- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17

-

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 Restored MiG-17 in the markings of the Polish Air Force Role Fighter aircraft National origin Soviet Union Manufacturer Mikoyan-Gurevich First flight 14 January 1950 Introduction October 1952 Status Retired Primary users Soviet Air Force

PLA Air Force

Polish Air Force

Vietnam People's Air ForceNumber built 10,603 Developed from Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 Variants PZL-Mielec Lim-6

Shenyang J-5The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 (Russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-17) (NATO reporting name: Fresco) (China:Shenyang J-5) (Poland: PZL-Mielec Lim-6)[1] is a high-subsonic fighter aircraft produced in the USSR from 1952 and operated by numerous air forces in many variants. Most MiG-17 variants cannot carry air-to-air missiles, but shot down many aircraft with its cannons. It is an advanced development of the very similar appearing MiG-15 of the Korean War, and was used as an effective threat against supersonic fighters of the United States in the Vietnam War. It was also briefly known as the "Type 38", by U.S. Air Force designation prior to the development of NATO codes.[2]

Contents

Development

While the MiG-15bis would be destined to introduce swept wings to air combat over Korea, by 1949, the Mikoyan-Gurevich design bureau had already begun work on its replacement, originally the MiG-15bis45, which would fix any problems found with the MiG-15 in combat.[3] The result was one of the most successful transonic fighters introduced before the advent of true supersonic types such as the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-19 and North American F-100 Super Sabre. The design would ultimately still prove effective into the 1960s when pressed into dogfights over Vietnam against supersonic types which were generally flown at subsonic speeds, and not optimized for subsonic maneuvering short-range engagements.

While the MiG-15 used a Mach sensor to deploy airbrakes because it could not safely exceed Mach 0.92, the MiG-17 was designed to be controllable at higher Mach numbers.[4] Early versions which retained the original Soviet copy of the Rolls-Royce Nene VK-1 engine were heavier with equal thrust. Later MiG-17s would be the first Soviet fighter application of an afterburner which offered increased thrust on demand by dumping fuel in the exhaust of the basic engine.

Though the MiG-17 still strongly resembles its forbear, it had an entirely new thinner and more highly swept wing and tailplane for speeds approaching Mach 1. While the F-86 introduced the "all-flying" tailplane which helped controllability near the speed of sound, this would not be adopted on MiGs until the fully supersonic MiG-19.[5] The wing had a "sickle sweep" compound shape with a 45° angle like the US F-100 Super Sabre near the fuselage (and tailplane), and a 42° angle for the outboard part of the wings.[6] The stiffer wing resisted the tendency to bend its wingtips and lose aerodynamic symmetry unexpectedly at high speeds and wing loads.[3]

Other easily visible differences to its predecessor were the three wing-fences on each wing, instead of the MiG-15's two, the addition of a ventral fin and a longer and less tapered rear fuselage that added about 3 feet in length. The MiG-17 shared the same Klimov VK-1 engine and much of the rest of its construction such as the forward fuselage, landing gear and gun installation was carried over.[6] The first prototype, designated I-330 "SI" by the construction bureau, was flown on the 14 January 1950, piloted by Ivan Ivashchenko.

In the midst of testing, pilot Ivashchenko was killed when his plane developed flutter which tore off his horizontal tail, causing a spin and crash on 17 March 1950. Lack of wing stiffness also resulted in aileron reversal which was discovered and fixed.[7] Construction and tests of additional prototypes "SI-2" and experimental series aircraft "SI-02" and "SI-01" in 1951, were generally successful. On 1 September 1951, the aircraft was accepted for production, and formally given its own MiG-17 designation after so many changes from the original MiG-15. It was estimated that with the same engine as the MiG-15's, the MiG-17's maximum speed is higher by 40–50 km/h, and the fighter has greater manoeuvrability at high altitude.

