- Mazawattee Tea Company

-

The Mazawattee Tea Company, founded by the Densham family, was one of the most important and most advertised tea firms in England during the late 19th century. Traditionally the origin of tea-drinking lies in China and the famous Tea Clipper ships raced across the seas to bring tea to London. In the 18th century, tea had become an important drink in Britain especially for the wealthy, but it was not until the 1850s (by which time tea plantations had been successfully established in India, especially in Assam, and in Ceylon) that a real expansion occurred. The Densham family were at the forefront of this period of growth. Originally from Plymouth, they moved to London and managed to amass a fortune from the business in quite a short time. The Denshams later owned fine properties in both Purley and Croydon and one of the founder’s sons, Edward, became a well-known figure in Purley.

The growth of tea drinking and the rise of the Densham family

In Britain in the early days, tea drinking was very much a social occasion; tea was widely drunk in tea gardens in London, perhaps best exemplified by a contemporary short ditty:

Bon Ton’s the space ’twixt Saturday and Monday,

’Tis riding in a one horse chair on Sunday,

’Tis drinking tea on summer afternoons

At Bagnigge Wells with china and gilt spoons.1Tea imports to Britain rose from 30 million pounds a year in the 1830s to 80 million pounds in the 1860s and 200 million pounds in the 1890s. Companies such as Twinings grew apace and new firms such as Hornimans began to trade around 1840. It was not long before John Boon Densham came to London. He had been a chemist and druggist in Plymouth when such shops also blended and sold teas. Tea was widely advocated by the Temperance movement to counteract alcohol consumption and Densham, being a strict Baptist, was probably influenced by this aspect. He set up as a wholesaler in 1865 and then moved to London in his 50s and started trading exclusively in wholesale tea. The first name of the firm was Lees & Densham but by 1873 it became Densham & Sons, owned by Densham (then aged nearly 60) and his three eldest sons, Edward, Alfred, and Benjamin who were then in their late 20s or early 30s. Edward later took over the main role.

The firm grew without major changes but things altered when the youngest son, John Lane Densham, then in his late 20s, joined as an employee in 1881. He had not been able to devote himself to daily labour previously owing to poor health but once he joined he soon became the leading light; he was an indefatigable traveller for the firm and his brothers were soon able to rely on his efforts.

A simple innovation that would later change the whole retail tea industry had been introduced in 1826 by John Horniman, who hit on the idea of packaging tea so that customers could buy a reliable and known brand with confidence and not have to rely on what the grocer selected from his tea-chests. A simple machine was soon devised to carry out the process more speedily and efficiently. Although packet tea took time to become popular, the Denshams realised that this was the way ahead for retail sales and offered their first packets of Ceylon tea in 1884. By then, other firms such as the Co-operative Wholesale Society (1863), Brooke Bond (1869) and Liptons (1888) had entered the field, although it was not until the early 1900s that packet tea sales outstripped those of loose tea.

The origin of Mazawattee tea and the expansion of the firm

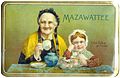

The death of John Boon Densham at the age of 72 at his home in Croydon in 1886 ended the first period of the firm’s growth. John Lane Densham was immediately made a partner and tackled the problem of the firm. He decided to supply its tea in packets to retailers and in a different way by inventing a name for the firm. Being a great advocate of advertising, he reckoned that something quite unusual might be the answer and went to the Guildhall Library to get ideas. He came up with the idea of using the word “Mazathawattee”, perhaps based on the Hindi “Mazaa”, which means "pleasure or fun," and the Sinhalese “vatta," which means "a garden." This was shortened to “Mazawattee” and duly registered as a trade mark for retail sales in May 1887. This was merely a start for he then had the idea of using a standard picture to advertise the brand. It is to many modern eyes a rather gloomy thing showing an aged, bespectacled and somewhat toothless grandmother with her supposed granddaughter and the compulsory cup of tea. This picture became popular and was used in its original form for many years. Although the artist is not known, the model for the grandmother was Mary Ann Clarke, the wife of an Islington bootmaker. The model for the child was to have been her granddaughter but she was too shy, and the artist had to enlist the aid of the little girl next door, Alice Emma Nichols. The picture was called “Old Folks at Home”.

