- Digamma

-

This article is about the Greek letter. For the mathematical function, see digamma function.

Greek alphabet Αα Alpha Νν Nu Ββ Beta Ξξ Xi Γγ Gamma Οο Omicron Δδ Delta Ππ Pi Εε Epsilon Ρρ Rho Ζζ Zeta Σσς Sigma Ηη Eta Ττ Tau Θθ Theta Υυ Upsilon Ιι Iota Φφ Phi Κκ Kappa Χχ Chi Λλ Lambda Ψψ Psi Μμ Mu Ωω Omega History Archaic local variants

·

·  ·

·  ·

·  ·

·  ·

·

Ligatures (ϛ, ȣ, ϗ) · Diacritics Numerals:  (6) ·

(6) ·  (90) ·

(90) ·  (900)

(900)In other languages Bactrian · Coptic · Albanian Scientific symbols

Book ·

Book ·  Category ·

Category ·  Commons

Commons

Digamma (or wau, uppercase Ϝ, lowercase ϝ; as a numeral symbol: stigma, ϛ) is an archaic letter of the Greek alphabet which originally stood for the sound /w/ and later remained in use only as a numeral symbol for the number "6". Whereas it was originally called wau, its most common appellation in classical Greek is digamma, while in its numeral function it was called episēmon during the Byzantine era. Today the numeral sign is often called stigma, after the value of a Byzantine Greek ligature σ-τ (ϛ), which shares the same shape and was used as a textual ligature in Greek print until the 19th century.

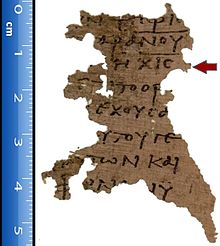

Digamma/wau was part of the original archaic Greek alphabet as initially adopted from Phoenician. Like its model, Phoenician waw, it represented the voiced labial-velar approximant /w/ and stood in the 6th position in the alphabet, between epsilon and zeta. It is the consonantal doublet of the vowel letter upsilon (/u/), which was also derived from waw but was placed at the end of the Greek alphabet. Digamma/wau is in turn the ancestor of the Roman letter F. As an alphabetic letter it is attested in archaic and dialectal ancient Greek inscriptions until the classical period.

The shape of the letter went through a development from

through

through  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  to

to  or

or  , which at that point was conflated with the σ-τ ligature

, which at that point was conflated with the σ-τ ligature  . In modern print, a distinction is made between the letter in its original alphabetic role as a consonant sign, which is rendered as "Ϝ" or its modern lowercase variant "ϝ", and the numeric symbol, which is represented by "ϛ" (or, in modern practice in Greece, replaced with "στ").

. In modern print, a distinction is made between the letter in its original alphabetic role as a consonant sign, which is rendered as "Ϝ" or its modern lowercase variant "ϝ", and the numeric symbol, which is represented by "ϛ" (or, in modern practice in Greece, replaced with "στ").Contents

Greek w

Mycenaean Greek

The sound /w/ existed in Mycenean Greek, as attested in Linear B and archaic Greek inscriptions using digamma. It is also confirmed by the Hittite name of Troy, Wilusa, corresponding to the Greek name *Wilion.

Classical Greek

The /w/ sound was lost at various times in various dialects, mostly before the classical period.

In Ionic, /w/ had probably disappeared before Homer's epics were written down (7th century BC), but its former presence can be detected in many cases because its omission left the meter defective. For example, the words ἄναξ (king), found in the Iliad, which would originally have been ϝάναξ /wánaks/, and οἶνος (wine) are sometimes used in the meter where a word starting with a consonant would be expected. Further evidence coupled with cognate-analysis shows that οἶνος was earlier ϝοῖνος /wóînos/[1] (cf. Cretan Doric ibêna, cf. Latin vīnum and English "wine").

Aeolian was the dialect that kept the sound /w/ longest. In discussions by ancient Greek grammarians of the Hellenistic era, the letter is therefore often described as a characteristic Aeolian feature.