Serial production started in August 1951, but large quantity production was delayed in favor of producing more MiG-15s so it was never introduced in the Korean War. It did not enter service until October 1952, when the MiG-19 was almost ready to be flight tested. During production, the aircraft was improved and modified several times. The basic MiG-17 was a general-purpose day fighter, armed with three cannons, 1 Nudelman N-37 37mm cannon and two 23mm with 80 rounds per gun, 160 rounds total. It could also act as a fighter-bomber, but its bombload was considered light relative to other aircraft of the time, and it usually carried additional fuel tanks instead of bombs.

Although a canopy which provided clear vision to the rear neccesary for dogfighting like the F-86 was designed, production MiG-17Fs got a cheaper rear-view periscope which would still appear on Soviet fighters as late as the MiG-23. By 1953, pilots got safer ejection seats with protective face curtain and leg restraints like the Martin Baker seats in the west. The MiG-15 had suffered for its lack of a radar gunsight, but in 1951, Soviet engineers obtained a captured F-86 Sabre from Korea and they copied the optical gunsight and SRD-3 gun ranging radar to produce the ASP-4N gunsight and SRC-3 radar. The combination would prove deadly over the skies of Vietnam against aircraft such as the F-4 Phantom whose pilots lamented that guns and radar gunsights had been omitted as obsolescent.[3]

The second prototype variant, "SP-2" (dubbed "Fresco A" by NATO), was an interceptor equipped with a radar. Soon a number of MiG-17P ("Fresco B") all-weather fighters were produced with the Izumrud radar and front air intake modifications.

In early 1953 the MiG-17F day fighter entered production. The "F" indicated it was fitted with the VK-1F engine with an afterburner by modifying the rear fuselage with a new convergent-divergent nozzle and fuel system. The afterburner doubled the rate of climb and greatly improving vertical maneuvers. But while the plane was not designed to be supersonic, skilled pilots could just dash to supersonic speed in a shallow dive, although the aircraft would often pitch up just short of Mach 1. This became the most popular variant of the MiG-17. The next mass-produced variant, MiG-17PF ("Fresco D") incorporated a more powerful Izumrud RP-2 radar, though they were still dependent on Ground Control Interception to find and be directed to targets. In 1956 a small series (47 aircraft) was converted to the MiG-17PM standard (also known as PFU) with four first-generation Kaliningrad K-5 (NATO reporting name AA-1 'Alkali') air-to-air missiles. A small series of MiG-17R reconnaissance aircraft were built with VK-1F engine (after first being tested with the VK-5F engine).

Several thousand MiG-17s were built in the USSR by 1958.

The next development, the MiG-19 was yet another derivative intended to reach supersonic speeds in level flight. The first prototype I-350 was based on the MiG-17 with an even greater wing and tail sweepback of 60 degrees, though the finalized design would look quite different from the original MiG-15.

Design

MiG-17F on display at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California

Day-fighter variants (MiG-17, MiG-17F) were armed with two 23 mm NR-23 cannons (80 rpg) and one 37 mm N-37 cannon (40 rounds), which were mounted on a common bed under the central air intake. The gun bed could be easily wound down for maintenance. On radar-equipped variants (MiG-17P, MiG-17PF), the 37 mm N-37 was replaced with a third 23 mm NR-23 (carrying 100 rpg) to compensate for the weight aft of the radar. All variants could carry 100 kg (220 lb) bombs on two underwing pylons and some could carry 250 kg (551 lb) bombs; however, these pylons were usually used for 400 l (106 US gal) fuel tanks. The MiG-17R was armed with two 23 mm cannons. Most MiG-17s in third world service today fly as ground attack or trainer aircraft.

The only variant with air-to-air missiles was the MiG-17PM (or MiG-17PFU), which could carry four K-5 (NATO: AA-1 "Alkali"). It had no cannons. Some countries occasionally modified their MiG-17s to carry unguided rockets or bombs on additional pylons. MiG-17s in Cuba could be armed with AA-2 "Atoll" missiles.

The MiG-17P was equipped with the Izumrud-1 (RP-1) radar, while the MiG-17PF was initially fitted with the RP-1 which was later replaced with the Izumrud-5 (RP-5) radar. The MiG-17PM was also equipped with a radar, used to aim its missiles. Other variants had no radar.

