- University of Manchester

-

The University of Manchester

Arms of the University of Manchester. The Manchester bee is the main symbol of Manchester.Motto Latin: Cognitio, sapientia, humanitas Motto in English "Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity" Established 2004, by the merger of the Victoria University of Manchester (established 1851) and UMIST (established 1824) Endowment £127m (2009)[1] Chancellor Tom Bloxham Vice-Chancellor Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell DBE Admin. staff 10,407 Students 39,165[2] Undergraduates 27,310[2] Postgraduates 11,850[2] Location Manchester, United Kingdom Campus Urban and Suburban Nobel Laureates 25[3] Colours Blue, Gold, Purple

Affiliations Russell Group, EUA, N8 Group, NWUA, ACU Website manchester.ac.uk The University of Manchester is a public research university located in Manchester, United Kingdom. It is a "red brick" university and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive British universities and the N8 Group. The university was formed in October 2004 by the merger of the Victoria University of Manchester (which was commonly known as the University of Manchester) and UMIST (University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology). The University of Manchester and its constituent former institutions have 25 Nobel Laureates among their past and present students and staff, the third highest number of any single university in the United Kingdom (after Cambridge and Oxford). Four Nobel laureates are currently among its staff - Andre Geim (Physics, 2010), Kostya Novoselov (Physics, 2010), Sir John Sulston (Physiology and Medicine, 2002) and Joseph Stiglitz (Economics, 2001).

Following the merger, the university was named Sunday Times University of the Year in 2006 after winning the inaugural Times Higher Education Supplement University of the Year prize in 2005.[4] According to The Sunday Times, "Manchester has a formidable reputation spanning most disciplines, but most notably in the life sciences, engineering, humanities, economics, sociology and the social sciences".[5]

In 2007/08, the University of Manchester had over 40,000 students studying 500 academic programmes and more than 10,000 staff, making it the largest single-site university in the United Kingdom.[6] More students try to gain entry to the University of Manchester than any other university in the country, with more than 60,000 applications for undergraduate courses alone.[5] The University of Manchester had a total income of £787.9 million in 2009/10 (the third-highest of any university in the UK after Cambridge and Oxford), of which £194.6 million was from research grants and contracts.[7][8]

In the first national assessment of higher education research since the university’s founding, the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise,[9] the University of Manchester came 3rd in terms of research power after Cambridge and Oxford and 8th for grade point average quality when including specialist institutions.[10] In the 2011 Academic Ranking of World Universities, Manchester is ranked 38th in the world, 6th in Europe and 5th in the UK.[11] The university has also been ranked 29th in the world, 8th in Europe and 7th in the UK in the 2011 QS World University Rankings.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Campus and facilities

- 3 Research and reputation

- 4 Student life

- 5 Medicine

- 6 Notable academic staff and alumni

- 7 See also

- 8 Notes

- 9 External links

History

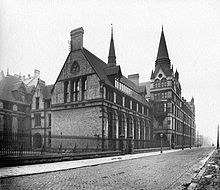

Main articles: UMIST and Victoria University of Manchester The university's Whitworth Hall; this archway was the inspiration for the logo of the Victoria University of Manchester

The university's Whitworth Hall; this archway was the inspiration for the logo of the Victoria University of Manchester

The University can trace its roots as an academic institution back to the formation of the Mechanics' Institute in 1824 and it is closely linked to Manchester's emergence as the world's first industrial city.[12] The English chemist John Dalton, together with Manchester businessmen and industrialists, established the Mechanics' Institute (later to become UMIST) to ensure that workers could learn the basic principles of science. Similarly, John Owens, a Manchester textile merchant, left a bequest of £96,942 in 1846 for the purpose of founding a college for the education of males on non-sectarian lines. His trustees established Owens College at Manchester in 1851. It was initially housed in a building, complete with Adam staircase, on the corner of Quay Street and Byrom Street which had been the home of the philanthropist Richard Cobden, and subsequently was to house Manchester County Court. In 1873 it moved to new buildings at Oxford Road, Chorlton-on-Medlock and from 1880 it was a constituent college of the federal Victoria University. The university was established and granted a Royal Charter in 1880 to become England's first civic university; it was renamed the Victoria University of Manchester in 1903 and then absorbed Owens College the following year.[13]

By 1905, the two institutions were large and active forces in the area, with the Municipal College of Technology, the forerunner of the later UMIST, forming the Faculty of Technology of the Victoria University of Manchester while continuing as a technical college in parallel with the advanced courses of study in the Faculty. Although UMIST achieved independent university status in 1955, the two universities continued to work together.[12]

Before the merger, Victoria University of Manchester and UMIST between them counted 23 Nobel Prize winners amongst their former staff and students. Manchester has traditionally been particularly strong in the sciences, with the nuclear nature of the atom being discovered at Manchester by Rutherford, and the world's first stored-program computer coming into being at the university. Famous scientists associated with the university include the physicists Osborne Reynolds, Niels Bohr, Ernest Rutherford, James Chadwick, Arthur Schuster, Hans Geiger, Ernest Marsden and Balfour Stewart. However, the university has also contributed in many other fields, such as by the work of the mathematicians Paul Erdős, Horace Lamb and Alan Turing; the author Anthony Burgess; philosophers Samuel Alexander, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Alasdair MacIntyre; the Pritzker Prize and RIBA Stirling Prize winning architect Norman Foster and the composer Peter Maxwell Davies all attended, or worked in, Manchester. Well-known figures among the current academic staff include computer scientist Steve Furber, economist Richard Nelson,[14] novelist Colm Tóibín[15] and biochemist Sir John Sulston, Nobel laureate of 2002.

In 2004, the Victoria University of Manchester (established in 1851) and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (established in 1824) were formally merged into a single institution.