For some time, word-initial /w-/ remained foreign to Greek phonology, and was dropped in loanwords, compare the name of Italy (Italia from Oscan Viteliu *Ϝιτελιυ) or of the Veneti (Greek Ἐνετοί - Enetoi). By the 2nd century BC, the phoneme was once again registered, compare for example the spelling of Οὐάτεις for vates.

Pamphylian digamma

In some local (epichoric) alphabets, a variant glyph of the letter digamma existed that resembled modern Cyrillic И. In one local alphabet, that of Pamphylia, this variant form existed side by side with standard digamma as two distinct letters. It has been surmised that in this dialect the sound /w/ may have changed to labiodental /v/ in some environments. The F-shaped letter may have stood for the new /v/ sound, while the special И-shaped form signified those positions where the old /w/ sound was preserved.[2]

Numeral

Digamma/wau remained in use in the system of Greek numerals attributed to Miletus, where it stood for the number 6, reflecting its original place in the sequence of the alphabet. It was one of three letters that were kept in this way in addition to the 24 letters of the classical alphabet, the other two being koppa (ϙ) for 90, and sampi (ϡ) for 900. During their history in handwriting in late antiquity and the Byzantine era, all three of these symbols underwent several changes in shape, with digamma ultimately taking the form of "ϛ". It has remained in use as a numeral in Greek to the present day, in contexts such as enumerating chapters in a book or other items in a set.

Glyph development

Epigraphy

Digamma was derived from Phoenician waw, which was shaped roughly like an Y (

). Of the two Greek reflexes of waw, digamma retained the alphabetic position, but had its shape modified to

). Of the two Greek reflexes of waw, digamma retained the alphabetic position, but had its shape modified to  , while the upsilon retained the original shape but was placed in a new alphabetic position. Early Crete had an archaic form of digamma somewhat closer to the original Phoenician,

, while the upsilon retained the original shape but was placed in a new alphabetic position. Early Crete had an archaic form of digamma somewhat closer to the original Phoenician,  , or a variant with the stem bent sidewards (

, or a variant with the stem bent sidewards ( ). The shape

). The shape  , during the archaic period, underwent a development parallel to that of epsilon (which changed from

, during the archaic period, underwent a development parallel to that of epsilon (which changed from  to "E", with the arms becoming orthogonal and the lower end of the stem being shed off). For digamma, this led to the two main variants of classical "F" and square

to "E", with the arms becoming orthogonal and the lower end of the stem being shed off). For digamma, this led to the two main variants of classical "F" and square  .[3]

.[3]The latter of these two shapes became dominant when used as a numeral, with "F" only very rarely employed in this function. However, in Athens, both of these were avoided in favour of a number of alternative numeral shapes (

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ).[4]

).[4]Early handwriting

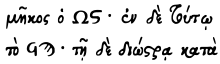

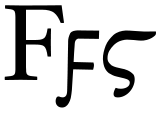

A fragment of Papyrus 115, showing the number "χιϛ" (616, the "Number of the Beast"), with a C-shaped digamma.

A fragment of Papyrus 115, showing the number "χιϛ" (616, the "Number of the Beast"), with a C-shaped digamma.

In cursive handwriting, the square-C form developed further into a rounded form resembling a "C" (found in papyrus manuscripts as

, on coins sometimes as

, on coins sometimes as  ). It then developed a downward tail at the end (

). It then developed a downward tail at the end ( ,

,  ) and finally adopted a shape like a Latin "s" (

) and finally adopted a shape like a Latin "s" ( )[5] These cursive forms are also found in stone inscriptions in late antiquity.[4]

)[5] These cursive forms are also found in stone inscriptions in late antiquity.[4]Conflation with the στ ligature

In the ninth and tenth centuries, the cursive shape digamma was visually conflated with a ligature of sigma (in its historical "lunate" form) and tau (

+

+  =

=  ,

,  ). The στ-ligature had became common in minuscule handwriting from the 9th century onwards. Both closed (

). The στ-ligature had became common in minuscule handwriting from the 9th century onwards. Both closed ( ) and open (

) and open ( ) forms were subsequently used without distinction both for the ligature and for the numeral. The ligature took on the name of "stigma" or "sti", and the name stigma is today applied to it both in its textual and in the numeral function. The association between its two functions as a numeral and as a sign for "st" became so strong that in modern typographic practice in Greece, whenever the ϛʹ sign itself is not available, the letter sequences στʹ or ΣΤʹ are used instead for the number 6.