Licence production

Lim-5 in Polish Air Force markings

Lim-5 in Polish Air Force markings

In 1955, Poland received a license for MiG-17 production. The MiG-17F was produced by the WSK-Mielec factory under the designation Lim-5. The first Lim-5 was built on 28 November 1956 and 477 were built by 1960. An unknown number were built as the Lim-5R reconnaissance variant, fitted with the AFA-39 camera. In 1959–1960, 129 MiG-17PF interceptors were produced as the Lim-5P . PZL-WSK also developed several Polish strike variants based on the MiG-17: the Lim-5M, produced from 1960; Lim-6bis, produced from 1963; and Lim-6M (converted in the 1970s); as well as two reconnaissance variants: the Lim-6R (Lim-6 "bis" R) and MR.

In China, an initial MiG-17F was assembled from parts in 1956, with license production following in 1957 at Shenyang. The Chinese-built version is known as the Shenyang J-5 (for local use) or F-5 (for export). According to some sources, earlier MiG-17s which had been delivered directly from the USSR were designated "J-4". From 1964, the Chinese produced a radar-equipped variant similar to the MiG-17PF, which was known as the J-5A (F-5A). The Chinese also developed a two-seat trainer variant, the JJ-5 (FT-5 for export), which integrated the cabin of the JJ-2 (a license-built MiG-15UTI) with the J-5. It was produced in 1966-1986, being the last-produced MiG-17 variant and its only twin-seater variant. The Soviets did not produce a two-seat MiG-17 as they felt that the training variant of the older MiG-15 was sufficient.

Many Soviet and licence-built examples remain in service to this day, though not all are currently active, making the MiG-17 one of the longest serving fighters ever built.

Operational history

MiG-17s were designed to intercept straight and level flying enemy bombers, not for air to air combat (Dog-fighting) with other fighters.[8] This subsonic (.93 Mach) fighter was effective against slower (.6-.8 Mach), heavily loaded US fighter-bombers, as well as the mainstay American strategic bombers during the MiG-17's development cycle (such as the Boeing B-50 Superfortress or Convair B-36 Peacemaker, which were both still powered by piston engines). Even if the target had sufficient warning and time to shed weight and drag by dropping external ordnance and accelerate to supersonic escape speeds, doing so would have inherently forced the enemy aircraft to abort its bombing mission. However, the USAF's introduction of strategic bombers capable of supersonic dash speeds such as the Convair B-58 Hustler and General Dynamics FB-111 rendered the MiG-17 obsolete in front-line PVO service and they were supplanted by supersonic interceptors such as the MiG-21 and MiG-23.

MiG-17s were not available for the Korean War, but saw combat for the first time over the Straits of Taiwan when PRC (Communist China) MiG-17s clashed with ROC (Nationalist China) Sabres in 1958.

In 1958, MiG-17s downed a US reconnaissance Lockheed C-130 Hercules over Armenia, with 17 casualties.[9]

During the 1960s and 1970s, the MiG-17 would find a new notoriety over the skies of Vietnam as the first of a handful of fighters such as the Hawker Hunter and Harrier which would demonstrate the effectiveness of using subsonic fighters to challenge and destroy supersonic fighters.

Vietnam War

In 1960, the first group of approximately 50 North Vietnamese airmen were transferred to the People's Republic of China (PRC) to begin transitional training onto the MiG-17. By this time the first detachment of Chinese trained MiG-15 pilots had returned to North Vietnam, and a group of 31 airmen were deployed to the People's Liberation Army Air Force base at Son Dong for conversion to the MiG-17. By 1962 the first North Vietnamese pilots had finished their MiG-17 courses in the Soviet Union and Red China, and returned to their units; to mark the occasion, the Soviets sent as a "gift" 36 MiG-17 fighters and MiG-15UTI trainers to Hanoi in February 1964. These airmen would create North Vietnam's first jet fighter regiment, the 921st.[10] By 1965, another group of MiG pilots had returned from training in Krasnodar, in the USSR, as well as from the PRC. This group would form North Vietnam's second fighter unit, the 923rd Fighter Regiment. While the newly created 923rd FR operated strictly MiG-17s, and initially these were the only types available to oppose modern American supersonic jets, more modern supersonic Soviet fighters would be later introduced as the 921st FR would operate both MiG-17s and MiG-21s (in 1969 the 925th FR MiG-19 unit would be formed).[11]

