- James Madison

-

For other people named James Madison, see James Madison (disambiguation).

James Madison

4th President of the United States In office

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817Vice President George Clinton

Elbridge GerryPreceded by Thomas Jefferson Succeeded by James Monroe 5th United States Secretary of State In office

May 2, 1801 – March 3, 1809President Thomas Jefferson Preceded by John Marshall Succeeded by Robert Smith Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Virginia's 15th districtIn office

March 4, 1793 – March 3, 1797Preceded by Constituency established Succeeded by John Dawson Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Virginia's 5th districtIn office

March 4, 1789 – March 3, 1793Preceded by Constituency established Succeeded by George Hancock Delegate to the

Congress of the Confederation

from VirginiaIn office

March 1, 1781 – November 1, 1783Preceded by Position established Succeeded by Thomas Jefferson Personal details Born March 16, 1751

Port Conway, Virginia ColonyDied June 28, 1836 (aged 85)

Montpelier, Virginia, U.S.Political party Democratic-Republican Party Spouse(s) Dolley Todd Children John (Stepson) Alma mater Princeton University Profession Planter Signature

James Madison, Jr. (March 16, 1751 (O.S. March 5) – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States (1809–1817) and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United States Bill of Rights.[1] He inherited tobacco land and owned slaves although he spent his entire adult life as a career politician.

His collaboration with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay produced the Federalist Papers (1788), which became the most influential explanation and defense of the Constitution after its publication. Madison's most distinctive belief as a political theorist was the principle of divided power. Madison believed that "parchment barriers" were not sufficient to protect the rights of citizens. Power must be divided, both between federal and state governments (federalism), and within the federal government (checks and balances) to protect individual rights from the tyranny of the majority.

In 1789, Madison became a leader in the new House of Representatives, drafting many basic laws. In one of his most famous roles, he drafted the first ten amendments to the Constitution and thus is known as the "Father of the Bill of Rights".[2] Madison worked closely with the President George Washington to organize the new federal government. Breaking with Hamilton and what became the Federalist party in 1791, Madison and Thomas Jefferson organized what they called the Republican Party (later called by historians the Democratic-Republican Party)[3] in opposition to key policies of the Federalists, especially the national bank and the Jay Treaty. He co-authored, along with Thomas Jefferson, the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions in 1798 to protest the Alien and Sedition Acts.

As Jefferson’s Secretary of State (1801–1809), Madison supervised the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation’s size. As president (1809-17), after the failure of diplomatic protests and an embargo, he led the nation into the War of 1812. The war was in response to British encroachments on American honor and rights as well as to facilitate American settlement in the Midwest which was blocked by Indian allies of the British. The war was an administrative nightmare without a strong army or financial system, leading Madison afterwards to support a stronger national government and a strong military, as well as a national bank of the sort he had long opposed.

Early life

James Madison, Jr. was born at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia on March 16, 1751, (March 5, 1751, Old Style, Julian calendar). He grew up as the oldest of twelve children.[4] His father, James Madison, Sr. (1723–1801), was a tobacco planter who grew up on an estate in Orange County, Virginia, which he inherited upon reaching maturity. He later acquired more property and, with 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), became the largest landowner and a leading citizen of Orange County. His mother, Nelly Conway Madison (1731–1829), was born at Port Conway, Virginia, the daughter of a prominent planter and tobacco merchant. Madison's parents were married on September 15, 1749.[4] In addition to James Jr., Nelly and James Sr. had seven more boys and four girls. Three brothers of James Jr. died as infants, including one stillborn, and in the summer of 1775, the lives of his sister, Elizabeth (age 7), and his brother, Reuben (age 3), were cut short by a dysentery epidemic that swept through Orange County.[4][5]

Education

Montpelier, Madison's tobacco plantation in Virginia

Montpelier, Madison's tobacco plantation in Virginia

From ages 11 to 16, a young "Jemmy" Madison studied under Donald Robertson, an instructor at the Innes plantation in King and Queen County, Virginia. Robertson was a Scottish teacher who flourished in the southern states. From Robertson, Madison learned mathematics, geography, and modern and ancient languages. He became especially proficient in Latin. Madison said that he owed his bent for learning "largely to that man (Robertson)."

At age 16, he began a two-year course of study under the Reverend Thomas Martin, who tutored Madison at Montpelier in preparation for college. Unlike most college-bound Virginians of his day, Madison did not choose the College of William and Mary because the lowland climate of Williamsburg might have strained his delicate health. Instead, in 1769, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University.

Through diligence and long hours of study that may have damaged his health,[6] Madison graduated in 1771. His studies there included Latin, Greek, science, geography, mathematics, rhetoric, and philosophy. Great emphasis also was placed on speech and debate. After graduation, Madison remained at Princeton to study Hebrew and political philosophy under university president John Witherspoon before returning to Montpelier in the spring of 1772. Afterwards, he knew Hebrew quite well. Madison studied law, but out of his interest in public policy, not with the intent of practicing law as a profession.[7]

Marriage and family

James Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, a widow, on September 15, 1794, at Harewood, in what is now Jefferson County, West Virginia.[4] Madison adopted Todd's one surviving son, John Payne Todd after the marriage. Dolley Payne was born May 20, 1768, at the New Garden Quaker settlement in North Carolina, where her parents, John Payne and Mary Coles Payne, lived briefly. Dolley's sister, Lucy Payne, had married George Steptoe Washington, a nephew of President Washington.

As a member of Congress, Madison had doubtless met the widow Todd at social functions in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital. In May 1794, he took formal notice of her by asking their mutual friend Aaron Burr to arrange a meeting. The encounter apparently went smoothly for a brisk courtship followed, and by August, she had accepted his proposal of marriage. For marrying Madison, a non-Quaker, she was expelled from the Society of Friends.

Early political career

As a young man, Madison witnessed the persecution of Baptist preachers arrested for preaching without a license from the established Anglican Church. He worked with the preacher Elijah Craig on constitutional guarantees for religious liberty in Virginia.[8] Working on such cases helped form his ideas about religious freedom. Madison served in the Virginia state legislature (1776–79) and became known as a protégé of Thomas Jefferson. He attained prominence in Virginia politics, helping to draft the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. It disestablished the Church of England and disclaimed any power of state compulsion in religious matters. He excluded Patrick Henry's plan to compel citizens to pay for a congregation of their own choice.

Madison's cousin, the Right Reverend James Madison (1749–1812), became president of the College of William & Mary in 1777. Working closely with Madison and Jefferson, Bishop Madison helped lead the College through the changes involving separation from both Great Britain and the Church of England. He also led college and state actions that resulted in the formation of the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia after the Revolution.

James Madison persuaded Virginia to give up its claims to northwestern territories—consisting of most of modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota—to the Continental Congress, which created the Northwest Territory in 1783. These land claims overlapped partially with other claims by Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and possibly others. All of these states ceded their westernmost lands, with the understanding that new states could be formed from the land, as they were. As a delegate to the Continental Congress (1780–83), Madison was considered a legislative workhorse and a master of parliamentary coalition building.[9] He was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for a second time from 1784 to 1786.