) forms were subsequently used without distinction both for the ligature and for the numeral. The ligature took on the name of "stigma" or "sti", and the name stigma is today applied to it both in its textual and in the numeral function. The association between its two functions as a numeral and as a sign for "st" became so strong that in modern typographic practice in Greece, whenever the ϛʹ sign itself is not available, the letter sequences στʹ or ΣΤʹ are used instead for the number 6.Typography

In western typesetting during the modern era, the numeral symbol was routinely represented by the same character as the stigma ligature (ϛ). In normal text, this ligature together with numerous others continued to be used widely until the early nineteenth century, following the style of earlier minuscule handwriting, but ligatures then gradually dropped out of use. The stigma ligature was among those that survived longest, but it too became obsolete in print after the mid-19th century. Today it is used only to represent the numeric digamma, and never to represent the sequence στ in text.

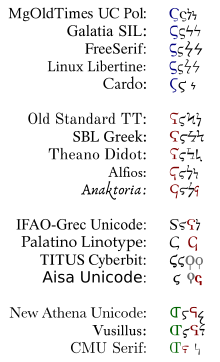

Along with the other special numeric symbols koppa and sampi, numeric digamma/stigma normally has no distinction between uppercase and lowercase forms,[6] (while other alphabetic letters can be used as numerals in both cases). Distinct uppercase versions were occasionally used in the 19th century. Several different shapes of uppercase stigma can be found, with the lower end either styled as a small curved S-like hook (

), or as a straight stem, the latter either with a serif (

), or as a straight stem, the latter either with a serif ( ) or without one (

) or without one ( ). An alternative uppercase stylization in some twentieth-century fonts is

). An alternative uppercase stylization in some twentieth-century fonts is  , visually a ligature of Roman-style uppercase C and T.

, visually a ligature of Roman-style uppercase C and T.The characters used for numeric digamma/stigma are distinguished in modern print from the character used to represent the ancient alphabetic digamma, the letter for the [w] sound. This is rendered in print by a Latin "F", or sometimes a variant of it specially designed to fit in typographically with Greek (Ϝ). It has a modern lowercase form (ϝ) that typically differs from Latin "f" by having two parallel horizontal strokes like the uppercase character, with the vertical stem often being somewhat slanted to the right or curved, and usually descending below the baseline. This character is used in Greek epigraphy to transcribe the text of ancient inscriptions that contain "Ϝ", and in linguistics and historical grammar when describing reconstructed proto-forms of Greek words that contained the sound /w/.

Glyph confusion

Throughout much of its history, the shape of digamma/stigma has often been very similar to that of other symbols, with which it can easily be confused. In ancient papyri, the cursive C-shaped form of numeric digamma is often indistinguishable from the C-shaped ("lunate") form that was then the common form of sigma. The same similarity is still found today, since both the modern stigma (ϛ) and modern final sigma (ς) look identical or almost identical in most fonts; both are historically continuations of their ancient C-shaped forms with the addition of the same downward flourish. If the two characters are distinguished in print, the top loop of stigma tends to be somewhat larger and to extend farther to the right than that of final sigma. The two characters are, however, always distinguishable from the context in modern usage, both in numeric notation and in text: the final form of sigma never occurs in numerals (the number 200 being always written with the medial sigma, σ), and in normal Greek text the sequence "στ" can never occur word-finally.

The medieval s-like shape of digamma (

) has the same shape as a contemporary abbreviation for καὶ ("and").

) has the same shape as a contemporary abbreviation for καὶ ("and").Yet another case of glyph confusion exists in the printed uppercase forms, this time between stigma and the other numeral, koppa (90). In ancient and medieval handriting, koppa developed from

through

through  ,

,  ,

,  to

to  . The uppercase forms

. The uppercase forms  and

and  can represent either koppa or stigma. Frequent confusion between these two values in contemporary printing was already noted by some commentators in the eighteenth century.[7] The ambiguity continues in modern fonts, many of which continue to have glyph similar to

can represent either koppa or stigma. Frequent confusion between these two values in contemporary printing was already noted by some commentators in the eighteenth century.[7] The ambiguity continues in modern fonts, many of which continue to have glyph similar to  for either koppa or stigma.

for either koppa or stigma.Names

The symbol has been called by a variety of different names, referring either to its alphabetic or its numeral function or both.