Although US fighter-bombers had been engaged in combat since 1961,[12] and some of the most experienced Americans such as James Robinson Risner were Korean War aces, the North Vietnamese Air Force MiGs and their untried pilots lacked combat experience. The baptism of fire of the MiG-17 in this conflict occurred on 3 April 1965. That day two groups of MiGs took off from Noi Bai airbase. The first group comprised two jets and acted like a bait; the second was made-up of four MiG-17s and was the strike group. Their target were US Navy aircraft supporting an USAF 80-aircraft strike package trying the knock out Ham Rung bridge near Thanh Hoa. The MiG-17 leader, Lt. Pham Ngoc Lan, spotted a group of Vought F-8 Crusaders of the VF-211, USS Hancock, and shot-up the F-8E flown by Lt. Cdr. Spence Thomas, which would perform an emergency landing ashore at Da Nang. His wingman Phan Van Tuc claimed a second F-8, but this is not corroborated by USN loss listings.[13]

On 4 April 1965, the USAF conducted a "re-strike" on the Hàm Rồng/Thanh Hoa bridge with 48 Republic F-105 Thunderchiefs of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) loaded with 384 x 750 lb (340 kg) bombs. The Thunderchiefs were escorted by a MiG CAP flight of North American F-100 Super Sabres from the 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS). Coming from above, four MiG-17s from the 921st Fighter Regiment (FR) tore through the escorts and dove onto the Thunderchiefs, shooting two of them down; the leader Tran Hanh downed F-105D 59-1754 of Major F. E. Benett, and his element leader Le Minh Huan downed F-105D 59-1764 of Captain J. A. Magnusson.[14][15] The Super Sabres engaged with one firing a "AIM-9 Sidewinder" air-to-air missile which apparently missed (or malfunctioned),[16] and another F-100D flown by Captain Donald Kilgus fired 20mm cannons,[17] which also apparently missed, but in fact shot down and killed Tran Hanh's wingman Pham Giay.[18] No other US airmen reported any confirmed aerial kills during the air battle. However, Tran Hanh stated that three of his accompanying MiG-17s had been shot down by the opposing USAF fighters.[19]

During the 4 April 1965 engagement, four MiG-17s from the 921st FR had tangled with over 50 US jet fighter-bombers, consisting of F-105s and F-100s.[16] Three F-100s from the MiGCAP, piloted by LTC Emmett L. Hays, CPT Keith B. Connolly,[16] and CPT Donald W. Kilgus, all from the 416th TFS,[20] engaged the MiG-17s. One Super Sabre fired an air-to-air missile and Connolly and Kilgus engaged with 20 mm cannon, with only Kilgus claiming a probable kill. The four attacking MiGs from the 921st FR were flown by Flight Leader Tran Hanh, Wingman Pham Giay, Le Minh Huan and Tran Nguyen Nam.[21] Flight Leader Tran Hanh was the only survivor from the air battle and reportedly stated that his three MiG-17s were "... shot down by the F-105s."[19] Based upon the report, the USAF F-100s very well could have been mistaken for F-105s, and the reported loss of three MiG-17s to those mistaken jet fighters[14] would indicate that the USAF F-100 Super Sabres had obtained the first US aerial combat victories during the Vietnam War.