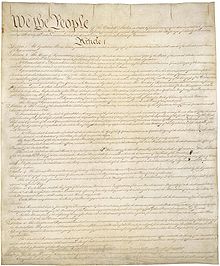

Father of the Constitution

The Constitution is significant not only as a founding charter of the United States, and as a bulwark of freedom, but also in that the underlying assumptions are different from what preceded it. In the case of the Magna Carta the barons went to the king and demanded that he grant them rights. In the Constitution, the assumption is that the people already have those rights. Madison and the other Founders referred to them as natural rights, in that they are inherent and universal to all men and not granted or conceded by the state or any other power.[10][11]

"We the People" would found the government and specify exactly what powers it would have, not the other way around. This was upside down from what had been the norm in world history.[12]

Prior to the Constitution, the thirteen states were bound together by the Articles of Confederation, which was essentially a military alliance between them used to fight the Revolutionary War. This arrangement did not work particularly well, and after the war was over, it was even less successful. Congress had no power to tax, and as a result was not paying the debts left over from the Revolution. Madison and other leaders, such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, were very concerned about this. They feared a break-up of the union and national bankruptcy.[13]

As Madison wrote, "a crisis had arrived which was to decide whether the American experiment was to be a blessing to the world, or to blast for ever the hopes which the republican cause had inspired." Largely at Madison's instigation, a national convention was called in 1787. Madison was the only delegate to arrive with a comprehensive plan, which became known as the Virginia Plan, as to how to solve the problems of the Articles. The Virginia Plan immediately became the focus of all debate, and is the basis of the U.S. Constitution today.[14][15]

The key element of the Constitution is the division of power. Having just fought an eight-and-a-half-year Revolutionary War to get rid of too much concentrated power in hands of a king, the Framers had no interest in recreating that, even with an elected government, which is why they divided power between the federal government and the state governments. Furthermore, they separated power within the federal government, forming three branches.

The powers of Congress, also called federal powers, are enumerated in Article I, Section 8. All other powers belong to the states or individual citizens. This arrangement is reiterated in the Bill of Rights (the 10th Amendment).

As Madison wrote, "The federal and state governments are in fact but different agents and trustees for the people, instituted with different powers, and designated for different purposes."[16] Madison expressed the overall challenge the Framers faced in this way, "In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself."[17]

Madison was the best-prepared delegate to come to the Constitutional Convention. In preparation for creating the Virginia Plan, he pored over crates of books that Jefferson sent him from France on every form of government ever tried. Historian Douglas Adair called Madison's work "probably the most fruitful piece of scholarly research ever carried out by an American."[18]

Madison was a leader in initiating the Constitutional Convention; during the course of the Convention he spoke over two hundred times, and his fellow delegates rated him highly. For example, William Pierce wrote that "...every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. In the management of every great question he evidently took the lead in the Convention... he always comes forward as the best informed Man of any point in debate." Historian Clinton Rossiter regarded Madison's performance as "a combination of learning, experience, purpose, and imagination that not even Adams or Jefferson could have equaled."[19]

Federalist Papers

Main article: Federalist PapersThe Constitution as it came out of the convention in Philadelphia was just a proposal. It would have no effect until ratified by “We the People.” It would not be ratified by state legislatures but by special conventions called in each state to decide that sole question of ratification.[20]

Madison was a leader in the ratification effort. He, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay wrote the Federalist Papers, a series of 85 newspaper articles published throughout the 13 states to explain how the proposed Constitution would work. They were also published in book form and became a virtual debater’s handbook for the supporters of the Constitution in the ratifying conventions.[21]

Historian Clinton Rossiter called the Federalist Papers “the most important work in political science that ever has been written, or is likely ever to be written, in the United States.”[22]

The ratification effort was not easy. Having just gotten rid to too much concentrated, centralized power, the states were leery of creating a powerful central government. Patrick Henry, who opposed the Constitution, feared that it would trample on the independence of the states and the rights of citizens. In the Virginia ratifying convention, Madison, who was a terrible public speaker, had to go up against Henry, who was the finest orator in the country.[23]

Virginia was one of the largest and most populous states. If Virginia didn’t ratify the Constitution, it would not succeed. Even though Henry was by far the more powerful and dramatic speaker, Madison won the debate with facts. Madison pointed out that it was a limited government that would be created, and that the powers delegated ‘to the federal government are few and defined.”[24]

Madison was given the honor of being called the “Father of the Constitution” by his peers in his own lifetime. However, he was modest, and he protested the title as being "a credit to which I have no claim... The Constitution was not, like the fabled Goddess of Wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands".[25]

He wrote Hamilton at the New York ratifying convention, stating his opinion that "ratification was in toto and 'for ever'". The Virginia convention had considered conditional ratification worse than a rejection.[26]

Author of Bill of Rights

Initially Madison "adamantly maintained ... that a specific bill of rights remained unnecessary because the Constitution itself was a bill of rights."[27] Madison had three main objections to a specific bill of rights:

- It was unnecessary, since it purported to protect against powers that the federal government had not been granted;

- It was dangerous, since enumeration of some rights might be taken to imply the absence of other rights; and

- At the state level, bills of rights had proven to be useless paper barriers against government powers.[2]

However, the anti-Federalists demanded a bill of rights in exchange for their support for ratification. Madison initially opposed the idea for the reasons stated above, but won the day for the Constitution by promising to add a bill of rights, and he came to be the author of it.

A vengeful Patrick Henry used his power to keep the Virginia legislature from appointing Madison as one of the state’s senators. Henry even gerrymandered Madison’s home district, filling it with anti-federalists, in an attempt to prevent Madison from becoming a Congressman. Madison managed to win anyway, and became an important leader in Congress.[28]

People submitted more than 200 amendment proposals from across the new nation. Some urged Madison to forget about creating a bill of rights now that the country was up and running, but he kept his promise. He synthesized the proposals into a list of 12 proposed amendments and even “hounded his colleagues relentlessly” to accept the proposed amendments.[29]

Madison felt strongly that federal powers were limited by enumerating (making a list of) them (Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution). Anything not on the list was not a federal power. So then, by creating a bill of rights, the same would apply. Anything not on the list would be excluded.[30]

However, he also felt, as other Founders did, that Americans have countless natural rights – too many to put on a list. For example, the right to travel freely throughout the country, the right to have children, the right to sign a contract, the right to own land, etc. (none of which are listed in the Bill of Rights). How then to respond to the public clamor for a bill of rights? There would not be enough paper to list them all.[31]

Madison solved this dilemma with the 9th Amendment, which says that just because the Bill of Rights didn’t list them all does not mean that other rights of the people don’t exist.