The university today

The Sackville Street Building, formerly known as UMIST Main building

The Sackville Street Building, formerly known as UMIST Main building

The newly merged University of Manchester was officially launched on 1 October 2004 when the Queen handed over the Royal Charter. It has the largest number of full time students in the UK, unless the University of London is counted as a single university. It teaches more academic subjects than any other British university. The founding President and Vice-Chancellor of the new university was Alan Gilbert, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne, who retired at the end of the 2009-2010 academic year.[16] The current vice chancellor is Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell, who held a chair in physiology at the university since 1994. One of the university's aims stated in the Manchester 2015 Agenda is to be one of the top 25 universities in the world. This follows Alan Gilbert's aim for the university to 'establish it by 2015 among the 25 strongest research universities in the world on commonly accepted criteria of research excellence and performance'.[17] Manchester has the largest total income of all UK universities, standing at £637 million as of 2007.[8] Its research income of £216 million is the fifth largest of any university in the country. As of 2011, four Nobel laureates are currently among its staff: Andre Geim, Konstantin Novoselov, Sir John Sulston and Joseph E. Stiglitz.

Campus and facilities

The main site of the University contains the vast majority of its facilities and is often referred to simply as campus. Despite this, Manchester is not a campus university as the concept is commonly understood. It is centrally located and the buildings of the main site are integrated into the fabric of Manchester, with non-university buildings and major roads between them.

Campus occupies an area shaped roughly like a boot: the foot of the boot is aligned roughly south-west to north-east and is joined to the broader southern part of the boot by an area of overlap between former UMIST and former VUM buildings;[18] it comprises two parts:

- North campus, centred on Sackville Street

- South campus, centred on Oxford Road.

These names are not officially recognised by the University, but are commonly used, including in parts of its website; another usage is Sackville Street Campus and Oxford Road Campus. They roughly correspond to the campuses of the old UMIST and Victoria University respectively, although there was already some overlap before the merger.

Fallowfield Campus is the main residential campus of the University. It is located in Fallowfield, approximately 2 miles (3 km) south of the main site.

There are a number of other university buildings located throughout the city and the wider region, such as One Central Park (in the northern suburb of Moston)[19] and Jodrell Bank Observatory (in the nearby county of Cheshire). The former is a collaboration between Manchester University and other partners in the region which offers office space to accommodate new start-up firms as well as venues for conferences and workshops.

Despite its size, the University of Manchester is divided into only four faculties, each sub-divided into schools:

- Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences consisting of the Schools of Medicine; Dentistry; Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work; Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; and Psychological Sciences.

- Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences consisting of the Schools of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Science; Chemistry; Computer Science; Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Science; Physics and Astronomy; Electrical & Electronic Engineering; Materials; Mathematics; and Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering.

- Faculty of Humanities includes the School of Arts, Histories and Cultures (incorporating Archaeology; Art History & Visual Studies; Classics and Ancient History; Drama; English and American Studies; History; Museology; Music; and Religions and Theology). The other Schools are Combined Studies; Education; Environment and Development; Architecture; Languages, Linguistics and Cultures; Law; Social Sciences and the Manchester Business School.

- Faculty of Life Sciences unusually consisting of a single school.

Major projects

The atrium inside the new £38m Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre

The atrium inside the new £38m Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre

Following the merger, the University embarked on a £600 million programme of capital investment, to deliver eight new buildings and 15 major refurbishment projects by 2010, partly financed by a sale of unused assets.[20] These include:

- £60 m Flagship University Place building (new)

- £56 m Alan Turing Building: housing Mathematics, the Photon Sciences Institute and the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics (new)

- £50 m Life Sciences Research Building (A. V. Hill Building) (new)

- £38 m Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre (MIB) (new)

- £33 m Life Sciences and Medical and Human Sciences Building (Michael Smith Building) (new)

- £31 m Humanities Building - now officially called the "Arthur Lewis Building" (new)

- £20 m Wolfson Molecular Imaging Centre (WMIC) (new)

- £18 m Re-location of School of Pharmacy

- £17 m John Rylands Library, Deansgate (new extension & refurbishment of existng building)

- £13 m Chemistry Building

- £10 m Functional Biology Building

John Rylands University Library

Main article: John Rylands University LibraryThe university's library, the John Rylands University Library, is the largest non-legal deposit library in the UK, as well as being the UK's third-largest academic library after those of Oxford and Cambridge.[21] It also has the largest collection of electronic resources of any library in the UK.[21]

The oldest part of the library, the John Rylands Library, founded in memory of John Rylands by his wife Enriqueta Augustina Rylands as an independent institution, is situated in a Victorian Gothic building on Deansgate, Manchester city centre. This site houses an important collection of historic books and other printed materials, manuscripts, including archives and papyri. The papyri are in various ancient languages and include the oldest extant New Testament document, Rylands Library Papyrus P52, commonly known as the St John Fragment. In April 2007 the Deansgate site reopened to readers and the public, following major improvements and renovations, including the construction of the pitched roof originally intended and a new wing in Spinningfield.

Jodrell Bank Observatory

Main article: Jodrell Bank ObservatoryThe Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics is a combination of the astronomical academic staff, situated in Manchester, and the Jodrell Bank Observatory in rural land near Goostrey, about ten miles (16 km) west of Macclesfield away from the lights of Greater Manchester. The observatory boasts the third largest fully movable radio telescope in the world, the Lovell Telescope, constructed in the 1950s. It has played an important role in the research of quasars, pulsars and gravitational lenses, and has played a role in confirming Einstein's theory of General Relativity.

Manchester Museum

Main article: Manchester MuseumThe Manchester Museum holds nearly 4.25 million[22] items sourced from many parts of the world. The collections include butterflies and carvings from India, birds and bark-cloth from the Pacific, live frogs and ancient pottery from America, fossils and native art from Australia, mammals and ancient Egyptian craftsmanship from Africa, plants, coins and minerals from Europe, art from past civilisations of the Mediterranean, and beetles, armour and archery from Asia. In November 2004, the museum acquired a cast of a fossilised Tyrannosaurus rex called "Stan".