The MiG-17 was the primary interceptor of the fledgling Vietnam People's Air Force in 1965, scoring its first aerial victories and seeing extensive combat during the Vietnam War, the aircraft frequently worked in conjunction with MiG-21s and MiG-19s. Many historians believe that some North Vietnamese pilots, in fact, preferred the MiG-17 over the MiG-21 because it was more agile, though not as fast; however, of the 16 NVAF Aces of the war, 13 of them attained that status while flying the MiG-21. Only three North Vietnamese Airmen gained Ace status while flying the MiG-17. Those were: Nguyen Van Bay (7 victories), Luu Huy Chao and Le Hai (both with six).[22]

The MiG-17 was not originally designed to function as a fighter-bomber, but in 1971 Hanoi directed that United States Navy warships were to be attacked by elements of the North Vietnamese Air Force. This would require the MiG-17 to be fitted with bomb mountings and release mechanisms. Chief Engineer of the NVAF ground crews, Truong Khanh Chau,[23] was tasked with the mission of modifying two MiG-17s for the ground attack role; after three months of work, the two jets were ready. On 19 April 1972, two pilots from the 923rd FR took their bomb laden MiG-17s and attacked the US Navy destroyer USS Higbee (DD-806) and light cruiser USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5). Each MiG was armed with two 250 kg (550 lb) bombs. Pilot Le Xuan Di managed to hit the destroyer's aft 5" gun mount, destroying it, but inflicting no fatalities, as the crewmen had vacated the turret earlier due to a malfunction with the gun system.[24] The other attacker from the two-plane sortie was flown by Nguyen Van Bay, an airman who would later end the war with seven confirmed air victories, all accomplished with his MiG-17. On this day however, his fighter either managed to slightly damage the USS Oklahoma City, or miss it entirely, depending upon the source. Each pilot had completed their drop of two bombs each and returned to base. After the war, Truong Khanh Chau became the director of the Vietnam Institute for Science and Technology in 1977.

From 1965 to 1972, MiG-17s from the NVAF 921st and 923rd FRs would claim 71 aerial victories against US aircraft: 11 Crusaders, 16 F-105 Thunderchiefs, 32 McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom IIs, two Douglas A-4 Skyhawks, seven Douglas A-1 Skyraiders (propeller driven strike aircraft), one C-47 cargo/transport aircraft, one Sikorsky CH-3C helicopter and one Ryan Firebee UAV.[25]

The American fighter community was shocked in 1965 when elderly, subsonic MiG-17s downed sophisticated Mach-2-class F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers over North Vietnam. To redress disappointing combat performance against smaller, more agile fighters like the MiGs, the Americans established dissimilar air combat training (DACT) in training programs such as "TOPGUN", which employed subsonic Douglas A-4 Skyhawk aircraft to mimic more manoeuvrable opponents such as the MiG-17. The US Navy also set Adversary squadrons equipped with the nimble A-4 at each of its fighter and attack Master jet bases to provide DACT.

Other MiG-17 users

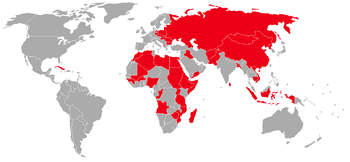

Twenty countries flew MiG-17s. The MiG-17 became a standard fighter in all Warsaw Pact countries in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They were also bought by many other countries, mainly in Africa and Asia, that were neutrally aligned or allied with the USSR. The MiG-17 still flies today in the air forces of Burkina Faso, China (JJ-5 Trainer) Mali, Mozambique, North Korea, Pakistan (JJ-5 Trainer), Republic of the Congo, Somaliland, Sudan, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

According to the FAA there are 27 privately owned MIG-17s in the U.S.[26]

Middle East

MiG-17s were sold and/or imported to many Middle Eastern countries and saw action in nearly all of the Arab-Israeli conflicts starting when 12 of them served with the Egyptian Air Force during the Suez Crisis of 1956, plus hundreds more served, and were mostly destroyed, in the Egyptian and Syrian Air Forces during the Six-Day War of 1967 as well as the War of Attrition, the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and the 1982 Israeli Invasion of Lebanon.[citation needed]

Africa

At least 24 of them served with the Nigerian Air Force and were flown by a mixed group of local Nigerian and mercenary pilots from East Germany, Soviet Union, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and Australia during the 1967-70 Nigerian Civil War.