By 1791, the last ten of Madison’s proposed amendments were ratified and became the Bill of Rights. Contrary to his wishes, the Bill of Rights was not integrated into the main body of the Constitution, and it did not apply to the states until the passages of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments restricted the powers of the states. The Second Amendment originally proposed by Madison (but not then ratified) was later ratified in 1992 as the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. The remaining proposal was intended to accommodate future increase in the members of the House of Representatives.

Opposition to Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was a loose constructionist who said the Constitution was designed to enable a government to operate, using implied powers. Madison and Jefferson were strict constructionists who wanted the text of the document to be construed to give the federal government less power.[32]

To Madison, the Constitution was written as a social compact in which “We the People” granted specific, limited powers to the federal government, as enumerated (i.e., listed) in Article I, Section 8. All other powers are reserved to the states or the people themselves.

Hamiltonians argued that the “general welfare” clause in the preamble was a general grant of power to the federal government to benefit the general welfare of the country. The Madisonians countered that it would be an absurdity to have bothered to write up a specific list of federal powers if the preamble was to be considered a general grant power. Also, the preamble’s words were taken from the Articles of Confederation, and no one had ever interpreted that to have been a general grant of power.[33]

The Hamiltonians focused on the “necessary and proper” clause. For example, since Article I, Section 8 grants the federal government the power to tax, and a national bank would make it easier to collect taxes, then by the “necessary and proper” clause, a national bank was constitutional. The Madisonians said no--“necessary and proper,” was not “convenient and proper.” It may be more convenient to collect taxes with a national bank, but it is not necessary.[34]

Both sides were inconsistent in the debates. Hamilton was consistently in favor of enlarging federal powers, and was more than willing to interpret the Constitution loosely to achieve this end.[35]

Madison, had actually argued for additional federal powers in the Constitutional Convention, but was willing to live with the Constitution as adopted and ratified. He considered the Constitution to be a social compact between the people and their government, and that fidelity to that agreement was critical to preventing abuse by officeholders.

Ron Chernow finds Hamilton more consistent than Madison; Gary Rosen finds the opposite.[36]

Some historians feel that the chief characteristic of Madison's time in Congress was his work to limit the power of the federal government. Wood (2006a) argued that Madison never wanted a national government that took an active role. He was horrified to discover that Hamilton and Washington were creating "a real modern European type of government with a bureaucracy, a standing army, and a powerful independent executive".[37] Chernow argues that "for Madison, Hamilton was becoming the official voice of wealthy aristocrats who were grabbing the reins of federal power. Madison felt betrayed by Hamilton but it was Madison who had deviated from their former reading of the Constitution."[38] Specifically, while Madison wrote in the Federalist number 44 that "No axiom is more clearly established in law or in reason than wherever the end is required, the means are authorized; wherever a general power to do a thing is given, every particular power for doing it is included", he opposed Hamilton's attempts to use article 1, section 8 of the Constitution in this way.[39]

Debates on foreign policy

When Britain and France went to war in 1793 the U.S. was caught in the middle. The 1778 treaty of alliance with France was still in effect, yet most of the new country's trade was with Britain. War with Britain seemed imminent in 1794, as the British seized hundreds of American ships that were trading with French colonies. Madison believed that Britain was weak and America was strong, and that a trade war with Britain, although risking a real war by the British government, probably would succeed, and would allow Americans to assert their independence fully. Great Britain, he charged, "has bound us in commercial manacles, and very nearly defeated the object of our independence." As Varg explains, Madison discounted the much more powerful British army and navy for "her interests can be wounded almost mortally, while ours are invulnerable." The British West Indies, Madison maintained, could not live without American foodstuffs, but Americans could easily do without British manufactures. This faith led him to the conclusion "that it is in our power, in a very short time, to supply all the tonnage necessary for our own commerce".[40] However, George Washington avoided a trade war and instead secured friendly trade relations with Britain through the Jay Treaty of 1794. Madison threw his energies into fighting the Treaty—his mobilization of grass roots support helped form the First Party System. He failed in both Senate and House, and the Jay Treaty led to ten years of prosperous trade with Britain (and anger on the part of France leading to the Quasi-War) All across the land voters divided for and against the Treaty and other key issues, and thus became either Federalists or Jeffersonian Republicans.

First Party System

Supporters for ratification of the Constitution had become known as the Federalist Party. Those opposing the proposed Constitution were labeled Anti-Federalists, but neither group was a political party in the modern sense. Following ratification of the Constitution and formation of the first government in 1789, the Federalists became the proponents of a strong central government, while former Anti-Federalists argued for a very limited federal role. Madison and Thomas Jefferson were the leaders of this group, which began to be known as the Democratic-Republican Party. As first Secretary of the Treasury, the Federalist Hamilton created many new federal institutions, including the Bank of the United States. Madison led the unsuccessful attempt in Congress to block Hamilton's proposal, arguing that the new Constitution did not explicitly allow the federal government to form a bank. As early as May 26, 1792, Hamilton complained, "Mr. Madison cooperating with Mr. Jefferson is at the head of a faction decidedly hostile to me and my administration."[41] On May 5, 1792, Madison told Washington, "with respect to the spirit of party that was taking place ...I was sensible of its existence".[42]

Adams years

In 1798 under President John Adams the U.S. and France unofficially went to war—the Quasi War, that involved naval warships and commercial vessels battling in the Caribbean. The Federalists created a standing army and passed laws against French refugees engaged in American politics and against Republican editors. Congressman Madison and Vice President Jefferson were outraged. Madison secretly drafted a resolution for Virginia declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts to be unconstitutional and noted that "states, in contesting obnoxious laws, should 'interpose for arresting the progress of the evil.'"[43] This, according to Chernow, "was a breathtaking evolution for a man who had pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws."[44]

Some historians argue that Madison changed radically from a nationally oriented ally of Hamilton in 1787–88 to a states'-rights-oriented opponent of a strong national government by 1795 and then back to his original view while president. Madison started the first transition by opposing Hamilton.[45][46] Madison opposed legislation that to his mind was clearly unconstitutional, such as Hamilton's proposed National Bank. He also opposed the federal assumption of state debts and the Jay Treaty, which many (including Washington) considered to be poorly negotiated.[45] Madison succeeded in blocking a proposal for high tariffs.

Most historians say that Madison abandoned strict constructionism in 1815, saying that it was not the text of the Constitution that mattered but the expressed will of the people. Despite attacks by "Quids" or "Old Republicans" such as John Randolph of Roanoke who still held to strict constructionism, Madison now favored a national bank, a standing professional army and a federal program of internal improvements as advocated by Henry Clay.[47]

Chernow feels that Madison's politics remained closely aligned with Jefferson's until the experience of a weak national government during the War of 1812 caused Madison to appreciate the need for a strong central government to aid national defense. He then began to support a national bank, a stronger navy, and a standing army. However, other historians, such as Gary Rosen, Lance Banning and Gordon S. Wood, see Madison's views as being remarkably consistent over a political career spanning half a century.[48][49][50]

United States Secretary of State 1801–1809

Further information: Louisiana Purchase and Embargo Act of 1807The main challenge which faced the Jefferson Administration was navigating between the two great empires of Britain and France, which were almost constantly at war. The first great triumph was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, made possible when Napoleon realized he could not defend that vast territory, and it was to France's advantage that Britain not seize it.

