- Diprotodon

-

Diprotodon

Temporal range: Pleistocene

Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Infraclass: Marsupialia Order: Diprotodontia Suborder: Vombatiformes Family: †Diprotodontidae Genus: †Diprotodon

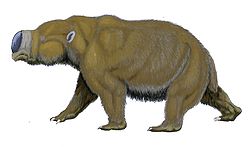

Owen, 1838Species: †D. optatum Binomial name Diprotodon optatum Diprotodon, meaning "two forward teeth",[1] sometimes known as the Giant Wombat or the Rhinoceros Wombat, was the largest known marsupial that ever lived. Along with many other members of a group of unusual species collectively called the "Australian megafauna", it existed from approximately 1.6 million years ago until extinction some 46,000 years ago[2] (through most of the Pleistocene epoch).

Diprotodon species fossils have been found in sites across mainland Australia, including complete skulls and skeletons, as well as hair and foot impressions.[1] Female skeletons have been found with babies located where the mother's pouch would have been.[1] The largest specimens were hippopotamus-sized: about 3 metres (9.8 ft) from nose to tail, standing 2 metres (6.6 ft) tall at the shoulder and weighing up to 2,786 kilograms (6,140 lb).[3][4] They inhabited open forest, woodlands, and grasslands, possibly staying close to water, and eating leaves, shrubs, and some grasses.

The closest surviving relatives of Diprotodon are the wombats and the koala. It is suggested that diprotodonts may have been an inspiration for the legends of the bunyip, as some Aboriginal tribes identify Diprotodon bones as those of "bunyips".[5]

Contents

Discovery

The first recorded Diprotodon remains were discovered in a cave near Wellington in New South Wales in the early 1830s by Major Thomas Mitchell who sent them to England for study by Sir Richard Owen. In the 1840s Ludwig Leichhardt discovered many Diprotodon bones eroding from the banks of creeks in the Darling Downs of Queensland and when reporting the find to Owens commented that the remains were so well preserved he expected to find living examples in the then unexplored central regions of Australia.

The majority of fossil finds are of demographic groups indicative of diprotodonts dying in drought conditions. For example, hundreds of individuals were found in Lake Callabonna with well preserved lower bodies but crushed and distorted heads.[6] It is theorised several family groups sank in mud while crossing the drying lake bed. Other finds consist of age groupings of young or old animals which are first to die during a drought.

Taxonomy

Diprotodon was named by Owen (1838). It was assigned to Diprotodontidae by McKenna and Bell (1997). The historical classification of Diprotodon consisted of eight species (Diprotodon optatum Owen, 1838; Diprotodon australis Owen, 1844; D. annextans McCoy, 1861; D. minor Huxley, 1862; D. longiceps McCoy 1865; D. loderi Krefft, 1873a; D. bennettii Krefft, 1873b (nec D. bennettii Owen, 1877); and D. bennettii Owen, 1877 (nec D. bennettii Krefft, 1873b); based on size or slight morphological differences of single specimens collected from isolated geographic regions.[6] Bimodal dental sizes, rather than a continuum of tooth sizes, and identical male and female dental morphology, indicate sexual dimorphism instead of separate species, thus providing strong evidence that the eight species are synonyms for D. optatum.[6]

Morphology

Diprotodon superficially resembled a rhinoceros without a horn. Its feet turned inwards like a wombat’s, giving it a pigeon-toed appearance. It had strong claws on the front feet and its pouch opening faced backwards. Footprints of its feet have been found showing a covering of hair which indicates it had a coat similar to a modern wombat.

Until recently it was unknown how many species of Diprotodon had existed. Eight species are described although many researchers believed these actually represented only three at most while some estimated there could be around twenty in total.

Recent research compared the variation between all of the described Diprotodon species with the variation in one of Australia’s largest living marsupials the Eastern Grey Kangaroo and found the range was comparable, with a near continent-wide distribution.[6] This left only two possible Diprotodon species differing only in size with the smaller being around half the size of the larger. According to Gause’s “competitive exclusion principle” no two species with identical ecological requirements can coexist in a stable environment. However, both the small and large diprotodonts coexisted throughout the Pleistocene and the size difference is similar to other sexually dimorphic living marsupials. Further evidence is the battle damage common in competing males found on the larger specimens but absent from the smaller. Dental morphology also supports sexual dimorphism, with highly sexually dimorphic marsupials, such as the grey kangaroo, having different tooth sizes between males and females, but both sexes having the same dental morphology. An identical dental morphology occurs in the large and small Diprotodon.[6] The taxonomic implication is that Owen’s original Diprotodon optatum is the only valid species.