The history of the museum goes back to 1821, when the first collections were assembled by the Manchester Society of Natural History and later increased by those of the Manchester Geological Society. Due to the society's financial difficulties and on the advice of the great evolutionary biologist Thomas Huxley, Owens College accepted responsibility for the collections in 1867. The college commissioned Alfred Waterhouse, the architect of London’s Natural History Museum, to design a museum building to house these collections for the benefit of students and the public on a new site in Oxford Road. The Manchester Museum was finally opened to the public in 1888.[23]

Whitworth Art Gallery

Main article: Whitworth Art GalleryThe Whitworth Art Gallery is home to collections of internationally famous British watercolours, textiles and wallpapers, as well as of modern and historic prints, drawings, paintings and sculpture. It contains some 31,000 items in its collection. A programme of temporary exhibitions runs throughout the year, with the Mezzanine Court serving as a venue for showing sculpture. It was founded by Robert Darbishire with a donation from Sir Joseph Whitworth in 1889, as The Whitworth Institute and Park. 70 years later in 1959 the gallery became officially part of the University of Manchester.[24] In October 1995 a Mezzanine Court in the centre of the building was opened. This new gallery, designed chiefly for the display of sculptures, won a RIBA regional award.[citation needed]

Manchester University Press

Main article: Manchester University PressManchester University Press is an academic publishing house which exists as part of the university. It publishes academic monographs as well as textbooks and journals, the majority of which are works from authors based elsewhere in the international academic community, and is the third largest university press in England after Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press.

Contact Theatre

The Contact Theatre

The Contact Theatre Main article: Contact Theatre

Main article: Contact TheatreThe Contact Theatre largely stages modern live performance and participatory work for younger audiences. The present fortress-style building on Devas Street was completed in 1999 but incorporates parts of its 1960s predecessor.[25] It features a unique energy-efficient system, using its high towers to naturally ventilate the building without the use of air conditioning. The colourful and curvaceous interior houses three performance spaces, a lounge bar and Hot Air, a reactive public artwork in the foyer.

Old Quadrangle

The buildings around the Old Quadrangle date from the time of Owens College, and were designed in a Gothic style by Alfred Waterhouse (and his son Paul Waterhouse). The first to be built (in 1873) was the John Owens Building (formerly the Main Building: the others were added over the next thirty years. In fact, the Rear Quadrangle is older than the Old Quadrangle. Today, the museum continues to occupy part of one side (including the tower) and the grand setting of the Whitworth Hall is used for the conferment of degrees. Part of the old Christie Library (1898) now houses Christie's Bistro, and the remainder of the buildings house administrative departments.

Chancellors Hotel and Conference Centre

Main article: Chancellors Hotel & Conference CentreMain article: Manchester Conference CentreFormerly named The Firs, the original house was built in 1850 for Sir Joseph Whitworth by Edward Walters, who was also responsible for Manchester’s Free Trade Hall and Strangeways Prison. Whitworth used The Firs mainly as a social, political and business base, entertaining radicals of the age such as John Bright, Richard Cobden, William Forster and T.H. Huxley at the time of the Reform Bill of 1867. Whitworth, credited with raising the art of machine-tool building to a previously unknown level, supported the new Mechanics Institute in Manchester – the birthplace of UMIST - and helped to found the Manchester School of Design. Whilst living in the house, Whitworth used land to the rear (now the site of the University's botanical glasshouses) for testing his "Whitworth rifle". In 1882, the Firs was leased to C.P. Scott, Editor of the Manchester Guardian. After Scott's death the house became the property of Owens College, and was the Vice-Chancellor's residence until 1991. The old house now forms the western wing of Chancellors Hotel & Conference Centre at the University. The newer eastern wing houses the circular Flowers Theatre, six individual conference rooms and the majority of the 75 hotel bedrooms.

Residential accommodation

Before they merged, the two former universities had for some time been sharing their residential facilities.

Main campus

- Whitworth Park Halls of Residence

These halls are owned by the University of Manchester and house 1,085 students of that university.[26] It is most notable for the unique triangular shape of the accommodation blocks which gave rise to the nickname of "Toblerones", after the chocolate bar.

The designer of these unique 'Toblerone' shaped buildings took his inspiration from the hill which has been there since 1962, when as a result of a nearby archaeological dig (led by John Gater) the hill was created from the excavated soil. A consequence of this triangular design was a much reduced cost for the contracted construction company. Due to a deal struck between the University and Manchester City Council, which meant that the council would pay for the roofs of all student residential buildings in the area, Allan Pluen's team is believed to have saved thousands on the final cost of the halls. They were built in the mid 1970s.

It is also said by alumni, that the then University of Victoria got a grant for building the halls, and the then government would pay for the roof if they paid for the rest, hence they made very large roofs and not many bricks.[citation needed]

The site of the halls was previously occupied by many small streets whose names have been preserved in the names given to the halls. Grove House is a much older building and has been used by the University for many different purposes over the last sixty years. Its first occupants in 1951 were the Appointments Board and the Manchester University Press.[27] The shops in Thorncliffe Place were part of the same plan and include banks and a convenience store.

Notable people associated with the halls are Friedrich Engels whose residence on the site is commemorated by a blue plaque on Aberdeen House; the physicist Brian Cox; Irene Khan, Secretary general of Amnesty International; and Big Brother winner Omar Chaparro.[citation needed]

- Sackville Street

The former UMIST Campus has five halls of residence near to Sackville Street building (Weston, Lambert, Fairfield, Chandos, and Wright Robinson), and several other halls within a 5-15 minute walk away, such as the Grosvenor group of halls.

- Other accommodation

The former Moberly Tower has been demolished. There are also Vaughan House (once the home of the clergy serving the Church of the Holy Name)and George Kenyon Hall at University Place; Crawford House and Devonshire House adjacent to the Manchester Business School and Victoria Hall in Higher Cambridge Street.

Fallowfield and Victoria Park Campuses

The Fallowfield Campus, situated 2 miles (3.2 km) south of the main university campus (the Oxford Road Campus), is the largest of the university's residential campuses. The Owens Park group of halls with its landmark tower lies at the centre of it, while Oak House is another large hall of residence. Woolton Hall is also on the Fallowfield campus next to Oak House. Allen Hall is a traditional hall situated near Ashburne Hall (Sheavyn House being annexed to Ashburne). Richmond Park is also a relatively recent addition to the campus.