Some historians, such as Ron Chernow, are quick to accuse Madison and President Jefferson of ignoring their "strict construction" view of the Constitution to take advantage of the opportunity. Jefferson would have preferred to have a constitutional amendment authorizing the purchase (in line with his strict-constructionist philosophy). However, Madison pointed out that it wasn't necessary, even under a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Countries acquire territory in one of two ways: by conquest or by treaty. The Louisiana Purchase is a treaty (in other words, a contract between nations). Presidents are specifically authorized by the Constitution to negotiate treaties (Article II, Section 2), which is what Jefferson did. Recognizing the Louisiana Purchase as the land bargain of the century, the Senate quickly ratified the treaty. The House, with equal alacrity, passed enabling legislation. Each branch of government performed its role as specified in the Constitution.[51][52]

In the wars raging in Europe Madison tried to maintain neutrality between Britain and France, but at the same time insisted on the legal rights of the U.S. as a neutral under international law. Neither London nor Paris showed much respect, however. Madison and Jefferson decided on an embargo to punish Britain and France, forbidding Americans to trade with any foreign nation. The embargo failed as foreign policy, and instead caused massive hardships up and down the seaboard, which depended on foreign trade. The Federalist made a comeback in the Northeast by attacking the Embargo, which was allowed to expire just as Jefferson was leaving office.[53]

At the start of his term as Secretary of State he was a party to the Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison, in which the doctrine of judicial review was asserted by the high Court, much to the annoyance of the Jeffersonians who did not want an independent, powerful judiciary.

The party's Congressional Caucus chose presidential candidates, and Madison was selected in the election of 1808, easily defeating Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

Presidency 1809–1817

James Madison engraving by David Edwin from between 1809 and 1817

James Madison engraving by David Edwin from between 1809 and 1817

Bank of the United States

The twenty-year charter of the first Bank of the United States was scheduled to expire in 1811, the second year of Madison's administration. Madison failed in blocking the Bank in 1791, and waited for its charter to expire. Secretary of the Treasury Gallatin said the bank was a necessity; when he had to finance the War of 1812 he discovered how difficult it was to finance the war without the Bank. Congress passed a bill chartering a second national bank in 1814, which Madison vetoed, because of the particulars of the legislation, rather than constitutional grounds.[54]

The next year, in his annual address, Madison stated that a national bank might “deserve consideration.” Congress passed such legislation, which Madison signed. His strict-constructionist views were still firmly intact, but he acquiesced on the bank issue because it had “undergone ample discussions in its passage through the several branches of the Government. It had been carried into execution throughout a period of twenty years with annual legislative recognition…and with the entire acquiescence of all the local authorities, as well as of the nation at large; to all of which may be added, a decreasing prospect of any change in the public opinion adverse to the constitutionality of such an institution.”[55][56]

Madison’s primary concern was that the Constitution would achieve the veneration he felt it deserved, and that the original understanding of its meaning by the ratifying conventions would be preserved. The Hamiltonians’ loose interpretation of the Constitution’s “general welfare clause” and “necessary and proper clause” had been the biggest threat to this.[57]

However, time had passed, the Democratic-Republicans had occupied the White House for four terms (Jefferson for two, and Madison for two), and Alexander Hamilton was dead. Hamilton’s political party, the Federalist Party, was on its way out of existence. Madison felt he could safely sign the bank bill (creating the Second Bank of the United States) without causing a fundamental change in constitutional meaning.[58][59]

War of 1812

Main article: War of 1812British insults continued. Britain used their navy to prevent American ships from trading with France (with which Britain was at war). The United States, which was a neutral nation, considered this act to be against international law. Britain also armed Indian tribes in the Northwest Territory and encouraged them to attack settlers, even though Britain had ceded this territory to the United States by treaties in 1783 and 1794. Most insulting though was the impressment of seamen as the Royal Navy boarded American ships on the high seas. The United States looked upon this as no less an affront to American sovereignty than if the British had invaded American soil.[60][61]

American diplomatic protests to Britain were ignored, and the embargo backfired, hurting the Americans more than the British. The insult to national honor was intolerable and Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to the new nation.[62] An angry public elected a “war hawk” Congress, led by such luminaries as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war, which passed along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition from the Federalists and the Northeast.[61][63]

A panel of scholars in 2006 ranked Madison’s failure to avoid war as the sixth worst presidential mistake ever made.[64][65]

Hurriedly Madison called on Congress to put the country “into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis,” specifically recommending enlarging the army, preparing the militia, finishing the military academy, stockpiling munitions, and expanding the navy. Congress voted to enlarge the army with five-year enlistments, which could not be obtained and refused to enlarge the navy.[66] Madison had not made any serious war plans or built up the army. The senior command at the War Department and in the field proved incompetent or cowardly—the general at Detroit surrendered to a smaller British force without firing a shot. Gallatin at the Treasury discovered the war was almost impossible to fund since the national bank had been closed and major financiers in the Northeast refused to help. Madison believed the U.S. could easily seize Canada and thus cut off food supplies to the West Indies, making for a good bargaining chip at the peace talks. But the invasion efforts all failed. Madison had assumed the militia would rally to the flag and invade Canada, but the governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate and their militias either sat out the war or refused to leave the state.[67]

Britain did not want war as it was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War (in Spain), and the Royal Navy was compelled to blockade most of the coast of Europe.Britain had only 6000 regulars in Canada, supplemented by local Canadian militia.[68]

The war began badly for the Americans, as the British repulsed invasions of Canada and blockaded the coast (while trading extensively with disloyal elements in the Northeast). Economic hardship was severe, but entrepreneurs built factories that soon became the basis of the industrial revolution in America. The British raided Washington in 1814, as Madison headed a dispirited militia. Dolley Madison rescued White House valuables and documents in the nick of time, as the British burned the White House, the Capitol and other public buildings.[69][70]

The British armed American Indians in the West, most notably followers of Tecumseh. However the British lost control of Lake Erie at the naval Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, and were forced to retreat. General William Henry Harrison caught up with them at the Battle of the Thames, destroyed the British and Indian armies, killed Tecumseh, and permanently destroyed Indian power in the Great Lakes region. Meanwhile General Andrew Jackson destroyed the Indian power in the Southeast. The Indians were the big losers in the war.