It was not long before the firm’s name was everywhere, stressing the quality of Mazawattee to counteract the criticism of “doctoring” that had been levelled at some teas. A contract was made with the railway companies so that eye-catching enamelled signs could be fixed on every railway station platform in Britain. Ceylon tea had been introduced to Britain in 1875 and Mazawattee concentrated for some years on this type of tea and at one time named itself the Mazawattee Ceylon Tea Company. High prices were obtained by dealers, especially for the hand-selected leaf buds of good quality tea known as “Golden Tips”. By 1891 this bubble burst and normality returned.

Although the parent company of Densham & Sons handled the loose tea trade from 49/51 Eastcheap, by 1894 Mazawattee had its own offices together with warehouses and vaults in a large building erected at the top of Tower Hill, very near the Tower of London. This was so tall that it blocked the view to the east from the adjacent church of All Hallows by the Tower, not to the liking of the church authorities.2. The Mazawattee building was a perfect venue for viewing big events such as the opening of Tower Bridge on 30 June 1894.

In May 1896 the firm became a public limited company, the Mazawattee Tea Company Ltd, which acquired the Mazawattee Ceylon Tea Company and Densham & Sons (the wholesale tea and coffee dealing part of he business). The capital was £550,000 (= £21,400,000 in 2009 terms) in 5% cumulative preference shares of £5 each and 350,000 ordinary shares of £1 each (= £13,625,000 in 2009 terms). The four brothers received 13,333 preference shares and 116,666 ordinary shares, a total of £183,333 (= £7,136,000 in 2009 terms). The remainder of the 26,667 preference shares and 233,334 ordinary shares were offered for sale. As part of this arrangement and so that the two oldest brothers, Edward and Alfred could retire early, £30,000 each (= £1,167,000 in current terms) was paid to John Lane and Benjamin, and John Lane Densham soon became chairman.

Problems after 1900

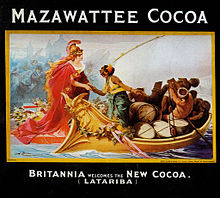

After 1900 things started to go wrong. Tea prices rose, largely due to an increase in duty to help meet the cost of the Boer War (1899–1902) and there were strikes and political troubles. Not to be deterred, John Lane Densham kept travelling round the world on behalf of the firm, often taking his family with him, but marred by health problems. He had many interviews with representatives, discussions with agents and visited tea estates in India and Ceylon. Nevertheless, sales began to drop and a scheme was devised to branch out into the cocoa and chocolate trade. This was a risky step to take. A huge site was acquired near New Cross alongside the Surrey Union Canal and a vast building constructed to process and pack products and opened in 1901. The inaugural luncheon was reported favourably in the press for this was a factory built on a grand scale: at one time nearly 2,000 people worked there. For the most part single-storey, it was designed in an impressive and efficient way with a central service corridor. There was a separate tin-making and tin-printing department. Once again, the future looked encouraging. Publicity continued as ever and typical of the inventiveness of the firm was a small round coin-like commemorative tin containing a chocolate distributed in 1902 to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII. These may have been given to children as local souvenirs for some of them that have survived have the name of a town added at the bottom of the lid. Another splendid memento of this event was a booklet designed by William Theodore Parkes illustrating the National Anthem with the words and music embellished with ornate emblematic designs; Parkes had started his career in Ireland and exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy from 1880 to 1883, after which he worked in London. The booklet is a fine example of period art, selling for one shilling, linking tea with royalty. Many other fine tins were produced in these years, often celebrating events, and also for other firms. Mazawattee produced other things under various names, such as spices and cake flavourings - even a hair tonic.

