:7, Biblegateway.com

- ^ In defense of Valtorta Bardstown.com

- ^ Publisher's Notice in the Second Italian Edition (1986), reprinted in English Edition, Gabriel Roschini, O.S.M. (1989). The Virgin Mary in the Writings of Maria Valtorta (English Edition). Kolbe's Publication Inc. ISBN 2-920285-08-4

- ^ Gabriel Roschini, O.S.M. (1989). The Virgin Mary in the Writings of Maria Valtorta (English Edition). Kolbe's Publication Inc. ISBN 2-920285-08-4, page 7.

- ^ Semper Fi Catholic :: View topic - Marian Helper Problems.../Medjugorje

- ^ Valtorta Publishing

- ^ Mariavaltortawebring.com

- ^ Valepic, Bardstown.com

- ^ Queen of Peace Newsletter (Pittsburgh Center for Peace, P.O. Box 1218, Coraopolis, Pennsylvania 15108): 1988, vol. 1, no. 2.

- ^ "Words from heaven: Messages of Our Lady from Medjugorje: a documented record of the messages and their meanings" page 145. Saint James Publishing, 1990: ISBN 1878909053

- ^ Valtorta Medjugorje confirmation Mariavaltortawebring.com

- ^ Yale University Publishes Article on the Medjugorje Connection to Maria Valtorta

- ^ Vicka Ivanković 1988 interview

- ^ Bishop Danylak's Imprimatur, Bardstown.com

- ^ Archbishop Soosa Pakiam of Trivandrum Mariavaltortawebring.com

- ^ Heart of Jesus Heartofjesus.ca

- ^ Church letter Regarding Valtorta at QC.ca

- ^ Gabriele Allegra on Valtorta Bardstown.com

- ^ Gabriele Allegra on the Poem of the Man God Bardstown.com

- ^ Mariology at Tripod.com

- ^ Gabriel Roschini, O.S.M. (1989). The Virgin Mary in the Writings of Maria Valtorta (English Edition). Kolbe's Publication Inc. ISBN 8879870866

- ^ Petition to the Congregation for Doctrine of the Faith on Change.org

- ^ Ceremonies for 50th anniversary of Maria Valtorta's death Campaign Maria Valtorta

- ^ World Gathering for Maria Valtorta Eucharist Convention, Auckland, New Zealand

- ^ Rassemblement en Florence pour le 50ème anniversaire de la mort de Maria Valtorta Maria-Valtorta.org

Bibliography

- Maria Valtorta, The Poem of the Man God, ISBN 9992645571

- Maria Valtorta, The Book of Azariah, ISBN 8879870130

- Maria Valtorta, The Notebooks 1945-1950 ISBN 8879870882

- Maria Valtorta, Autobiography ISBN 8879870688

Sources and external links

- Msgr Vincenzo Cerri, 1994, The Holy Shroud and the Visions of Maria Valtorta, Kolbe's Publications, ISBN 2920285122

- Maria Valtorta official website

- Foundation Maria Valtorta Cev Onlus

- Bishop Roman Danylak's imprimatur

- Bishop Danylak's Comments on Maria Valtorta

- Petition to the Congregation of the Faith for the promotion of Maria Valtorta's work

- The Venerable Gabriele Allegra on Maria Valtorta

- Valtorta Publishing excerpts

- The Maria Valtorta Network

- The Maria Valtorta Reader’s Group in Australia

- About 20% of Valtorta's writings (in several languages) online

- The Maria Valtorta Web-Ring

- Valtorta Medjugorje confirmation

- Father Mitch Pacwa's critical view

- Response to Fr. Mitch Pacwa

- Response to Colin B. Donovan

- Petition to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith/Vatican

Categories:- 1897 births

- 1961 deaths

- Italian poets

- Italian writers

- Italian nurses

- Italian Roman Catholics

- People from Caserta

- Visions of Jesus and Mary

- Christian mystics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.