Madison faced formidable obstacles — a divided cabinet, a factious party, a recalcitrant Congress, obstructionist governors, and incompetent generals, together with militia who refused to fight outside their states. Most serious was lack of unified popular support. There were serious threats of disunion from New England, which engaged in massive smuggling to Canada and refused to provide financial support or soldiers.[71] However, by 1813, the main Indian threats in the South and West had been destroyed by Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison, respectively.

Despite being a young nation without much of a military, going up against one of the superpowers of the day, the United States did better than might be expected. There were impressive naval successes by American frigates and other vessels, such as the USS Constitution, USS United States, USS Chesapeake, USS Hornet, USS Wasp, and USS Essex. In a famous three-hour battle with the HMS Java, the USS Constitution earned her nickname, “Old Ironsides.”[72]

The U.S. fleet on Lake Erie went up against a superior British force there and destroyed or captured the entire British Fleet on the lake. Commander Oliver Hazard Perry reported his victory with the simple statement, “We have met the enemy, and they are ours.”[73]

America had built up one of the largest merchant fleets in the world in the decade before the war. Many of these ships were authorized to become privateers in the war. They armed themselves and captured 1,800 British ships.[74]

The courageous, successful defense of Ft. McHenry, which guarded the seaway to Baltimore, against one of the most intense naval bombardments in history (over 24 hours), led Francis Scott Key to write the poem which became the U.S. national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.”[75]

In New Orleans, Gen. Andrew Jackson put together a force of everyone he could find, including regular Army troops, militia, frontiersmen, Creoles, and even Jean Lafitte’s pirates. In the battle there, which took place two weeks after the peace treaty was signed (due to communication being slow), the Americans destroyed an entire British army.[76]

The Treaty of Ghent ended the war in 1815, with no territorial gains on either side, but the Americans felt that their national honor had been restored in what has been called “the Second War of American Independence.”[77]

Postwar

With peace finally established, the U.S. was swept by a sense that it had secured solid independence from Britain. The Federalist Party collapsed and eventually disappeared from politics, as an Era of Good Feelings emerged with a much lower level of political fear and vituperation, although political contention certainly continued.

Although Madison had accepted the necessity of a Hamiltonian national bank, an effective taxation system based on tariffs, a standing professional army and a strong navy, he drew the line at internal improvements as advocated by his Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin. In his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed on states' rights grounds the Bonus Bill of 1817 that would have financed "internal improvements," including roads, bridges, and canals:[78]

Having considered the bill ... I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling this bill with the Constitution of the United States.... The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified ... in the ... Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers.Madison rejected the view of Congress that the General Welfare provision of the Taxing and Spending Clause justified the bill, stating:

Such a view of the Constitution would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them, the terms "common defense and general welfare" embracing every object and act within the purview of a legislative trust.Madison urged a variety of measures that he felt were "best executed under the national authority," including federal support for roads and canals that would "bind more closely together the various parts of our extended confederacy."[79]

International

The Second Barbary War brought to a conclusive end the American practice of paying tribute to the pirate states in the Mediterranean and marked the beginning of the end of the age of piracy in that region.

Administration and cabinet

The Madison Cabinet Office Name Term President James Madison 1809–1817 Vice President George Clinton 1809–1812 Elbridge Gerry 1813–1814 Secretary of State Robert Smith 1809–1811 James Monroe 1811–1817 Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin 1809–1814 George W. Campbell 1814 Alexander J. Dallas 1814–1816 William H. Crawford 1816–1817 Secretary of War William Eustis 1809–1813 John Armstrong, Jr. 1813–1814 James Monroe 1814–1815 William H. Crawford 1815–1816 Attorney General Caesar A. Rodney 1809–1811 William Pinkney 1811–1814 Richard Rush 1814–1817 Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton 1809–1813 William Jones 1813–1814 Benjamin W. Crowninshield 1814–1817 - Madison is the only president to have had two vice-presidents die while in office.

Judicial appointments

Main article: James Madison judicial appointmentsSupreme Court

Madison appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Gabriel Duvall – 1811

- Joseph Story – 1812

Other courts

Madison appointed eleven other federal judges, two to the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, and nine to the various United States district courts. One of those judges was appointed twice, to different seats on the same court.

States admitted to the Union

Later life

Gilbert Stuart Portrait of James Madison c. 1821

Gilbert Stuart Portrait of James Madison c. 1821

When Madison left office in 1817, he retired to Montpelier, his tobacco plantation in Virginia; not far from Jefferson's Monticello. Madison was then 65 years old. Dolley, who thought they would finally have a chance to travel to Paris, was 49. As with both Washington and Jefferson, Madison left the presidency a poorer man than when he entered, due to the steady financial collapse of his plantation. Some historians speculate that his mounting debt was one of the chief reasons why he refused to allow his notes on the Constitutional Convention, or its official records which he possessed, to be published in his lifetime. "He knew the value of his notes, and wanted them to bring money to his estate for Dolley's use as his plantation failed—he was hoping for one hundred thousand dollars from the sale of his papers, of which the notes were the gem."[80] Madison's financial troubles and deteriorating mental and physical health would continue to consume him.

In his later years, Madison also became extremely concerned about his legacy. He took to modifying letters and other documents in his possessions: changing days and dates, adding and deleting words and sentences, and shifting characters. By the time he had reached his late seventies, this "straightening out" had become almost an obsession. This can be seen by his editing of a letter he had written to Jefferson criticizing Lafayette: Madison not only inked out original passages, but went so far as to imitate Jefferson's handwriting as well.[81] In Madison's mind, this may have represented an effort to make himself clear, to justify his actions both to history and to himself.

During the final six years of his life, amid a sea of personal [financial] troubles that were threatening to engulf him...At times mental agitation issued in physical collapse. For the better part of a year in 1831 and 1832 he was bedridden, if not silenced...Literally sick with anxiety, he began to despair of his ability to make himself understood by his fellow citizens.[82]In 1826, after the death of Jefferson, Madison followed Jefferson as the second Rector ("President") of the University of Virginia. It would be his last occupation. He retained the position as college chancellor for ten years, until his death in 1836.

In 1829, at the age of 78, Madison was chosen as a representative to the constitutional convention in Richmond for the revising of the Virginia state constitution; this was to be Madison's last appearance as a legislator and constitutional drafter. The issue of greatest importance at this convention was apportionment. The western districts of Virginia complained that they were underrepresented because the state constitution apportioned voting districts by county, not population. Westerners' growing numbers thus did not yield growing representation. Western reformers also wanted to extend suffrage to all white men, in place of the historic property requirement. Madison tried to effect a compromise, but to no avail. Eventually, suffrage rights were extended to renters as well as landowners, but the eastern planters refused to adopt population apportionment. Madison was disappointed at the failure of Virginians to resolve the issue more equitably. "The Convention of 1829, we might say, pushed Madison steadily to the brink of self-delusion, if not despair. The dilemma of slavery undid him."[83][84]

Although his health had now almost failed, he managed to produce several memoranda on political subjects, including an essay against the appointment of chaplains for Congress and the armed forces, because this produced religious exclusion, but not political harmony.[85]

Madison lived on until 1836, increasingly ignored by the new leaders of the American polity. He died at Montpelier on June 28, the last of the Founding Fathers to die.[86] He was buried in the Madison Family Cemetery at Montpelier.[5]

Legacy

As historian Garry Wills wrote:

Madison's claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues.... As a framer and defender of the Constitution he had no peer.... The finest part of Madison's performance as president was his concern for the preserving of the Constitution.... No man could do everything for the country – not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough.[87]George F. Will once wrote that if we truly believed that the pen is mightier than the sword, our nation’s capital would have been called “Madison, D.C.”, instead of Washington, D.C.[88][89]

- Montpelier, his family's estate and his home in Orange, Virginia, is a National Historic Landmark

- Many counties, several towns, cities, educational institutions, a mountain range and a river are named after Madison.