It was not long before more problems arose; sales declined and the trade in cocoa was not as great as expected. In 1902, John Lane’s health deteriorated and he was obliged to hand over the managing directorship to Robert McQuitty and Alexander Jackson and go abroad. His time was not wasted, for he started to arrange for tea to be sent direct from the estates to Russia, America and British Colonies. Events at home almost led to the complete downfall of the Mazawattee business: McQuitty and another director, John McClean, started a major change in policy, possibly trying to emulate other tea merchants that had also become successful retailers: they persuaded John Lane’s brother Benjamin that the way ahead was to open Mazawattee retail shops. They lost no time began to open café-type saloons selling packet tea as a sideline. There was no proper control and they went ahead in a kind of frenzy. They were splendid places with colourful tiles and plenty of mahogany fitments - £10,000 was absorbed by one shop alone (about £400,000 in 2009 terms). As part of the scheme many staff at head office were dismissed including Alexander Jackson. Being close to old-established grocery shops, these new shops created opposition, and it was not long before an urgent plea was sent to John Lane Densham beseeching him to return home to rectify the situation. He called an urgent general meeting in March 1906, sacking the two managing directors. Benjamin Densham resigned as chairman and subsequently it was found that McQuitty and McClean had played upon his weakness not helped by his addiction to secret drinking and had used this to get his support for their schemes. A year later Benjamin was dismissed, being incapable of transacting business in a proper manner.

That same year expenditure on special advertising was agreed. Some most attractive advertising products were issued from then onwards and there was a proliferation of fine things including calendars, diaries, atlases, dictionaries, and tins, many of these designed by artists of repute. There was even a small game, “Our Kings and Queens”, 38 cards produced in fine lithographic printing, a variation of “Happy Families”, the idea being to complete the “trick” of monarchs in each century. Many of these items are now much sought after by collectors.

Decline after 1918

After World War I the tea tax was increased. John Lane Densham resigned the chairmanship in 1915 as his health had been failing for some time and he died whilst abroad on 13 February 1918, the firm losing one of its main assets. Alexander Jackson took over as chairman and many amusing advertisements were still devised including the idea of using a small team of tame zebras to haul one of the Mazawattee vans, notably in the Tunbridge Wells area. When he died in 1933 Joseph Alexander Densham (his eldest son) became chairman but it was not long before the confectionery department had to be shut down, in 1936. World War II caused terrible destruction to the firm: in late 1940 the Tower Hill building was bombed and wrecked, and the New Cross factory was heavily bombed and largely destroyed. The business struggled on under Joseph Alexander Densham until he retired in 1953. It was then sold to a subsidiary of Burton, Son & Sanders Ltd, possibly as a tax-loss company. The Mazawattee name was used for a while although the tea was packed by one of the big tea firms, but that arrangement soon ended; the days of Mazawattee were over.

The Densham family and homes in Croydon and Purley

When John Boon Densham (1814–1886) came to London from Plymouth, he may have lived in the Forest Hill area; in later years, perhaps when he had retired, he moved to Croydon where his sons already lived. He lived at “Ferny Bank”, Hurst Road in the late 1870s and then moved to “Mannamead”, Birdhurst Road (now no.17) around 1881. He died there on 3 December 1886 aged 72 and was buried at St John the Evangelist Church, Old Coulsdon on 8 December; his grave and that of his wife, who had predeceased him (together with that of his eldest son Edward and his wife) is to the west of the church.

Edward, who ran the firm for many years before the advent of the Mazawattee name, lived in Purley, initially at “Olden Lodge” in Olden Lane but in 1885 he bought a grand house, “Foxley”, at the Purley end of Higher Drive together with its large estate. In 1894 he was elected as an independent candidate to the new Croydon Rural District Council and was later Chairman for three years. He was also a J.P., being admired for his kindness, and also a member and Chairman of the Board of Guardians. In this capacity he was present when the Duchess of Albany declared the Purley Fountain (the Queen Victoria Memorial) open on Saturday 11 June 1904. He became a man of some prominence locally and supported the introduction of electricity to the Croydon area. Many of his sons were educated at Whitgift School. “Foxley” had extensive grounds and woodland with pleasant views and around 1907 Edward set about using some of the land along the Higher Drive edge for new homes for his offspring: “Foxley Lodge”, 2 Higher Drive (Arthur John); “Woodlands”, no. 31 (Edward D.); “Brackenhurst”, no. 65 (Frank); “The Warren”, no. 67 (H.J. “Jack”); and “Tresco”, no. 73 (George). Edward died on 30 April 1912 aged 69 and was buried in the same grave as his father and mother at Old Coulsdon. He left a gross estate of roughly £75,000 (£2,600,000 in 2009 terms).