Victoria Park Campus, comprises several halls of residence. Among these are St Anselm Hall with Canterbury Court and Pankhurst Court, Dalton-Ellis Hall, Hulme Hall (including Burkhardt House), St Gabriel's Hall and Opal Gardens Hall. St Anselm Hall is the only all-male hall left in the United Kingdom.

Research and reputation

Rankings ARWU[28]

(2011/12, national)5 ARWU[28]

(2011/12, world)38 QS[29]

(2011/12, national)7 QS[29]

(2011/12, world)29 THE[30]

(2011/12, national)7 THE[30]

(2011/12, world)48 Complete/The Independent[31]

(2012, national)29 The Guardian[32]

(2012, national)41 The Sunday Times[33]

(2012, national)37 The Times[34]

(2012, national)32 The university has a very high quality research profile and is counted among the leading universities in the world. In addition to being a member of the prestigious Russell Group, Manchester is also included in the Sutton Trust's list of highly selective 'elite' UK institutions.[35] In the first national assessment of higher education research since the university’s founding, the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise, the University of Manchester came 3rd in terms of research power after Cambridge and Oxford and 6th for grade point average quality[36] (8th when including specialist institutions).[10] Accordingly, Manchester enjoys the largest amount of research funding behind Oxbridge, UCL and Imperial[37] (these five universities being informally referred to as the 'golden diamond' of research-intensive UK institutions[38]). Manchester also has a particularly strong presence in terms of funding from the three main UK research councils, EPSRC, MRC and BBSRC, being ranked 5th,[39] 7th[40] and 1st[41] respectively. In addition, the university is also one of the richest in the UK in terms of income and interest from endowments: at a recent rank it was placed at 3rd place behind Oxbridge.[42] Despite the recent severe cuts in higher education Manchester remains at second place behind Oxford nationally in terms of total recurrent grants allocated by the HEFCE.[43]

Historically, Manchester has been linked with high scientific achievement: the university and its constituent former institutions combined had 25 Nobel Laureates among their students and staff, the third largest number of any single university in the United Kingdom behind Oxford and Cambridge. Purely in terms of Nobel prize winners Manchester is ranked 9th in Europe. Furthermore, according to an academic poll two of the top ten discoveries by university academics and researchers were made at the University (namely the first working computer and the contraceptive pill).[44] The university currently employs 4 Nobel Prize winners amongst its staff, more than any other in the UK.[45]

The 2009 THE - QS World University Rankings found Manchester overall 26th in the world. It was also ranked by the same report 5th internationally by employer reviews (along with MIT and Stanford and ahead of Yale and Cornell) by receiving a maximum 100% rating which the university has retained since 2008.[46][47] The separate 2011 QS World University Rankings[48] found that Manchester had slipped to 29th overall in the world(in 2010 Times Higher Education World University Rankings and QS World University Rankings parted ways to produce separate rankings).

The Academic Ranking of World Universities 2008 published by the Institute of Higher Education of Shanghai Jiao Tong University ranked Manchester 5th in the UK, 6th in Europe and 40th in the world.[49] After several years of steady progress Manchester fell back in 2009 to 41st in the world and 7th in Europe,[50] falling back further to 44th in the world and 9th in Europe in 2010.[51] Excluding US universities, Manchester is ranked 13th and 11th in the world for 2009 by THES and ARWU respectively. According to the ARWU rankings the university is ranked 9th in Europe for natural sciences[52] and 4th in engineering.[53] Similarly the HEEACT 2009 rankings for scientific performance place Manchester 5th in Europe for engineering,[54] 8th for natural sciences[55] and 3rd for social sciences.[56] And finally THES ranks Manchester 6th in Europe for technology,[57] 10th for life sciences[58] and 7th for social sciences.[59] More recently a survey by the Times Higher Education Supplement has shown that Manchester is placed 6th in Europe in the area of Psychology & Psychiatry.[60] According to a further ranking by SCImago Research Group Manchester is ranked 8th in Europe amongst higher education institutions in terms of sheer research output.[61] In terms of research impact a further ranking places Manchester 6th in Europe.[62] Manchester is also one of only seven universities in Europe which are rated Excellent in all seven main academic departments (Biology, Chemistry, Mathematics, Physics, Psychology, Economics and Political Science) by the 2010 Centre for Higher Education's Development's Excellence Rankings.[63] The Manchester Business School is currently ranked 29th worldwide (4th nationally) by the Financial Times.[64] The latest THES rankings place Manchester 11th in Europe with respect to research volume, income and reputation[65] and 7th in the UK.

According to the High Fliers Research Limited's survey, University of Manchester students are being targeted by more top recruiters for graduate vacancies than any other UK university students for three consecutive years (2007–2009).[66][67] Furthermore the university has been ranked joint 20th in the world for 2009 according to the Professional Ranking of World Universities.[68] Its main compilation criterion is the number of Chief Executive Officers (or number 1 executive equivalent) which are among the "500 leading worldwide companies" as measured by revenue who studied in each university. The ranking places the University only behind Oxford nationally. Manchester is ranked 5th among British universities according to a popularity ranking which is based on the degree of traffic that a university's website attracts.[69] Also a further report places Manchester within the top 20 universities outside the US.[70] Manchester was also given a prestigious award for Excellence and Innovation in the Arts by the Times Higher Education Awards 2010.[71]

At a recent ranking undertaken by the Guardian, Manchester is placed 5th in the UK in international reputation behind the usual four: Oxbridge, UCL and Imperial.[72] Furthermore, according to the latest QS World University Rankings, Manchester is ranked 4th in Europe strictly in terms of both academic and employer reputation.[73] However, while as a rule world rankings (such as the ARWU, THES and HEEACT[74]) typically place the university within the top 10 in Europe, national studies are less complimentary; The Times 'Good University Guide 2011’[75] ranked Manchester 30th out of 113 Universities in the UK, ‘The Complete University Guide 2012' in association with The Independent placed it at 29th out of 116 universities[76] whilst ‘The Guardian University Guide 2012’ ranked Manchester at 41st out of 119 universities in the UK.[77] This apparent paradox is mainly a reflection of the different ranking methodologies employed by each listing: global rankings focus on research and international prestige, whereas national rankings are largely based on teaching and the student experience.