- Madison County - lists counties named for him

- Cities: e.g. Madison, Wisconsin

- The James Madison College of public policy at Michigan State University; James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia - its athletic teams are called the James Madison Dukes; the James Madison Institute was named in honor of his contributions to the Constitution.

- The Madison Range was named in honor of the future President then U.S. Secretary of State by Meriwether Lewis as the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through Montana in 1805. The Madison River in southwestern Montana, named in 1805 by Lewis & Clark.[90]

- Mount Madison in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in New Hampshire is named after Madison.

- Two U.S. Navy ships have been named USS James Madison and three USS Madison.

- Madison's portrait was on the U.S. $5000 bill.[91]

Madison Cottage in New York City was named in his honor shortly after his death. It later became Madison Square, with its numerous landmarks.[92]

James Madison was honored on a Postage Issue of 1894"Madison Cottage" on the site of the Fifth Avenue Hotel at Madison Square, New York City, 1852Auction of books of James Madison's library, Orange County, Virginia, 1854Presidential Dollar of James MadisonSee also

- Report of 1800, produced by Madison to support the Virginia Resolutions

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

- U.S. Constitution, floor leader in Convention, ratification debates

Notes

- ^ Ralph Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, (1971) pp.229, 289-92,

- ^ a b Wood, 2006b.

- ^ James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, March 2, 1794.) "I see by a paper of last evening that even in New York a meeting of the people has taken place, at the instance of the Republican Party, and that a committee is appointed for the like purpose."

*Thomas Jefferson to President Washington, May 23, 1792 "The republican party, who wish to preserve the government in its present form, are fewer in number. They are fewer even when joined by the two, three, or half dozen anti-federalists,..."

*Thomas Jefferson to John Melish, January 13, 1813. "The party called republican is steadily for the support of the present constitution" - ^ a b c d Chapman, C. Thomas (22 May 2006). "Descendants of Ambrose Madison, the Grandfather of President James Madison, Jr". The National Society of Madison Family Descendants. pp. 1–20. http://www.jamesmadisonfamily.com/docs/AmbroseMadison.pdf. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ a b "The Madison Cemetery". James Madison's Montpelier. 2011. http://www.montpelier.org/explore/gardens/cemeteries_madison.php. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Brennan, Daniel. "Did James Madison suffer a nervous collapse due to the intensity of his studies?" Mudd Manuscript Library Blog, Princeton University Archives and Public Policy Papers Collection, Princeton University.

- ^ Ketcham, Ralph, James Madison: A Biography, p. 56, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, CT, 1971.

- ^ Ralph Louis Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1971; paperback, 1990, p. 57, accessed February 6, 2009

- ^ James Madison Biography, American-Presidents.com, Accessed on July 29, 2009.

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of the Founding, pp. 10-38, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed., The Federalist Papers, pp. 480-481, Penguin Putnam, Inc., New York, NY, 1961.

- ^ Smith, Duane E., We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution, pp. 2-18, Center for Civic Education, Calabasas, CA, 1995.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard B., Are We to be a Nation? pp. 11-12, 81-109, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1987.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen, James Madison: The Founding Father, pp. 14-21, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 1987.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, 1787: The Grand Convention, pp.41-57, MacGibbon & Key Ltd., New York, 1968.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen, James Madison: The Founding Father, pp. 33, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 1987.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen, James Madison: The Founding Father, p. 33, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 1987.

- ^ Wills, Garry, James Madison, pp. 26-27, Henry Holt & Co., New York, NY, 2002.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen, James Madison: The Founding Father, p. 18, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 1987.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard B., Are We to be a Nation? pp. 199, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1987.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed., The Federalist Papers, p. xiii, Penguin Putnam, Inc., New York, NY, 1961.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed., The Federalist Papers, p. ix, Penguin Putnam, Inc., New York, NY, 1961.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen, James Madison: The Founding Father, pp. 36-39, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 1987.

- ^ Samples, John, James Madison and the Future of Limited Government, pp.25-42, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2002.

- ^ Lance Banning, "James Madison: Federalist," note 1, [1].

- ^ Madison to Hamilton Letter, July 20, 1788, American Memory, Library of Congress, accessed February 2, 2008

- ^ Matthews, 1995, p. 130.

- ^ Labunski, Richard, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, pp.148-150, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2006.

- ^ Labunski, Richard, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, pp.195-7, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2006.

- ^ Samples, John, James Madison and the Future of Limited Government, pp.25-31, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2002.

- ^ Labunski, Richard, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, p. 200, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2006.

- ^ Gary Rosen, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, pp. 144-152, University Press of Kansas, 1999.

- ^ Leonard R. Sorenson, Madison on the ‘General Welfare’ of America (1995) pp. 2-3, 16, 27-28, 51-61, 84-85, 150-170,

- ^ Sorenson, Madison on the ‘General Welfare’ of America, pp. 31-38, 49-65,

- ^ Gary Rosen, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, (1999) pp. 126-155,

- ^ Chernow, Ron, Alexander Hamilton, (2004) pp. 573-4, 2004.

- ^ Wood, 2006a, p. 165.

- ^ Chernow. Alexander Hamilton. p. 350.

- ^ Chernow, Alexander Hamilton. p. 350.

- ^ Paul A. Varg, Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers (Michigan State Univ. Press, 1963), p. 74.

- ^ Hamilton, Writings (Library of America, 2001), p. 738.

- ^ Madison Letters 1 (1865), p. 554.

- ^ Chernow, Alexander Hamilton. p. 573.

- ^ Chernow. Alexander Hamiltonp. 573-74.

- ^ a b Ron Chernow. Aleander Hamilton. 2004. Penguin Book. p. 350.

- ^ "definition of Madison, James". Free Online Encyclopedia. http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Madison%2c+James. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ Maurice G. Baxter, Henry Clay and the American System (2004) P. 47

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of the Founding, pp. 2-4, 6-9, 140-75, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Banning, Lance, The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic, pp.7-9, 161, 165, 167, 228-231, 296-298, 326-7, 330-333, 345-6, 359-61, 371, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1995.