Asia

Four were hurriedly supplied by the USSR to Sri Lanka during the 1971 insurgency and were used for bombing and ground attack in the brief insurgency. Four North Korean MiG-17 aircraft were involved in the EC-121 shootdown incident, where they managed to shoot down an American EC-121 Warning Star.

Soviet Union

Similarly in 1958, a US Air Force Lockheed C-130 was shot down by four MiG-17 fighters when it flew into Soviet airspace near Yerevan, Armenia while on a Sun Valley SIGINT mission, with all 17 crew killed.

United States

A number of U.S. federal agencies undertook a program at Groom Lake to evaluate the MiG-17 to help fight the Vietnam War, as North Vietnamese MiG-17s and MiG-21s had a kill rate against them of 9:1. The program was code-named HAVE DRILL, involving trials of two ex-Syrian MiG-17F Frescos over the skies of Groom Lake. These aircraft were given USAF designations and fake serial numbers so that they may be identified in DOD standard flight logs

In addition to tracking the dog fights staged between the various MiG models against virtually every fighter in U.S. service, and against SAC's B-52 Stratofortress and B-58 Hustlers to test the ability of the bombers’ countermeasures systems. They also performed radar cross-section and propulsion tests that contributed greatly to improvements in U.S. aerial performance in Vietnam.

Variants

- I-300

- Prototype.

- MiG-17 ("Fresco A")

- Basic fighter version powered by VK-1 engine ("aircraft SI").

- MiG-17A

- Fighter version powered by VK-1A engine with longer lifespan.

- MiG-17AS

- Multirole conversion, fitted to carry unguided rockets and the K-13 air to air missile.

- MiG-17P ("Fresco B")

- All-weather fighter version equipped with Izumrud radar ("aircraft SP").

- MiG-17F ("Fresco C")

- Basic fighter version powered by VK-1F engine with afterburner ("aircraft SF").

- MiG-17PF ("Fresco D")

- All-weather fighter version equipped with Izumrud radar and VK-1F engine ("aircraft SP-7F").

- MiG-17PM/PFU ("Fresco E")

- Fighter version equipped with radar and K-5 (NATO: AA-1 "Alkali") air-to-air missiles ("aircraft SP-9").

- MiG-17R

- Reconnaissance aircraft with VK-1F engine and camera ("aircraft SR-2s")

- MiG-17SN

- Experimental variant with twin side intakes, no central intake, and nose redesigned to allow 23 mm cannons to pivot to engage ground targets. Not produced.

- Shenyang J-5

Some withdrawn aircraft were converted to remotely controlled targets.

Operators

Afghanistan

Afghanistan- Afghan Air Force. Around 100 MiG-17F acquired by the Afghan Air Force from 1957.

Albania

Albania- Albanian Air Force - 20 aircraft, including 8 Chinese-made JJ-5 trainers, were acquired. All Albanian fighters are in storage, retired from active service, due to lack of spare parts

Algeria

Algeria- Algerian Air Force

Angola

Angola- People's Air and Air Defence Force of Angola.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh- Bangladeshi Air Force

Bulgaria

Bulgaria- Bulgarian Air Force

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Cambodia

Cambodia- Royal Cambodian Air Force - 16 aircraft, including five MiG-17s and 11 Shenyang J-5 were received from the Soviet Union and China in 1967-1968, later all were destroyed on the ground in 1971.[27]

China

China- see also Shenyang J-5

- People's Liberation Army Air Force

- People's Liberation Army Navy Air Force. J-5 trainers still in limited service. Single seat fighters have been retired and sold to other countries.

Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo- Congolese Air Force

Cuba

Cuba- Cuban Air Force

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia- Czechoslovakian Air Force - two MiG-17F for evaluation purposes (EP-01 and EP-02), 34 MiG-17PF all-weather interceptors. All retired before 1970.

East Germany

East Germany- East German Air Force

Egypt

Egypt- Egyptian Air Force

Ethiopia

Ethiopia- Ethiopian Air Force. All retired.

Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Indonesia

Indonesia- Indonesian Air Force - Using MiG-17F and MiG-17PF. All of the aircraft acquired in 1961. Used during the preparation of Operation TRIKORA in 1962 to take Western New Guinea, now Papua and Papua Barat, from the Netherlands. Some of the aircraft were used intensively in Air Forces / TNI-AU Acrobatic Team in 1962 for air show events around Indonesia. All aircraft were grounded in 1969. None have been in service since 1970.

Iraq

Iraq- Iraqi Air Force

Hungary

Hungary- Hungarian Air Force

Libya

Libya- Libyan Air Force

Madagascar

Madagascar Mali

Mali- MiG-17 in service.

Mongolia

Mongolia- Mongolian Air Force - Between in 1970-1977 received than 17 aircraft

Morocco

Morocco- Royal Moroccan Air Force

Mozambique

Mozambique- MiG-17 in service.

Nigeria

Nigeria- Nigerian Air Force

North Korea

North Korea- North Korean Air Force - J-5 still in service.

Pakistan

Pakistan- Pakistan Air Force JJ-5 Trainer in service.

Poland

Poland

Romania

Romania- Romanian Air Force - 12 MiG-17PF and 12 MiG-17F entered service in 1955 and 1956, respectively.

Somalia

Somalia- Somali Air Corps

Soviet Union

Soviet Union

- Soviet Air Force

- Soviet Naval Aviation

- Soviet Anti-Air Defence

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka- Sri Lankan Air Force - All retired from service.

Syria

Syria- Syrian Air Force

Tanzania

Tanzania- Tanzanian Air Force - J-5 in service.

Uganda

Uganda- Ugandan Air Force

Vietnam

Vietnam- Vietnam People's Air Force

Yemen

Yemen- Yemen Air Force

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe- Air Force of Zimbabwe JJ-5 Trainer in service.

Specifications (MiG-17F)

Blueprints:[1]

Data from Combat Aircraft since 1945,[28]MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design[29]

General characteristics

- Crew: One

- Length: 11.26 m (36 ft 11½ in)

- Wingspan: 9.63 m (31 ft 7 in)

- Height: 3.80 m (12 ft 5½ in)

- Wing area: 22.6 m² (243.3 ft²)

- Empty weight: 3,919 kg[30] (8,640 lb)

- Loaded weight: 5,350 kg (11,770 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 6,069 kg (13,375 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Klimov VK-1F afterburning turbojet

- Dry thrust: 22.5 kN (5,046 lbf)

- Thrust with afterburner: 33.8 kN (7,423 lbf)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,145 km/h (618 knots, 711 mph) at 3,000 m (10,000 ft)

- Range: 2,020 km (1,091 nmi, 1,255 mi) with drop tanks

- Service ceiling: 16,600 m (54,450 ft)

- Rate of climb: 65 m/s (12,800 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 237 kg/m² (48 lb/ft²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.63

Armament

- 1x 37 mm Nudelman N-37 cannon (40 rounds total)

- 2x 23 mm Nudelman-Rikhter NR-23 cannons (80 rounds per gun, 160 rounds total)

- Up to 500 kg (1,100 lb) of external stores on two pylons, including 100 kg (220 lb) and 250 kg (550 lb) bombs, unguided rockets or external fuel tanks.

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

- List of military aircraft of the Soviet Union and the CIS

- List of fighter aircraft

References

- Notes

- ^ Parsch, Andreas and Aleksey V. Martynov. "Designations of Soviet and Russian Military Aircraft and Missiles."Non-U.S. Military Aircraft and Missile Designations, revised 18 January 2008. Retrieved: 30 March 2009.

- ^ Parsch, Andreas and Aleksey V. Martynov. "Designations of Soviet and Russian Military Aircraft and Missiles: 5.1 "Type" Numbers (1947-1955)." Non-U.S. Military Aircraft and Missile Designations, revised 18 January 2008. Retrieved: 30 March 2009.