Student life

The University's Boat Club is one of many Athletic Union Clubs that Manchester offers.[78]

The University's Boat Club is one of many Athletic Union Clubs that Manchester offers.[78]

Athletics and outdoor games

Unlike some universities, the University of Manchester operates its own sports clubs via the Athletics Union. Student societies on the other hand are operated by the Students' Union.

Today the university can boast more than 80 health and fitness classes while over 3,000 students are members of the 44 various Athletic Union clubs. The sports societies in Manchester vary widely in their level and scope. Many of the more popular sports have several university teams as well as departmental teams which may be placed in a league against other teams within the university. Common teams include: lacrosse, korfball, dodgeball, hockey, rugby league, rugby union, football, basketball, netball and cricket. The Manchester Aquatics Centre, the swimming pool used for the Manchester Commonwealth Games is also on the campus.

The university competes annually in 28 different sports against Leeds and Liverpool universities in the Christie Cup, which Manchester has won for seven consecutive years.[79] The university has also achieved considerable success in the BUCS (British University & College Sports) competitions, with the mens water polo 1st team winning the national championships in both 2009 and 2010. It was positioned in eighth place in the overall BUCS rankings for 2009/10[80] The Christie Cup is an inter-university competition between Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester in numerous sports since 1886. After the Oxford and Cambridge rivalry, the Christie's Championships is the oldest Inter–University competition on the sporting calendar: the cup was a benefaction of Richard Copley Christie.

Every year elite sportsmen and sportswomen at the university are selected for membership of the XXI Club, a society that was formed in 1932 and exists to promote sporting excellence at the university. Most members have gained a Full Maroon for representing the university and many have excelled at a British Universities or National level.

University Challenge

The university has done particularly well in recent years on the BBC2 quiz programme University Challenge. In 2006, Manchester beat Trinity Hall, Cambridge, to record the university's first triumph in the competition. The year after, the university finished in second place after losing out to the University of Warwick in the final. The team has progressed to the semi-finals every year since 2005.

In 2009, the team battled hard in the final against Corpus Christi College, Oxford. At the gong, the score was 275 - 190 to Corpus Christi College after an extraordinary performance from Gail Trimble. However, the title was eventually given to the University of Manchester after it was discovered that Corpus Christi team member Sam Kay had graduated eight months before the final was broadcast, so that the team was disqualified.

Manchester reached the semi-finals in the 2010 competition before being beaten by Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Medicine

The origins of the Manchester Medical School go back to the The School of Anatomy established at Manchester Royal Infirmary by Joseph Jordan in 1814. Medical education has continued there since this time. The college was formally established in 1874 and is one of the largest in the country,[81] with over 400 medical students being trained in each of the clinical years and over 350 students in the pre-clinical/phase 1 years. Approximately 100 students who have completed pre-clinical training at the Bute Medical School (University of St Andrews) join the third year of the undergraduate medical programme each year.

The university's Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences has links with a large number of NHS hospitals in the North West of England and maintains presences in its four base hospitals: Manchester Royal Infirmary (located at the southern end of the main university campus on Oxford Road), Wythenshawe Hospital, Hope Hospital and the Royal Preston Hospital. All are used for clinical medical training for doctors and nurses.

In 1883, a dedicated department of pharmacy was established at the University and, in 1904, Manchester became the first British university to offer an Honours degree in the subject. The School of Pharmacy[82] also benefits from the university's links with the Manchester Royal Infirmary and Wythenshawe and Hope hospitals. All of the undergraduate pharmacy students gain hospital experience through these links and are the only pharmacy students in the UK to have an extensive course completed in secondary care.[83] Moreover, the university is a founding partner of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, established to focus high-end healthcare research in Greater Manchester.[84]

Future development plans include collaboration plans with Manchester City Football Club and the National Health Service (NHS) to establish a world-leading research facility on sports science and treatment in Sportcity.[85] Further details of the plans are expected to be revealed in the summer of 2011.

Notable academic staff and alumni

Main article: People associated with the University of Manchester- see also List of University of Manchester people

Many notable and famous people have worked or studied at one or both of the two former institutions that merged to form the University of Manchester, including 25 Nobel prize laureates. Some of the best known include John Dalton (founder of modern atomic theory), Ludwig Wittgenstein (considered one of the most significant philosophers of the 20th century), George E. Davis (founded the discipline of Chemical Engineering), Bernard Lovell (a pioneer of radio astronomy), Alan Turing (one of the founders of computer science and artificial intelligence), Tom Kilburn and Frederic Calland Williams (both who developed Small-Scale Experimental Machine(SSEM) or "Baby", the world's first stored-program computer at Victoria University of Manchester in 1948), Irene Khan (current secretary general of Amnesty International) and Robert Bolt (two times Academy Award winner and three times Golden Globe winner for screenwriting Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago). Additionally, a number of politicians are associated with the university, including the current Presidents of Belize, Iceland and Trinidad and Tobago, as well as several ministers among others in the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Canada and Singapore and also Chaim Weizmann, a chemist and the first President of Israel.

Nobel prize winners

Overall, there have been 25 Nobel Prizes awarded to staff and students past and present, with some of the most important discoveries of the modern age being made in Manchester.

Chemistry

- Ernest Rutherford (awarded Nobel prize in 1908), for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements and the chemistry of radioactive substances (He was the first to probe the atom).

- Arthur Harden (awarded Nobel prize in 1929), for investigations on the fermentation of sugar and fermentative enzymes.

- Walter Haworth (awarded Nobel prize in 1937), for his investigations on carbohydrates and vitamin C.

- George de Hevesy (awarded Nobel prize in 1943), for his work on the use of isotopes as tracers in the study of chemical processes.

- Robert Robinson (awarded Nobel prize in 1947), for his investigations on plant products of biological importance, especially the alkaloids.