- ^ Banning, Lance, Jefferson and Madison: Three Conversations from the Founding, pp. 78-79, Madison House, Madison, WI, 1995.

- ^ Ketcham, Ralph, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 419-421, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, CT, 1971.

- ^ Parker, Dana T., "Was Thomas Jefferson a Hypocrite?" Orange County Register, Local sec., p. 8, 4-13-2011, Santa Ana, CA, (http://www.ocregister.com/opinion/jefferson-296037-slaves-treaty.html).

- ^ Burton Spivak, Jefferson's English Crisis: Commerce, Embargo and the Republican Revolution (1988)

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, p. 171, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, p. 171-3, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Peterson, Merrill D., ed., James Madison: A Biography in his Own Words, Vol. 2, pp.356-9, Newsweek, New York, NY, 1974.

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, p. 127, 128, 141-52, 154-5, 156-61, 165-175, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Rosen, Gary, American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding, p. 170-5, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999.

- ^ Ketcham, Ralph, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 604-605, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, CT, 1971.

- ^ Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 491-504,

- ^ a b Rutland, James Madison: The Founding Father, pp. 217-24

- ^ Norman K. Risjord, "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor." William And Mary Quarterly 1961 18(2): 196-210. in JSTOR

- ^ Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 508-9,

- ^ "U.S. historians pick top 10 presidential errors". Associated Press article in CTV. February 18, 2006. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20060218/presidential_errors_060218/20060218?hub=World. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ "Results of Presidential Mistakes Survey". McConnell Center, University of Louisville. February 18 and 19, 2006. http://php.louisville.edu/news/news.php?news=533. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 509-15

- ^ Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Short History (U. of Illinois Press, 1995)

- ^ Donald Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (U of Illinois Press, 1989) pp. 72-75

- ^ Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography, pp. 576-8,

- ^ ”Dolley Madison,” Monpelier Web site (http://montpelier.org/explore/dolley_madison/index.php), retrieved 6-5-11.

- ^ Stagg, 1983.

- ^ Toll, Ian W., Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy, pp. 360-65, W. W. Norton, New York, NY, 2006.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore, The Naval War of 1812, pp. 147-152, The Modern Library, New York, NY.

- ^ Rowen, Bob, “American Privateers in the War of 1812,” paper presented to the New York Military Affairs Symposium, Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 2001, revised for Web publication, 2006-8 (http://nymas.org/warof1812paper/paperrevised2006.html), retrieved 6-6-11.

- ^ “The Star-Spangled Banner and the War of 1812,” Encyclopedia Smithsonian (http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/starflag.htm), retrieved 3-10-08.

- ^ Reilly, Robin, The British at the Gates: The New Orleans Campaign in the War of 1812, Putnam, New York, 1974.

- ^ ”Second War of American Independence,” America’s Library Web site (http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/madison/aa_madison_war_1.html) retrieved, 6-6-11.

- ^ Text of Madison's Veto of the Bonus Bill, accessed December 20, 2010

- ^ "Madison’s Seventh Annual Message December 5, 1815 - Lance Banning, Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle [1787]", in Lance Banning, ed., '"Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle" (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004).

- ^ Garry Wills, James Madison (2002), p. 163.

- ^ Wills, p. 162.

- ^ Drew R. McCoy, The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy (1989), p.151.

- ^ McCoy, p. 252.

- ^ Kevin R. C. Gutzman, Virginia's American Revolution: From Dominion to Republic, 1776-1840, ch. 6.)

- ^ He was tempted to admit chaplains for the navy, which might well have no other opportunity for worship.The text of the memoranda

- ^ "The Founding Fathers: A Brief Overview". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_founding_fathers_overview.html. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 164.

- ^ ”Happy Birthday James Madison”, State of the Nation Web site (http://brandon7221.blogspot.com/2010/03/happy-birthday-james-madison.html), Retrieved Mar 19, 2011.

- ^ Quinn, Michael, “Preserving a Legacy: Montpelier Will be Showcase for Madison”, Richmond Times Dispatch, Dec. 5, 2004.

- ^ Allan H. Keith, Historical Stories: About Greenville and Bond County, IL. Consulted on August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Five Thousand Green Seal". The United States Treasury Bureau of Engraving and Printing. http://www.moneyfactory.gov/document.cfm/5/42/159. Retrieved September 17, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of New York City (1995) ISBN 0-300-05536-6

Bibliography

Biographies

- Brant, Irving (1952). "James Madison and His Times". American Historical Review 57 (4): 853–870. doi:10.2307/1844238.

- Brant, Irving (1941–1961). James Madison. 6 volumes., the standard scholarly biography

- Brant, Irving (1970). The Fourth President; a Life of James Madison. Single volume condensation of his 6-vol biography

- Brookhiser, Richard. James Madison (Basic Books; 2011) 287 pages

- Ketcham, Ralph (1971). James Madison: A Biography. Macmillan., recent scholarly biography

- Rakove, Jack (2002). James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (2nd ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0321087976.

- Riemer, Neal (1968). James Madison. Washington Square Press.

- Rutland, Robert A. ed. James Madison and the American Nation, 1751–1836: An Encyclopedia (Simon & Schuster, 1994).

- Rutland, Robert A., James Madison: The Founding Father (University of Missouri Press, 1987).

- Wills, Garry (2002). James Madison. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0805069054. Short bio.

Analytic studies

- Adams, Henry. History of the United States during the Administrations of James Madison (5 vol 1890–91; 2 vol Library of America, 1986). ISBN 0-940450-35-6 Table of contents

- Wills, Garry. Henry Adams and the Making of America (Houghton Mifflin, 2005). a close reading of Adams

- Banning, Lance. Jefferson & Madison: Three Conversations from the Founding (Madison House, 1995).

- Banning, Lance. The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic (Cornell Univ. Press, 1995). online ACLS History e-Book.

- Brant, Irving. James Madison and American Nationalism. (1968), short survey with primary sources

- Elkins, Stanley M.; McKitrick, Eric. The Age of Federalism (Oxford Univ. Press, 1995); 925pp. most detailed analysis of the politics of the 1790s. online edition

- Gabrielson, Teena, “James Madison’s Psychology of Public Opinion,” Political Research Quarterly, 62 (Sept. 2009), 431–44.

- Kasper, Eric T. To Secure the Liberty of the People: James Madison's Bill of Rights and the Supreme Court's Interpretation (Northern Illinois University Press, 2010) online review

- Kernell, Samuel, ed. James Madison: the Theory and Practice of Republican Government (Stanford U. Press, 2003).

- Kester, Scott J. The Haunted Philosophe: James Madison, Republicanism, and Slavery (Lexington Books, 2008) 132 pp. isbn 978-0-7391-2174-0

- Labunski, Richard. James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights (Oxford U. P., 2006).