A single sexually dimorphic species allows behavioral interpretations. All sexually dimorphic species of over 5 kg in weight exhibit a polygynous breeding strategy. A modern example of this is the gender segregation of elephants where females and the young form family groups while lone males fight for the right to mate with all the females of the group. This behavior is consistent with fossil finds where adult/juvenile fossil assemblages usually contain only female adult remains.[7][8]

Date of extinction

Most modern researchers including Richard Roberts and Tim Flannery argue that diprotodonts, along with a wide range of other Australian megafauna, became extinct shortly after humans arrived in Australia about 50,000 years ago.[2]

Some older researchers including Richard Wright argue on the contrary that diprotodont remains from several sites, such as Tambar Springs[9] and Trinkey and Lime Springs[10][11] suggest that Diprotodon survived much longer, into the Holocene. Other more recent researchers, including Lesley Head and Judith Field, favor an extinction date of 28 000 - 30 000 years ago, which would mean that humans coexisted with Diprotodon for some 20 000 years.[12] However, opponents of "late extinction" theories have interpreted such late dates based on indirect dating methods as artifacts resulting from redeposition of skeletal material into more recent strata,[2][13] and recent direct dating results obtained with new technologies have tended to confirm this interpretation.[14][15]

Cause(s) of extinction

Three theories have been advanced to explain the mass extinction.

Climate change

Australia has undergone a very long process of gradual aridification since it split off from Gondwanaland about 40 million years ago. From time to time the process reversed for a period, but overall the trend has been strongly toward lower rainfall. The recent ice ages produced no significant glaciation in mainland Australia but long periods of cold and very dry weather. This dry weather during the last ice age may have killed off all the large diprotodonts.

Critics point out a number of problems with this theory. First, large diprotodonts had already survived a long series of similar ice ages, and there does not seem to be any particular reason why the most recent one should have achieved what all the previous ice ages had failed to do. Also, climate change apparently peaked 25,000 years after the extinctions. Finally, even during climatic extremes, some parts of the continent always remain relatively exempt: for example, the tropical north stays fairly warm and wet in all climatic circumstances; alpine valleys are less affected by drought, and so on.

Human hunting

Cast of a Diprotodon skeleton at Queensland Museum.

Cast of a Diprotodon skeleton at Queensland Museum.

The "blitzkrieg theory" is that human hunters killed and ate the diprotodonts, causing their extinction. The extinctions appear to have coincided with the arrival of humans on the continent, and in broad terms, Diprotodon was the largest and least well-defended species that died out. Also, similar hunting-out happened with the megafauna of New Zealand, Madagascar and many smaller islands around the world (such as New Caledonia, Cyprus, Crete and Wrangel Island), and at least in part, in the Americas—probably within a thousand years or so. Recent finds of Diprotodon bones which appear to display butchering marks lend support to this theory. Critics of this theory regard it as simplistic, arguing that (unlike New Zealand and America) there is little direct evidence of hunting, and that the dates on which the theory rests are too uncertain to be relied on.

Human land management

The third theory says that humans indirectly caused the extinction of diprotodonts, by destroying the ecosystem on which they depended. In particular, early Aborigines are thought to have been fire-stick farmers using fire regularly and persistently to drive game, open up dense thickets of vegetation, and create fresh green regrowth for both humans and game animals to eat. Evidence for the fire hypothesis is the sudden increase in widespread ash deposits at the time that people arrived in Australia, as well as land-management and hunting practices of modern Aboriginal people as recorded by the earliest European settlers before Aboriginal society was devastated by European contact and disease. Evidence against the hypothesis is the fact that humans appear to have eliminated the megafauna of Tasmania without using fire to modify the environment there.[16][17][18]