Wau

Wau (variously rendered as vau, waw or similarly in English) is the original name of the alphabetic letter for /w/ in ancient Greek. It is often cited in its reconstructed acrophonic spelling "ϝαῦ". This form itself is not historically attested in Greek inscriptions, but the existence of the name can be inferred from descriptions by contemporary Latin grammarians, who render it as vav.[8] In later Greek, where both the letter and the sound it represented had become inaccessible, the name is rendered as βαῦ or οὐαῦ. In the 19th century, the anglicized form vau was a common name for the symbol ϛ in its numerical function, used by authors who distinguished it both from the alphabetic "digamma" and from ϛ as a στ ligature.[9]

Digamma

The name digamma was used in ancient Greek and is the most common name for the letter in its alphabetic function today. It literally means "double gamma" and is descriptive of the original letter's shape.

Episemon

The name episēmon was used for the numeral symbol during the Byzantine era and is still sometimes used today, either as a name specifically for digamma/stigma, or as a generic term for the whole group of extra-alphabetic numeral signs (digamma, koppa and sampi). The Greek word "ἐπίσημον", from ἐπί- (epi-, "on") and σήμα (sēma, "sign"), literally means "a distinguishing mark", "a badge", but is also the neuter form of the related adjective "ἐπίσημος" ("distinguished", "remarkable"). This word was connected to the number "six" through early Christian mystical numerology. According to an account of the teachings of the heretic Marcus given by the church father Irenaeus, the number six was regarded as a symbol of Christ, and was hence called "ὁ ἐπίσημος ἀριθμός" ("the outstanding number"); likewise, the name Ἰησοῦς (Jesus), having six letters, was "τὸ ἐπίσημον ὄνομα" ("the outstanding name"), and so on. The sixth-century treatise About the Mystery of the Letters, which also links the six to Christ, calls the number sign to Episēmon throughout.[10] The same name is still found in a fifteenth-century arithmetical manual by the Greek mathematician Nikolaos Rabdas.[11] It is also found in a number of western European accounts of the Greek alphabet written in Latin during the early Middle Ages. One of them is the work De loquela per gestum digitorum, a didactic text about arithmetics attributed to the Venerable Bede, where the three Greek numerals for 6, 90 and 900 are called "episimon", "cophe" and "enneacosis" respectively.[12] From Beda, the term was adopted by the seventeenth century humanist Joseph Justus Scaliger.[13] However, misinterpreting Beda's reference, Scaliger applied the term episēmon not as a name proper for digamma/6 alone, but as a cover term for all three numeral letters. From Scaliger, the term found its way into modern academic usage in this new meaning, of referring to complementary numeral symbols standing outside the alphabetic sequence proper, in Greek and other similar scripts.[14]

Gabex or Gamex

In one remark in the context of a biblical commentary, the 4th century scholar Ammonius of Alexandria is reported to have mentioned that the numeral symbol for 6 was called gabex by his contemporaries.[15][16] The same reference in Ammonius has alternatively been read as gam(m)ex by some modern authors.[17][18] Ammonius as well as later theologians[19] discuss the symbol in the context of explaining the apparent contradiction and variant readings between the gospels in assigning the death of Jesus either to the "third hour" or "sixth hour", arguing that the one numeral symbol could easily have been substituted for the other through a scribal error.