- Matthews, Richard K. If Men Were Angels : James Madison and the Heartless Empire of Reason (U. Press of Kansas, 1995).

- McCoy, Drew R. The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (W.W. Norton, 1980). mostly economic issues.

- McCoy, Drew R. The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989). JM after 1816.

- Muñoz, Vincent Phillip. "James Madison's Principle of Religious Liberty," American Political Science Review 97,1(2003), 17–32. SSRN 512922 in JSTOR

- Read, James H. Power versus Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson and Jefferson (University Press of Virginia, 2000).

- Riemer, Neal. "The Republicanism of James Madison," Political Science Quarterly, 69,1(1954), 45–64 in JSTOR

- Riemer, Neal. James Madison: Creating the American Constitution (Congressional Quarterly, 1986).

- Rosen, Gary. American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding (University Press of Kansas, 1999).

- Rutland, Robert A. The Presidency of James Madison (Univ. Press of Kansas, 1990). scholarly overview of his two terms.

- Scarberry, Mark S. "John Leland and James Madison: Religious Influence on the Ratification of the Constitution and on the Proposal of the Bill of Rights," Penn State Law Review, Vol. 113, No. 3 (April 2009), 733-800. SSRN 1262520

- Sheehan, Colleen A. "The Politics of Public Opinion: James Madison's 'Notes on Government'," William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. v49 #3 (1992), 609–627. in JSTOR

- Sheehan, Colleen. "Madison and the French Enlightenment," William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. v59#4 (Oct. 2002), 925–956. in JSTOR.

- Sheehan, Colleen. "Madison v. Hamilton: The Battle Over Republicanism and the Role of Public Opinion," American Political Science Review 98,3(2004), 405–424. in JSTOR

- Sheehan, Colleen."Madison Avenues," Claremont Review of Books (Spring 2004), online.

- Sheehan, Colleen."Public Opinion and the Formation of Civic Character in Madison's Republican Theory," Review of Politics 67,1(Winter 2005), 37–48. in JSTOR

- Sorenson, Leonard R. Madison on the "General Welfare" of America: His Consistent Constitutional Vision (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1995).

- Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the 'Malcontents': The Political Origins of the War of 1812," William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. 33,4(Oct. 1976), 557–585. in JSTOR

- Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the Coercion of Great Britain: Canada, the West Indies, and the War of 1812," in William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. 38,1(Jan. 1981), 3–34. in JSTOR

- Stagg, John C. A. Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American republic, 1783–1830 (Princeton, 1983).

- Stagg, John C. A. Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish-American Frontier, 1776-1821 (2009)

- Vile, John R. William D. Pederson, Frank J. Williams, eds. James Madison: Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman (Ohio University Press, 2008) 302 pp. ISBN 978-0-8214-1832-1 online review

- Wood, Gordon S. "Is There a 'James Madison Problem'?" in Wood, Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different (Penguin Press, 2006a), 141–72.

- Wood, Gordon S. "Without Him, No Bill of Rights: James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights by Richard Labunski", The New York Review of Books (November 30, 2006b). online

Primary sources

- Madison, James (1865). Letters & Other Writings Of James Madison Fourth President Of The United States (called the Congress edition ed.). J.B. Lippincott & Co. http://books.google.com/?id=pb2s8DG_2WUC&pg=RA1-PR11&lpg=RA1-PR11&dq=Letters+%26+Other+Writings+Of+James+Madison+Fourth+President.

- Madison, James (1900–1910). Gaillard Hunt, ed.. ed. The Writings of James Madison. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. http://books.google.com/?id=ri4fEe_y99kC&lpg=RA3-PR21&dq=Writings+of+James+Madison:+comprising+his+public+papers.

- Madison, James (1962). William T. Hutchinson et al., eds.. ed. The Papers of James Madison (30 volumes published and more planned ed.). Univ. of Chicago Press. http://www.virginia.edu/pjm/description1.htm.

- Madison, James (1982). Jacob E. Cooke, ed.. ed. The Federalist. Wesleyan Univ. Press. ISBN 0819560774.

- Madison, James (1987). Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393304051.

- Madison, James (1995). Marvin Myers, ed.. ed. Mind of the Founder: Sources of the Political Thought of James Madison. Univ. Press of New England. ISBN 0874512018.

- Madison, James (1995). James M. Smith, ed.. ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776–1826. W.W. Norton. ISBN 039303691X.

- Madison, James (1999). Jack N. Rakove ed.. ed. James Madison, Writings. Library of America. ISBN 1883011663.

External links

- James Madison: A Resource Guide at the Library of Congress

- The James Madison Papers, 1723–1836 at the Library of Congress

- James Madison: Philosopher and Practitioner of Liberal Democracy, symposium at the Library of Congress

- James Madison at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- James Madison at Find a Grave

- James Madison at the White House

- American President: James Madison (1751–1836) at the Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia

- James Madison at the Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Fund

- Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785) at the Religious Movements Homepage Project, University of Virginia

- The Papers of James Madison at the Avalon Project

- James Madison Museum, Orange, Virginia

- Montpelier, home of James Madison

- "Memories of Montpelier: Home of James and Dolley Madison", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- James Madison at American Presidents: Life Portraits, C-SPAN

- Will, George F. (23 January 2008). "Alumni who changed America, and the world: #1 - James Madison 1771". Princeton Alumni Weekly. http://paw.princeton.edu/issues/2008/01/23/pages/4557/index.xml.

- Works by James Madison at Project Gutenberg

Offices and distinctions United States House of Representatives New constituency Member of the House of Representatives

from Virginia's 5th congressional district

1789–1793Succeeded by

George HancockMember of the House of Representatives

from Virginia's 15th congressional district

1793–1797Succeeded by

John DawsonPolitical offices Preceded by

John MarshallUnited States Secretary of State

1801–1809Succeeded by

Robert SmithPreceded by

Thomas JeffersonPresident of the United States

1809–1817Succeeded by

James MonroeParty political offices Preceded by

Thomas JeffersonDemocratic-Republican nominee for President of the United States

1808, 1812Succeeded by

James MonroeHonorary titles Preceded by

John AdamsOldest living President of the United States

1826–1836Succeeded by

Andrew JacksonCategories:- Madison administration cabinet members

- United States Secretaries of State

- 1751 births

- 1836 deaths

- 18th-century American Episcopalians

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- American people of English descent

- American people of the War of 1812

- American planters

- Continental Congressmen from Virginia

- Democratic-Republican Party Presidents of the United States

- Federalist Papers

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- James Madison

- Jefferson administration cabinet members

- Madison family

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia

- People from King George County, Virginia

- People from Orange County, Virginia

- People of Virginia in the American Revolution

- Presidents of the United States

- Princeton University alumni

- Signers of the United States Constitution

- United States presidential candidates, 1808

- United States presidential candidates, 1812

- University of Virginia

- Virginia colonial people

- Virginia Democratic-Republicans

- People of the American Enlightenment

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.