Alfred Densham lived at “Dingwall Cottage”, Dingwall Road, Croydon and then moved slightly south to an area a number of the family soon settled in: St Peter’s Road near St Peter’s Church. In the 1870s he was at no. 2, “Southbourne Villas”. In the 1890s he moved to “Hurstleigh”, 23 South Park Hill Road and after his retirement in 1896 to “Foxley Lodge”, 2 Higher Drive, Purley. Benjamin Densham, like Alfred, lived in St Peter’s Road at “Britannia Villa” (now no. 46), then moved to “Homeside”, 26 Friends Road; “Sunnyside”, 45 Birdhurst Rise; and in the 1890s to “Minard”, 19 Chichester Road; then to “Bramley Croft”, Haling Park Road, a splendid house. After the problems of 1907, he relocated to Hindhead and became a yachtsman.

John Lane Densham, lived in Croydon, initially at “Springfield”, 7 Dingwall Road and in the 1890s he joined the others in St Peter’s Road, at “Deanfield”, No 51. Around 1896 he moved to the magnificent “Waldronhyrst,” 24 The Waldrons; this fine house, which was extended from time to time, needed a staff of ten to run it including its own coachman. In 1904 he was elected to the Borough Council for three years and was also a governor of Croydon General Hospital. His youngest son, Stephen Hugh, died in December 1917 at Étaples from wounds received near Arras and John Lane died due to para-typhoid at the age of 64 whilst at the home of a married daughter in Boksburg, South Africa.

Remaining traces of the firm’s premises and homes

The imposing building at Tower Hill is no more, owing to bombing, but the cellars remain as “Tower Vaults”, a small largely underground shopping area with restaurants and small shops used mainly by visitors to the Tower of London; in the centre of the floor is a fine circular bronze plaque commemorating the origin of the spot. The church of All Hallows by the Tower was also badly damaged in 1940 but was rebuilt later, so at last it has its original view to the east. At New Cross, the bombing was so bad that the factory was virtually wrecked yet some parts remain. The words “Elizabeth Industrial Estate” can be spotted from trains from New Cross Gate to London Bridge, just before the new Waste Transfer Station: these are on a smallish tower that was used as part of the factory boiler-system. The old Grand Surrey Canal is no more, having been filled in and is now Surrey Canal Road. At the entrance to the Elizabeth Estate are a number of remnants of the old Mazawattee factory, notably a corner building and part of the main entrance from the canal side.

Of John Boon Densham’s homes, only “Mannamead” remains, as 17 Birdhurst Road, South Croydon. Edward’s fine “Foxley” (later “Foxley Hall”) became flats and then a hotel before being demolished around 1968 and replaced by flats and houses that retain the name “Foxley Hall”. His sons’ string of houses in Higher Drive largely remain, well-maintained and fine properties. Only “Tresco” has gone, replaced by a cul-de-sac named Densham Drive. In the 1930s there was a proposal to develop the wooded area of the estate but there was a public outcry. This resulted in the purchase of 19 acres (7.688 hectares) by the Urban District Council in November 1937 and its registration under the Green Belt Scheme. Later Sherwood Oaks was added to this so that there is now one large area of public land.

Three of Alfred’s homes remain: 2 “Southbourne Villas” (now 15 St Peter‘s Road), “Hurstleigh”, 23 South Park Hill Road and “Foxley Lodge”, 2 Higher Drive, only the Dingwall Road house having been demolished. Of Benjamin’s homes, two have gone (26 Friends Road and “Minard”, 19 Chichester Road) but the others remain. “Bramley Croft”, Haling Park Road is now “St John’s Nursing Home”. The first of John Lane Densham’s houses in Dingwall Road has gone, but “Deanfield” is still there in St Peter’s Road (No 51); Waldronhyrst” became a residential hotel for many years as The Waldronhyrst Hotel, catering to visitors from the Indian subcontinent until the late 1950s. It was then used partly as flats but was demolished in the 1970s to make way for a new estate of houses and flats, adjacent to “The Waldrons” conservation area.