- ^ a b c USN F-4 Phantom II Vs VPAF MiG-17: Vietnam 1965-72 By Peter Davies

- ^ Sweetman 1984, p. 11.

- ^ HobbyBoss 1/48 MiG-17F

- ^ a b Crosby 2002, p. 212.

- ^ OKB MIG-17

- ^ Michel 2007, p. 79.

- ^ "The Shootdown of Flight 60528." National Vigilance Park- NSA/CSS via nsa.gov, 12 January 2009. Retrieved: 11 March 2011.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 13, 58.

- ^ Anderton 1987, p. 57.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b Toperczer 2001, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Zampini, Diego. "Víboras Mortales" (Deadly Snakes) (in Spanish). Defensa. Nº 345, January 2007, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b c Anderton 1987, p. 71.

- ^ Olynyk 1999, p. 55.

- ^ Zampini 2007, p. 59.

- ^ a b Toperczer 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Davies 2003, pp. 87, 88.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 85, 86.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 54, 55.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 88, 89, 90.

- ^ http://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/AcftRef_Inquiry.aspx

- ^ Conboy 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Belyakov and Marmain 1994, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Gunston 1995, p. 193.

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/russia/mig-17-specs.htm

- ^ http://www.vectorsite.net/avmig15_2.html

- Bibliography

- Anderton, David A. North American F-100 Super Sabre. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1987. ISBN 0-85045-622-2.

- Belyakov, R.A. and J. Marmain. MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1-85310-488-4.

- Butowski, Piotr (with Jay Miller). OKB MiG: A History of the Design Bureau and its Aircraft. Leicester, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1991. ISBN 0-904597-80-6.

- Conboy, Kenneth. The War in Cambodia 1970-75(Men-at-Arms series 209). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 1989. ISBN 0-85045-851-X.

- Crosby, Francis. Fighter Aircraft. London: Lorenz Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7548-0990-0.

- Davies, Peter E. North American F-100 Super Sabre. Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 1-861265-778.

- Gunston, Bill. The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft 1875–1995. London: Osprey, 1995. ISBN 1-85532-405-9.

- Koenig, William and Peter Scofield. Soviet Military Power. Greenwich, Connecticut: Bison Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86124-127-4.

- Michel III, Marshall L. Clashes: Air Combat Over North Vietnam 1965-1972. Annapolis, Maryland, USA: Naval Institute Press, 1997, 2007. ISBN 1-59114-519-8.

- Olynyk, Dr. Frank. US Post World War 2 Victory Credits. Self-published, 1999.

- Robinson, Anthony. Soviet Air Power. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-180-0.

- Sweetman, Bill. Modern Fighting Aircraft: Volume 9: MiGs. New York: Arco Publishing, 1984. ISBN 978-0668064934.

- Sweetman, Bill and Bill Gunston. Soviet Air Power: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Warsaw Pact Air Forces Today. London: Salamander Books, 1978. ISBN 0-51724-948-0.

- Toperczer, Istvan. MiG-17 and MiG-19 Units of the Vietnam War (Osprey Combat Aircraft: 25). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-162-1.

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-875671-50-1.

External links

- MiG-17 FRESCO from Global Security.org

- MiG-17 Fresco from Global Aircraft

- MiG-17 Fresco from Danshistory.com

- Cuban MiG-17

- MiG 17: Home of a True Fighter

- Warbird Alley's MiG-17 Page

- Mig Alley USA, Aviation Classics, Ltd Reno, NV

- Lethal Snakes - Russian viewpoint Mig-17 tactics

Mikoyan and Gurevich (MiG) aircraft Fighters/Interceptors Attack Reconnaissance Trainers Experimental Lists relating to aviation General Aircraft (manufacturers) · Aircraft engines (manufacturers) · Airlines (defunct) · Airports · Civil authorities · Museums · Registration prefixes · Rotorcraft (manufacturers) · TimelineMilitary Accidents/incidents Records Categories:- Mikoyan aircraft

- Soviet fighter aircraft 1950–1959

- Military aircraft of the Vietnam War

- 1952 introductions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.