Stigma

The name "stigma" (στίγμα) was originally a common Greek noun meaning "a mark, dot, puncture" or generally "a sign", from the verb στίζω ("to puncture").[20] It had an earlier writing-related special meaning, being the name for a dot as a punctuation mark, used for instance to mark shortness of a syllable in the notation of rhythm.[21] It was then co-opted as a name specifically for the στ ligature, evidently because of the acrophonic value of its initial st- as well as the analogy with the name of sigma. Other names coined according to the same analogical principle are sti[22] or stau.[23][24]

Computer encoding

In Unicode, the sign for the numeral digamma/stigma is present in an uppercase and lowercase version, at U+03DA (Ϛ, "Greek letter stigma") and U+03DB (ϛ, "Greek small letter stigma") respectively. The uppercase letter was present in the standard from version 1.3 (1993), whereas the lowercase equivalent was only added in version 3.0 (1999).[25] [26] (Hence, while the uppercase character may show great differences in shape between different fonts, the lowercase character may be lacking in some older fonts.)

Alphabetic digamma (wau) is present as uppercase U+03DC (Ϝ) and lowercase U+03DD (ϝ).[27] In July 2006, another pair of uppercase and lowercase digamma with bold typeface were added to the Unicode standard version 5.0, at code points U+1D7CA and U+1D7CB. Their intended use is as mathematical symbols, not regular text.

The И-shaped "Pamphylian digamma" was encoded in Unicode version 5.1 and has code U+0376 (uppercase) and U+0377 (lowercase) (Ͷ/ͷ

). The same codepoints are shared with the identical-looking but historically different Arcadian "Tsan". As of 2010, these new characters are not yet supported by most fonts. As these characters have no tradition of typographic representation in mixed-case modern print, new designs for the lowercase letter were created only for Unicode.

). The same codepoints are shared with the identical-looking but historically different Arcadian "Tsan". As of 2010, these new characters are not yet supported by most fonts. As these characters have no tradition of typographic representation in mixed-case modern print, new designs for the lowercase letter were created only for Unicode.A clone of the numeral ϛ for use in Coptic has been encoded separately, since Unicode version 4.1, at U+2C8A ("Coptic capital letter sou", Ⲋ) and U+2C85 ("Coptic small lstter sou", ⲋ). There are also codepoints for an F-shaped sign used as a musical notation symbol in ancient Greek vocal music (U+1D213, "Greek vocal notation symbol-20"), and for a small subscript ϛ-shaped symbol for use in Byzantine musical notation (U+1D0E8, "Byzantine musical symbol stigma").

In Beta code, alphabetic digamma is encoded as "V" (lowercase ϝ) and "*V" (uppercase Ϝ). The numeral sign ("stigma") is encoded as "#2" (lowercase ϛ) and "*#2" (uppercase Ϛ). An additional – now deprecated – code "#4" exists for the ambiguous sign

, which can be a glyph variant either of koppa or of stigma. The F-shaped musical notation symbol is "#567", and the subscript stigma notation symbol is "#2232".[28]

, which can be a glyph variant either of koppa or of stigma. The F-shaped musical notation symbol is "#567", and the subscript stigma notation symbol is "#2232".[28]In the LaTeX typesetting system, the "Babel" package allows accessing digamma through the commands "\digamma" (ϝ), "\Digamma" (Ϝ), "\stigma" (ϛ), "\Stigma" (which produces the modern ligature CT glyph

), and "\varstigma" (which produces a variant of the S-shaped form).[29]

), and "\varstigma" (which produces a variant of the S-shaped form).[29]References

- ^ οἶνος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at Perseus Project:

- ^ Nick Nicholas: Proposal to add Greek epigraphical letters to the UCS. Technical report, Unicode Consortium, 2005. Citing C. Brixhe, Le dialecte grec de Pamphylie. Documents et grammaire. Paris: Maisonneuve, 1976.

- ^ Jeffery, Lilian H. (1961). The local scripts of archaic Greece. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 24f..

- ^ a b Tod, Marcus N. (1950). "The alphabetic numeral system in Attica". Annual of the British School at Athens 45: 126–139.

- ^ Gardthausen, Victor Emil (1879). Griechische Palaeographie, Vol. 2. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. p. 367.

- ^ Holton, David; Mackridge, Peter; Philippaki-Warburton, Irene (1997). Greek: a comprehensive grammar of the modern language. London: Routledge. p. 105.