- Alexander Todd (awarded Nobel prize in 1957), for his work on nucleotides and nucleotide co-enzymes.

- Melvin Calvin (awarded Nobel prize in 1961), for his research on the carbon dioxide assimilation in plants.

- John Charles Polanyi (awarded Nobel prize in 1986), for his contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes.

- Michael Smith (awarded Nobel prize in 1993), for his fundamental contributions to the establishment of oligonucleotide-based, site-directed mutagenesis and its development for protein studies.

Physics

- Joseph John (J. J.) Thomson (awarded Nobel prize in 1906), in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases.

- William Lawrence Bragg (awarded Nobel prize in 1915), for his services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays.

- Niels Bohr (awarded Nobel prize in 1922), for his fundamental contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics.

- Charles Thomson Rees (C. T. R.) Wilson (awarded Nobel prize in 1927), for his method of making the paths of electrically charged particles visible by condensation of vapour.

- James Chadwick (awarded Nobel prize in 1935), for the discovery of the neutron.

- Patrick M. Blackett (awarded Nobel prize in 1948), for developing cloud chamber and confirming/discovering positron.

- Sir John Douglas Cockcroft (awarded Nobel prize in 1951), for his pioneer work on the splitting of atomic nuclei by artificially accelerated atomic particles and also for his contribution to modern nuclear power.

- Hans Bethe (awarded Nobel prize in 1967), for his contributions to the theory of nuclear reactions, especially his discoveries concerning the energy production in stars.

- Nevill Francis Mott (awarded Nobel prize in 1977), for his fundamental theoretical investigations of the electronic structure of magnetic and disordered systems.

- Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov (awarded Nobel prize in 2010), for groundbreaking experiments regarding the two-dimensional material graphene.[86]

Physiology and Medicine

- Archibald Vivian Hill (awarded Nobel prize in 1922), for his discovery relating to the production of heat in the muscle. One of the founders of the diverse disciplines of biophysics and operations research.

- Sir John Sulston (awarded Nobel prize in 2002), for his discoveries concerning 'genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death'. In 2007, Sulston was announced as Chair of the newly founded Institute for Science, Ethics and Innovation (iSEI) at the University of Manchester.[87]

Economics

- John Hicks (awarded Nobel prize in 1972), for his pioneering contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory.

- Sir Arthur Lewis (awarded Nobel prize in 1979), for his pioneering research into economic development research with particular consideration of the problems of developing countries.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz (awarded Nobel prize in 2001), for his analyses of markets with asymmetric information. Currently, Professor Joseph E. Stiglitz heads the Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) at the University of Manchester.

See also

Notes

- ^ The University of Manchester, Financial statements for the year ended 31 July 2009, p18. Manchester.ac.uk

- ^ a b c "Table 0a - All students by institution, mode of study, level of study, gender and domicile 2006/07" (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet). Higher Education Statistics Agency. http://www.hesa.ac.uk/dox/dataTables/studentsAndQualifiers/download/institution0607.xls. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ^ List of University of Manchester people List of University of Manchester people

- ^ "University of the Year". The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 2007-04-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20070410075916/http://www.manchester.ac.uk/international/news/universityoftheyear/. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ a b "Manchester unites to target world league". London: Sunday Times. 2006-09-10. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/education/student/news/article626449.ece. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ The University of Manchester is the largest single-site university in the United Kingdom. The Open University's total number of students exceeds that of Manchester but specialises primarily in correspondence courses and distant learning programmes, while Leeds Metropolitan University (which is based on two campuses), Hesa.ac.uk and University of London (which is more a collection of separate institutions) are not single-site institutions. News.BBC.co.uk "Largest single site university".

- ^ "Wealth and Health: Financial data for UK higher education institutions, 2009-10". Times Higher Education. 7 April 2011. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=26&storycode=415728&c=2. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Finances". The University of Manchester. http://www.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/governance/accounts2007.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ The RAE is undertaken every 5 to 7 years on behalf of UK's higher education funding councils and is the determining measure for governmental funding allocation in the country's higher education sector.Research Assessment Exercise

- ^ a b "RAE 2008: The results". Times Higher Education. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=404786. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2011.html

- ^ a b "History and Origins". The University of Manchester. http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/facts/history/. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ Charlton, H. B. (1951). Portrait of a university, 1851-1951. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. pp. x, 185.

- ^ "Leading economist joins Manchester Business School". Manchester Business School. http://www.mbs.ac.uk/newsevents/16-07-2007.aspx?rssNE. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Page, Benedicte (2011-01-26). "Colm Tóibín takes over teaching job from Martin Amis". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/jan/26/colm-toibin-teaching-martin-amis.

- ^ "President and Vice-Chancellor to retire". University of Manchester. 2010. http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=5362. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ "Towards 2015". The University of Manchester. http://www.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/2015/2015strategy.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ "Campus Map".

- ^ Manchester New Technology Institute. "Locations--One Central Park". http://www.manchesternti.com/about/one-central.htm. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Manchester Evening News 31 July 2007 "Cash-strapped uni sells assets". http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/business/s/1012/1012479_cashstrapped_uni_sells_assets.html. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ a b SCONUL Annual Library Statistics; 2005-2006

- ^ "Manchester Museum's Our collection page". http://www.museum.manchester.ac.uk/collection/. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ The History of The Manchester Museum, University of Manchester. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ "A Short History of The Whitworth Art Gallery". http://www.whitworth.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/history/. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ Hartwell, C. (2001) Manchester. London: Penguin (reissued: New Haven: Yale U. P.); p. 311-12

- ^ "Whitworth Park Halls of Residence". http://www.accommodation.manchester.ac.uk/ouraccommodation/areaguide/city/whitworthpark/.