A few words by the poet William Cowper give a reminder of the perhaps more leisurely earlier days of tea drinking in the 18th century:

Now stir the fire, and close the shutters fast,

Let fall the curtains, wheel the sofa round,

And, while the bubbling and loud-hissing urn

Throws up a steamy column, and the cups

That cheer but not inebriate, wait on each,

So let us welcome peaceful ev’ning in.3Image gallery

Trivia

In the 1940 film Gaslight a horse-drawn bus can be seen displaying a large advertisement for Mazawattee Tea a few minutes into the film.

On 10 March 2010 The Mirror wrote an article on the oldest food found in people's homes. One of these mentioned was a 69 year old gas-proof tin of mazawattee tea. The tin has never been opened and belongs to a resident of Cowes in The Isle of Wight. An Image of the tea is shown above.

Notes

^1 none From the prologue by George Colman to David Garrick’s farce “Bon Ton, or High Life above Stairs”, 1775.

^2 none This church became the centre for “Toc H”. The original Toc H was a building in Poperinghe, Belgium where the Rev. Philip “Tubby” Clayton set up a rest centre for soldiers where they could have a break from the horrors of the war. Clayton became Vicar of All Hallows by the Tower in 1922 and soon used this as a base as a roving ambassador for Toc H. He lived nearby at 43 Trinity Square, marked by a Blue Plaque.

^3 none William Cowper’s poem “The Task”, book V “The Winter Evening”References

- Bourne Society, The. (1996) Village Histories 1 - Purley

- Bourne Society, The. (1987) Local History Records Vol. XXVI - The Story of Foxley Woods - John Bishop

- Bourne Society, The. Bulletin 118.

- Cave, Henry W. (1900) Golden Tips Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. Ltd., London.

- Chancellor, E. Beresford (1925) The Pleasure Haunts of London during four centuries. Constable & Co. Ltd., London.

- Clarke, Ethne (1983) The Cup that Cheers. The Reader’s Digest Association Limited, London.

- Forrest, Denys M. (1967) A Hundred Years of Ceylon Tea 1867 - 1967. Chatto & Windus, London.

- Forrest, Denys M. (1973) Tea for the British. Chatto & Windus, London.

- Horniman Public Museum & Public Park Trust (1993) Mr. Horniman and the Tea Trade. Horniman Trust, London.

- Huxley, Gervas (1956) Talking of Tea. Thames & Hudson, London.

- James, Diana (1996) The Story of Mazawattee Tea. The Pentland Press Ltd, Durham.

- Lancaster, Osbert (-) The Story of Tea. The Tea Centre, London.

- Living History Publications (1986) Retracing Canals to Croydon and Camberwell (Living History Publications Guide No 7). Living History Publications in association with Environment. Bromley.

- Macfarlane, Alan & Iris (2003) Green Gold: the Empire of Tea. Ebury Press, London.

- Maggs, Ken & Paul De’Athe (1984) South Norwood and the Croydon Canal. North Downs Press, Westerham. New edition available as a download from www.cleis.org.uk

- Mazawattee Tea Co. Ltd (c. 1934) The History of Tea. The Mazawattee Tea Co. Ltd., London.

- Moore, Alderman H. Keatley & W.C. Berwick Sayers (1920) Croydon and the Great War. Corporation of Croydon.

- Pitkin London Guides (1977) All Hallows by the Tower. Pitkin Pictorials, Andover.

- Ramsden, A.R. (1945) Assam Planter. John Gifford Ltd., London.

- Resker, Rev. Robert R. (1916) The History & Development of Purley. Cassell & Co. Ltd, London

- Scott, J.M. (1964) The Tea Story. Heinemann, London.

- Twining, Stephen H. (1956) The House of Twining 1706-1956. R. Twining & Co. Ltd, London.

- Wainwright, David (No date but c. 1970) Brooke Bond: a Hundred Years. Newman Neame Ltd.

- Ward's Directories of Croydon and the area.

- Williams, Ken (1990) The Story of Ty-Phoo. Quiller Press, London.

- Winterman, Mrs M.A. (1988) Croydon’s Parks: An illustrated history. London Borough of Croydon.

- Wroth, Warwick & Arthur Edgar (1896) The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century. Macmillan & Co. Ltd, London.

- The Daily Mirror(April 10, 2010). "History fans find food older than 70 years in homes of late family". The Daily Mirror.

Categories:- Tea brands

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.