- ^ Adelung, Johann Christoph (1761). Neues Lehrgebäude der Diplomatik, Vol.2. Erfurt. p. 137f..

- ^ Cf. Grammatici Latini (ed. Keil), 7.148.

- ^ Buttmann, Philipp (1839). Buttmann's larger Greek grammar: a Greek grammar for use of high schools and universities. New York. p. 22.

- ^ Bandt, Cordula (2007). Der Traktat "Vom Mysterium der Buchstaben." Kritischer Text mit Einführung, Übersetzung und Kommentar. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ^ Einarson, Benedict (1967). "Notes on the development of the Greek alphabet". Classical Philology 62: 1–24; especially p.13 and 22.

- ^ Beda [Venerabilis]. "De loquela per gestum digitorum". In Migne, J.P.. Opera omnia, vol. 1. Paris. p. 697.

- ^ Scaliger, Joseph Justus. Animadversiones in Chronologicis Eusebii pp. 110–116.

- ^ Wace, Henry (1880). "Marcosians". Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century.

- ^ Estienne, Henri; Hase, Charles Benoit (n.d.). "γαβέξ". Thesauros tes hellenikes glosses. Paris. p. 479. http://books.google.com/books?id=NaxJAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA479&dq=%CE%B3%CE%B1%CE%B2%CE%AD%CE%BE&hl=en&ei=JTGHTu6mG46g-AaP_JkR&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CEMQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Migne, Patrologia Graeca 85, col. 1512 B.

- ^ Jannaris, A. N. (1907). "The Digamma, Koppa, and Sampi as numerals in Greek". The Classical Quarterly 1: 37–40.

- ^ von Tischendorf, Constantin (1859). Novum Testamentum graece. Leipzig. p. 679.

- ^ Bartina, Sebastian (1958). "Ignotum episemon gabex". Verbum Domini: 16–37.

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940. s.v. "στίγμα"

- ^ Beare, William (1957). Latin Verse and European Song. London: Methuen. p. 91.

- ^ Samuel Brown Wylie, An introduction to the knowledge of Greek grammar (1838), p. 10.

- ^ K. Barry, The Greek Qabalah: alphabetic mysticism and numerology in the ancient world (1999), p.17

- ^ Thomas Shaw Brandreth, A dissertation on the metre of Homer (1844), p.135.

- ^ Everson, Michael (1998). "Additional Greek characters for the UCS" (PDF). http://anubis.dkuug.dk/jtc1/sc2/wg2/docs/n1743.pdf.

- ^ Unicode Consortium. "Unicode Character Database: Derived Property Data". http://www.unicode.org/Public/UNIDATA/DerivedAge.txt. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ^ Unicode Character 'GREEK LETTER DIGAMMA' (U+03DC)

- ^ "The TLG Beta Code Manual 2010". http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/encoding/BCM2010.pdf.

- ^ Beccari, Claudio (2010). "Teubner.sty: An extension to the greek option of the babel package" (PDF). http://mirror.ctan.org/macros/latex/contrib/teubner/teubner-doc.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

Sources

- Peter T. Daniels – William Bright (edd.), The World's Writing Systems, New York, Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0195079930

- Jean Humbert, Histoire de la langue grecque, Paris, 1972.

- Michel Lejeune, Phonétique historique du mycénien et du grec ancien, Klincksieck, Paris, 1967. ISBN 2252034963

- "In Search of The Trojan War", pp. 142–143,187 by Michael Wood, 1985, published by BBC.

External links

- Perseus Project: lexicon search for words starting with or containing digamma

Greek language · Eλληνική γλώσσα History Proto-Greek (c. 3000–1600 BC) · Mycenaean (c. 1600–1000 BC) · Ancient Greek (c. 1000–330 BC) · Koine Greek (c. 330 BC–330) · Medieval Greek (330–1453) · Modern Greek (from 1453)

Alphabet Letters Phonology Grammar Dialects Cappadocian · Cretan · Cypriot · Chalkidiki · Demotic · Greek-Calabrian · Griko · Katharevousa · Macedonian · Misthiotica · Pontic · Tsakonian · YevanicLiterature Related Topics Promotion and Study Categories:- Greek letters

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.