Multiple causes

The above hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Each of proposed mechanisms can potentially support the other two. For example, while burning an area of fairly thick forest and thus turning it into a more open, grassy environment might reduce the viability of a large browser (an animal that eats leaves and shoots rather than grasses), the reverse could also be true: removing the browsing animals (by eating them, or by any other means) within a few years produces a very thick undergrowth which, when a fire eventually starts through natural causes (as fires tend to do every few hundred years), burns with greater than usual ferocity. The burnt-out area is then repopulated with a greater proportion of fire-loving plant species (notably eucalypts, some acacias, and most of the native grasses) which are unsuitable habitat for most browsing animals. Either way, the trend is toward the modern Australian environment of highly flammable open sclerophyllous forests, woodlands and grasslands, none of which are suitable for large, slow-moving browsing animals—and either way, the changed microclimate produces substantially less rainfall.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Science & Nature: Animals: Diprotodon". Official website. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). July 2008. http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/3040.shtml. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Roberts, R. G.; Flannery, T. F.; Ayliffe, L. K.; Yoshida, H.; Olley, J. M.; Prideaux, G. J.; Laslett, G. M.; Baynes, A.; Smith, M. A.; Jones, R.; Smith, B. L. (2001-06-08). "New Ages for the Last Australian Megafauna: Continent-Wide Extinction About 46,000 Years Ago". Science 292 (5523): 1888–1892. doi:10.1126/science.1060264. http://www.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@sci/@eesc/documents/doc/uow014698.pdf. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Ice Age Marsupial Topped Three Tons, Scientists Say, 2003-09-17. Retrieved 2003-09-17.

- ^ 2,786 kg is the estimation for the specimen displayed in the Australian Museum which is considered to be of average size. According to latest research the average male weight is estimated to lie between 2,272 kg and 3,417 kg.

- ^ Shuker, Karl P. N. (1995). "5". In search of prehistoric animals; Do giant extinct creatures still exist? (1 ed.). Blanchford. ISBN 0713724692. "As far back as 1924, Dr C.W. Anderson of the Australian Museum had suggested that stories of the bunyip could derive from aboriginal legends of the extinct diprotodonts — a view repeated much more recently in Kadimakara (1985) by Australian zoologists Drs. Tim Flannery and Michael Archer, who nominated the palorchestids as plausible candidates."

- ^ a b c d e Price, G. J. (August 2006). "Taxonomy and palaeobiology of the largest-ever marsupial, Diprotodon Owen, 1838 (Diprotodontidae, Marsupialia)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 153 (2): 369–397. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00387.x.

- ^ Sex secrets of a prehistoric marsupial Cosmos Magazine June 11, 2008

- ^ Australian Science Magazine June 2008 Pleistocene Goliath; Gilbert Price

- ^ Richard Wright (1986). New light on the extinction of the Australian magafauna.

- ^ James Cohen (1995). Aboriginal environmental impacts.

- ^ Sunda and Sahul: Prehistoric Studies in Southeast Asia, Melanesia and Australia. London: Academic Press. 1977. pp. 205–246.

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/science/future/theses/theses1.htm

- ^ Flannery, Tim (2002-10-16). The future eaters: an ecological history of the Australasian lands and people. New York: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.. ISBN 0802139434. OCLC 32745413. http://google.com/books?id=eIW5aktgo0IC&printsec=frontcover.

- ^ Jones, C. (2010-01-23). "Early humans wiped out Australia's giants". Nature News web site. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/news.2010.30. http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100123/full/news.2010.30.html. Retrieved 20112-11-07.

- ^ Grün, R.; Eggins, S.; Aubert, M.; Spooner, N.; Pike, A. W. G.; Müller, W. (2010-03). "ESR and U-series analyses of faunal material from Cuddie Springs, NSW, Australia: implications for the timing of the extinction of the Australian megafauna". Quaternary Science Reviews 29 (5-6): 596–610. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.11.004. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379109003679. Retrieved 20112-11-07.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2008-08-13). "Palaeontology: The last giant kangaroo". Nature 454 (7206): 835–836. doi:10.1038/454835a. PMID 18704074. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v454/n7206/full/454835a.html. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ Turney, C. S. M.; Flannery, T. F.; Roberts, R. G.; et al. (2008-08-21). "Late-surviving megafauna in Tasmania, Australia, implicate human involvement in their extinction". PNAS (NAS) 105 (34): 12150–12153. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801360105. PMC 2527880. PMID 18719103. http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2008/08/20/0801360105.abstract. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ Roberts, R.; Jacobs, Z. (2008-10). "The Lost Giants of Tasmania". Australasian Science 29 (9): 14–17. http://www.control.com.au/bi2008/299megafauna.pdf. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- Danielle Clode (2009) Prehistoric giants: the megafauna of Australia. Museum Victoria.

- Barry Cox, Colin Harrison, R.J.G. Savage, and Brian Gardiner. (1999): The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Jayne Parsons.(2001): Dinosaur Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley.

- David Norman. (2001): The Big Book Of Dinosaurs. Welcome Books.

- Gilbert Price. (2005): Article in Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. Queensland Museum.

- http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/bunyip.htm on bunyip theories

External links

Categories:- Prehistoric vombatiforms

- Pleistocene mammals

- Pleistocene extinctions

- Prehistoric mammals of Australia

- Megafauna of Australia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.