- ^ Charlton, H. B.(1951) Portrait of a University. Manchester: U. P.; pp. 168-69

- ^ a b "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2011". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2011.html. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ a b "QS World University Rankings 2011/12". Quacquarelli Symonds. http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Top European Universities 2011". Times Higher Education. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2011-2012/europe.html. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "University League Table 2012". The Complete University Guide. http://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/league-tables/rankings. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "University guide 2012: University league table". The Guardian. 17 May 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2011/may/17/university-league-table-2012. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "The Sunday Times University Guide 2012". Times Newspapers. http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/. Retrieved 18 September 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ "The Times Good University Guide 2012". Times Newspapers. http://extras.thetimes.co.uk/public/good_university_guide_landing?CMP=KNGvccp1-the+times+university+rankings. Retrieved 17 September 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ http://www.suttontrust.com/research/innovative-university-admissions-worldwide/innovativeadmissions09.pdf

- ^ "RAE 2008: results for UK universities | Education | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. 2008-12-18. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2008/dec/18/rae-2008-results-uk-universities. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "Hefce university funding tables for 2009-10 | Education | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. 2009-03-05. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2009/mar/05/university-funding-research-england-table. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "Golden diamond outshines rest". Times Higher Education. 2004-07-23. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=190219. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "List Organisations". Gow.epsrc.ac.uk. 2010-11-19. http://gow.epsrc.ac.uk/ListOrganisations.aspx?Mode=Inst&Order=INA. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "Medical Research Council - Recipients of funding". Mrc.ac.uk. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Fundingopportunities/Applicanthandbook/Successrates/Recipientsoffunding/index.htm. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ External Relations (2009-08-17). "Top funded universities". BBSRC. http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk/organisation/spending/universities.aspx. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "Guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. 2008-08-05. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2008/aug/05/universityfunding.highereducation. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/Journals/THE/THE/17_March_2011/attachments/Total%20funding%20part%202.pdf

- ^ "Two University of Manchester discoveries in the top ten of all time (The University of Manchester)". Manchester.ac.uk. http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=5857. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "Manchester: Britain's greatest university? - Education News, Education". London: The Independent. 2010-10-09. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/manchester-britains-greatest-university-2101828.html. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "World University Rankings". The Times Higher Education Supplement. 2009. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/hybrid.asp?typeCode=438. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ "Topuniversities.com". Topuniversities.com. 2009-11-12. http://topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2008/indicator-rankings/employer-review. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2011

- ^ "Top 500 World Universities". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20080822124503/http://www.arwu.org/rank2008/EN2008.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Top 500 World Universities". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2009. http://www.arwu.org/ARWU2009.jsp. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Top 500 World Universities". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2009. http://www.arwu.org/ARWU2010.jsp. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ^ "ARWU FIELD 2009 Natural Sciences and Mathematics". Arwu.org. http://www.arwu.org/FieldSCI2009.jsp. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "ARWU FIELD 2009 Engineering/Technology and Computer Sciences". Arwu.org. http://www.arwu.org/FieldENG2009.jsp. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "2009 by fields Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities". Ranking.heeact.edu.tw. http://ranking.heeact.edu.tw/en-us/2009%20by%20Fields/Domain/ENG/Continent/Europe. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "2009 by fields Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities". Ranking.heeact.edu.tw. http://ranking.heeact.edu.tw/en-us/2009%20by%20Fields/Domain/SCI/Continent/Europe. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "2009 by fields Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities". Ranking.heeact.edu.tw. http://ranking.heeact.edu.tw/en-us/2009%20by%20Fields/Domain/SOC/Continent/Europe. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "THES - QS World University Rankings 2009 - Engineering/Technology". Top Universities. 2009-11-12. http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2009/subject-rankings/technology. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "THES - QS World University Rankings 2009 - Life Sciences & Biomedicine". Top Universities. 2009-11-12. http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2009/subject-rankings/life-sciences-bio-medicine. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "THES - QS World University Rankings 2009 - Social Sciences". Top Universities. 2009-11-12. http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2009/subject-rankings/social-sciences. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ http://www.psychol.cam.ac.uk/pages/the_top.pdf

- ^ http://www.scimagoir.com/pdf/sir_2009_world_report.pdf

- ^ "World University Rankings | Results for 2010". High Impact Universities. http://www.highimpactuniversities.com/rpi.html. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany. "Choose a university | Excellence Ranking - ZEIT ONLINE". Excellence Ranking. http://www.excellenceranking.org/eusid/EUSID?module=Hochschule&do=entry. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ http://rankings.ft.com/businessschoolrankings/manchester-business-school/global-mba-rankings-2011#global-mba-rankings-2011

- ^ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2011-2012/top-400.html#score_RI%7Csort_ind%7Creverse_false

- ^ "Most wanted students". The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 2007-04-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20070422002147/http://www.manchester.ac.uk/international/news/students/. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ "Highfliers.co.cuk" (PDF). http://www.highfliers.co.uk/download/GraduateMarket09.pdf. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ (French) Mines-paristech.fr

- ^ "Top Colleges & Universities in the UK | University Web Rankings". 4icu.org. http://www.4icu.org/gb/. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "List of the 20 Best Non-U.S. Universities and Colleges in the World". Education-portal.com. 2008-07-14. http://education-portal.com/articles/List_of_the_20_Best_Non-US_Universities_and_Colleges_in_the_World.html. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/hybrid.asp?typeCode=494&pubCode=1&navcode=157

- ^ The Guardian (London). http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Education/documents/2009/08/20/ReputationRankings2009in.pdf.

- ^ http://www.topuniversities.com/scorecard?f=1®ion=Europe&overall_academic_reputation=1&overall_employer_reputation=1&overall_international_faculty_ratio=0&overall_international_student_ratio=0&overall_citations_per_faculty=0&overall_faculty_student_ratio=0

- ^ "2008 Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities". Ranking.heeact.edu.tw. http://ranking.heeact.edu.tw/en-us/2008/Continent/Europe. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ^ "The Times Good University Guide 2011 - Times Online location=London". http://extras.thetimes.co.uk/gooduniversityguide/institutions/.

- ^ "The Complete University Guide League Table 2012 - Higher, Education". London: The Complete University Guide. 2011. http://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/league-tables/rankings. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ "University guide 2012: University league table | Education | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. 2011-05-17. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2011/may/17/university-league-table-2012. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ "Manchester University Boat Club". Mubc.org.uk. 2010-11-25. http://www.mubc.org.uk/. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "Battle of the North". http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/index.htm?id=133663. Retrieved 2008-04-03.[dead link]

- ^ "Championships". BUSA. http://www.busa.org.uk/page.asp?section=00010001000200010005&itemTitle=Championships. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "School of Medicine". The University of Manchester. http://www.medicine.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ^ "School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (University of Manchester)". Pharmacy.manchester.ac.uk. http://www.pharmacy.manchester.ac.uk/. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ^ "School of Pharmacy". The University of Manchester. http://www.pharmacy.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/history/. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ^ "Manchester Academic Health Science Centre". http://www.mahsc.ac.uk/. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Linton, Deborah (9 July 2011). "Revealed: Sporting mecca at the heart of Etihad's record sponsorship of Manchester City". Manchester Evening News. http://menmedia.co.uk/manchestereveningnews/news/s/1426249_revealed-sporting-mecca-at-the-heart-of-etihads-record-sponsorship-of-manchester-city. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010 Andre Geim, Konstantin Novoselov". Nobel Foundation. 2010-10-05. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2010/press.html#. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ^ "Nobel Prize Winner to Chair New Institute". The University of Manchester - UniLife. http://www.staffnet.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/unilife/vol5-issue2.pdf. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

External links

- "Official page of the University of Manchester". http://www.manchester.ac.uk.

- "Official page of the University of Manchester Incubator Company/UMIC". http://www.umic.co.uk.

- "Official page of the University of Manchester Intellectual Property/UMIP". http://www.umip.com.

Links to related articles Universities and colleges in North West England Universities Bolton · Central Lancashire · Chester · Cumbria · Edge Hill · Lancaster · Liverpool · Liverpool Hope · Liverpool John Moores · Manchester · Manchester Metropolitan · SalfordUniversity colleges Further Education colleges Accrington & Rossendale · Blackburn · Blackpool & The Fylde · Bolton · Burnley · Bury · Carlisle · Furness · Hopwood Hall · Hugh Baird · Kendal · Knowsley · Lakes · Lancaster & Morecambe · Liverpool · Macclesfield · Manchester · Mid Cheshire · Myerscough · Nelson & Colne · Oldham · Preston · Reaseheath · Riverside · Runshaw · St Helens · Salford · South Cheshire · Southport · Stockport · Tameside · Trafford · Warrington · West Cheshire · West Lancashire · Wigan & Leigh · Wirral MetropolitanSixth form colleges Aquinas · Ashton · Barrow-in-Furness · Birkenhead · Blackpool · Bolton · Cardinal Newman · Carmel · Cheadle & Marple · Holy Cross · Hyde Clarendon · King George V · Loreto · Oldham · Priestley · Rainford · Roby · Rochdale · Sir John Deane's · St John Rigby · St Mary's · Thomas Whitham · Winstanley · Xaverian Universities in the United Kingdom

Universities in the United KingdomEngland LondonBirkbeck · CSSD · Courtauld · Goldsmiths · Heythrop · ICR · IoE · King's · LBS · LSE · LSHTM · Queen Mary · Royal Academy of Music · Royal Holloway · RVC · St George's · SOAS · School of Pharmacy · UCLOtherBrunel · City · East London · Greenwich · Kingston · Imperial · London Met · London South Bank · Middlesex · RCA · Roehampton · UAL · Westminster · West LondonMidlandsAston · Birmingham · Birmingham City · Coventry · De Montfort · Derby · Keele · Leicester · Lincoln · Loughborough · Northampton · Nottingham · Nottingham Trent · Staffordshire · Warwick · Wolverhampton · WorcesterNorthBolton · Bradford · Central Lancashire · Chester · Cumbria · Durham · Edge Hill · Huddersfield · Hull · Lancaster · Leeds · Leeds Metropolitan · Liverpool · Liverpool Hope · Liverpool John Moores · Manchester · Manchester Metropolitan · Newcastle · Northumbria · Salford · Sheffield · Sheffield Hallam · Sunderland · Teesside · York · York St. JohnSouthAnglia Ruskin · Bath · Bath Spa · Bedfordshire · Bournemouth · Brighton · Bristol · Buckingham · Buckinghamshire New · Cambridge · Canterbury Christ Church · Chichester · Cranfield · Creative Arts · East Anglia · Essex · Exeter · Gloucestershire · Hertfordshire · Kent · Oxford · Oxford Brookes · Plymouth · Portsmouth · Reading · Southampton · Southampton Solent · Surrey · Sussex · UWE · WinchesterNorthern Ireland Scotland Aberdeen · Abertay Dundee · Dundee · Edinburgh · Edinburgh Napier · Glasgow · Glasgow Caledonian · Heriot-Watt · Highlands and Islands · Queen Margaret · Robert Gordon · RCS · St Andrews · Stirling · Strathclyde · UWSWales Aberystwyth · Bangor · Cardiff · Cardiff Metropolitan · Glamorgan · Glyndŵr · Newport · Swansea · Swansea Metropolitan · Trinity Saint DavidNon−geographic University colleges Birmingham · Bishop Grosseteste Lincoln · Bournemouth · BPP · Falmouth · Harper Adams · Leeds Trinity · NCH · Newman · Norwich · Plymouth St Mark & St John · St. Mary's (Belfast) · St. Mary's (Twickenham) · Stranmillis · SuffolkUniversity centres Related  Category ·

Category ·  Commons ·

Commons ·  List

ListRussell Group of UK research universities Birmingham · Bristol · Cambridge · Cardiff · Edinburgh · Glasgow · Imperial College London · King's College London · Leeds · Liverpool · London School of Economics · Manchester · Newcastle · Nottingham · Oxford · Queen's · Sheffield · Southampton · University College London · WarwickCategories:- Buildings and structures in Manchester

- Education in Manchester

- University of Manchester

- Educational institutions established in 2004

- Russell Group

- Association of Commonwealth Universities

- 2004 establishments in England

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.